The recovery of Ireland's historic past was a project undertaken by numerous scholars and artists from the mid-eighteenth century onwards, recording traditional poetry and music as well as antiquities, both pagan and Christian. With respect to these last, it was not until the nineteenth century that sustained fieldwork and scholarship began to put that material history on firm foundations. These researches were widely regarded as restoring its rightful dignity to Irish history, and they resonated with those supporters of Irish nationalism, such as Thomas Davis (1814-45) who, in the pages of The Nation, recommended Irish antiquities and historical subjects to Irish painters (Literary and Historical Essays 153-172). Irish antiquarian scholarship at mid-century was prosecuted with the same rigor as its equivalents elsewhere and was not overtly politicized, but it came to fruition in a highly volatile situation. This essay is not intended to situate that scholarship in a political climacteric, or at least not to do so directly. Instead it pays attention to an approach that seeks to be as disinterested as possible, providing (visual) information of unimpeachable objectivity.

In the preface to his Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland (1845), the Irish artist and antiquarian George Petrie introduced his readers to its illustrations in the following terms: ‘It will be seen that they make but slight pretensions to the character of works of art. Where no fine writing was attempted, showy illustrations, got up with a view to popular effect, and leading to an almost necessary sacrifice of truthfulness, would be very little in harmony. For their accuracy, however, I can fearlessly pledge myself. This has been the point attended to above all others, and of which the absence of all affectation of freedom of handling, or forcible effect, will give abundant evidence. They may be considered as quotations from our ancient monuments, made with the same anxious desire for rigid accuracy, as those supplied from literary and other sources in the text; and though slighter or more attractive sketches might have sufficiently answered my purpose, they would not have been sufficient to gratify my desire to preserve trustworthy memorials of monuments now rapidly passing away. (Petrie ix-x)’ Petrie's endorsement offers an opportunity for further reflection, for the declaration it makes about the purpose of illustration in archaeological surveys is not only historically specific, revealing something about the assumptions current in antiquarian circles in the nineteenth century. It can also prompt us to think more widely about the nature of archaeological illustration in its various modes.

Although Petrie is discussed in what follows as an exemplar of a wider tendency, some rehearsal of his professional life will help to situate his remarks in their historical context. Born in 1790, the son of a Scottish portrait painter recently settled in Dublin, Petrie trained initially as an artist and secured his early reputation by providing landscape sketches for engaving in topographical works, notably Thomas Cromwell's Excursions through Ireland (1820) and James Norris Brewer's Beauties of Ireland (1825). As a painter in watercolor he exhibited regularly at the Royal Hibernian Academy and was one of the key artists who developed the idea of the Romantic landscape in Ireland from the 1830s to the 1850s. It is not known precisely when Petrie's scholarly interest in antiquities began, but from the 1820s he was actively concerned with early Irish history and was an important contributor to the activities of the Royal Irish Academy, the learned society founded in 1785 to promote Irish historical, scientific, and literary studies. The Royal Irish Academy was also the repository of the national collection of antiquities, whose study was an important prerequisite for the scholarly reassessment of Irish cultural achievement, and Petrie was instrumental in the acquisition of highly important early manuscripts and metalwork for the collection. From 1833 to 1844 he was head of the Topographical Department of the Irish Ordnance Survey, charged with recording Irish antiquities, and he also edited two popular antiquarian magazines, the Dublin Penny Journal (1832-36) and the Irish Penny Journal (1840-41). His important contributions to the collection of traditional Irish music were published as The Ancient Music of Ireland (1855). Petrie's scholarship set high standards for the prosecution of historical and antiquarian research, and he has justly been called the father of Irish archaeology. His essay “On the Origin and Uses of the Round Towers of Ireland” (1833) was awarded the gold medal and a £50 prize from the Royal Irish Academy. It was regarded as ground-breaking and won a bigger audience when republished in The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland.

The fact that Petrie and many of his contemporaries turned to woodcut engravings is significant, for the mid-nineteenth century was the heyday of the woodcut print whose technique facilitated the production of large illustrated surveys. In comparison with engravings on steel, woodcuts took relatively little time to make, and because they used a relief process they could be placed in the press among the type, rather than needing to be printed separately, as was the case with intaglio prints. This allowed publishers to incorporate illustrations quite cheaply and so run less of a commercial risk than was the case with engravings. It also meant that many more illustrations could be supplied; the Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland, with 256 of them, obviously benefitted from that circumstance.

Petrie's illustrator, George A. Hanlon, had the task of taking Petrie's field sketches and rendering them as woodcut engravings without any sacrifice of the accuracy Petrie had invested in them. Hanlon's life and career are not as well documented as Petrie's. He was born circa 1814 and was a student in the Royal Dublin Society's Drawing School in 1830. He provided woodcut illustrations for a variety of topographical, antiquarian, scientific, and literary works in the 1840s and 1850s, including William Wilde's The Beauties of the Boyne (1849), William Wakeman's Archæologia Hibernica (1848) and William Wilde's Descriptive Catalogue of the Antiquities ... in the Museum of the Royal Irish Academy (1857). He won prizes awarded by the Royal Irish Art Union for wood engraving in 1844 (for architectural views after Petrie) and again in 1846. His work with antiquities seems to have been the mainstay of his career in Ireland and the 1849-50 audit of the Royal Irish Academy records payments to him of £41 "on account of woodcuts."

Hanlon achieved intellectual acknowledgement of his contribution to historical research, for by 1854 he had become a member of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society (Proceedings and Transactions 8).

In Petrie's words (quoted above), Hanlon had engraved the designs "with an anxious fidelity" and Thomas Davis' review of the Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland was full of praise for his efforts: "The work is crowded with illustrations drawn with wonderful accuracy, and engraved in a style which proves that Mr. O'Hanlon [sic], the engraver, has become so proficient as hardly to have a superior in wood-cutting" (Round Towers 107). These encomia do not, however, allow the modern reader to apprehend precisely what it is that Hanlon's images convey. Contemporary wood engravers could produce images of considerable refinement and complexity, as seen for example in the work issuing from Josiah Whymper's establishment in London, but for the most part Hanlon's images are shorn of all that virtuosity of line and tone. Only the handful of them that adopt a topographical procedure begin to approach it; the majority of them are deliberately prosaic. Now Petrie's text advances a view on Hanlon's illustration which bears on all this. As we have seen, he declares that "they make but slight pretensions to the character of works of art." They are not "showy," they have no "affectation of freedom of handling, or forcible effect," and they are not especially attractive; instead, they are "accurate", "trustworthy" and "may be considered as quotations". This last statement is the nub of it, for Petrie makes a claim here that puts forward the possibility of an unmediated image, as true to its original as a selection of text copied from a manuscript.

The analogy is, however, a loose one. Accurate quotation from a text is possible because the only thing that might impede it would be physical damage to the original source, serious enough to make a word or letter impossible to decipher with confidence. Once damage is ruled out, it is of little consequence to the reader's understanding how the quotation is presented on the page. As long as it is legible, it doesn't matter that handwriting has become type or that one typeface or font has been substituted for another; when it comes to the transmission of a string of words, the choice of communicative vehicle is irrelevant. This is not, of course, to ignore the fact that the practice of editorial work may raise further questions about the corruption of the text, nor does it imply that it is possible simply though inspection to determine the meaning of a textual fragment, but it is to point out that the syntactic organization of a text is not affected by its being rendered in another script. With visual representation, however, the choice is crucial. Illustration is always and inevitably an act of interpretation where every decision about technique and materials acts as a form of editorial redaction that inevitably compromises the possibility of quotation.

If antiquarian representation as quotation is a problematic concept, it may perhaps be better illuminated with reference to the three cardinal distinctions drawn in Charles Sanders Peirce's semiotic system: index (where the signifier is directly connected to the signified), icon (where the signifier resembles the signified), and symbol (where the signifier's connection to what is signified is arbitrary or conventional). Peirce is clear that his definitions of semiosis refer to "modes of relationship" between sign vehicles (words, images, etc.) on the one hand and their referents on the other and that these modes are not mutually exclusive; signification may involve a combination of all these different forms of semiotic register. Using his definitions, antiquarian illustration can be classified for the most part as predominantly iconic, but it is often, despite the illustrator's best efforts, tilted towards the symbolic. And this is so by virtue of the modes of depiction that all archaeological illustrations deploy. The recognition of the coded nature of archaeological illustration has long been understood. It can be found, for example, in remarks made by Stuart Piggott, who took a cue from Ernst Gombrich to write about the symbolic nature of visual communication in archaeology, "the agreed code of conventions" employed by its illustrators that is informative only to those trained in its use (Piggott 165).

Piggott's concern was primarily with the visual language of professional archaeology, but as a scholar of archaeological draftsmanship of the previous three hundred years he was aware that all forms of representation are artificial, even if the coding is so taken for granted that we cease to pay attention to it. Hanlon and his fellow nineteenth-century illustrators were necessarily bound by arbitrary and conventional modes of signification.

Petrie's notion of an illustration that can be classed as a quotation can be usefully investigated from Peirce's perspective. Before the advent of photography, the only representation that came close to working strictly in the sense Petrie claims was a cast or mold, which in Peirce's semiotic system would be classed as an indexical sign (where the signifier is directly connected to the signified). Needless to say, a cast that bids to offer a simulacrum of the original has to be colored and accurate coloration, if attempted at all, raises a whole new set of historical and technical problems; but in terms of its size and its textural, formal, and iconographical data, a cast is normally as reliable as any "quotation", in the sense Petrie intended. As an example, we might consider the plaster cast of part of the Bayeux tapestry taken by Charles Alfred Stothard in 1816-17 and hand-colored by him. The cast supplemented Stothard's work at Bayeux for the Society of Antiquaries and probably helped him refine his visual record of the tapestry, which resulted in two engravings. Both of them were engraved by James Basire, Jr. The first was derived from Stothard's initial survey of the tapestry. Stothard took this back to Bayeux and colored it on the spot. The second, published in Vetusta Monumenta (1819-22), shows a more exact rendering of the appearance of the tapestry, including details such as the stitching and variations in the disposition and color of the script.

Casts or molds of carved stone constitute a comparable case. The idea of taking casts to reproduce sculpture is first recorded in 1540, when the artists Francesco Primaticcio and Jacopo Vignola made molds of Roman sculpture and took them back to France to be cast in bronze for François I at Fontainebleau (MacGregor 76, 89). Thereafter, the taking of casts from sculpture spread widely throughout Europe. Cast collections initially comprised copies of classical sculpture and, from the eighteenth century, some of them included copies of Renaissance works as well. From at least the 1830s, a few examples of medieval sculpture were added to some cast collections, as with that of the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. As their remit widened, cast collections brought together simulations of sculpture and architecture in a panorama of human achievement. A good example is the Architectural Museum, established in London in 1851 by the architect George Gilbert Scott and his associates. Its cast collection was designed to become the core of a national museum of architecture (Bottoms 115-139). The Fine Arts courts on display at the Crystal Palace from the mid-1850s were much more ambitious, displaying casts and architectural ensembles from ancient Egypt to the present.

The most long-lived such collection was the South Kensington Museum's Architectural Courts which opened in October 1873 (Bilbey 182-185).

As the Crystal Palace example shows, the taking of casts from Irish monuments was coeval with these developments.

The pioneer for this kind of reproduction was Henry O'Neill who exhibited casts of High Crosses at the Dublin International Industrial Exhibition in 1853 (Sproule). His example was followed by Colonel G.T. Plunkett, Director of the Dublin Museum of Science and Art, who commissioned the cast reproduction of a number of Irish artifacts, including carvings from Newgrange and a number of High Crosses, between 1898 and 1907.

The antiquary John Westwood took advantage of O'Neill's work to make rubbings from the casts on display and used the information so derived to amend J. D. Chambers' recent (1848) account of the iconography of the smaller Monasterboice cross.

Here then we have a case where the transmission from original to copy was so accurate as to allow new hypotheses to be advanced. In a letter he sent to the Royal Irish Academy in 1854 Westwood recommended that rubbings be taken of all Ireland's carved and inscribed monuments, to form a record of them before they were further damaged or destroyed, citing the example of the Reverend Charles Graves' rubbings from ogham stones.

In Peircean terms a rubbing, like a mold, is also indexical, for the representation is produced by direct contact with its subject and traces what lies beneath the paper, but unlike a mold it cannot so easily be considered a "quotation." It shares the mold's limitation of translating one medium into another and likewise its inability to copy color automatically but, more damagingly, it makes a two-dimensional image of a three-dimensional object and uses graphic marks to render a sculpted surface. But the rubbing is a good limit case to begin the exploration of modes in the imaging process. What a rubbing produces is an edited image, where the original object has been purged of all that is not essential to its apprehension. Or, rather, the rubbing hypostatizes our cognitive approach to the object, our intellectual as opposed to our sensual apprehension of it.

Effectively, the rubbing process distills from the monument a representation that is rich in information and treats as unnecessary distractions the visual and material qualities that suffuse the original. And this process of distillation is always present in antiquarian illustration, too. The antiquarian image, in other words, is best understood as a crystallization of cognitive assumptions about the object. But these assumptions are not uniform, and decisions made about where an object's significance lies—what aspect of it is most revealing and therefore requires visual capturing—may contain a number of motives. The illustrator's choice of medium, technique, and presentation is likewise a mode of signification; the same object becomes transmuted under the impress of its different treatments. The question that arises from this is the extent to which the illustration resembles the object under scrutiny and what, in this context, we should take "resemble" to mean. For example, we readily accept two-dimensional and scaled presentations of three-dimensional objects. Likewise, we accept that an illustration is not necessarily required to provide a facsimile presentation of all surface details. In these and related cases, the question of resemblance is settled by the discursive context which controls the production and consumption of the image. Depending on that context, the same feature may constitute significant evidence or be an adventitious distraction from the object's correct presentation. It follows that if both motive and method affect the process of producing the image, it is certainly arguable that our designation of an illustration as faithfully resembling its original is as much a judgment about the illustrator's understanding of the conventions of visual recording in the specific circumstances of making the image as it is a judgment about accuracy in an absolute sense. Resemble, with its connotations of mediation, should not be confused with replicate.

In Peirce's system, because illustrations resemble their originals they are iconic even when their pictorial language is highly conventional (Harthshorne, Weiss, and Burke 279). Nevertheless, the question we need to ask is, what balance is struck between index, icon, and symbol in antiquarian illustration? As already indicated, the antiquarian image is often more symbolic than we might think and operates diagrammatically, for the adoption of an agreed or conventional usage pushes the illustration, no matter how naturalistic it appears, into the realm of the symbolic. Indeed it might be claimed that the diagram is essentially what the good antiquarian image has to be. No matter that they may use naturalistic conventions, the point of most antiquarian images is to display data that others may wish to analyze. In many presentations this requires the purging of unnecessary visual information. This is not, however, a remark that holds good for all antiquarian images—many of which contain, on this measure, superfluous detail—and so opens them to criticism informed by progressivist and teleological understandings of the transition from antiquarian to archaeological approaches in the study of the past. The analysis offered here is not intended to buttress that position, which ignores the specific protocols that affected the production of antiquarian images in different circumstances. What it does highlight, however, is the implicit logic of the idea that the antiquarian image is ineluctably a purveyor of information; this is what led Petrie to his declaration and his insistence on the rectitude of his illustrations.

Sometimes, the beauty of the objects and the skill of the illustrator militate against this desideratum. The kinds of records made by skilled artists working in watercolor, especially those employed by the Society of Antiquaries or engaged by topographical and antiquarian publishers, demonstrate the extent to which accurate recording could find an accommodation with the aesthetic quality of fine art production. The engravings made from them were correspondingly rich in detail and vied with the best efforts of fine artists.

With woodcut illustrations, however, the original drawings from which they mostly derive do not typically exhibit the fine art qualities a connoisseur of the time would recognize. Instead, the drawings tend to be efficient functional records, and the woodcut medium used to publish them encouraged a more straightforward treatment, with no distraction from color, limited tonal variety, and a predominantly linear style.

A typical antiquarian woodcut emphasizes what the author wants the reader to notice, and what looks like a straightforward copy of the original motif is, in fact (and necessarily), a discriminating and focused vision.

How, then, should we investigate Hanlon's illustrations? Can we reconcile Petrie's description of them as "quotations" with the selective, linear, and tendentious process that, I have suggested, is the antiquarian's customary approach to image production? To answer this question we can compare the woodcuts Hanlon supplied for Petrie and those he supplied for Wakeman and try to establish the different modes of illustration employed in those books. Although Hanlon's work for Petrie was much more extensive than it was for Wakeman (256 cuts as opposed to 91), the woodcuts share many characteristics. One obvious explanation is that Hanlon's training encouraged him to use woodcuts in a particular way, but it would be wrong, I think, to give his technique too determinate a role. Petrie and Wakeman were both capable artists in their own right and Hanlon was given the job of working from sketches they had made in the field.

Wakeman states merely that George Hanlon is "an artist of whose excellence as an engraver it is unnecessary here to speak" (Wakeman, x). And when Petrie refers to Hanlon's "anxious fidelity" he means fidelity to Petrie's original drawings, themselves made with an "anxious desire for rigid accuracy." So if the appearance of these illustrations is similar, and if their placement on the page follows the same pattern, this is not because their executant woodcutter's personality as engraver and designer was dictating the process; it is because the visual language of antiquarianism, its mode of discourse, was common to all three of the men involved.

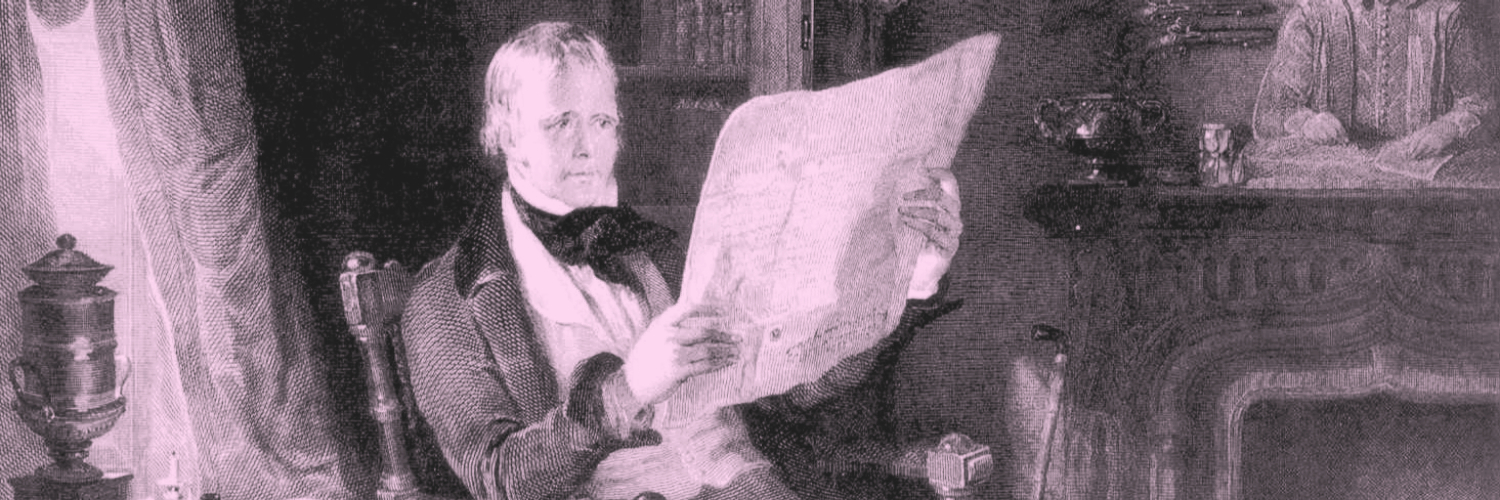

Fig. 1 George Petrie, Inquiry into the Origin and Uses of the Round Towers of Ireland (Dublin, 1845), 76.

That singular expression, "mode of discourse," is apt insofar as anyone turning the pages of these books would not detect major differences in style from image to image; the overarching visual language is, to that extent, consistent. But there are, nevertheless, different approaches adopted for three different classes of image, and these may be graded nearer to or further away from Petrie's idea of "quotation" from the original object. There are a few images which are essentially diagrams, either showing sections of architecture or comparative arrays of artifacts (Fig. 1). With these may be grouped those illustrations inserted into the text to substantiate a point in visual terms, but which do not attempt to engage the reader aesthetically, and although not diagrams per se, they do operate diagrammatically. Petrie's more generous provision of illustrations allows him to include much more of this kind of material than does Wakeman, and this profusion of visual examples helps anchor his argument throughout. There is a further class of illustration that makes use of a properly three-dimensional representation but only displays that fragment of it which is necessary for the point made in the text (Fig. 2).

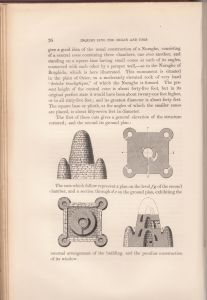

Fig. 2 George Petrie, Inquiry into the Origin and Uses of the Round Towers of Ireland (Dublin, 1845), 301.

Most of these are economical and practical to a degree, supporting a line of argument, but the addition of superfluous detail in some of them shows a willingness to go beyond the strictest needs of scholarship.

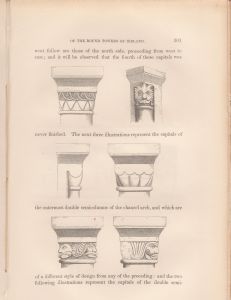

Fig. 3 George Petrie, Inquiry into the Origin and Uses of the Round Towers of Ireland (Dublin, 1845), 412.

Distinguished from these woodcuts, however, are the vignette illustrations of prehistoric and medieval structures, which Petrie always lists as "views" (Fig. 3). By and large, all of these vignette illustrations are visually composed, they make full use of light and shade to articulate the object in question, and they include some of its landscape surroundings. The visual language here is tinged with the picturesque idiom one finds in contemporary illustrated tours, and in some cases these vignettes are indistinguishable from their equivalents in a book of picturesque beauties.

The view format is where the idea of accurate "quotation" is at its weakest, for the antiquarian image cannot now distinguish itself from better established habits of visual engagement. The representation is too rich to be assimilated as a demonstration of a point, and its abundance of detail frustrates cognitive clarity. In these cases the spectator's customary aesthetic approach threatens to overwhelm the author's scholarly concerns. Here, surely, Hanlon's woodcuts evince more than "slight pretensions to the character of works of art": they are relatively "showy," and they do include "freedom of handling, or forcible effect," precisely the qualities Petrie claimed to have banished from the book.

In these picturesque vignettes, the paramount need for accuracy has given way to other desiderata.

It would be a mistake to concentrate solely on these modes of presentation without considering wider contexts, given that image-making is both internally and externally differentiated from the overall visual matrix in which it operates. The circulation of images of Irish antiquity was not restricted to the antiquarian enterprise. Indeed, through their proselytizing for the preservation of Irish antiquities, Petrie, Wakeman, and others were fuelling a tourist interest in such remains and, beyond that, were binding Irish antiquities into a dignified historical narrative with implications that Irish nationalists were keen to develop. It is not entirely surprising, therefore, that occasionally the antiquarian and the picturesque domains of image-making overlap. Looking back over 150 years, we might regard the more picturesque images as compromising Petrie's claim of "quotation" and so detracting from the usefulness of the text from a scholarly point of view. After all, by the 1840s there existed a variety of illustrated antiquarian studies that paid scant heed to the picturesque and found their readership primarily in learned circles. But with respect to Irish antiquities and the urgent need to protect them from destruction, a text bereft of all aesthetic pleasure would have missed its chance to gain a large readership. By using copious amounts of woodcuts and including a variety of visual devices Petrie and Wakeman had an opportunity to disseminate sound antiquarian research very widely and help in the construction of a valid history of Ireland, a shared patrimony. In that sense, quotation could perhaps be accompanied by exhortation.