Michel-Rolph Trouillot begins his essay, “From Planters’ Journals to Academia: The Haitian Revolution as Unthinkable History,” with an anecdote. In 1790, a planter in Saint Domingue writes a series of letters to his wife in France reassuring her that the Revolution has not spread to the Caribbean. He writes, “There is no movement among our Negroes . . . . They don’t even think of it. They are very tranquil and obedient. A revolt among them is impossible” (Trouillot 81). Apparently, all was quiet on the (French) Western front. There was no sign of an organized slave revolt. The thought of an uprising was “impossible.”

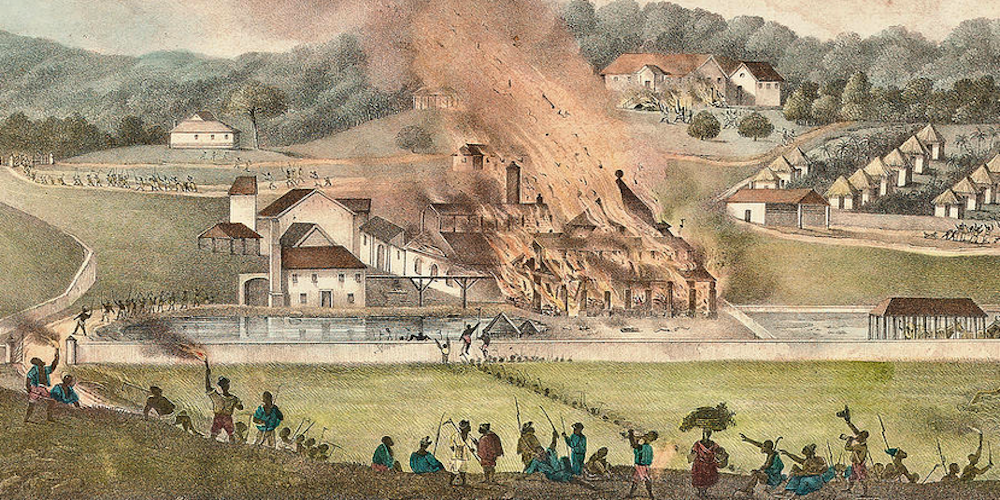

In August of the following year, the Haitian Revolution began. The irony of this story is not lost on Trouillot, who explains: ‘The Haitian Revolution thus entered history with the peculiar characteristic of being unthinkable even as it happened. Publications of the times, including the long list of pamphlets on Saint Domingue published in France from 1790 to 1804, reveal the incapacity of most contemporaries to understand the ongoing Revolution on its own terms. They could read the news only with their ready-made categories, and these categories were incompatible with the idea of a slave revolution. (82) ’ Trouillot chalks up the planter’s ignorance to a larger world view shaped and shared by slave owners about enslaved peoples. He argues, “When reality does not coincide with deeply-held beliefs, human beings . . . phras[e] interpretations that force reality within the scope of these beliefs. They devise formulas to repress the unthinkable and to bring it back within the realm of accepted discourse” (Trouillot 81). In short, the planters were in denial. To believe that the principles of the French Revolution could be adopted by slaves in Saint Domingue required that planters not only acknowledge the humanity of slaves, but also admit that stereotypes and misinformation spread about their intellectual abilities were untrue. Identifying with revolutionary principles and, more importantly, rising in arms en masse in order to defend those principles required both intellectual and military prowess—two things that French colonists living in Saint Domingue during the French Revolution preferred to deny. As one may easily guess, the idea of a mass slave revolt would have been a frightening image for slave owners in Saint Domingue (where slaves outnumbered the free population by ten to one) after the revolution broke out in France 1789. Nevertheless, it was the image they were met with in 1791. A well-organized slave revolt turned into a full-scale revolution that lasted until 1804 and led to the formation of the Republic of Haiti.

Although the Haitian Revolution is the most successful slave revolt in the Western hemisphere, it was preceded by many smaller uprisings, not only in Saint Domingue, but also throughout the Caribbean and the Americas.

Jamaica, in fact, was home to the second most successful slave revolt in the Americas just a few decades later, with the Christmas Rebellion of 1831. Jamaica was also home to several uprisings throughout the late-seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with resistance coming from both slaves and free blacks. There were at least five organized slave insurrections in the central region of the island between 1673 and 1725.

The most famous slave revolt in eighteenth-century Jamaica, Tacky’s Rebellion, occurred in the spring of 1760 in St. Mary Parish and took several weeks to quell. An existing copy of the record book of slave trials in St. Andrew Parish (located just south of St. Mary) lists 56 individual cases of “rebellious” activities prosecuted between 1746 and 1782, including not only violent offences, but also the harboring of runaway slaves and possession of obeah materials.

English colonists in Jamaica also fought multiple wars against free blacks in the eighteenth century. The First Maroon War lasted four decades and ended with two treaties signed in 1739 and 1740; the Second Maroon War occurred in 1795-96. Both conflicts posed serious threats to the European colonists with regard to both the cost of troops and the financial burdens of war. In the four decades leading up to the culmination of the First Maroon War, the Jamaican Assembly passed 44 acts and spent £240,000 before signing treaties with the Maroons (Robinson 38). The eight-month long conflict with the Trelawny Town Maroons in 1796 is estimated to have cost between £350,000 and £500,000. “All this,” Mavis Campbell points out, “to quell just over 150 arms-bearing Maroons” (244). Yet, despite their relatively small numbers, the Trelawny Town Maroons were not to be underestimated. An early nineteenth-century history by R. C. Dallas details the feared outcome of not taking every expense necessary to end the Second Maroon War. He writes as follows: ‘[The Trelawny Town Maroons] threatened the entire destruction of the island; for had this body of Maroons evinced that their rebellion was not a temporary struggle, but a permanent and successful opposition to the Government, it is highly probable that the example might in time have united all the turbulent spirits among the slaves in a similar experiment . . . such a decided triumph might have tempted numbers of the plantation negroes, unwilling before to change a state of peace for warfare, to join the Maroons: at all events they would have been a rallying point for every discontented slave . . . . The lives of the colonists must have been spent in continual terror; massacre and depredation would have spread throughout the country . . . . (2-3)’ According to Dallas, any expense taken to remove the Maroon threat in 1796 was worth it. The above passage explicitly expresses a fear of mass revolt on the part of both Maroons and slaves that is much larger in scale than actually occurred in Trelawny Town.

So, why was Dallas convinced that the expense was worth it? Because the threat posed by the Saint Domingue Revolution was very real. News of the rebellion in Saint Domingue spread quickly to Jamaica. “Within a month after the August uprising in St. Domingue,” writes David Geggus, “slaves in Jamaica were singing songs about it” (276). British planters on the island took note. Using a wide range of primary material, including the governor’s correspondence, Geggus describes the subsequent months as follows: ‘By November, whites were complaining of “insolent” behavior and that the slaves had become “so different a people from what they were.” “I am convinced,” wrote one master, “that the Ideas of Liberty have sunk so deep in the minds of all Negroes, that whenever the greatest precautions are not taken they will rise. “Head negroes” were overheard talking of killing whites and dividing up their lands. “Negroes in the French country,” they said, “were men.” (Geggus 277)’ According to the picture painted here, Jamaican planters and French planters were obviously on opposite sides of the spectrum with regard to acknowledging the potential threat of being vastly outnumbered by slaves. Yet, the Jamaican planters’ fears were never fully realized. After 1792, rebellious activity on the island decreased over the next decade when compared to the previous three decades. After 1792, the initial cause for alarm greatly subsided and all but vanished from existing documents.

For Geggus, the answer to the paradox as to why Jamaica remained stable during the Haitian Revolution is quite simple. British military presence was key. Slave resistance in the British Caribbean was low during the Age of Revolution for the following reason: ‘It was precisely during the years 1776-1815 that Britain’s military presence in the region was at its peak. . . . . The British colonial garrisons were boosted during the American War of Independence, and they were not cut back to prewar levels in 1783. . . . . A succession of international crises ensured that, when the St. Domingue slave revolt broke out, there were already more soldiers in Jamaica than ever before in peacetime. (Geggus 293)’ The worrisome tone that underscored the earlier examples provided by Geggus vanished quickly because British military presence kept rebellious activity at a minimum after 1792. Within months the tone had completely shifted, and the island’s planters were calm.

‘The impact of the St. Domingue Revolution on Jamaica’s slaves appears to have been slight . . . . The slaves did not revolt . . . . Yet the initial reaction to the 1791 uprising had been one of excitement and admiration accompanied in some quarters by a desire to emulate it. Quite possibly planters covered up minor incidents on their own estates, and there can be no doubt that they wished to avoid giving an impression of public alarm that might damage their all-important commercial credit. (Geggus 288)’ The English had their assurances that the island was tranquil. Public documents gave no indication of unrest among the slaves.

The history laid out above demonstrates that the opinions of planters in Saint Domingue in 1791 lay in stark contrast to the ideas of planters in Jamaica shortly thereafter. Similarly, the French colony and British colony would take very different trajectories over the next decade. However, there is one trend that French and British literature about black resistance in the Caribbean shared during the same period. Despite the fact that all of the colonies in the Caribbean had their share of revolts both small and large, many historical and literary sources written by European colonists misrepresented mass revolts (even denied them) by focusing on isolated incidents involving one or two individuals, as opposed to well-organized, collective rebellions. Trouillot again gives us a useful summary of the reports from Saint Domingue immediately preceding the Haitian Revolution: ‘Close as some were to the real world, planters and managers could not fully deny resistance, but they tried to provide reassuring certitude by trivializing all its manifestations. Resistance did not exist as a global phenomenon. Rather, each case of unmistakable defiance, each possible instance of resistance, was treated separately and drained of its political content. Slave A ran away because he was particularly mistreated by his master. Slave B was missing because he was not properly fed. Slave X killed herself in a fatal tantrum. Slave Y poisoned her mistress because she was jealous. The runaway or the rebellious slave emerges from this literature . . . as an animal driven by biological constraints . . . . This is not “a man in revolt” . . . but a maladjusted Negro . . . . (Trouillot 86)’ Although he is referring to reports written by French colonists in Saint Domingue, Trouillot’s “unthinkable history” of organized black resistance also applies to English representations of Jamaica at the turn of the nineteenth century that appeared both in print and on stage just as the French lost control of their own Caribbean colony.

The misrepresentation of collective rebellion just outlined also characterizes the history of Three-Fingered Jack in English popular culture.

“The Terror of Jamaica” in England

The story of Three-Fingered Jack (the escaped slave who terrorized the British colonists in Jamaica from 1780 to 1781) appeared in England in at least five major versions between 1799 and 1830. These adaptations included Benjamin Moseley’s Treatise on Sugar (1799), William Earle’s novella Obi; or, The History of Three-Fingered Jack (1800), a pantomime by John Fawcett titled Obi; or, Three-Finger’d Jack (1800), a sixty-page pamphlet by William Burdett titled Life and Exploits of Mansong, Commonly Called Three-Finger’d Jack, the Terror of Jamaica (1800), and finally Obi; or , Three-Fingered Jack, a melodrama by William Murray (1830). Although different in their respective politics and approaches, these five nineteenth-century version of the story deemphasized the collective threat posed by Three-Fingered Jack’s exploits in 1780-81.

Although he was notoriously dubbed the “Terror of Jamaica,” Three-Fingered Jack is loosely tied to the Haitian Revolution in contemporary scholarship. In the article that introduced Three-Fingered Jack to twentieth-century readers, Alan Richardson shows that the popularity of this story in the first decade of the nineteenth century fits into a larger trend in English literature and popular culture much like the one outlined by Trouillot. Richardson’s piece demonstrates how English representations of obeah generally played up the most sensational aspects of the African tradition in an attempt to cover up the more unsettling reality of black uprisings in the West Indies. Voodoo priests were partly responsible for several organized revolts in Saint Domingue including the 1791 rebellion that began the Haitian Revolution.

Similarly, obeah men were responsible for several uprisings in Jamaica throughout the eighteenth century, the most famous being Tacky’s Rebellion in 1760, which led to the outlawing of the practice on the island.

Although there is no hard evidence proving that Three-Fingered Jack was involved in obeah rituals, obeah made its way into the story of Three-Fingered Jack beginning with Moseley’s 1799 account. The following year, his name became synonymous with the practice with the appearance of three popular adaptations including Earle’s novella, Fawcett’s pantomime, and Burdett’s account. The popularity of the story of Three-Fingered Jack at the height of the Haitian Revolution makes sense. Richardson explains, “In the defeat of Jack and of obi with him, the ‘Terror of Jamaica’ and the ‘Horror’ of Saint Domingue could be symbolically exorcised” (Richardson 19). Richardson sees the obvious subtext of the Haitian Revolution written into Fawcett’s pantomime. However, unlike the revolution in Saint Domingue, the story of “The Terror of Jamaica” ends with the colonial government’s authority restored, partly through the containment of rogue religious and rebellious practices. The addition of the obeah storyline into the popular English history of Three-Fingered Jack certainly invites such conclusions.

However, the defeat of obeah in the English adaptations of Three-Fingered Jack was not the only way that the popular history was rewritten at the turn of the nineteenth century in order to shape popular understanding of black resistance in the West Indies. The English adaptations misrepresented the history of collective resistance in Jamaica in two major ways. First, Three-Fingered Jack, the leader of a gang of sixty rebels, became a lone rebel. Stripping Jack of his followers made the story appear to be an isolated incident, as opposed to a collective effort. Moseley and Murray erase Jack’s gang in their versions of the story. Earle and Fawcett give Jack a few rag-tag followers, but neither acknowledges the actual size and loyalty of Jack’s gang. Only Burdett makes Jack the leader of a large group of slave rebels; however, his account quickly dispatches of the gang that eluded government officials for more than one year.

The second way that Three-Fingered Jack’s popular history in England ignored the actual history of black resistance and independence in Jamaica was by changing the identity of Jack’s captor from a Maroon to a slave. All of the nineteenth-century adaptations of the story of Three-Fingered Jack misrepresent the identity of Jack’s killer. Whether intentional or not, this change completely distorted the story of Three-Fingered Jack by ignoring the role that free blacks played in restoring order to the island. Most of the adaptations contain no free black characters in the story. The two major changes to the story rewrote the history of Three-Fingered Jack so that it (like other stories of slave insurrections in the West Indies) was depicted as an isolated incident as opposed to a link in a chain of organized rebellions that occurred in the European colonies in the Caribbean in general, and Jamaica in particular, during the decades leading up to the Slave Trade Act of 1807, and later full emancipation through the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

According to Diana Paton, the popularity of Three-Fingered Jack during the first three decades of the nineteenth century is undeniably tied to English abolition debates. The story of Three-Fingered Jack was particularly appealing for nineteenth-century writers because it could be used to argue both for and against slavery. Paton explains as follows: ‘The cumulative impact of the cultural figure of Three-Finger Jack was not to a produce a coherent argument regarding the slave trade or slaver. Rather, representations of Jack could be adapted and adopted by those on all sides of the slavery debates. Nevertheless, the easiest fit was with a gradualist and ameliorationist viewpoint; potentially hostile to the slave trade, but not emancipationist. Criticisms made by the prose and stage versions of Three-Fingered Jack could be reconciled with the continuation of slavery. (59) ’ Paton argues that the shift in British public opinion that led to full emancipation less than three decades after Three-Fingered Jack became a household name in London motivated Murray to give a more sympathetic portrayal of Jack in the 1830 melodrama. This may be true to some extent; however, the massive overhaul made to the story by its earliest English adapters forever changed the popular history of Three-Fingered Jack’s rebellion.

There is some disagreement among scholars as how best to approach the various adaptations of the story given the diverse range of political sympathies expressed in each. For example, Earle’s novella is fervently abolitionist in its presentation of Jack’s story. The pantomime by Fawcett, on the other hand, is hardly radical in tone. Instead, the Fawcett pantomime, as Robert Hoskins explains, ‘. . . is woven into the imperial age. The site of the plantation is assumed ripe for commercial exploitation and political control. The moral and civic imperative is to impose the unquestioned superiority of Western civilization on new lands and peoples. This mind-set in itself assumes juxtaposition and conflict of opposites—civilization versus savagery and a tamed, pastoral nature versus an untamed wilderness. Thus Afro-Caribbean society and Jack as black insubordinate by definition became that dangerous or unpleasant Other. (Hoskins par. 6)’ Jeffrey Cox agrees that an overarching conservative ideology dominates Fawcett’s pantomime; however, he sees moments where “aspects of Jack's story and of his culture break free from the play's ideology,” and suggests that these moments of subversion were possible in performances (depending on the cast, venue, and audience), if not explicitly expressed in its printed songs and scene descriptions (Cox par. 7).

James O’Rourke’s recent article on Murray’s 1830 melodrama argues that the play is full of Jacobin sympathies, specifically because Jack’s character undergoes major development from the 1800 pantomime. He writes, “the 1830 Obi is . . . in fact a Jacobin play, both in its legitimation of the violence of the oppressed and underclass and in the repudiation of its inherited romantic plot” (O’Rourke 286).

This observation is accurate insofar as the two popular dramas are concerned. Cox and Paton also agree that Three-Fingered Jack was cast in a more sympathetic light on the 1830 stage when compared to the 1800 pantomime. Most notably, Murray’s addition of spoken lines delivered by Ira Aldridge (the first black actor to portray the Jamaican folk hero) introduced radical possibilities in the performance of the melodrama that were absent from the 1800 pantomime. However, the 1830 melodrama hardly sounds radical when compared to Earle’s abolitionist novella, which actually introduces Three-Fingered Jack as “a bold Defender of the Rights of Man.”

(You really can’t get more “Jacobin” than that.) O’Rourke’s reading is a convincing comparative reading of the two plays, but is less convincing when one considers all of the nineteenth-century adaptations in unison, and then compares them to the historical record.

There is validity in all of the readings outlined above, especially since there is no way to gauge how different readers and theatergoers may have interpreted any of the adaptations produced in the nineteenth century. However, what is very clear is how the nineteenth-century versions of the story simplified the events leading up to Three-Fingered Jack’s demise either by erasing an entire population of free blacks from the narrative or at least drastically downplaying their role in the defeat of Three-Fingered Jack. My reading does not discredit existing scholarship on the subject. However, my argument questions to what extent any of the adaptations can be read as radical given that by erasing or downplaying the involvement of Maroons and by making Three-Fingered Jack a one-man show, nineteenth-century adapters failed to portray a long history of black resistance in colonial Jamaica during a period of major unrest in Saint Domingue and Jamaica.

Three Fingered Jack in Fact and Fiction

According to eighteenth-century sources including Moseley, Three-Fingered Jack was killed by a Maroon named Reeder, a free man. However, all of the nineteenth-century adaptations of the story recast Reeder as a slave named Quashee who (along with another slave named Sam) agrees to fight Three-Fingered Jack in return for his freedom (and sometimes money). Moseley, Earle, and Burdett explain the name change (contemporaneous news reports only use the name Reeder) by telling the reader that Quashee took the name Reeder after being christened in order to help him fight Jack. In the two theatrical pieces, Reeder is simply replaced by Quashee, with no name change ever taking place during the course of the play (although the christening still takes place in the pantomime).

There are two important things to note with regard to this change in the English versions. First, there is no historical evidence to support the name change to Reeder through christening. Geggus explains that by the late eighteenth century, three-quarters of Maroons had British names (284). Therefore, the only explanation for the addition of a Christian storyline is to depict the superiority of British culture and values and propagandize British imperialism through the devaluation of an African religion. (The adaptations all sensationalize obeah while discrediting it as mere superstition.) The second point to note is that the five English versions push the Maroons to the margins of the story of Three-Fingered Jack, or erase them entirely. Erasing the Maroons from the story’s afterlife in English popular culture also made it easy to depict Jamaica as a stable British colony during the time of the greatest unrest in the West Indies.

By 1780, the year of Three-Fingered Jack’s activity in Jamaica, the Maroons had a long history on the island. Maroon populations in Jamaica date back to the sixteenth century, when the island was under Spanish control. When the British gained control of the island in 1655, the Maroons refused to give up their independence. They violently resisted the British colonists, and they were very successful. Decades of confrontations ultimately resulted in the First Maroon War, which officially lasted from 1731 until 1740. Unable to defeat the Maroons, the British colonists instead entered into a series of official treaties that granted the Maroons autonomy and approximately 2500 acres (concentrated in the five towns of Trelawny Town, Scots Hall, Nanny Town, Accompong, and Moore Town). Independence and land were “granted” in exchange for assistance in quelling slave riots and capturing escaped slaves. Maroons were expected to participate in the capture of Three-Fingered Jack, and eighteenth-century Jamaican newspapers and government documents confirm that a Maroon named Reeder was in fact responsible for killing him (Aravamudan, 11-13).

The consensus in the eighteenth-century primary sources of information makes the change from Maroon to slave all the more pronounced in the nineteenth-century adaptations. The source of the confusion seems to be Moseley’s 1799 treatise, where the story of Three-Fingered Jack is included in an appendix as a subsection of an essay on obeah. The reader gets a significantly changed version of the story in Moseley’s text, which begins “I saw the Obi of the famous negro robber, Three fingered Jack, the terror of Jamaica in 1780 and 1781. The Maroons who slew him brought it to me” (rpt. in Aravamudan, 164). He refers to the man as Quashee, not Reeder as named in the reports. Why the name change? Moseley offers a simple explanation. “Quashee, before he set out on the expedition, got himself christianed, and changed his name to James Reeder” (rpt. in Aravamudan 166). Moseley’s account marks the first mention of religious conversion in the story of Three-Fingered Jack. There is no mention in any contemporary newspapers or other documentation. The absence of this information in any previous source does not necessarily mean that Moseley’s explanation is false; however, there is no primary source material to confirm Moseley’s claim.

Although Moseley never explicitly calls Quashee a slave (in fact, he calls him a Maroon), his description of Quashee is vague and likely the source of confusion among most of the later adapters. Moseley tells his readers that Jack was finally apprehended after the colonial government offered a substantial reward for his capture, as well as the promise of freedom to any slave who managed to dispatch of the menace. These rewards were in fact offered, but only the bounty was claimed since Jack was killed by a Maroon. This fact is erased in all of the adaptations that follow. From 1800 on, Quashee was always a slave. In the adaptations that follow Moseley, Quashee’s characterization ranges from an industrious slave primarily motivated by the colonial government’s financial reward and promise of freedom, to a loyal slave who earns his freedom after risking his life to defend his benevolent (and grateful) master.

Earle’s 1800 novella (without a doubt the most explicitly abolitionist adaptation of the story) also casts Quashee as a slave; however, Earle’s narrator focuses more on the bounty offered by the colonial government, rather than the promise of freedom. Disgusted by the financial reward offered for Jack’s capture, Earle’s narrator offers the following take on Three-Fingered Jack’s demise: “Thus died as great a man as ever graced the annals of history, basely murdered by the hirelings of Government” (Earle 157). Earle’s description is the most accurate of the nineteenth-century English adaptations because money did in fact play a major role in Three-Fingered Jack’s capture; Reeder collected a reward of at least £300. However, Earle’s Quashee is described as a slave working on behalf of the same government that enslaves him. This historical inaccuracy—in the most radical adaptation of the five versions produced in England, no less—not only misrepresents Reeder’s identity, but does so at the expense of recognizing the Maroons, the most significant example of free blacks living in Jamaica at the time.

Because of Earle’s abolitionist sympathies, Quashee’s actions are ultimately un-heroic in the novella; however, Earle’s characterization is a far cry from the other nineteenth-century versions of the story by Fawcett, Burdett, and Murray. Burdett’s version (also published in 1800) makes Quashee a hero, a well-deserving recipient of his dual reward. Despite its claims to historical accuracy, Burdett’s account presents Quashee as a slave fighting primarily for his freedom—the money is just an added bonus. The final lines of his pamphlet are “Reeder and Sam, gifted with freedom and the rewards, annually celebrate the fall of the once terror of the whole island of Jamaica” (Burdett 56). The order of words “freedom and rewards” is significant. Fawcett, Burdett, and Murray all focus on the reward of freedom; in fact, the two stage adaptations mention only this reward. By 1800, this became the standard storyline for Quashee. In other words, Earle’s characterization of Quashee as a government mercenary faded as soon as it was introduced because it was overshadowed by less radical adaptations with a wider popular reach.

Unlike the textual accounts, which give Quashee/Reeder more agency in his decision to pursue Three-Fingered Jack, the theatrical adaptations characterize him as a loyal slave whose duty to his master is rivaled only by his dedication to his own family. Fawcett’s pantomime presents Quashee and Sam as loyal fathers fighting for freedom. Their duty to their wives and children is presented alongside subservience to the owner of the plantation. This sentimental characterization would certainly raise the eyebrows of today’s readers, but was a typical characterization of slaves in literary and theatrical productions that argued for abolition of the slave trade, if not for full emancipation.

This characterization is taken to a greater extreme in the 1830 melodrama where Quashee’s motivation for fighting Jack is presented as a humble slave’s loyalty to a benevolent owner, which is made explicit at the end of the melodrama’s first act: ‘QUASHEE. (with great feeling) Massa! you have been kind massa to me; and Missee Rosa been kind missee to wife and pickaninny here, and I now show you black man's heart beat warm as white. I will go; and if I meet this Jack, Quashee will kill him, or him kill Quashee, only if poor nigger die, you take care of wife and little Massa Quashee. (Act I, Scene vii)’ Quashee puts his life on the line in order to defend his master’s family. All that he asks in return is that his “Massa” will look over his wife and child should he be killed in the conflict. Quashee’s loyalty is rewarded with freedom at the close of the melodrama, giving this final popular adaptation of the legend of Three-Fingered Jack an exaggerated sentimental tone that completely contradicts the historical record as far as scholars have been able to piece it together.

The stories presented in both the 1800 pantomime and the 1830 melodrama are ridiculous when compared to the reality of Three-Fingered Jack’s defeat at the hands of a Maroon. Although the Maroons in Jamaica were required to work with the colonial government as a condition of their autonomy, this group was in not subservient to government officials or planters in the way that is suggested by the nineteenth-century adaptations of the story. As mentioned earlier, fifteen years after Three-Fingered Jack was killed in Jamaica and five years before he was resurrected through adaptations in England, the Trelawny Town Maroons were involved in a violent eight-month-long insurrection against the colonial government. In 1796, the government, once again unable to control the Maroons, shipped the Trelawny Town Maroons to Nova Scotia. Most of the Maroons involved in this transportation eventually resettled in Sierra Leone in 1800, the same year that a Maroon named Reeder was transformed into a slave named Quashee for the entertainment of English audiences.

The historical inaccuracies in presentations of the Quashee/Reeder character may be attributed to innocent errors on the part of Earle, Fawcett, and Murray who, as far as we know, did not spend time in Jamaica prior to authoring their adaptations. However, the versions written by Moseley and Burdett are a different case. For example, Moseley’s explanation that Quashee and Sam were “allured by the rewards offered by Governor Dalling . . . and by a resolution which followed it, of the House of Assembly,” implies that the promise of freedom played a part in motivating these men to confront Three-Fingered Jack. This statement contradicts Moseley’s earlier claim that he once met the Maroon who defeated Jack, as well as his explanation that both Quashee and Sam were both of Scots Hall, Maroon Town. Moseley, who spent time in Jamaica prior to publishing his 1799 treatise, would know the difference between a Maroon and a slave. His vague version of the story comes across as rather disingenuous given his otherwise meticulous descriptions of the cultural practices, geography, and economy of Jamaica.

The same error also seriously undermines the credibility of Burdett’s account. Like Moseley, Burdett explains that Quashee and Sam are from Scots Hall, Maroon Town. Nevertheless, he describes Quashee as “the Slave who, some time before, in a battle, had cut off Jack’s two fingers,” and that Quashee was once an “intimate of Jack’s in his days of slavery” (Burdett 46, 35). These claims are blatantly false. Similar discrepancies can be found in his characterization of Mr. Chapman, who Burdett describes as “an eminent Planter in Maroon’s Town,” despite the fact that there were no white planters in any area belonging to the Maroons (Burdett 37). Chapman’s character is likely based on white superintendents, appointed by the Governor, who lived in Maroon settlements according to the terms of the treaties signed between Maroons and the colonial government. Carey Robinson describes the duties of superintendents as chiefly maintaining friendly relations between the government and the Maroons. Superintendents also resolved disputes among Maroons, held court alongside four other Maroons, and reported to the Governor every three months regarding the population, crime, and the condition of the roads of the town where they resided (Robinson, 64-65). Although superintendents were granted significant authority in the officially-sanctioned Maroon communities, they were not slaveholders. There is no basis for Burdett’s Chapman, at least not the way that he is presented to readers. It is hard to believe that a “many years overseer of a Jamaican plantation,” as Burdett claims to be, would make such a critical error, especially in 1800, less than five years after the Second Maroon War, which was widely reported in English publications.

The factual errors in Burdett’s version are particularly disturbing because the author presents his account as a history written to provide contextual information for Fawcett’s popular pantomime. From the onset, the publication is put forth as an educational tool meant to be read as a history. Burdett’s version of the story is billed as a “Narrative of Facts” on which “the Public may depend” (iv). However, as anyone acquainted with the history of Three-Fingered Jack would note, Burdett’s history is largely a fiction, and Paton even describes it as a novel.

Burdett draws explicitly upon Bryan Edwards’s History of the West Indies and Moseley’s works; however, these sources are used to paint a detailed picture of obeah as a practice, not Three-Fingered Jack the person.

The historical inaccuracies in the portions of the text that deal specifically with Three-Fingered Jack are apparent from the onset. The first ten pages of Burdett’s history cover Jack’s life in Africa among warring tribes, his capture by his enemies, his sale to a slave merchant headed for Jamaica. This is a fascinating story; however, to date there is no proof that Three-Fingered Jack was born in Africa. The liberty that Burdett takes with the tale of Jack’s origins is similar to Earle’s novella. However, Earle’s novella is clearly a work of fiction, whereas Burdett’s version of the story floats back and forth between fact and fiction.

For example, about a third of the way through Burdett’s adaptation of the story, he includes a lengthy digression about obeah and the role that it played in the “formidable insurrection” that occurred in St. Mary Parish in 1760. Here Burdett is drawing on actual events. The insurrection is Tacky’s Rebellion, and Burdett is correct in explaining that the insurrection led to the outlawing of obeah. The historical digression lends Burdett’s account historical credibility. When Burdett returns to Three-Fingered Jack, the author brings up another actual uprising—the attack on Crawford Town on February 10, 1780, which burned the community to the ground. Burdett claims that Three-Fingered Jack was the leader of this organized attack. However, as L. Alan Eyre has explained, “The burning of Crawford Town certainly did take place, but there is no other evidence [aside from nineteenth-century accounts] that Jack took part in it” (12).

The conflation of these two separate events—the burning of Crawford Town and Three-Fingered Jack’s year-long run—is significant. Making Jack responsible for the attack on Crawford Town is one way that Burdett’s self-described history by a former planter resembles the planter’s journals from Saint Domingue discussed earlier. In this example we see two independent, organized rebellions portrayed as a single event. The result is the appearance that these were orchestrated by a single man and, therefore, not widespread. The two incidents did in fact around the same time and in the same general vicinity; however, conflating the burning of Crawford Town with Three-Fingered Jack’s activities ignores the range of rebellious activity from the island’s dispersed and diverse black populations.

Despite acknowledging that Crawford Town was completely destroyed by this uprising, the author wraps up the anecdote with a decisive victory for the colonial government. According to Burdett: ‘The Governor sent five hundred choice Maroons in pursuit of those rebels. They met—they fought; the negroes, as before, rushed upon their guns, but the Maroons firing as they retreated, kept them at bay, and made a great slaughter. –Jack encouraged his men, but could not rouze them to the combat, and they fled in every direction. The next day, the Governor published a pardon to such of the insurgents as would return to their duty; this had the desired effect; for they all returned, except Jack, who was still determined to harass the European settlers. (Burdett 33)’ This account is yet another example of the gross discrepancies found in Burdett’s version. Contemporaneous news reports date the disbanding of Jack’s gang in December 1780, ten months after Crawford Town was set ablaze. While it may be true that Governor Dalling issued a pardon for slaves involved in that incident, he did no such thing for Jack’s band of rebels. In fact, by the end of 1780, a reward of £5 was issued for the capture of any of Three-Fingered Jack’s accomplices. Admittedly, this bounty was nowhere near the £300 reward offered for their captain, but the situation was not resolved as easily as Burdett claims in his version of the story.

Burdett’s account of the Crawford Town incident is also interesting because it is the only appearance of Maroons in the text. Burdett uses the word “Maroon” exactly four times in his account, but this is the only time that he uses the word to describe a group of residents on the island.

The term is never defined. The Maroons’ cameo is misleading to say the least. They are depicted as foot soldiers in the service of the colonial government when, in truth, their relationship to the plantocracy (as well as with slaves) was much more complicated than Burdett would have his readers assume.

What could have led Burdett to make such an obvious mistake? Paton offers a few suggestions. She explains that “the British understanding of the place of black people in the Caribbean located them firmly as slaves,” and the adaptations produced in England did nothing to challenge those assumptions, presumably because it was deemed unnecessary (or undesirable). “Maroons, as autonomous black characters, even if tied to the plantocratic state through treaties, would have disrupted such a vision” (Paton 52). This argument holds up for all of the English adaptations. Although Paton defends Earle and Burdett for at least acknowledging the presence of the Maroons, the passage cited above clearly shows that Burdett’s account only brings in the Maroon soldiers to move the action along. He never gives a definition, nor explains to his readers that Maroons were free blacks living in independent areas gained through treaties with the colonial government. There is no mention that their military skill was perhaps stronger than the British soldiers on the island, and that the treaties signed were the only way that the colonists could “control” the island. Granted, most English newspapers also omitted these facts, and other sources also misrepresented Maroons (Moseley, for example). However, his inclusion of the Maroons is ultimately so misleading that he may as well have omitted them entirely from the story as the stage adapters did.

I agree with Paton’s explanation of the misrepresentation or omission of the Maroons in the English adaptations because they challenged conventional categories that many would have been interested in upholding. However, Paton is less convincing in her final explanation for Quashee’s change from Maroon to slave in the nineteenth-century adaptations. “Forgetting the maroon status of Jack’s killers also made sense because the tension it raises was less relevant to British audiences than to Jamaican” (Paton 52). Her reasoning is that Jamaican audiences would have understood the strained relationship between Maroons, slaves, and the colonial government directly caused by the conditions laid out in the treaties signed between the free blacks and the white colonists. These nuances are lost in the English adaptations. ‘In becoming a British story told about Jamaica, rather than a Jamaican story, Three-Fingered Jack lost sight of the complex relationships and strategic difficulties among different segments of those struggling and negotiating with plantocractic power, substituting a more straightforward vision of social relations in which there were only two sides to choose from: with Jack, or with the social order of slavery and the plantation. (Paton 53) ’ The English adaptations certainly simplify the story into a black-and-white narrative with no shades of gray; however, the consistent erasure of the Maroons from the English adaptations suggest that there was more to the revisions made to the story than merely a question of its “relevance” to British audiences. The Maroons were certainly relevant to both Jamaicans and Britons, especially only four years after the Second Maroon War. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that affording the Maroons their proper place in the popular history of Three-Fingered Jack would have required Britons to face the reality of black resistance in Jamaica, just as the greatest slave revolution in history was taking place on a neighboring island, and only a few short years after the Maroons were able to sustain an eight-month long conflict against British authorities.

If Burdett actually spent time in Jamaica as the overseer of a plantation as he claims, then his failure to provide an accurate representation of the Maroons and their continued resistance against the plantocracy is similar to the “objective” accounts of life in the West Indies by French planters outlined by Trouillot at the beginning of this article. If Burdett only claimed to be an authoritative source that his readers could rely on for accurate information, then his version of the history of Three-Fingered Jack was a fiction that followed the same strategies used by actual planters in order to promote a particular agenda. In the case of Burdett’s adaptation of the story, the politics of the piece are clearly laid out in his description of Mr. Chapman, the supposed eminent planter from Maroon Town: ‘Mr. Chapman was a good man, and very generally beloved; his slaves appeared all happy; and his plantation was esteemed the most thriving in the island. This may very readily be imputed to the willingness with which the negroes laboured for so good a master; and we can assert, from experience, that if every planter in Jamaica were to follow his humane example, it would not only tend to increase their own private wealth, but the good of the country at large; and it is indisputably as easy for a master to gain the love of his slaves as their hatred. (42)’ Whether or not Burdett actually spent time as a planter in Jamaica is uncertain; however, his sympathies obviously lie with the “benevolent planter” characterization widely circulated during the decades leading up to abolition.

Obviously, the story of Three-Fingered Jack was well known and could not be denied. The story had also proved to be quite popular and profitable in England, and Burdett even includes a scene-by-scene description of Fawcett’s pantomime as an appendix to his own publication in order to capitalize on its success.

However, although it did not make any sense to deny the story of Three-Fingered Jack from a financial perspective, it also did not make much sense to give an accurate history of the rebel slave and his death at the hands of Maroons. To accurately depict the Maroons in the English adaptations of the story of Three-Fingered Jack would have been to admit that the colonial government did not have complete control over black populations in Jamaica. Pushing the Maroons to the margins of this historical event effectively erased a history of black resistance in Jamaica from this popular story at precisely the time that the most successful slave revolution in the Western Hemisphere was at its peak.

The Haitian Revolution that produced “unthinkable” moments in prose coincided with both the Second Maroon War in Jamaica and the appearance of four of the five English adaptations of the story of Three-Fingered Jack. The fact that the adaptations by Moseley, Earle, Fawcett, and Burdett significantly downplay the real possibility of revolution and resistance from Jamaica’s black populations demonstrates that Trouillot’s analysis of documents produced about the revolution in Saint Domingue may be easily applied to English representations of Jamaica. However, the extent to which they reveal British anxieties about the spread of revolution to their own colonies is unclear, mostly because of the military’s strong presence in the region. The end of Fawcett’s 1800 pantomime—where all characters including the chorus of slaves sing “God Save the King”—certainly presented English audiences with a confident image of the island’s stability.

All of the nineteenth-century adaptations of the story of Three-Fingered Jack fail to acknowledge the possibility of a massive slave rebellion inherent in both the historical event they were adapting and the more immediate examples of resistance and revolution taking place in the West Indies at the turn of the nineteenth century. The adaptations of the story of Three-Fingered Jack are especially useful in showing how nineteenth-century English accounts changed the politics behind the events that transpired in Jamaica in the late eighteenth century. Collectively, the adaptations demonstrate how an instance of collective rebellion could be sensationalized to the point of being rendered politically insignificant. As such, the popular history of Three-Fingered Jack should be read as part of a broader history of misrepresenting black resistance and independence in the Caribbean. The nineteenth-century adaptations of the story show that even though the history of black resistance and independence was not wholly “unthinkable,” it was nevertheless an unfolding history that these writers preferred not to think about. More importantly, ignoring the possible tensions in Jamaica was a luxury only afforded by a strong British military presence on the island. The end result was that the story of Three-Fingered Jack, just like many stories of the West Indies, allowed English audiences to imagine Jamaica as a colony in close proximity to Saint Domingue, but closed from its revolutionary influence.

Works Cited

- “Introduction” Obi; or, The History of Three-Fingered Jack Srinivas Aravamudan (ed.) 2005. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview. pp. 7-52.

- Life and Exploits of Mansong, Commonly Called Three-Finger’d Jack, the Terror of Jamaica in the Years 1780 & 1781: With a Particular Account of the Obi1800. Sommers Town: A. Neil.

- The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655-1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal 1988. Granby, Mass: Bergin & Garvey.

- “Theatrical Forms, Ideological Conflicts, and the Staging of Obi” Romantic Circles Praxis Series Charles Rzepka (ed.) August 10, 2009. Obi.

- The History of the Maroons, from Their Origin to the Establishment of Their Chief Tribe at Sierra Leone Vol. 2. 1803. London: Longman.

- Obi: Or, the History of Three-Fingered Jack Srinivas Aravamudan (ed.) 2005. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview.

- “The Enigma of Jamaica in the 1790s: New Light on the Causes of Slave Rebellions” The William and Mary Quarterly (April 1987). vol. 44.2 pp. 274-99.

- “Savage Boundaries: Reading Samuel Arnold's Score” Romantic Circles Praxis Series Charles Rzepka (ed.) August 11, 2009. Obi.

- Jack Mansong: Bloodshed or Brotherhood Jamaica Journal (1973). vol. 7.2 pp. 9-14.

- “The Revision of Obi; or, Three-Fingered Jack and the Jacobin Repudiation of Sentimentality” Nineteenth-Century Contexts (2006). vol. 28.4 pp. 285-303.

- “The Afterlives of Three-Fingered Jack” Slavery and the Cultures of Abolition: Essays Marking the Bicentennial of the British Abolition Act of 1807 Brycchan Carey, Peter Kitson (eds.) 2007. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer.

- “Romantic Voodoo: Obeah and British Culture, 1797-1807” Studies in Romanticism (1993). vol. 32 pp. 3-28.

- The Fighting Maroons of Jamaica 1969. Kingston: William Collins and Sangster.

- “From Planter's Journals to Academia: The Haitian Revolution as Unthinkable History” Journal of Caribbean History (1991). vol. 25 pp. 81-99.