On October 17, Haiti commemorates the assassination of its revolutionary hero and first head of state, Jean-Jacques Dessalines (ca. 1758-1806). Haiti dignifies no other individual with an official national holiday. Haiti’s Père de la Patrie was born a slave in what was at that time France’s most valuable colony, Saint-Domingue. There are few extant details of his personal life and thoughts. In his early life, he seems to have been most noted for his ugliness and the extent of his scars. And most accounts agree that within the strictly stratified society of Saint-Domingue, Dessalines began life at the absolute bottom: he had the infinite misfortune of being the black slave of a black master who brutalized him with frequent floggings (Harvey, 21; Heinl, 88). All this would change for Dessalines, however, when the enslaved laborers organized and rebelled.

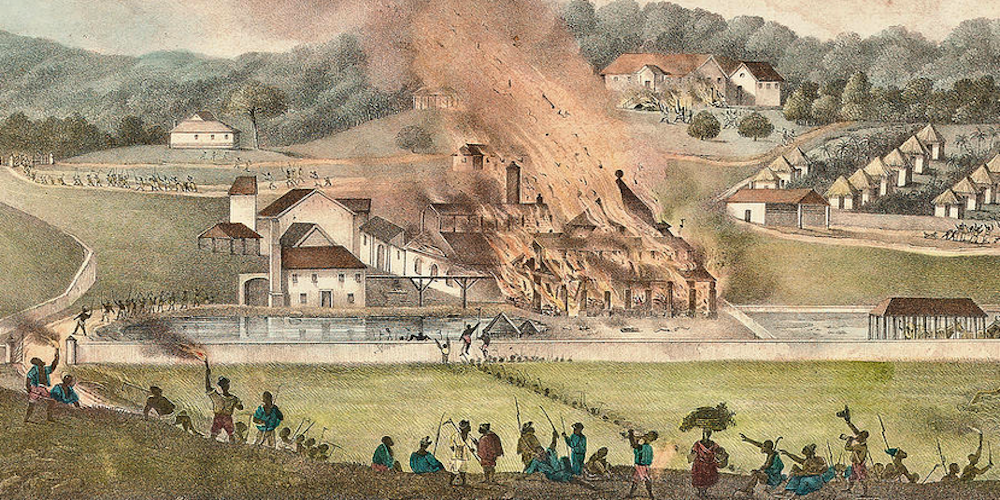

The complexities and amazing extremes of this slave-to-emperor’s biography cannot be separated from the extraordinary times and place in which he lived. It would not be hyperbole to proclaim that the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) was the most signal and transformative event in the Age of Revolution. Saint-Domingue’s astounding journey from a French sugar colony of nearly a half million enslaved to an independent black nation is a convoluted tale. With the slave uprising, the colony erupted into battles that fell along economic and racial fault lines. At one point there were as many as six factions warring at once, with alliances formed and dissolved in rapid succession between the various groups: rich white planters, poorer white laborers, French troops trying to restore order in the colony, the opportunistic armies of England and Spain, free persons of color (most of mixed-race ancestry, “mulattos”), and the enslaved majority with its own internal divisions between African and Creole born. During the long years of fighting, most sides at one point courted the rebel blacks with offers to arm and then to emancipate. A “born soldier,” Dessalines became known as a courageous fighter and a fear- and fealty-inspiring commander in his own right. He ascended rapidly through the ranks, becoming a key and indefatigable general under the famous Toussaint L’Ouverture, fighting for the royalist Spanish army, then for the French republican army fighting against the Spanish and British. In 1799, Toussaint entrusted Dessalines with putting down a civil war, which has been typically understood as a conflict between mulattos in the south against the blacks, who were aided by a U.S. Navy blockade. With the revolts crushed, Toussaint needed to stabilize the black armies and eliminate officers and soldiers loyal to his rival, the defeated southern leader Andre Rigaud. Dessalines’s reprisals led to many executions, to which Toussaint is said to have chastised, “I said to prune the tree, not to uproot it.” Some scholars have suggested, however, that Toussaint had ordered these killings but had his generals take responsibility in order to keep his hands and reputation (relatively) clean (James 236; Dubois 236). Regardless of the veracity of the claims of such political underworkings, the war’s events have allowed most histories to treat Dessalines as Toussaint’s brutal foil.

Nonetheless, Dessalines was the soldier that the battlefield and times necessitated, a general willing to see plainly what was needed and not hesitating to respond accordingly if bluntly. Military expediency, not diplomacy, distinguished Dessalines. After Toussaint’s capture and deportation in 1802, Dessalines deemed that the war was now a revolution for total independence rather than colonial autonomy with emancipation. And he succeeded in completing history’s most successful slave revolt, leading the colony to national independence, though Haiti’s subsequent instabilities have and continue to call into question how well this dream was achieved. Historian Laurent Dubois’s cogent assessment of Toussaint just as easily applies to Dessalines: “Though his ultimate inability to construct a multiracial, egalitarian, and democratic society in Saint-Domingue might strike us as particularly tragic, given his origins, this was a failure he shared with the leaders of every other postemancipation society in the Atlantic world” (174).

History and legend link Dessalines with several signal acts in the birth of this first modern independent black nation. In May 1803, he tore the white band from the French tricolour, uniting the blue and red in a new flag. This became the symbol of racial unity between blacks and people of color in the face of France’s final attempts to retake the colony through a desperate war of extermination (Dubois, 292-3). The symbol of the flag would later be made concrete in the nation’s 1805 inaugural constitution, which proclaimed that all citizens would henceforth be designated “black.”

Dessalines’s “indigenous army” and a growing coalition of guerilla fighters, aided by a yellow fever epidemic, decimated the remaining French forces, who ultimately surrendered in December, 1803. On January 1, 1804, Dessalines proclaimed national independence and severed colonial ties by replacing the name Saint Domingue with the Amer-Indian word Haiti (ayti). As Dubois has noted, the re-christening of the nation with its original Taino name attempted to symbolically disrupt centuries of European empire and brutality (299). More ominously, the declaration also chided the new black citizens for not fully avenging their dead by allowing some French planters to remain on the island. Later that spring, rhetoric moved to action. Convinced that the French who had remained in the colony in the hopes of reclaiming some of their land and property were already plotting to destabilize the young nation, Dessalines ordered their execution. Ignoring the hideous atrocities of France’s campaign of extermination at the close of the revolution, popular accounts describe Dessalines’s orders as a barbarous aberration. By ordering the remaining colonists’ doom, Dessalines sealed for Haiti a lasting reputation as a nightmare republic in the eyes of the greater white world.

Dessalines’s meteoric rise from abject slave to iron-fisted emperor willing to preserve his fledgling nation’s freedom by any means necessary seems only fit to engender an even more dramatic downfall. Dessalines’s despotism, draconian labor policies, and enforced land reform plans soon disillusioned the peasants, fair-skinned elite landowners, and military alike. On October 17, 1806, Dessalines’s soldiers ambushed their leader and rendered his body to pieces. Legends state that the madwoman Défilée, possibly Dessalines’s spurned lover and a sutler to his troops, gathered, buried, and guarded the emperor’s remains in a final act of restorative devotion.

At his death, Dessalines was both torn asunder and repaired. His complex legacy suffered a similar fate. Over two centuries of Haitian, European and U.S. American popular representations of Dessalines reconstruct this leader, though often by eliminating his contradictions, thus rendering his complex legacy piecemeal. Haiti’s revolutionary heroes, especially the black triumvirate of Toussaint L'Ouverture, Henri Christophe and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, are important not only in political histories but also cultural storytelling. And not surprisingly, their biographical narratives are often conflicting and depend greatly on who is enacting the telling. In this essay, I will examine some of the many ways that popular representations of Dessalines have shaped his legacy—politically, creatively and ritualistically. I will begin with an overview of representations of the demonic Dessalines, which continued into the twentieth century, particularly during the U.S. Occupation of Haiti. Next, I will outline how African-American writers in particular have recovered Dessalines as a dramatic and powerful black hero, though one unburdened from his more extreme actions. I will conclude my discussion with the Haitian folk religion of Vodou, which is one of the few spaces that recognizes and celebrates the contradictory nature of this mercurial figure.

Early Haitian histories with accounts of Dessalines largely do not appear until around the mid-nineteenth century, during the waning years of the Revolutionary generation and a growing economic divide that tended to fall along color distinctions. These written accounts were largely put forward by the economically and politically powerful educated mulatto elite who, perhaps not surprisingly, privileged mulatto revolutionary leaders like André Rigaud over black leaders like Dessalines and Christophe. Historian David Nicholls gives one of the most comprehensive meditations on the divide between racial and color identities within Haitian culture and its importance in the construction of its history for political purposes. He notes, “Mulatto historians developed a whole legend of the past, according to which the real heroes of Haitian independence were the mulatto leaders…. The black leaders were portrayed as either wicked or ignorant, and the legend was clearly designed to reinforce the subjugation of the masses and the hegemony of the mulatto elite” (11; see also 85-101).

These early Haitian historians who chose to demonize Dessalines found good company with an already established and ever increasing body of European and U.S. accounts that established the vocabulary and interpretive lens through which this founding father and all of Haiti would be judged: African savage, diabolical, inhuman, ferocious, base and sanguinary, cruel and brutal, vain and capricious, lustful and insatiable (Barskett; Chazotte; Dubroca, Franklin; Harvey). In his literary analysis of narratives of the Haitian Revolution, Matt Clavin argues that the ubiquitous published histories and biographies that circulated throughout the nineteenth-century trans-Atlantic world commodified the Haitian Revolution and its principal actors. This flood of writing captured the attention of and titillated a growing boom of readers in a competitive literary market. Clavin argues that this was accomplished through the use of standard literary techniques, especially the conventions of Gothic literature, such as crumbling and exotic scenery, characters seemingly outside the bounds of Enlightenment rationality, and, above all, descriptions of “indescribable” violent and brutal acts (14-29). Dessalines provided the most direct and titillating example of exotic barbarity, the Enlightenment turned on its head but corrected with the equally brutal downfall of the black emperor, an example of horrific history that far outpaced Gothic fiction and found an eager audience.

Not surprisingly, these numerous accounts of the Haitian Revolution can also be sorted based on the ideologies of their authors: abolitionist or pro-slavery. Abolitionist accounts tended to diminish the role of Dessalines in lieu of Toussaint L’Ouverture, who in turn was presented as gentle, educated, Christian and compromising. Captured and deported before the extremely brutal final revolutionary period, where both sides waged a desperate war of extermination, Toussaint as martyr could become a positive symbol of black potential and enlightened character. What the Abolitionists downplayed, the pro-slavery side sought to exploit: Dessalines’s killings, portrayed as the sanguinary finale of blacks’ mercurial treachery, served as the shining example of the disasters that awaited sudden and complete emancipation. Pierre Etienne [Peter Stephen] Chazotte, who claimed to be one of the few eyewitnesses to survive Dessalines’s ordered massacre of French whites in 1804, published an English translation of his experiences in 1840, based, as he claimed, on notes he had written during the events. His work was meant to discredit what he saw as the abolitionist lies particularly propagated by the English. For Chazotte, Dessalines was a mindless executioner, a puppet of the English Wilberforce Society (41, 48, 69). Over several detailed pages, Chazotte regaled his readers with his direct observations of the executions (46-51), adding voyeuristic passages of pathos for the killings in the night that he overheard but did not see from his guarded residence: “Cries of murder, defiance, despair, rage, and vociferations, intermixed with the groans and lamentations of the wounded and the dying, resounded through the whole place” (50). Chazotte used his narrative to produce a damning account of the English as the main force who spurred the barbaric yet simplistic blacks towards violence, while also concluding that this merely shows the imitative nature of all persons of African descent and that a modern self-rule was well beyond Haitians’ capabilities.

Building upon earlier descriptions like Chazotte’s, the British Minister Resident to Haiti Sir Spenser St. John wrote the most popular and widely circulated of nineteenth-century descriptions of Haiti’s history and religion, Haiti or the Black Republic (1884), a work intended to prove the inferiority of blacks, especially regarding self-government. According to St. John, although Dessalines had been a revolutionary hero, what truly “endears his memory to the Haytians” was his inaugural act of white massacre (77). St. John notes that Dessalines suspected that some of his generals, out of “interest or humanity,” may not have carried out his orders fully and took it upon himself to tour the country and “pitilessly massacred every French man, woman, or child that fell in his way.” St. John continued, “One can imagine the saturnalia of these liberated slaves enjoying the luxury of shedding the blood of those in whose presence they had formerly trembled; and this without danger; for what resistance could those helpless men, women, and children offer to their savage executioners?” (77) (St. John, however, did allow that more properly enlightened and educated Haitians were at least “in truth utterly ashamed of the conduct and civil administration of their national hero” (79).) St. John’s work remained highly influential into the twentieth century, becoming one of the most frequently cited sources behind early accounts justifying and supporting the U.S. military invasion and occupation of Haiti. Two days after the initial U.S. Marine invasion of what would become a nineteen-year occupation (1915-1934), the New York Times outlined the Black Republic’s “customs” of corruption, despotism, revolution, and assassination, noting that this has held true since Haiti’s founding father had ordered the massacre of the country’s remaining whites (“Latest Revolution” 8). By invoking the terrifying events of 1804, the New York Times assured its readers of the vital importance of a strong U.S. military presence in 1915.

Five years later and in direct response to damning revelations of the U.S. Occupation’s financial and military abuses, the December 1920 National Geographic Magazine defensively presented the benefits of occupation in a lavishly illustrated, three-article suite which cited St. John’s 1880s work frequently. British explorer and photographer Sir Harry Johnston contributed one of the articles, presenting a picturesque Haiti greatly improved under U.S. guidance. Johnston, however, takes issue with a few lingering details. In Port-au-Prince, Johnston describes the great expanse of the Champ de Mars: “In the middle of this open space is a preposterously vulgar statue of Dessalines, who is regarded as the national hero of Haiti, the people having, with typical ingratitude, put on one side the real great man of their history, the remarkable and noble-hearted Toussaint L'Ouverture” (“Haiti” 496). The monumental honoring of a monster, rather than the more beneficent and accommodating Toussaint, underscored the National Geographic’s presentation of Haitians, particularly the peasants who dared to resist their U.S. occupiers, as petulant children who neither appreciated what was good for them, nor showed proper gratitude or respect.

Importantly, the information within this article was gathered during Johnston’s six-month trip through the Caribbean and United States in 1908-9, before the U.S. occupied Haiti. The National Geographic, therefore, has shifted the meaning and context of Johnston’s text to coincide with a vision of Haiti as newly cleaned-up and “regenerated” by the United States. Originally publishing his findings in The Negro in the New World (1910), Johnston did note at that time the ugly nature of the statue of Dessalines on the Champ de Mars and called for its removal (177). Johnston described the massacring Dessalines to be an “abominable monster of cruelty” and an example of “the Negro at his very worst” (159). Additionally, he argued, “It is a disgrace to Haiti that amidst all her monuments, good, bad, and indifferent, none has been raised to commemorate the character and the achievements of Toussaint Louverture, whose record is one of the greatest hopes for the Negro race” (158-9, italics in original). Johnston’s pronouncement mirrors Englishman Hesketh Prichard’s lament of 1900 that Haitians have consciously selected the barbarous Dessalines over the noble (and probably not “full-blooded negro”) Toussaint for their national hero (279-80). For both authors, Toussaint is the exception that proves Dessalines’s bloody rule. Moreover, outside observers continued to be incredulous of contemporary Haitians’ choice of Dessalines as the country’s highest honored national hero, a sure indication of the faulty and incompetent progress of the black nation.

What these outside observers failed to acknowledge, however, was that the honoring of Dessalines had and continued to be rigorously deliberated by the Haitian elite. The beginnings of the official recovery of Dessalines began in the 1840s. As the revolutionary generation passed away, Dessalines’s legacy was rehabilitated enough to allow for a modest grave marker, and an even more modest pension for his aging widow. In 1861, Haitian newspapers heatedly debated a proposal for the creation of a monument to Dessalines. As historian David Nicholls has pointed out, Haitians chose sides in this “acute controversy” based on political and racial allegiances; blacks and those espousing a noiriste ideology supported the creation of the monument, while most mulattoes opposed it. The few supportive mulattoes carefully advocated honoring Dessalines the “liberator,” not Dessalines the “despot” (86). Not surprisingly, French diplomats in Haiti actively campaigned against a monument in honor of one who had killed so many French citizens. No major monument resulted from this debate. Perhaps more fitting, Haiti had a gunboat named after Dessalines long before any memorial.

Full and official state-sponsored recovery of Dessalines as the liberator of the Haitian people waited until the 1890s with President Florvil Hyppolite (1889-96), who had a French-made marble mausoleum erected, and more importantly, rhetorically linked himself to the revolutionary hero to strengthen his own political agendas (Brutus 246-65). Nord Alexis, president during the 1904 centennial, completed the recovery of Dessalines’s patriotic legacy by unveiling the national anthem, “La Dessalinienne,” and commissioning the leading Haitian sculptor of the day, Normil Charles, to create the Champ de Mars monument.

Dessalines’s statue and rehabilitated legacy continued to prove malleable. Posed high on a pedestal, Johnston’s photograph (c. 1908-9) shows Dessalines stepping stiffly forward and holding aloft a saber in his right hand, and a scabbard in the left, which Johnston identified as an excessive second sword (“Haiti” 496) [fig. 1]. Dessalines braces a painted metal national flag permanently unfurled with the national motto, “Liberty or Death!” and “To die rather than be under the domination of Power.”

Later 1920s photographs, taken at the height of the U.S. occupation, show the isolated Dessalines still dominating the great public space, but now with his painted flag removed. Perhaps the call to liberty at all cost did not sit comfortably with a foreign occupier and accommodating administration working to put down insurgency and dissent. Charles’s statue would soon succumb to a similar fate. Criticized for its “cold mask” which did not resemble the likeness more popularly accepted by this time as the emperor’s, the Haitian government later removed the 1904 Dessalines to the town hall of Gonaives (Brutus, II, 261).

While nearly every history outlines Dessalines’s fierce and brutal character, there are very few contemporary descriptions of what he physically looked like. ‘A short, stout Black,’ seems to be the most thorough description left and no likenesses taken from life have been authenticated (Heinl 126). Rather, a range of likenesses from nineteenth-century engravings abound, with a few becoming privileged, and one accepted as a correct representation by state-sponsored commissions in the twentieth century: the portrait of Dessalines from the series of paintings displayed in the national palace, Heros de l’independence d’Haiti (1804-1806) (fig. 2). Several Haitian administrations promoted this particular likeness of Dessalines and had it copied into medallions, engravings, and even a 1949 commemorative postage stamp by famed Haitian designer Louis Vergniaud Pierre-Noël. A new Dessalines monument now dominates Port-au-Prince’s Champ de Mars, this one created by famed African-American sculptor Richmond Barthé and installed in 1953. In this commission, Barthé worked directly from a photograph of the national palace painting.

All of these elite- and state-sanctioned images present a heroic black figure arrested in his grandeur, and not as a mercurial fighter and contested leader.

Perceptions of Dessalines’s character proved even more malleable than his image. Dessalines expected and embraced the fact that the greater world would find him horrific and blood thirsty. The January 1, 1804 declaration of independence was proclaimed before a crowd at Gonaïves. It is clear, however, that Dessalines and his secretary, an educated officer of color named Louis Félix Boisrond-Tonnerre who authored and read the proclamation on Dessalines’s behalf, understood the proclamation’s audience to include not only the new citizens of Haiti, but also the greater international community. The declaration rebukes Haiti’s new black citizens for failing to avenge their dead by allowing some French to still remain in the country. The elimination of these French would serve not only as the final step in completing the war of emancipation, it would also ensure that no remaining foreigner would continue to plot “to trouble and divide us” (Dubois and Garrigus 189). More importantly, Dessalines/Boisrond-Tonnerre prods that a final act of massacre would send the most dramatic message possible to dissuade France and any other power that this fledgling nation could ever be reclaimed for slavery: ‘…know that you have done nothing if you do not give the nations a terrible, but just example of the vengeance that must be wrought by a people proud to have recovered its liberty and jealous to maintain it. Let us frighten all those who would dare try to take it from us again; let us begin with the French. Let them tremble when they approach our coast, if not from the memory of those cruelties they perpetrated here, then from the terrible resolution that we will have made to put to death anyone born French whose profane foot soils the land of liberty (Dubois and Garrigus 189).

’ Importantly, in the declaration’s closing lines, Dessalines also claimed his own legacy: “Recall that my name horrifies all those who are slavers, and that tyrants and despots can only bring themselves to utter it when they curse the day I was born…” (Arthur and Dash 44). In April 1804, following the actual killings of the remaining French planters, Dessalines proclaimed: ‘‘We have rendered to these true cannibals, war for war, crime for crime, outrage for outrage. Yes, I have saved my country; I have avenged America. The avowal I make in the face of earth and heaven, constitutes my pride and my glory. Of what consequence to me is the opinion which contemporary and future generations will pronounce upon my conduct? I have performed my duty; I enjoy my own approbation: for me that is sufficient’ (Barskett 183). ’ Dessalines carefully posited his acts against a history of the French slave system notorious for its excessive cruelties, tortures and rapes, and he orchestrated the executions to be a signal to the greater world of an unrepentant blackness that grounded the newly created Haitian identity.

Amazingly, despite his extreme rhetoric and actions, Dessalines’s character lent itself not only to disparaging accounts, but also dramatic and even morally uplifting representations. Since there are few records of Dessalines’s own accounting of his thoughts and actions, his life has been used as a blank canvas for more romantic inscriptions. Indeed, given how he proclaimed his own legacy, Dessalines probably would have been shocked by the numerous representations that attempt to sanitize his legacy, especially those examples put forth by fellow blacks. Several prominent African-American writers have attempted to recover a revolutionary hero without the accrued weight of his harsher actions. In 1863, former slave William Wells Brown published The Black Man, a collection of biographical sketches designed to refute stereotypes of black inferiority. For Brown, the courageous Dessalines “was a bold and turbulent spirit, whose barbarous eloquence lay in expressive signs rather than in words” (111). Brown, however, does not describe Dessalines’s “expressive signs,” stating that enough historians have noted them, but without rightly considering the circumstances under which he lived and led.

Three decades later, African-American publisher and activist William Edgar Easton out-distanced Brown’s positive portrayal in his play Dessalines (1893). In the play, Dessalines awakens from his excessive brutality when he rescues his mulatto enemy’s sister, Clarisse, from a voodoo witch and then falls in love with her. The fair Clarisse converts Dessalines to Christianity and the play ends without even a hint of massacres or political despotism. In the play’s preface, Easton openly admits to taking factual liberties in creating a play that would highlight the rich possibilities of uplifting racial drama. Yet his preface also laments the lack of African Americans writing and staging black history, implying the importance of historical fact. Easton believes drama to be the perfect medium for teaching both history and moral virtue. He prefers ultimately, however, to skew history and reconstitute a sanitized Dessalines in order to fulfill the higher purposes of serious moral drama and race pride: “Let the critic with a charitable hand separate its [the play’s] history from romance and give the author the credit, at least, of seeking, in the way he knows best, to teach the truth, that ‘minds are not made captive by slavery’s chains, nor were men’s souls made for barter and trade’” (vii).

Indeed, the debut staging of Easton’s interpretation of Haiti’s history was actually about the visibility and control of African-American self-presentation. Dessalines’s debut has been called the “most note worthy African-American event” during the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, even though it did not actually occur on the fairgrounds or with Exposition sanctioning. Rather, it was produced privately at the Chicago Freiberg’s Opera House as a part of the African-American protest against the Exposition’s exclusion of African Americans in its planning and the rejection of many proposals for exhibits to display the accomplishments of African Americans (Hill and Hatch 88-9, 138-9). Dessalines, therefore, needed first and foremost to represent black heroic accomplishment, and not the gray zone of a complex and violent historical reality.

Prominent twentieth-century African-American writers continued Easton’s belief in racial uplift through black historical drama, with Haiti frequently providing exciting material and inspiring heroic figures. And like Easton before them, those who staged their work around Dessalines as their lead character did so by ignoring the more contradictory and violent aspects of his actions. For example, writer and linguist John Matheus wrote the libretto to the opera Ouanga: a Haitian Opera in Three Acts (c.1929; copyrighted 1938) centered on Dessalines’s 1804-1806 rule, but omitted his ordered killings. Rather, Ouanga portrays the emperor’s greatest crimes as forsaking his true love Défilée and attempting to outlaw voodoo, with both directly causing his assassination. Matheus preferred to have his romantic protagonist in dramatic confrontation with voodoo, rather than admit the terrorizing and tyrannical aspects of his hero.

Famed writer Langston Hughes also had an abiding fascination with Haiti, its revolutionary history, and the character of Dessalines. In February 1928, Hughes began work on an opera on the Haitian Revolution, first sketched as a “singing play” entitled Emperor of Haiti. His plot traces the rise and fall of a fierce Jean-Jacques Dessalines, whom he envisions as a key leader of the initial uprising. He revised his text into a play entitled Drums of Haiti, which was first performed in 1934; he continued to revise (and rename) the work, premiering Troubled Island in 1936. It was this later version that would be finally turned into an opera with music by William Grant Still, debuting in 1949 (Hughes Papers, boxes 536, 539; see also Rampersad 165-6, 175-9). Like Ouanga, Hughes’s play and opera dramatize the life and downfall of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and provide another example of a sanitized Dessalines as main character. Troubled Island begins on the eve of the revolutionary uprising in 1791. Act II then jumps forward over two decades to the end of Emperor Dessalines’s reign, thus omitting both the bloody fight for independence and Dessalines’s ordered massacres. While alluding to Dessalines’s military exploits, the heart of the later acts present Dessalines’s failures as a statesman, his rejection of the country’s African roots in voodoo, and his assassination as a betrayal by his treacherous mulatto assistants and consort.

In one final example of Dessalines’s extreme sanitization at the hands of African-American writers, Helen Webb Harris composed Genifrede: The Daughter of L’Ouverture, a Play in One Act (1923) as part of a drama class at Howard University. In her example, Harris centers the play around the iron-will of Toussaint L'Ouverture, but presents Dessalines as a moderator to Toussaint’s extreme sense of justice, which included executing his daughter’s fiancé. All of these productions present the Haitian revolutionary as a figure of heroic black masculinity, reflecting an African-American focus on representational figures to instill race pride.

These African-American writers portrayed Dessalines as a simplified and somewhat thuggish saint. Interestingly, within the Haitian folk religion of Vodou, Dessalines actually has become a saint. Vodou is a highly syncretic, African-derived, complex New World religion that has vibrantly adapted (and continues to adapt) to the needs and struggles of Haitians. Like Dessalines, this much maligned religion has been distilled in the popular imagination outside of Haiti in the form of a highly circumscribed stereotype. The religion is known more popularly by the moniker “voodoo”; histories, sensationalized travelogues, and, especially, horror films present “voodoo” as a demonic, brutal, and blood- and zombie-driven cult of death and debauchery. While many Haitians believe in a single supreme God, they also believe in a pantheon of intermediary spirit-saints, or lwas, who actually intercede within their lives through personal encounter. Vodou’s dominant spirit and warrior is Ogou. Within the Vodou pantheon, Ogou splits into multiple manifestations, creating a family of spirits tied to war and, since the army is never far removed from government in Haiti, politics and social power. Vodou’s adaptability means that new historical events and leaders can be incorporated into this divine army. The historic Jean-Jacques Dessalines, like most elite blacks and mulattos of his era, probably opposed and even worked to suppress Vodou (Nicholls 170). In death, however, Haitian adherents incorporated him into the Vodou pantheon as Ogou Desalin. Like his historical counterpart, Ogou Desalin is a powerful guardian and fierce conqueror. He is also vainglorious with a notorious sexual appetite, a penchant for blind rage, and an equivocal nature (Dayan 139; Largey 328).

Vodou rituals involve what religious scholar Karen McCarthy Brown has termed “performance-possession”: the dramatic moment when a Vodou spirit possesses (or mounts) an adherent (Mama Lola 6). Through the possessed individual, the lwa bodily displays his personality, and interacts with those present at the ceremony. His physical likeness shifts, therefore, with each person possessed, transcending the visual representations of Dessalines codified by the state’s various commemorative and political projects. In Haiti’s highly visual and oral culture, such ritual performances become bodily manifestations where past histories meet present problems, helping to create meaning and solutions.

All manifestations of Ogou poignantly model the constructive and destructive uses of power. Brown has described the ritual dance performed by those possessed by Ogou. First, Ogou takes a ritual sword and wields it against an invisible enemy. Before long, however, his aggressive swipes and jabs become directed towards people present at the ceremony. Finally, Ogou turns the sword upon himself. Ogou performs the paradox at the center of Haitian military and political history, where leaders heralded as heroes have time and again turned upon their own people while also instigating their own destruction (Mama Lola 95-6). Dessalines proclaimed himself the avenger of the former slaves, yet he considered his people ungrateful and unruly, and used his standing army to enforce draconian labor policies. In establishing a national identity centered on blackness and land ownership, Dessalines also threatened the fairer-skinned elite, contributing to his assassination.

Historian Joan Dayan has provided one of the most extensive analyses of Dessalines’s leap from revolutionary leader to lwa. Kreyol folk and ritualistic songs, which may be as old as the revolutionary era, focus on the liberty that Dessalines brings, yet through a body that is both powerful and dismembered, heroic and corrupt, living and dead. The songs’ Kreyol words embody multiple meanings and necessarily duplicitous, interpretations. Likewise, in Vodou ritual, when Ogou possesses an adherent and makes himself manifest to worshippers, his ritualistic actions and pronouncements are also duplicitous, revealing both his multiple nature and the contradictions inherent within power structures: ritualistic actions show both devotion and vengeance, efficacy and blind rage railing against insurmountable odds (Dayan 31). As we have seen, and much to the chagrin of nineteenth- and twentieth-century outside observers, many Haitians claim Dessalines as their most revered national hero despite his dramatic faults. Perhaps this is because Dessalines goes beyond his fighting for and founding of independence; now as Ogou Desalin, he both resists oppression and displays how power can corrupt. This is a prescient model for understanding the personal and political injustices found within the adherent’s contemporary world.

Within Vodou, remembered histories possess the power to shape and interact with contemporary problems. The worship of Ogou Desalin performs an important revolutionary history and embodies contemporary relationships with power structures. Ogou Desalin shows that liberation is never complete, while teaching that the most powerful can be the most vulnerable and vice versa. Ogou Desalin also shows that power in general is always corruptible, and that the dispossessed must always be wary of whom they call hero. Rendered to pieces at his death, Dessalines’s spirit and legacy has only grown more powerful as representations continuously reconstitute, rework and repair this mercurial hero. Most popular representations circumscribe him to the space of either demon or saint. Vodou, however, provides a model that accepts and even finds necessary Dessalines’s equivocal nature.

*Acknowledgments: Initial research that led to this article was made possible through the support of the Henry Luce Foundation/American Council of Learned Societies’ Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship in American Art, 2004-2005 and was presented at the College Art Association Annual Conference in 2006. Research for its completion was enabled by support from the Augustana Research and Artist Fund of Augustana College, Sioux Falls, SD, and an A. Bartlett Giamatti Fellowship from the Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

Works cited

- Arthur, Charles, Michael Dash (eds.) A Haiti Anthology: Libète 1999. London: Latin American Bureau.

- History of the Island of St. Domingo: from Its First Discovery by Columbus to the Present Period 1818. London: Frank Cass.

- Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn 1991. Berkeley: University of California.

- “Systematic Remembering, Systematic Forgetting: Ogou in Haiti” Africa's Ogun: Old World and New Sandra Barnes (ed.) 1989. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 75; 78.

- The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements 1863. Boston: James Redpath. 1969. New York: Kraus Reprint Co..

- L’Homme D’Airain: etude monographique sur Jean-Jacques Dessalines fondateur de la nation haitienne; histoire de la vie d’un esclave devenu empereur jusqu’a sa mort, le 17 Octobre 1806 2 Vols. 1947. Port-au-Prince: Imprimerie de l’Etat.

- Historical Sketches of the Revolutions, and the foreign and Civil Wars in the Island of St. Domingo, with a Narrative of the Entire Massacre of the White Population of the Island New York: WM. Applegate, 1840.

- “Race, Rebellion, and the Gothic: Inventing the Haitian Revolution” Early American Studies (Spring 2007) pp. 1-29.

- The Present State of Hayti 1828. London: John Murray. 1970. Westport: Negro Universities Press.

- Haiti, History and the Gods 1995. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution 2005: Harvard University Press.

- Slave Revolution in the Caribbean 1789-1804: A Brief History with Documents 2006. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s.

- Vida de J. J. Dessalines, gefe de los negros de Santo Domingo. D. M. G. C. (ed.) 1806. Mexico: Zuniga y Ontiveros.

- Dessalines: A Dramatic Tale (A Single Chapter From Haiti’s History) 1893. J. W. Burson-Company, Publishers.

- Sketches of Hayti: from the Expulsion of the French to the Death of Christophe 1827. 1971. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd..

- Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492-1971 1978. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 2nd ed. rev by Michael Heinl (ed.) 1996. Lanham: University Press of America.

- A History of African American Theatre 2003. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Emperor of HaitiBlack Heroes: Seven Plays Errol Hill (ed.) 1989. New York: Applause Theatre Book Publishers.

-

Langston Hughes Papers. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution 1938. Second Edition. 1989. New York: Vintage Books.

- “Haiti, the Home of Twin Republics” National Geographic (December, 1920). vol. 38.6 pp. 483-96.

- The Negro in the New World 1910. 1969. New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation.

- “Recombinant Mythology and the Alchemy of Memory: Occide Jeanty, Ogou, and Jean-Jacques Dessalines in Haiti” Journal of American Folklore (Summer 2005). vol. 118.469 pp. 327-53.

- “The Latest Revolution in Haiti” New York Times 29 July 1915. pp. 8.

- Ouanga: a Haitian Opera in Three Acts

- From Dessalines to Duvalier: Race, Colour and National Independence in Haiti 1996. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Where Black Rules White 1900. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- The Life of Langston Hughes, 1902-1941: I, Too, Sing America 1986. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hayti or The Black Republic 2nd ed. 1889. New York: Scribner & Welford.

List of Images

Fig. 1 Normil Charles, The Statue to Dessalines on the Champ de Mars, Port-au-Prince, 1904. Photograph by Sir Harry Johnston, c. 1908-09. First published in Sir Harry Johnston, The Negro in the New World (London: 1910); reprinted unattributed, Statue of Dessalines, Erected 1904 in Anonymous, Wards of the United States: Notes on What Our Country is Doing for Santo Domingo, Nicaragua, and Haiti, National Geographic Magazine 30 (August 1916): 173. Photograph available through the New York Public Library Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Fig. 2 Anonymous, General Jean-Jacques Dessalines (1758-1806), from series: Heros de l’independence d’Haiti (1804-1806), painting in the National Palace, Port-au-Prince. Published through Haitian tourist bureau, special issue: Tricinquantenaire de l’Indépendance d’Haïti, Formes et Couleurs 12.1 (1954). W. E. B. Du Bois Collection, Special Collections Fisk University, Nashville. Photograph available through the New York Public Library Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.