Listening for Noise

For those of us who study and teach the literature of slavery and abolition, listening for silences as attentively as voices is a matter of ethical urgency. Since the publication of Gayatri Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?” (1988), critics who write about the colonial and postcolonial world have been faced with the challenge of listening beyond voice, which, in the texts we tend to teach, is so essentially constructed by and for the Western subject. The problem with voice is its privilege—only few can speak, and even fewer are actually heard. Silence too poses its own interpretive challenges. We find the critical limitations of silence in Edward Said’s well-known interrogation of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (1814), a novel that notoriously dials down the volume on the subject of slavery and empire that haunts its geographic and fictional borders. Critics have taken turns defending Austen’s evident reserve on the slavery question in the novel.

Many have insisted that, if it is silent, Austen’s novel faithfully captures the taboo nature of the theme in its own historical context and assumes an implicit contemporary understanding of and sensitivity to the moral crisis at the center of the Bertram estate.

More recently, however, Lynn Festa has proposed that in Mansfield Park Austen may not be asking us to listen for the omissions that fill the novel’s silences so much as urging us to listen for what its noise might tell us: “For we may hear but we do not usually listen to noise. . . . For who listens to noise? We moderns consider having a voice as fundamental to social and political representation, and silence is often equated with oppression” (152, 154). As Festa distinguishes here, listening for noise means paying attention to sounds we would otherwise block out because they are too raucous, inarticulate, or inconvenient. And in Mansfield Park, many things are noisy—the urbane Crawfords, the staging of Lover’s Vows, and, of course, Fanny Price’s questions about the slave trade at the dinner table. Though Fanny’s timid inquiries about slavery threaten to disrupt the tranquility of Mansfield Park, they hardly amount to the kind of political voice that Spivak problematizes, nor do they qualify as silence within the terms of Said’s famous critique, even if she is in fact silenced. If Fanny’s questions fall on deaf ears, it is not because they do not echo in the room but because they travel at an inconvenient frequency. “When Austen asks us to hear noise,” Festa observes, “she is asking us to recognize that noise is not simply what needs to be blocked out to hear the ‘real’ message, like the static that makes the radio hard to hear. It may be something—in this respect, noise is like Fanny—that we need to listen for” (153). In other words, listening for noise means being alert to the static in the soundscape of the imperial world that so often escapes representation. Pondering the marked noisiness of Mansfield Park, Festa concludes that Austen implores us to open our ears to precisely this kind of imperial static.

In this essay I propose that we accept Festa’s invitation to listen for noise in the literature of slavery and abolition in the Atlantic world. Instead of attending to fiction, however, I invite us to listen to the poetry that fills the archive. Poetry is obviously rich in sound—meter, rhyme, alliteration, and so forth—but its noise, as Festa has defined it, is not always something that is heard or listened for. Fortunately for us, the archive of slavery contains plenty of poetry, primarily because abolitionists understood verse as a powerful medium that arouses the moral sentiments. One of the most popular forms embraced by antislavery poets was the ballad, a poetic genre that is particularly noisy because it reverberates a national history and an oral tradition that is only rarely attended to. While balladeers construct a voice (or voices) in their ballads, other historical noises haunt the form, including a musical tradition. When I teach ballads by abolitionist poets like William Cowper and Hannah More in my classroom, I begin by asking my students to examine the formal and rhetorical strategies that these white writers used to construct enslaved Black voices. Part of this exercise, however, requires that we listen beyond the constructed voice found on the surface of the poem to the musical history that today only comes through as static, or, as Festa proposes, as noise. Rarely do teachers of poetry pay attention to ballad tune (or melody) but doing so can sometimes help clarify the political stakes of a poem. In Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” (1788) and More’s “The Sorrows of Yamba” (1797), this musical dimension allows us to access a British imperial history through a melody that enriches our political sense of these poems. For contemporaries of Cowper and More, old ballad tunes might affect listeners given their own familiarity with national songs, but for today’s readers of poetry tunes are more often than not meaningless static. In what follows I consider the ballad’s media history as a kind of meaningful noise that, in the context of British slavery and abolition, raises important questions about the limits of political representation and voice for enslaved subjects.

I teach eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century British antislavery ballads alongside M. NourbeSe Philip’s astounding collection of poems, Zong! (2008), which taps into a related but altogether distinct form of static—the noise in the law. Philip’s title refers to the infamous eighteenth-century slave ship that became the subject of a horrific and historic British legal case, Gregson v. Gilbert (1783). The Zong witnessed the intentional mass drowning of over one hundred enslaved Africans in order to claim an insurance policy on its human cargo, a great fraction of which had become sick at sea from disease or malnourishment. When the insurance company refused to pay out the claim on the Zong’s enslaved cargo, William Gregson and his syndicate brought the case to trial. While technically tried as a disagreement about an insurance policy, the case opened up a host of ethical questions regarding the treatment of the enslaved at sea. The chief justice, Lord Mansfield, who presided over several landmark cases devoted to the slave trade, ultimately ruled against the owners of the Zong on a technicality—evidence arose in the ship’s log that rainfall had ameliorated the water shortage that Gregson and his crew claimed made the cargo disposable. Philip’s extraordinary project in Zong! is to listen for the noise of slavery in the legal documents of Gregson v. Gilbert and to reconstruct poems using only that language to offer testimony that was inadmissible at the time of the trial, testimony that could only be dismissed as legal noise. My aim in pairing antislavery and contemporary poems in this class is to underscore the precarity of political voice in the slavery archive. To this end I engage my students in a conversation about the limits of poetic justice in verse about transatlantic slavery by uncovering the profound historical and interpretive potential of what I have outlined here as noise.

II. Ballad Noise

The task of listening for noise in antislavery ballads is perhaps more challenging than in a study of fiction because, of course, poetry is so noisy. At the same time, critics and teachers of poetry are used to being attentive to sounds that students or lay readers may not listen for. Beyond listening to narrative or voice in poetry, there is also meter, rhythm, rhyme, and alliteration, frequent topics of discussion in any class on poetry. In the case of the ballad, however, there is also tune. Music is often overlooked because the literary study of the ballad tradition since the nineteenth century deprioritized tune in favor of qualities like lyric voice, a shift that all but rendered tune an inconsequential noise. Prior to the nineteenth century, however, printed ballads were understood as lyrics accompanied by a musical score that functioned as a deeply meaningful dimension to any ballad. Music works on us in a way that precedes cognition and can possess us like a spirit from without. In the ballad tradition tunes were recycled for new poems, which meant that modern ballads often carried a tune from a much older song. This detail in the ballad’s media history places the genre in a special category in the poetic tradition because ballads carry a musical past that is now commonly ignored as noise.

Two canonical eighteenth-century antislavery ballads carry an old tune that we should listen for: Cowper’s “The Negro’s Complaint” and More’s “The Sorrows of Yamba.” The old song these poems echo is Richard Glover’s “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” (1740), a naval ballad written during the Walpole era that celebrates a military victory in the Spanish West Indies and mourns the tragic and avoidable loss of thousands of English sailors to yellow fever on those waters. In Glover’s political ballad, the ghosts of these sailors call out to the reader or listener to be remembered for their service and sacrifice. In my classroom I invite my students to listen to Glover’s song, and I ask them what it might mean that the enslaved Black voices constructed by Cowper and More are mediated and amplified by a tune about thousands of white English sailors who perished at sea. Why would Cowper and More make such a formal decision? And what are some of the challenges that this decision poses for the political and literary representation of enslaved Africans during the abolition debate? In other words, I ask how we might read “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” as a kind of meaningful noise.

All of these questions stem from a common problem—mediation. Fortunately for us, the thematic ghostliness of Glover’s ballad allows us to bring all of the ways in which mediation is in play into clear focus. The most obvious starting point is thinking about the ballad as a poetic medium, not only in terms of the layered musical and lyrical richness I’ve already described but also as an oral form that migrated into print culture in the late eighteenth century as collections like Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765) were assembled. In fact, Percy included Glover’s “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” in his popular compendium of national songs. As Celeste Langan and Maureen McLane have observed, poets of Cowper’s generation participated in finding a middle ground between oral and printed ballad forms in crafting new ballads during a period of media transition (242). Indeed, Cowper and More are members of the last generation of poets that seriously and intentionally engage the musical dimension of the ballad.

Another way to think about mediation in these poems is in spiritual terms. Mediums, after all, are those persons who channel spirits from another world to our own. In “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost,” Glover performs the task of giving voice to the sailors haunting that poem. In the later antislavery ballads that carry its tune, the enslaved speakers function as another kind of medium altogether in their reverberation of the older naval song. These enslaved subjects both echo and jar against the voices of the sailors in Glover’s poem because their historical situations couldn’t be more different.

Further still, Cowper and More act as mediums for both the Black voices they represent and the ghosts of Glover’s ballad. When I present the layered and haunted quality of these ballads in my classroom, my students are often surprised and provoked by the racial complexity of the voices they hear—the enslaved African speakers are politically mediated by both white poets and the spirits of white British sailors.

Understanding these layers, they are more fully aware of the rhetorical strategies and stakes involved in the ballad form in the abolition context.

What becomes clear in this triad of ballads is that haunting is both formal and political. “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” functions as a kind of historical white noise resounding in the later soundscapes of “The Negro’s Complaint” and “The Sorrows of Yamba.” In media studies, the term white noise refers to static that exceeds the intended signal or message being transmitted. In the antislavery ballad tradition, I’m interested in thinking not only about music or tune as white noise in academic studies of the ballad but also in the racial implications of this music—the whiteness of the voices amplifying Black, enslaved speakers. Beyond this ghostly musical mediation, these poems also exhibit a kind of possession that is intrinsic to the ballad form. As Susan Stewart argues in her essay “Lyric Possession,” poets who write ballads are implicitly possessed by a national history as they broadcast an oral tradition in their revision of older songs. “Of all the singers of Western lyric,” Stewart writes, “the ballad singer is the one most radically haunted by others, for he or she presents the gestures, the symptoms, of a range of social actors, and he or she presents those gestures as symptoms of a previous action” (41). In other words, haunting is a formal process native to the very composition of ballads. The poet functions as a medium for historical action in their embodied composition of a new song according to an older musical and metrical schema. Stewart calls this “the submersion of will within convention” (40). In the poems we are dealing with, however, possession is just as political as it is formal insofar as they condemn an institution that supports the deprivation of human will. Bound by the formal imperatives of the ballad tradition, Cowper and More become strange mediums and precarious political representatives in their attempts to embody the experience of enslaved persons while conjuring a formal and national history. Moreover, the voices we find ringing in the ballads form a strange and spectral chorus of competing political pleas.

As scholars like Simon Gikandi, Laura Doyle, and Ian Baucom argue, the archive of Atlantic slavery is hauntological and generically marked by the gothic. One of the Afro-Caribbean spiritual practices that I share with my students in our discussion of lyric possession is obeah, a common ritual among early slave communities in the West Indies. As Alan Richardson reveals in “Romantic Voodoo,” obeah was a slave practice that struck fear among the British in the Caribbean and in England after it began to appear in popular fiction and poetry in the late eighteenth century, as we find in William Earle’s sensational novel about obeah and the Jamaican folk hero Jack Mansong, Obi; or, The History of Three-Fingered Jack (1800).

Accounts of obeah rituals also filled popular histories of the West Indies, including Edward Long’s History of Jamaica (1774). These representations amplified colonial anxiety in the wake of slave rebellions in the West Indies and exacerbated national tensions generated by political revolutions in France, Haiti, and America. For our purposes, however, obeah might be considered as one form of imperial noise that echoed within British cultural production about slavery at this time. In its investment in ritual and incantation, we might also think about obeah as an Afro-Caribbean analogue to lyric possession, as we see in William Shepherd’s “The Negro Incantation” (1797). In this poem, Shepherd parrots an obi priest via the ode form as he calls for “the white man’s doom” by spurring a slave insurgency using material rituals and lyric conjuring:

If the lyric possession we find in ballads by Cowper and More summons the specters of British imperial history through music, Shepherd invokes the spirit of obeah to craft a political ode designed to raise alarm about racial and imperial tensions in the West Indies. Discussing obeah alongside M. NourbeSe Philip’s own incantatory poetics raises fascinating questions about the limits of Western poetic forms like the ballad or the ode when framing historical Black voices. As Philip argues in her essay “Notanda” (included in Zong!), the project of rescuing enslaved Black voices from the history of British law required a poetic approach that exceeded the rationality of Western forms. The poems generated by Philip’s “irrational” approach to historical texts seem to echo the radical shamanistic practice of obeah in colonial life in ways that feel historically authentic and politically effective. Form, Philip teaches us, can sometimes speak so loudly as to drown out the voices that poetry is meant to broadcast. I will return to obeah in the next section.

By reading British antislavery and naval ballads together with my students, I aim to accomplish several things. First, I demonstrate how a Black voice is constructed in an antislavery ballad and generate discussion around the politics of that construction with special attention to the rhetoric of voice in each poem. Second, I teach my students about ballad form and its media history, including the element of music so often overlooked in the study of the ballad. Next, I share the political history of Glover’s “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” and comment on how it intersects with British transatlantic slavery. My goal at the end of these exercises is to invite students to think critically about what it means for Cowper and More to have chosen Glover’s song as a tune and a spirit for the voices of enslaved Black subjects in their poems.

My approach to these complex poems in the classroom is first to invite my students to close-read Cowper’s and More’s ballads together while paying close attention to voice. Whose voice(s) are we hearing? And, who is listening? I remind them that these are lyric poems by white English writers who construct an African subject and voice for an English audience. Our first exercise is to deconstruct that voice to understand the rhetorical strategies at work in the two poems, which are distinct in both message and approach. We find that Cowper’s African speaker makes a rational plea for liberation and challenges the reader to examine his or her own sense of justice in the face of the appeal. More’s Yamba, on the other hand, offers a much more sentimental and sympathetic voice whose tragic story is designed to appeal to our moral feelings. Moreover, Yamba echoes an Evangelical narrative in her turning to a missionary to find solace in a Christian life and its teachings. To shed light on each poet’s rhetorical strategy, I offer up biographical details about Cowper and More that give us some insight, including Cowper’s religious mania and isolation and More’s commitment to practical and religious teachings for the working-class public in writings like the Cheap Repository Tracts series (where “Yamba” appeared). These biographical details help students understand that there are personal traces of Cowper and More in the Black voices they construct

One of the awkward attunements we find in More’s poem is that it displays an attempt at Afro-Caribbean dialect. This is common among ballads in the abolition archive and significant because ballads must also adhere to the genre’s metrical patterns. What does it mean, I ask my students, that poets attempted dialect while at the same time accommodating the voice to English ballad meter? Finally, I contextualize the poems in the wider historical landscape, pointing out that More’s poem was composed after the beginning of the French and Haitian revolutions, which may account for its more conservative tone and narrative. I often generate discussion around the political efficacy of each ballad by asking students to compare their strengths and weaknesses.

Because these poems were distributed as broadsides and our attention is on ballad media, I share images of both broadsides with my students. As popular forms, broadsides were inexpensive literature and news media that circulated widely in town centers (coffee houses and taverns, for example) and eventually migrated out into the country. As the historian of abolition Brycchan Carey has shown, a ballad reproduced on broadsheets could circulate rapidly, particularly if the ballad was set to a recognizable form and tune (100). Abolitionists working with the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade understood the importance of inexpensive print materials as they sought to reach a wide popular audience, and the broadside was an ideal vehicle for their message. The broadsides printed for Cowper’s and More’s ballads usually advertised “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” as the tune for their poems underneath the title. Glover’s song was a popular tune that one might hear played in an eighteenth-century drawing room, and so I make sure to play a recording of the song, accessible to everyone on YouTube (Craig), in my classroom. The purpose of this demonstration is to immerse my students in the ballad’s media history. In the past I have even printed the ballads on single sheets so that students might read the poems as the tune plays. Once students hear the tune, they are immediately struck by the awkwardness of framing an enslaved voice in the tunes and metrical frameworks of polite society. A productive conversation can emerge from reflecting on the aesthetic effects of these formal choices when students are reminded of the intended British audience and the sensitive political debate around slavery happening at the time. In order for the British public to connect and sympathize with an enslaved African subject, that subject needed to sound as British as possible.

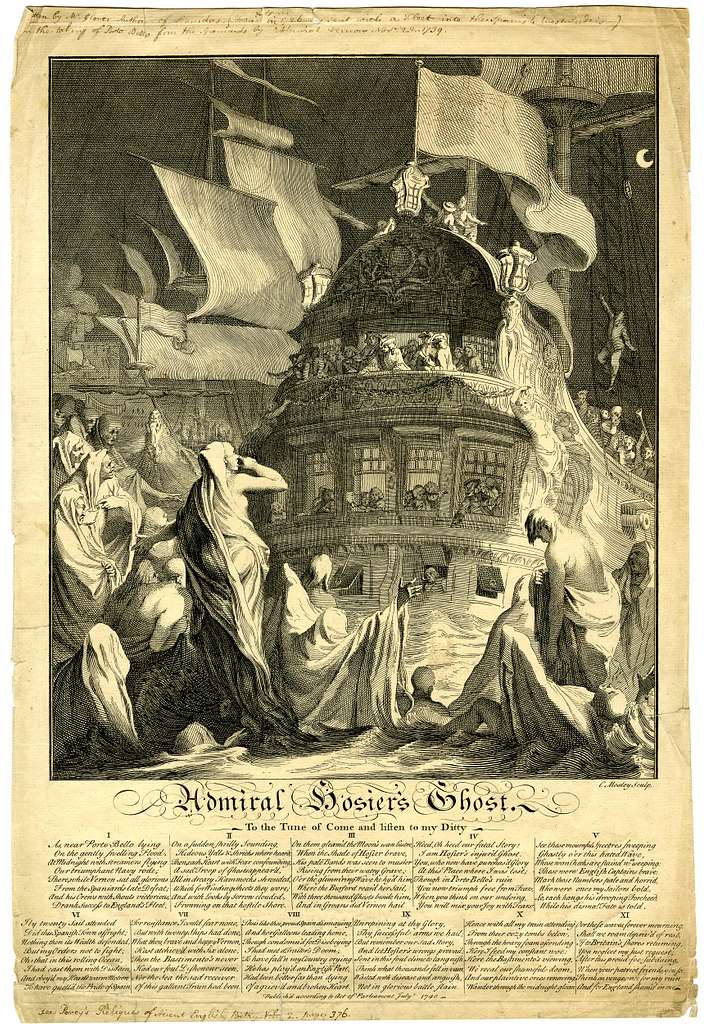

Next, we turn to the broadside for “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost,” which features a striking political cartoon of maritime specters rising from the Caribbean Sea. I offer my students an account of the dynamic political climate surrounding Glover’s poem and some details about Glover himself. Descended from the merchant class in London, Glover supported the financial interests of trading companies that trafficked across the Atlantic, including companies that bought and sold African slaves (Baines). In the early eighteenth century, British trading vessels were routinely attacked and raided by Spanish ships. Because Robert Walpole was reluctant to go to war with Spain at this time, London merchants heavily criticized his lack of aggression against Spanish interference in the West Indies (Rodger 234). When Walpole sent Vice-Admiral Francis Hosier and his fleet to conduct a blockade along the mosquito-infested waters off Porto Bello, a Spanish settlement in what is now Panama, in 1726, over three thousand sailors contracted yellow fever and died. Seeing his opportunity to criticize Walpole, Glover drafted “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” to remind the British public of the fatal consequences of Walpole’s refusal simply to overtake the Spanish port. In the poem, Hosier’s spirit rises from the waters near Porto Bello to relate his melancholy tale to Admiral Edward Vernon, who successfully sacked Porto Bello twelve years later, in 1739. The ballad thus mourns the lives of the sailors lost at Porto Bello due to Walpole’s military failure, while celebrating Vernon’s later victory for Britain.

Figure 1. "Admiral Hosier's Ghost" by Richard Glover (1740), colored etching by C. Mosley (1740), National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

In “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost,” Glover’s strategy is to exhume recent history from the sea for political purposes, which is also the strategy employed by Cowper and More in their later antislavery ballads. When we read the poem in the classroom, I ask students to consider the dead sailors’ spectral plea to be remembered for their sacrifice in the midst of imperial triumph. Hosier’s ghost rises from the waters and addresses the victorious Vernon on behalf of his crew:

I ask my students to think about what this plea for remembrance means when the tune of Glover’s poem transfers the sentiment to the tongue of the enslaved speaker in Cowper’s and More’s later ballads. As a way to think through this question, I offer more historical context on Porto Bello. In the early eighteenth century, Porto Bello was a major Spanish outpost for the slave trade, and historians reveal that many slaves in the region suffered and died of the very yellow fever that claimed Hosier and his men (Lohse 74–109). While it is not at all surprising that these African voices are not heard in Glover’s ballad, it is significant that Cowper and More later give voice to their own enslaved speakers by echoing, at least musically, the voices of the sailors from that original ballad. In other words, the noise of slavery ringing in Porto Bello was muted in Glover’s ballad and only becomes audible in the antislavery ballads that recycle its tune decades later. One other important detail to emphasize in discussing the poem is that while Glover’s song is elegiac in tone, it actually celebrates Vernon’s victory and imperial expansion in the Caribbean and implicitly supports the trading interests of companies trafficking in enslaved bodies at that time. In this light, “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” seems out of tune with the political message of the later antislavery ballads that echo its music. Discussing Cowper’s and More’s potential motivation for this awkward decision with students is a generative exercise. While the melancholy tone and maritime context certainly seem appropriate, the actual politics of Glover’s song—the zeal for the expansion of empire—seems dissonant with that of the antislavery lyrics. One explanation that may be offered is that the poets sought to reform the imperial economic impulse of Glover’s song by purging it of the moral stain of slavery and overwriting its voices with those of the disenfranchised.

Coming back to the question of voice can help students understand the real limitations of political sympathy in this context. Whose voice(s) do we hear in these poems, and why does it matter? The white noise we hear in antislavery ballads by Cowper and More is, after all, the spectral chorus of Glover’s song. It is likely that these poets chose Glover’s tune to strengthen sympathy for their enslaved African subjects. However, as Saidiya Hartman has proposed in Scenes of Subjection (1997), sympathy in the literature of slavery and abolition can be as destructive a mechanism as it is humanizing. While we typically understand sympathy as our best means of human connection, it can often obliterate otherness in the process because it “fails to expand the space of the other and merely places the self in its stead” (20). The abolitionist project is often criticized for the ways in which the literature it produced whitewashed its enslaved African subjects, a transformation that seemed necessary for political reform at the time. Choosing Glover’s tune for their ballads, Cowper and More hoped to tap into a well of melancholy about the loss of English sailors during a major event in English imperial history. In doing so, they sought to facilitate as much sympathy as possible, but that mediation certainly comes at the cost of an authentic encounter with human otherness. To encounter otherness more directly would require a recognition of the limitations of sympathy, given our own national, racial, and gendered identity. It would also require an understanding of the limitations of the British abolitionist archive, which might be supplemented by West African or Caribbean texts that may have seemed alien to the British public—and particularly genres less mediated by abolitionist leaders, such as African music and song.

Another complication with respect to sympathy is the difference in situation between an encounter with one voice as opposed to many. While it seems natural to feel a more powerful sympathy for an individual, these sonically layered poems do in fact conjure a chorus of voices. Philip’s contemporary poetry collection Zong! develops this problem by refusing to construct individual voices altogether. Instead, her poems about slavery are fragments of voices rescued from the language of history and the law. White noise thus forms the polyphonic text of the Zong! collection, allowing Philip to foreground the absence of enslaved voices in the archive while preserving the language of Gregson v. Gilbert. Engaging these cacophonous and irrational poems, sympathy seems impossible and perhaps beside the point. In Zong! Philip transforms the noise in the law surrounding the horrific Zong massacre into a kind of poetry whose aim is not to generate sympathy but to stage an ethical encounter with the victims of history that is as irrational as the event itself.

III. Listening for Noise in the Law

I ask my students to think about noise and formal haunting in a slightly different way when we turn to Philip’s Zong! collection, which was inspired by a similar scene and situation. Both the Zong massacre and the deadly plague in Porto Bello featured in “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” are tragic and melancholy episodes in British imperial history. However, Philip’s poetic approach to history is vastly different from that of Cowper and More. As an Afro-Canadian attorney as well as a poet, Philip’s shared interests in the history of transatlantic slavery and the law drew her to the Zong massacre. Philip’s project in Zong! is to listen to the noise in the legal documents of Gregson v. Gilbert and to make that noise available to readers as poetic language. This involves mutilating the text of Lord Mansfield’s decision in that case and using it as a repository of language to reconstitute traces of the voices of the enslaved muzzled by the legal proceedings. While Mansfield famously expressed personal disgust with the institution of slavery, the conventions of the law prevented him from writing a decision that recognized the enslaved Africans in question as legal or political subjects. Part of Philip’s challenge in Zong!, then, is to use that same language to attempt to give voice and reconstitute subjectivity, even if only in a fragmentary way.

Understanding that the task of mediating individual voices is impossible and perhaps ethically problematic, Philip allows testimony to come through as linguistic noise. We might say she is attempting to reconstruct historical subjectivity as noise. In “Notanda,” she explains her process and tracks her difficult journey making sense of the case. She begins with this statement: “There is no telling this story; it must be told” (189). What she means is that to render the story of the Zong in poetic narrative would be impossible because it absolutely resists narration. And yet, it must be told. The problem as Philip sees it is that the horrors of the Zong massacre resist logic and rationality, and no sense could possibly be made from a mere accounting of the details of the story or from listening to any one historical perspective. Her solution is to commit herself to the irrational because the event itself was irrational. Only by “not-telling,” then, can the story be told. The “not-telling” involves fragmenting the story told by the law and letting the noise in the legal archive come through as noise instead of as potentially meaningful silence. Because Philip is not interested in a single voice or testimony (as Cowper and More are), I ask my students to consider what the fragmentation of language accomplishes that a ballad narrative cannot. Ultimately, I am interested in what kinds of justice, poetic or otherwise, emerge in each of these poems and what obstacles lie in the way of that justice.

Aside from assigning the first section of Philip’s collection, called “Os,” I also ask my students to read her essay “Notanda,” as well as Lord Mansfield’s brief decision in Gregson v. Gilbert, both of which are included at the end of Philip’s collection. The form that noise takes in Zong! is the violent disordering of legal language: “I murder the text, literally cut it into pieces, castrating verbs, suffocating adjectives, murdering nouns, throwing articles, prepositions, conjunctions overboard, jettisoning adverbs: . . . [I] create semantic mayhem,” she writes (193). The poems reconstructed from this mutilated language are spare and wild word arrangements on the page, liberated entirely from the restrictions of grammar and form. They can be read horizontally, vertically, and diagonally, either from top to bottom or the reverse. The thoughts and ideas that the word arrangements generate are not only specters of the transatlantic slave trade, they are also the dark matter of the law. If the law employs language to create order and meaning in the realm of human action, poetry can, Philip suggests, “engage language that is neither rational, logical, predictable, or ordered” (197). By subverting the legal language of Gregson v. Gilbert in an act of poetic violence, Philip conjures the shadows surrounding the Zong massacre to access the human sounds obscured by the trial: “Zong! bears witness to the ‘resurfacing of the drowned and the oppressed’ and transforms the desiccated legal report into a cacophony of voices—wails, cries, moans, and shouts that had earlier been banned from the text” (203). Unlike the singular voices constructed in the abolition ballads by Cowper and More, Philip’s voices are plural, fragmented, and just barely articulate. They do not tell a story as those ballads do; instead, they echo the senselessness of the Zong massacre in language that never really settles into a coherent account. Philip’s poems are thus fragments of voices that bubble up to the surface from the sea of history.

Because Philip’s poems begin from a place of abstraction, they pose many interpretive challenges for scholars and students alike. As spare word arrangements floating on the white page, Philip’s text encourages a kind of reading that breaks free from tradition. Instead of following a narrative thread, or even one channel of abstract thought along a single verse, the language of the poem surfaces at random as ideas, images, and concepts catch the reader’s attention. There is no order or story to discern in the poems—only fragments of voice and thought rescued from the restrictive legal documents of Gregson v. Gilbert. While the poems are challenging in their abstraction, they also present teachers with a rich opportunity for conversation in the classroom. Breaking the class into small groups, each of which spends time with one poem, can be especially productive. The groups might spend ten or fifteen minutes lingering with one poem and taking notes. Students make a collective list of the words, phrases, statements, or ideas that come through the language on the page. Each group then considers and discusses what the poem wants the reader to receive. After the exercise, we come back together as a class and project each poem on the screen, one at a time, for everyone to see. Individual groups review their notes with the class and report on what the poem spoke to them.

Before each group reports back to the whole class, I like to revisit Philip’s journal entry from July 12, 2002, which she includes in “Notanda.” Reading this entry informs our understanding of the element of haunting involved in Philip’s process of composition, which complicates my students’ sense of poetic agency:

This journal entry describes a conjuring. Philip’s process recalls a form of lyric possession described by Susan Stewart, but one that is markedly different as well. While the possession Stewart describes involves submitting one’s will to convention and to the irrationality of tune and meter, Philip is not plugging into the poetic tradition of the balladeer. She has a much more difficult task—to listen to the noise beyond the medium of the law for the voices silenced by the law, as if she were listening to voices under water. Philip burns incense, prepares herself for a visitation, and allows the words to “suggest how to work with them.” In listening for this kind of noise, Philip becomes a scribe for a story that can’t be told. Moreover, by submitting herself to ritual practice—burning incense—while listening to the British legal texts for the words to “leap out” at her, Philip’s process recalls the conjuring involved in obeah incantation. What makes this ritual unique, however, is its application of spiritual conjuring to the interpretation of British law. In this context, as an Afro-Canadian poet, Philip mediates the hauntological much like Cowper or More. It might be productive during this exercise to introduce Shepherd’s “The Negro Incantation,” which adopts the ode form to frame a Black obi voice, to underscore the radical significance of Philip’s approach. While Shepherd’s poem does capture the voice of Black colonial resistance, that voice is clearly bound by a white Western formal poetics. In Philip’s poems, however, Black voices are conjured and allowed to float freely on the page to make their own kind of noise, resisting the demands of a unified and coherent Western lyric subjectivity. This approach does justice to the historical denial of testimony by enslaved Black peoples in the discourse of the law while offering them a different kind of testimony, one that falls short of political voice but transcends legal silence.

What students may realize during their own reading experience is that it resembles Philip’s process of composition. That is, just as the words suggested their own arrangement to the poet, they also offer up bits of meaning in dynamic configurations in the process of reading. Moreover, students may observe that the poems do not only echo slave voices crying out but also offer up concepts from the legal texts that are up for critique or condemnation. Such configurations, when framed by the blinding whiteness of the page, arouse a horror that would be difficult to recognize if embedded in the original context. The work of making noise available to readers, Philip seems to suggest, sometimes involves dialing down the message of most of the original document(s) to make more audible those parts that we should linger on.

After each group presents their reflections to the class, I ask my students to critique Philip’s project and her creative/destructive dialogue between poetry and the law. I ask them what poetic justice means in a project like Zong! Does it matter that there is no single voice, or testimony, or point of view? Does abstraction get in the way of the story that “can’t be told”? I also ask them to compare the kinds of justice achieved by Cowper and More in their antislavery ballads. Those poems are unified voices and narratives and communicate a message that is intelligible and digestible for readers. Moreover, they allow the reader to engage in (or at least perform) acts of sympathy with the speakers in the poems. At the same time, they feature other voices (the sailors in Glover’s song) by way of music—is sympathy possible there? Or is music so subliminal that it bypasses sympathy? The most important question to ask about Zong! is whether sympathy is possible in such fragmented language. If sympathy can’t be generated, what is achieved by Philip? Whatever it is, is it more powerful than sympathy? If so, why?

One of the memorable classroom conversations that has emerged from this series of questions is one about the similarities between sympathy and haunting. If, as Adam Smith famously theorized, sympathy is a projective mechanism whereby we imagine ourselves in the place of the other, it is by its very nature a kind of possession. In Cowper’s and More’s poems, the performance of sympathy in connecting to the enslaved African experience may seem like haunting, but it may also be read as another form of colonization in which English sensibilities inhabit the bodies of others. At the same time, their use of Glover’s tune reminds us how unavoidably intertwined our histories are in a colonial narrative. In Philip’s project, however, haunting could never function as sympathy, for sympathy requires a coherent narrative or representation with which to identify. How do we connect to a story that can’t be told? The Zong! poems facilitate a haunting in the reading experience that does not require the exchange of subjectivity we find in sympathy. We could never, after all, embody the experience of the Zong massacre. Instead of hearing voices or testimonies from the sea of history, we can only listen to noise. Being attentive to that noise offers us, according to Philip, a more expansive ethical relationship to our traumatic past.

IV. Visual Noise

As a final exercise, one may introduce a group reflection devoted to visual noise by examining the political cartoon presented in Glover’s broadside alongside J. M. W. Turner’s famous painting The Slave Ship (1840), which Ian Baucom considers at length in his landmark study, Specters of the Atlantic (2005). Both images capture melancholy scenes in Britain’s maritime history, and both are commentaries on empire. Moreover, they are both haunting seascapes that conjure the dead from below the water’s surface. Perhaps the most significant difference, however, is the representation of the dead. While Glover’s broadside gives clear individuality and outline to the spirits of the sailors who perished during Hosier’s blockade of Porto Bello, Turner’s drowned slaves dissolve in the sea. Pictorially, the slaves in Turner’s picture lack distinction, and the eye must strain to identify individual persons in the obscure detailing in the painting. Turner could have chosen to capture a scene of the Zong’s slaves being thrown overboard, as his original title suggests, but he chose instead to eliminate identifiable human bodies from his work altogether. Human life is hauntingly signaled by red and orange color in the water.

Figure 2. J.M.W. Turner. Slavers throwing overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon coming on (“The Slave Ship”). 1840. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

What does it mean, one could ask the class, that the sailors of Hosier’s expedition receive individuality and voice as they address the victorious Admiral Vernon, who triumphantly captures Porto Bello with ships that proudly display the flag of Britannia? And what does it mean that in Turner’s painting the slaves thrown overboard become one with the sea in a horrifying, swelling tide of color and light? What is the power of Turner’s decision to abstract the human bodies in the water beyond recognition? After a conversation about this pictorial distinction, one could observe that these two images strikingly reflect the differences in representation we find between the abolition ballads by Cowper and More and Philip’s fragmented voices in Zong! In the latter, there is no lyric voice or identity to be distinguished in the text, only traces of subjectivity floating on the page. Visually, Turner found abstraction to be appropriate for an event so lacking in humanity. Why is that? While a clear picture of the atrocity is unavailable to us in Turner’s painting, the vibrant fragments in the water certainly come through as an alarming form of noise.