The debate’s over. I’m not going to debate with you any further. We have an area set aside for you. We’re providing you an area to go to that’s a public area, that’s visible, that you can do whatever you want to do. We’re not denying you a public spot. We’re denying you that one.

—Captain Scott Richards, Peabody Police Department, July 14, 2020

When my fellow Black Lives Matter activists and I arrived at the corner of Lowell Street and Russell Street in West Peabody, Massachusetts in order to stage a counterprotest in July 2020, we were immediately approached by members of the town’s police department and told that we had to relocate down the street to a marked-off location. Allegedly, the corner of the public sidewalk where we intended to rally had been reserved by a group under the organization of Dianna Ploss, a former radio host who had lost her job at a New Hampshire station after filming herself “berat[ing] landscape workers for speaking Spanish” (Taylor and Waller). When we informed one of the police officers that we were not moving to the designated zone down the street and that our counterprotest would continue as planned, the situation intensified. Our small group was quickly surrounded by seven officers, and after a conversation about our right to occupy this public space, we were told, “The debate’s over.” Yet the end of the debate about which space we should occupy would also have meant an end to the counterprotest itself, since that too was a form of debate.

Fortunately, I know that a permit is not needed to protest in the city of Peabody, and that public sidewalks cannot be reserved without proper documentation. At that point, a friend of mine signaled to one of our legal observers for assistance and began recording on her phone. In an attempt to de-escalate the situation, I told the police captain that we would not antagonize the rally, while also asserting that we had an equal, legal right to the public sidewalk. Perhaps due to the presence of the camera and the National Lawyers Guild observers, the police backed away from us, and we proceeded to successfully carry out our counterdemonstration. We received several signs that debate was not welcome that day; the police captain’s sentiment was mirrored in reactions we received from some of the city’s residents, who shouted profanities at us as they drove by. Yet the interaction with the city’s police department was instructive because it revealed that the act of protest could legally continue, even when we had been told that it could not. More importantly, it also revealed the need for persistence and for more sustained efforts in organizing for Black lives in my hometown.

Figure 1. Black Lives Matter protest in July 2020 in Peabody, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy of Casey K. Perez.

Figure 2. Black Lives Matter counterprotesters in West Peabody, Massachusetts. Photo by Jaime Campos of The Salem News, July 14, 2020, https://photos.salemnews.com/The-Salem-News-Newspaper-/July-2020/i-Hmx6zLd.

Figure 3. Peabody, Massachusetts police officer James Festa talking with protesters at Dianna Ploss’s rally. Photo by Jaime Campos of The Salem News, July 14, 2020, https://photos.salemnews.com/The-Salem-News-Newspaper-/July-2020/i-v5GF5zR

Reflecting on this moment in which the police tried to quell our protest with the phrase “the debate’s over” has led me to examine the powerful effect that antislavery pedagogy has had on my understanding of my own historico-political agency. Throughout this essay I will detail my trajectory in engaging with antislavery literature and pedagogy, first as an undergraduate student, then as a pre-service teacher, and finally as a scholar in the field of education and a social justice activist. I will also explain how my ever-shifting relationship with antislavery literature and pedagogy—a source of continual intellectual and affective debate—has informed my identity, experiences, and civic activity in each of these social roles. Overall, I aim to situate my experiences with antislavery curriculum, both as a student and as a teacher, within Paulo Freire’s concept of praxis, or as he defines it, “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (Pedagogy, 51).

Reading Antislavery Discourse at the Undergraduate Level

My initial contact with antislavery pedagogy began in Professor Joselyn Almeida’s “Introduction to British Literature” course when I was a first-year student at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Over the course of the semester, we read the work of many prominent abolitionists and other eighteenth- and nineteenth-century authors. For me, the three most powerful readings from this course for realizing my own potential for civic action through writing were Ottobah Cugoano’s Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery (1787); Mary Prince’s The History of Mary Prince, A West Indian Slave, Related by Herself (1831); and Friedrich Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845). In his fiery exhortation, Cugoano forcefully chastises the practice of slavery while simultaneously merging its history into that of the developing capitalist economic system. For example, one of the central aims of Thoughts and Sentiments is to locate the individuals and corporations who “steal, kidnap, buy, sell, and enslave” other humans, or as Cugoano dubs them the “merchandisers of the human species,” into the larger economic framework of capitalism, which permits and rewards these cruel and exploitative practices (51). In critiquing these “infamous ways of getting rich,” Cugoano splices together the despicable history of slavery and that of capitalism (70), anticipating the work of scholars such as Eric Williams, Ian Baucom, and Walter Mignolo.

Prince makes a similar point while describing her own experiences working as an enslaved person in the salt ponds of the Turks Islands. Prince notes how slave owners “received a certain sum for every slave that worked upon [their] premises” and how their profits derived from this unpaid labor (10). The force of Prince’s autobiography is how she goes on to elaborate the disturbing material conditions and details through which slave owners extracted labor from their captives. Furthermore, just as Cugoano decried the buying, selling, and merchandising of “the human species” for profit, Prince illustrates these horrors through her own personal testimony of being offered “for sale like sheep or cattle” (4). Even as her “heart throbbed with grief and terror so violently” at the reality of being ripped away from her mother and sisters, Prince clearly recognized that for those who bought and sold them, tearing apart this family was simply a matter of maximizing their profit margin. In other words, for the slave traders who “examined and handled [Prince] in the same manner that a butcher would a calf or a lamb he was about to purchase,” Prince’s enslavement, the separation of her family, and the sale of her body and labor power could be reduced to being “knocked down to the highest bidder” (4).

Cugoano’s powerful critique of capitalism and Prince’s vivid depiction of the conditions of slavery connect with the work of Engels in unexpected ways. Only a decade after Prince published her History, Engels delineates the brutal indifference of the ruling class and the relationship between the exploitation of the English proletariat and capitalism in his Condition of the Working Class. For Engels, capitalists can only generate profit in the form of surplus value through the “surplus labour” of the proletariat, which “costs the capitalist nothing, yet goes into his pocket” (314). Part of the power of Engels’s work relies on his depiction of workers with “[knees] bent inward and backwards,” “ankles deformed and thick,” “deformities of the pelvis,” and inhalation of “excessive dust, powder smoke, carbonic acid gas” (162, 253, 249). Although it is indisputable that the English working class were “far better off than slaves” (Prince 23), and the atrocious exploitation of the free laborers hardly approached the inhuman mistreatment of unfree laborers in all ways, reading Cugoano, Prince, and Engels together led me to interrogate the complex relationship between unfree labor, free labor, and capitalism unfolding in the nineteenth century.

This inquiry resulted in a term paper, which challenged me, as a student at the time, to reflect on ways I could deploy my writing against oppressive institutions and resulted in a more focused independent study with Professor Almeida on free and unfree labor. At the outset, the core question guiding the independent study focused on the dialectical relationship between the condition of enslaved laborers in the Global South (e.g., Cuba and Brazil), the condition of the working class in the Global North (e.g., United States and Britain), and capitalism as an international politico-economic system. In the syllabus we planned together, I aimed to deepen my knowledge of writers from the introductory course as well as to read other lesser-known figures, such as Thomas Spence and Robert Wedderburn. In addition, we sought to include more contemporary scholarship on the topic of slavery, such as texts by C. L. R. James, Eric Williams, David Brion Davis, Sidney Mintz, and David Eltis.

In reading these authors and scholars, it soon became more evident to me that the relationship between capitalism and slavery in the nineteenth century encompassed what Cugoano acutely established in his Thoughts and Sentiments. It confirmed Karl Marx’s famous assertion in the first volume of Capital (1867) that “the veiled slavery of the wage-earners in Europe needed, for its pedestal, slavery pure and simple in the new world” (833). It underscored Williams’s revolutionary and groundbreaking proposition that the profits of the transatlantic slave trade “fertilized the entire productive system of [Britain]” (105). By the end of the independent study, I argued in my term paper that capitalism as an economic force not only accommodated transatlantic slavery but also shared in a deep-rooted and fundamental relationship with slavery’s nineteenth-century development.

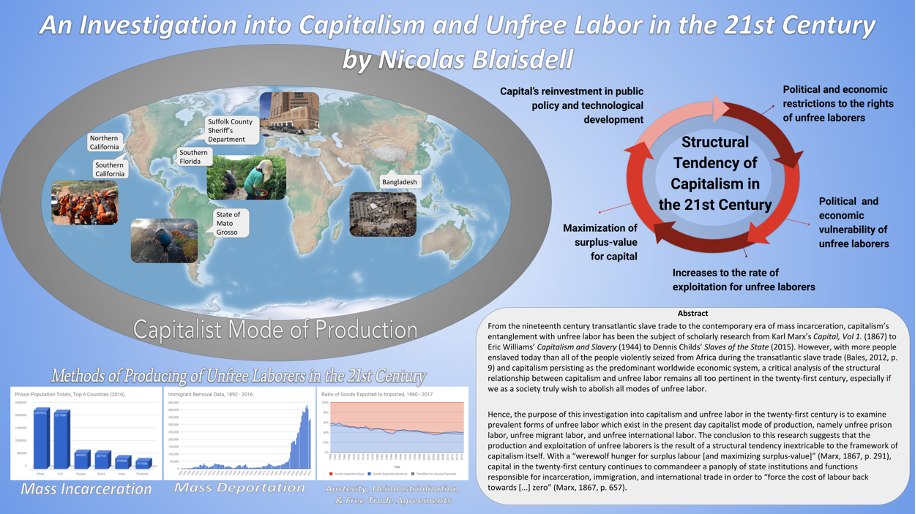

This idea became the basis for my undergraduate honors thesis the following academic year. Learning about the field of nineteenth-century antislavery literature led me to analyze the structural relationship between capitalism and unfree labor in the twenty-first century. To be more precise, I became interested in exploring Marx’s (triggering) assertion that not only did “the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting” of Black people signal “the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production” but also his recognition that unfree labor was inextricably and structurally intertwined with an economic system whose sole purpose is to “force the cost of labor back towards . . . zero” in order to maximize profits (823, 657). I wanted to apply my previous research to the project of exposing twenty-first-century forms of unfree labor structurally produced by the capitalist mode of production. As I examined specific examples of contemporary unfree labor and provided readers with direct action steps to advocate for unfree laborers today, I began to become more deeply aware of my own historical agency.

Drawing on the research of modern scholars across numerous disciplines, the three major forms of unfree labor in the twenty-first century that I explored in my thesis were unfree prison labor, unfree migrant labor, and unfree international labor. By reading Angela Davis’s Are Prisons Obsolete? (2003) alongside Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow (2010) and Dennis Childs’s Slaves of the State (2015), I was able to trace the racialized history of prisoners’ economic unfreedom from being legally designated as “slaves of the state” via the 1871 Virginia Supreme Court decision in Ruffin v. Commonwealth (as cited by Alexander, 31) to the hundreds of millions of dollars in profits generated by grossly underpaid, predominantly Black and Latinx prison laborers directly or indirectly in the production line of the federal government and a vast array of private companies including “Dell computers, the ParkeDavis and Upjohn pharmaceutical companies, Toys’R’Us, Chevron, IBM, Motorola, Compaq, Texas Instruments, Honeywell, Microsoft, Victoria’s Secret, Boeing, Nintendo, and Starbucks,” as well as TransWorld Airlines and Honda (Mosher et al. 95). On the topic of unfree migrant laborers, my thesis synthesized the research of immigration and slavery scholars Nicholas De Genova, Kevin Bales, Ron Soodalter, and Tanya Maria Golash-Boza to elucidate how U.S. immigration policy routinely converts already vulnerable migrant laborers into an illegal and, therefore, a highly docile and exploitable unfree workforce. For instance, one of the main areas of investigation of this portion of my thesis was the method through which major corporations like Exxon, John Deere, and Monsanto, along with large agribusinesses and the supermarkets and fast-food chains that buy from them, could profit from the inexcusable conditions of enslaved, coerced, and unpaid labor of migrant workers (Bales and Soodalter 47–8). The last section focused on how the structural tendency of capitalism, as embodied by massive multinational companies, routinely colludes with governments and financial institutions to produce and exploit unfree international workers for the production, accumulation, and maximization of surplus value. For example, my explanation of unfree international labor directly linked Apple’s 2019 market value of $1.8 trillion (“Apple”) to the countless Chinese workers who are reportedly being forced to “hand[le] noxious chemicals sometimes without proper gloves or masks” while standing “10 hours a day in hot workshops slicing and blasting iPhone casings” (Gao and Webb).

Ultimately, the overarching claim of my undergraduate honors thesis was that the production and exploitation of maximally vulnerable and exploitable unfree laborers in the twenty-first century is the result of a structural tendency inextricable from the framework of capitalism itself. This structural tendency, or “directing motive, the end and aim of capitalist production,” immediately derives from capital’s insatiable need to produce, accumulate, and most of all, extract “the greatest possible amount of surplusvalue,” which is achieved by continuously attempting to “force the cost of labor back towards . . . zero” (Marx 363, 657). In my conclusion I suggested that capital in the twenty-first century continues to commandeer a panoply of state institutions and functions responsible for incarceration, immigration, and international trade in order to realize its structural impetus for producing, accumulating, and maximizing its share of surplus value.

Figure 4. The author’s presentation at the Undergraduate Research Conference, University of Massachusetts Amherst, April 2018.

Overall, with my focus now shifted toward uncovering and critiquing manifestations of slavery today, I soon began to recognize the relationship between my research in antislavery literature and the contemporary need to dismantle the political and economic institutions continuing to produce unfree laborers. My research and writing became a moment for me to link my investigations from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to our present, while simultaneously exploring ways to discern my place in impacting the historical and material conditions of the twenty-first century. At this point, I began to experience the way that, as Michel Foucault describes, “discourse transmits and produces power; it reinforces it, but also undermines and exposes it, renders it fragile and makes it possible to thwart it” (101). However, in reflecting upon Freire’s notion that “the process of problematization implies a critical return to action,” my ambitions in regard to antislavery pedagogy again shifted: rather than merely focusing on finishing my thesis, I also developed a growing desire to engage in more direct civic action (Education, 135).

Translating Antislavery Discourse into Action as an Undergraduate

One of the first methods I explored for participating in civic engagement was petitioning the state. The murder of Heather Heyer at the white supremacist “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017 moved me to action. That year, I started a petition to remove the state of Massachusetts’s only Confederate memorial, on Georges Island in Boston Harbor. The importance of understanding the history of antislavery movements to the present moment was made explicit by the way that white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and many Donald Trump supporters had utilized pro-slavery symbols, like Confederate flags and Southern Nationalist flags, when they all marched together at the “Unite the Right” rally. Since my education had focused on narratives of antislavery from the era of the Confederacy, I understood the historical relevance of nationwide protests aimed at removing public statues commemorating Confederate soldiers in response to the rise of far-right extremism and violence.

I was also led by my studies to engage with my local and state government in more direct modes of action. After my examination of prison labor in my thesis, I began drafting public records requests under the Freedom of Information Act and the Massachusetts Public Records Law. Even though I always had the legal right and capability to issue public records requests, it was only after being inspired by the canny ways that nineteenth-century abolitionists manipulated the existing legal system to advocate for their antislavery agenda that I began to realize how I might put this freedom to best use. I recalled how the various abolitionist societies that emerged across England in this period were able to organize unprecedented petitions, protests, legal proceedings, and other forms of civic action. For instance, in the four weeks following a proposal at the Congress of Vienna to “renew the rights of French slave-merchants,” English abolitionists were able to get “a higher proportion of the population” to sign antislavery petitions than any other petition of the time, including the massively popular Chartist petition of 1848 (Fryer 213). I was also profoundly inspired by the work of Granville Sharp, who won the famous Somerset v. Stewart case (1772) that outlawed the forcible removal of slaves from England. Sharp also fought vigorously alongside Olaudah Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano in the Zong case (1781) to hold accountable the slave traders who massacred over 130 enslaved people in order to fraudulently collect insurance money.

Filing public records requests in Massachusetts also allowed me to find more specific data regarding the potential collusion between the state, prisons, and capital in relation to the production and exploitation of unfree prison laborers. The outcome of these records requests revealed that the city of Boston had contracts for prison labor, despite the Massachusetts law establishing that “no contract shall be made for the labor of prisoners” (M.G.L. Chapter 127, Section 51). I also uncovered the fact that prison laborers from the Suffolk County Sheriff’s Department were excluded from the living-wage agreement that vendors contracting with the city of Boston must sign, meaning that there was legally no minimum wage for prison workers contracted to the city. In some instances, contracts I obtained through public records requests showed how prisoners working through a Massachusetts Department of Correction program called “MassCor” earned as little as 40 cents per hour while producing a wide range of products, including “certificates, beds, binders, padfolios, clothing, decals, embroidered garments, flags, janitorial supplies, mattresses, pillows, chairs, desks, and tables, office signs, name tags, street signs, park benches, picnic tables, fire pits, bike racks, trash receptacles, engraved wood, brick, granite and stone, sheets, and towels” for purchase by both public and private entities (MA DOC 3).

The principles I garnered from reading and analyzing abolitionist and Marxist literature also led me toward other avenues for realizing my potential as an agent of social change, specifically in the field of education. During the summer of 2016, I founded the Peabody Volunteer Tutoring Organization (PVTO), which has since partnered with the Peabody public school system to provide free summer tutoring every year to hundreds of students ranging from grades one through twelve in mathematics, science, English, history, and test preparation. My desire to grant students and families of disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds access to the additional levels of summer support that have been routinely reserved for their more privileged counterparts, and modestly to contribute to an atmosphere of community empowerment and solidarity in the city of Peabody, stemmed from my yearning to disrupt what the Marxist scholar David Harvey identifies as “accumulation by dispossession,” specifically within the realm of public education (New Imperialism, 144). With a wide range of scholarship documenting the horrific inequities in American schooling from Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis’s Schooling in Capitalist America (1976) to Jonathan Kozol’s Savage Inequalities (1991) to Pedro Noguera’s City Schools and the American Dream (2003), the need for immediate individual and community action to subvert these systems that regularly dispossess students of marginalized racial and economic backgrounds of access to quality educational experiences became my top priority that summer. For me, it was clear that this wide-scale educational inequity was a process deeply rooted historically in the rise and expansion of capitalism and the Atlantic slave trade.

Realizing Historical Agency and Racialized Dispossession in the Classroom

Upon graduating from UMass Amherst with my bachelor’s degree in English, I began more directly to witness the “accumulation by dispossession” process firsthand while entering a high-poverty urban school district in western Massachusetts as part of the residency portion of my graduate program to earn a master’s degree in the field of education. During my time as a pre-service student-teacher in this school, I was exposed to the harsh material conditions of education in the United States, a system that routinely works to effect the dispossession I described above, which in turn limits future economic and social mobility. Before elaborating on the relationship between my own undergraduate work and my experiences in this particular school district, I will first detail the contexts of student learning in this setting.

The school itself, formerly a Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance corporate building, was located across the street from a brand new MassMutual location. In a stark contrast to the $39.2 billion that MassMutual earned in revenue during the previous year (“Massachusetts Mutual”) and the statewide median household income of $77,378 (United States Census), some students attending the school came from neighborhoods in which the median annual family income was estimated to be a meager $15,311 (FFIEC). Moreover, with “segregation along racial, ethnic or other lines” being “notoriously pervasive features of all capitalist social formation” (Harvey, Seventeen Contradictions 68) and “a higher percentage of Black children” attending “segregated schools now than in 1968” (Knopp 27), the demographics of the school mirrored this reality and were not at all proportional to the demographics of the state of Massachusetts. According to data from the state’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, 17.6 percent of students at the school identified as African American, 70.8 percent as Hispanic, and 8.5 percent as white (MA DESE). For purposes of comparison, 71.1 percent of all residents in the state of Massachusetts identify as white (United States Census). In other words, compared to the rest of the state, the school was clearly segregated along lines of race and class, despite the Brown v. Board of Education (1953) Supreme Court ruling declaring that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal” nearly seventy years before (Warren 495).

The staff of this school wielded a disproportionate amount of power over students. The teachers and administrators were mostly white and of upper-middle-class backgrounds, making it clear to me that this school was the embodiment of what linguist Mary Louise Pratt identifies as a “contact zone,” or a social space “where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out in many parts of the world today” (34). As a student with a background in antislavery and resistance pedagogy, entering this contradictory contact zone as a pre-service teacher meant that I understood I had the potential to either “reproduce socioeconomic and racial inequalities” or “[build] critical consciousness . . . and revolutionary resistance” (Au 90). This awareness led me to design a pedagogical unit that aimed to dismantle one particular instance of a racialized and classist school policy harming my new students: the school dress code.

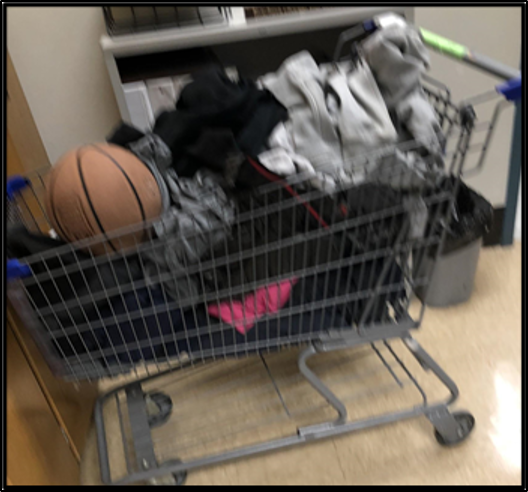

The district’s dress code policy, which banned any article of clothing with a hood, was firmly entrenched in a history of anti-Black and anti-Brown racism in the United States. Under the guise of promoting public safety, Black and Brown children were being targeted. The underlying logic maintaining the dress code policy was the misguided and racist belief that these children are more dangerous than other children and therefore should not be allowed to wear anything that could potentially conceal their identities in schools. Ideologically, this was the same belief system that allowed the murderer of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black student, to be found innocent of second-degree murder and even of the lesser charge of manslaughter (Alvaraz and Buckley). In practice, the enforcement of the district’s dress code meant that the school’s predominantly white teachers and administrators would waste valuable class time stripping Black and Brown students of their winter clothing, whether a hoody or a hooded jacket or coat. I can vividly recall sitting in the back of a math class when the school’s principal halted the lesson by entering the room with a grocery cart and making students take off their jackets one by one and put them in the cart. After the principal left, I remember watching one student shivering at his desk in a T-shirt for the remainder of class. On another cold fall morning, I heard an assistant principal boast in the hallway how he “snagged another one,” referring to a student’s hoody. On this particular day, it was so cold that it hurt my hands to type: how must the student have been feeling, without his sweater? More shockingly, the enforcement of the dress code continued all through the harsh New England winter, even as outdoor temperatures fell well below zero and even as some of the school’s defective HVAC systems blasted freezing outdoor air directly into classrooms.

Figure 5. The school's hoody cart by Nick Blaisdell.

The racialized, institutional violence and dispossession that the school’s dress code inflicted on my new students prompted me to consider ways I could leverage my curriculum to ignite student-based civic action. More specifically, after reflecting on the potential power that petitioning against and publicly exposing injustice had, I decided to base my “Persuasive Writing” unit on changing the dress code. Throughout the course of the unit, students composed argumentative letters addressed to the district’s school committee. I also wanted students to use these letters to participate in a speak-out event that the school committee had planned in the spring of that school year to publicly reveal the true and disturbing reality of the dress code policy. Working with students to write these letters was by far one of the most transformative experiences in my career as a teacher. In an approach that was based on synthesizing research and their specific day-to-day material conditions, my students wrote cogent and powerful arguments for why the dress code should be changed.

It came as no great surprise that these arguments were quickly censored by the school’s administrators. When they learned that I was working with students to present our case to the school committee, a number of administrators visited my classroom with the aim of disrupting our plan to disseminate the letters. My students were falsely told that their constitutional right to freedom of speech and expression could not be exercised at a school-run event. Although this was counter to the 1969 Tinker v. Des Moines Supreme Court decision that established that neither “students [nor] teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate” (Fortas 506), my students were legitimately afraid to say anything that might upset the school’s administration, especially because it was common practice to detain students through in-school suspension for even very minor violations of school policy. For myself, I remember being told in no uncertain terms that being vocal about this issue could potentially impact my future career prospects as an educator because “principals and superintendents talk.”

In the end, we were unable to send the letters. But despite this repression of student and teacher resistance, the instructional unit still had a tremendous impact on my students’ historical and political conceptions of themselves. In a post-unit reflection, one of my students wrote: “Having gone through this unit, I would want you to teach your future students this lesson. You taught us that we must stand up against the people of power and that it’s wrong for them to be holding us back. This lesson taught me that we have rights that are being taken away and changed just because the color of our skin and because [of] our ages. You told us to fight against the system because the system is corrupt.”

Overall, my students’ powerful remarks indicated that the unit succeeded in promoting their awareness of their historical agency and capacity for civic action. By the end of the unit, students recognized that there will always be pathways for resistance and subversion and that they must always continue fighting for their rights regardless of the systemic barriers that powerful institutions will leverage against them. Students also learned that the power of social change begins and is sustained through collective civic action. In short, my unit was able to teach students the core values I internalized from studying antislavery pedagogy, all through the framework of a curriculum of praxis.

The Black Lives Matter Movement and Teaching for Civic Action

Notwithstanding experiences that could have derailed me from the path toward becoming an educator, the lesson of resilience allows me to conclude this essay with a reflection on what I have learned in my latest role as a teacher in the city of Revere, Massachusetts, alongside my continuing role as a social justice activist in Peabody. After the murder of George Floyd, a few colleagues and I formed a community organization called “Peabody for Social Justice.” Our main focus has been raising awareness of the ways through which the United States systematically attacks the lives of Black Americans and people of color, whether through the militant policing of Black and Latinx neighborhoods, the chronic underfunding of public education systems that primarily serve students of color, the perpetuation of racialized and class-based inequities in the healthcare industry, the unfair criminalization and imprisonment of people of color, the grotesque exploitation of workers in predominantly Black and Brown communities, or by any other means. In the words of our mission statement, we seek to “promote the values of liberty, equality, and justice for all in our city, regardless of any individual’s race, ethnicity, religion, cultural background, linguistic background, gender, sexuality, ability, economic class, immigration status, or nationality.” To achieve this goal, we began by leading a series of antiracism and anti–police brutality protests and rallies across our predominantly white, middle-class suburban city. Next, we were able to arrange a meeting with the city’s mayor to discuss more concrete and long-term political changes to make Peabody more equitable and socially just. Some of the activities we proposed included conducting thorough reviews of city policies, ordinances, and services for race- or class-based biases; collecting and publishing data regarding the day-to-day operations of city institutions; and organizing rallies and other events to promote the need for social justice.

In the spring of 2020, activists in Boston beheaded the statue of Christopher Columbus that faced the waterfront in the city’s North End. Such events demonstrate that the ongoing wave of civic action across the United States can be clearly traced back to the continuous work of fighting against the legacy of slavery and contemporary manifestations of white supremacy. When I returned to school after my summer of activism, I continued to develop more robust civically-motivated lessons and antiracist curricula to spark my students’ understanding of their own historical agency. For example, one instructional unit I devised asked students to investigate and analyze current Massachusetts legislation that involves the rights of marginalized socioeconomic groups and learn how they can fight for social change at the state level by lobbying their elected officials. I also continue to support students by incorporating the skills I learned from my early activism to help them lobby for political changes that they want to see in the city, state, and beyond. In alignment with the principles of antislavery pedagogy and Freire’s theory of praxis, I expect my students to utilize their ability to read, analyze, and produce sustained discourse to influence social change, as well as participate in more physical events of civic action.

Now more than ever, we must embrace this emancipatory praxis promulgated by Freire. As critical educators, we are constantly reminded that our roles and responsibilities to our students extend far beyond the dominant “banking” concept of education, through which “the students are the depositories [of knowledge] and the teacher is the depositor” (Freire, Pedagogy 72). Instead, we must actively encourage students critically to examine the structures of power and exploitation in their surrounding material conditions. By consistently integrating theory and praxis in the classroom and offering students alternative visions of the future, we can tap into their emerging conceptions of justice, equality, and fairness. In my classroom, this looks like students conducting individually led, sustained-action research projects based on social justice issues related to the course’s theoretical frameworks.

One project that encapsulates these ideas is the final project for my “World Revolutions” unit. After students have learned about the conditions, beliefs, and triggers of some of the world’s most significant revolutions, I ask them to research a country or place they believe is ripe for a revolution today. In this project, students are invited to integrate their understanding of the social, political, and economic causes of earlier revolutions with the current historical moment. Rather than acting as a “depositor” of information, my role in the classroom is to facilitate, challenge, and offer support as students explore the material conditions of the past and present and the various theoretical frameworks for interrogating it, such as Cugoano, Engels, Marx, Prince, Williams, and others. Through self-directed, sustained-inquiry projects like the ones I’ve described, we can ignite students’ passion for a better world, a world free of slavery, exploitation, and oppression. As the story of my experiences with antislavery pedagogy demonstrates, it was ultimately this kind of undertaking at various stages of my development that guided and critically informed my trajectory from student to researcher to educator to social activist and back.

Although the challenges and institutional powers before us today in the twenty-first century are unprecedented and complex, we cannot forget the historical importance of the spirit of resilience to the project of abolition and social justice. As Cugoano wrote: ‘This must appear evident, that for any man to carry on a traffic in the merchandize of slaves, and to keep them in slavery; or for any nation to oppress, extirpate and destroy others; that these are crimes of the greatest magnitude, and a most daring violation of the laws and commandments of the Most High, and which, at last, will be evidenced in the destruction and overthrow of all the transgressors. And nothing else can be expected for such violations of taking away the natural rights and liberties of men. (61)’ The abolitionists of the nineteenth century were up against some of the most powerful, vicious, and despicable institutions of modern human history. Yet in their fight against the transatlantic slave trade—the cradle of capitalism and present-day neo-slavery—the abolitionists, radicals, and revolutionaries never ceased to envision a world in which transgressors were overthrown and the rights and liberties of all people were upheld. Antislavery pedagogy in the era of Black Lives Matter reminds us of the work that we must do to keep ourselves united and organized to promote freedom and equality for all. Claiming our own historical agency and the field for civic action means insisting that debate must persist, even when authorities tell us it cannot.