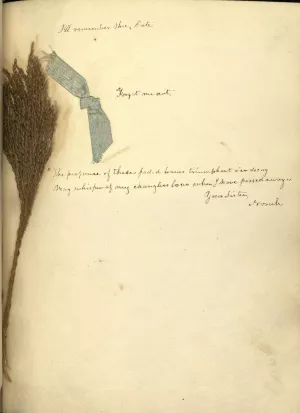

In Stéphanie de Genlis’s 1798 novel Les Petits émigrés: ou Correspondance des jeuns enfans (translated in 1799 as The Young Exiles and much reprinted over the next two decades), the young heroine, member of a royalist family that has fled revolutionary France for asylum in a country village near Zurich, sends a gift to a cousin who has remained behind. It is a sort of blank book, one that Juliette D’Armilly identifies as a Swiss or German “invention,” and which is to serve her dear Adriana, she writes, as “a book of remembrances” (un livre de souvenirs in the original French). The letter Juliette writes to accompany her present reads like a how-to manual drawn up for her cousin’s use. As she explains, “all the persons one loves are requested to write something in [the book]; one sets down in it one’s own thoughts, and draws landscapes, flowers, or heads; and after a certain time the book becomes filled with interesting things.” Later in the letter she supplements these instructions and describes the materials she has gathered to fill up a companion book of remembrances purchased for her sister: ribbons, locks of her hair, plants from their garden. With the latter, she emulates her older brother, who in the novel’s first letter writes of sending Adriana specimens of a plant, native to Switzerland, which he has culled and dried himself. Edward calls the flower by its German name Vergiss-mein-nicht, while, in a footnote, Genlis’s English translator identifies it as a forget-me-not.

Epistolary fictions such as Les Petits émigrés depend on their audience’s willingness to imagine, beyond the typeset pages they hold before their eyes, the scrawled, blotted, tear-stained manuscript letters that the novel’s characters are creating and on which they are commenting. In Les Petits émigrés Genlis goes further, however. Readers of her novel—which as a mass-produced printed object leads a distributed existence in the form of hundreds of uniformly manufactured copies, each interchangeable with another—are required to conjure up in imagination a volume that has been created and assembled by hand, which is one of a kind, and which, as a shrine to memory in bookish form, collects mementoes of people and places and preserves them in all their material singularity.

Through the first half of the nineteenth century, this book type, promoted by Genlis as a novelty, would become ever more familiar, popularized, as often as not, under the title of “album”—the term that was favored by, among others, the many publishers (in Britain and America, as well as in France) who began in the 1820s to manufacture blank books custom-made for the mnemonic and sentimental purposes that Juliette D’Armilly describes. The history of the album has a tremendous amount to teach us about the intersection of the book history of the nineteenth century both with visual culture and with the history of emotion. Through it we can retrace, as well, the Romantic-era transition influentially charted by the critic Judith Pascoe, in which “the souvenir as mode of memory becomes the souvenir as marketable object.”

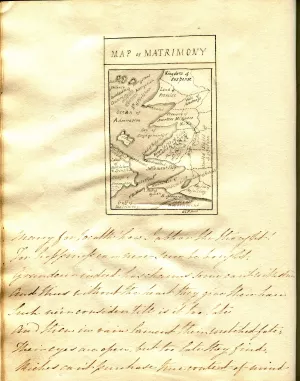

Back in 1755 Samuel Johnson in his Dictionary had defined “album” as a “book in which foreigners have long been accustomed to insert the autographs of celebrated people”: he was likely thinking of the early modern tradition of the album amicorum and of the fashion, launched at the German universities in the sixteenth century, for amassing in a blank book the signatures of the eminent acquaintances whom the gentleman student had encountered there. The nineteenth century witnessed, however, the rapid naturalization of this book type in the English-speaking world, and also its domestication, feminization, and commodification. How-to instruction of the sort provided in Les Petits émigrés quickly became unnecessary. By the 1820s, these homemade and home-defining books had become standard fixtures of genteel parlors throughout Britain and America. There they served to memorialize the personal relationships cultivated in those settings and to display the talents, aesthetic aspirations, and emotional commitments of the people involved. Within nineteenth-century album culture, the keeping of friends and the conserving, through copying or clipping, of memorable images or pieces of text were understood to be enterprises that went hand in hand.

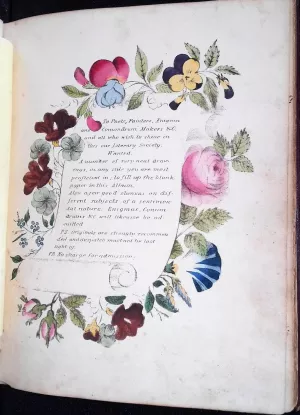

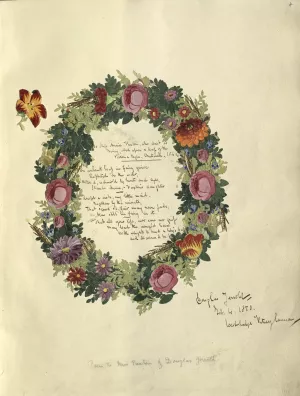

This gallery samples an assortment of pages culled from albums assembled by social networks located on both sides of the Atlantic during the late Romantic era. It aims to restore these books to their central role in the vernacular visual culture of the nineteenth century. Although nineteenth-century men also kept albums, the books sampled here for the most part belonged to young women (though, in some cases, both the genders and identities of their owners and creators have proven impossible to discover). Many of these albums seem to have been, in fact, exhibition spaces in which the owners’ female acquaintance showed off the talents that at this time defined the “accomplished woman”—flower painting in watercolors representing a particular favorite. This sort of book also showcased the manual dexterity that nineteenth-century women brought to fiddly activities such as calligraphy, cut paper work, or the making of hair wreaths. Thus, in the ninth chapter of Jane Austen’s Emma (1816), as readers learn of the album of “enigmas, charades, and conundrums” being compiled by the heroine and her protégée Harriet Smith, we also hear that Harriet’s chief contribution to their joint enterprise is the “very pretty hand” in which she will be writing out the content they have sourced for their book. As Austen acknowledges, young women were, in an indirect way, displaying their bodies on these pages.

Adolescence and young womanhood were in general the times of life in which women were most deeply engaged with their albums. One strategy that we adopt in this gallery to register that dimension of album culture is that we have often selected pages that foreground in their visual content the overlap between the album and other contemporary book types such as the herbarium collection and the floral dictionary. For young women, who, according to the fulsome idiom of the period, were often said to be blooming themselves, the floweriness that pervades the nineteenth-century album was deemed particularly appropriate. (“Young ladies are delicate plants,” purrs Emma’s Mr. Woodhouse.) Often atop a single album page one can encounter a handwritten poem about flowers, a painting representing flowers, and pressed specimens of flowers. To present a floral tribute to a young woman was a conventional piece of gallantry—flowers being, after all, traditional symbols of feminine beauty. But since a girl grows up, and since flowers are the harbingers of fruit, this choice of gift also tacitly broached matters of sexuality and reproduction; it alluded to the young woman’s erotic availability and procreative destiny.

With our selection of materials, we have in addition sought to suggest the longevity of the themes of dislocation, exile, and loss that Genlis foregrounded in Les Petits émigrés—themes that, sounded there, register how her wanderers’ letters originate in a context of revolution and war. Even as the album was familiarized and absorbed into the domestic life of the nineteenth century, it continued to serve as a resource that its owner could use to acknowledge and/or palliate her anxieties about a future separation from her friends or a future loss of a home. The mementoes that these examples of the “livre de souvenirs” gathered up were valuable not so much in themselves but for their capacity to carry the past into the present. The album’s contents, that is—either hallowed by their association with particular people and places, or (as with the locks of hair and pressed ferns and violets) cherished as the literal relics, the material traces, of particular people and places—were ascribed the power to reaffirm and even remake connections that might seem hopeless of repair. When the literary critic Samantha Matthews observes that albums were often presented to their owners as “threshold gifts”—objects used to mark the recipient’s passage from girlhood to adulthood—she gestures toward this value system and helps clarify the nature of the emotional service these objects were understood to provide. The album was designed to be travel-ready. It generally journeyed along with its owner when she left school and accompany her once again when as a bride she relocated from her parents’ house to her husband’s; it was often at these moments of leave-taking that she would circulate it among her acquaintance, requesting their contributions to its pages. In arranging for this gallery to include, alongside pages of painted or pressed forget-me-nots and rosebuds, a page that memorializes Napoleon Bonaparte’s exile after Waterloo and a page from an album referencing the Bible stories of the female exiles Hagar and Ruth, we aimed to register the dislocations and separations that even in times of peace remained central to nineteenth-century female lives.

Like an album, this gallery is the work of many hands. As interns with Harvard’s SHARP program (Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program), Norah Murphy (Harvard Class of 2020) and Faith Pak (Harvard Class of 2019) began working on it with Deidre Lynch, Ernest Bernbaum Professor of English Literature at Harvard, in the summer of 2018. We three were assisted greatly by Emilie Hardman and Christine Jacobson at the Houghton Library, by Ellen Shea at the Schlesinger Library, and by Elizabeth Denlinger, Curator of the Carl H. Pforzheimer Collection of Shelley and His Circle at the New York Public Library. Deidre Lynch is also grateful for the opportunity to inspect Romantic-era albums alongside the undergraduates of English 145a, “Jane Austen’s Fiction and Fans,” and grateful for the insights into books, social media, and fandom that these students always bring to the table.

Date Published

Exhibit Items

Exhibit Bibliography

Andrews, James. Lessons in Flower Painting. London: Charles Tilt, 1836.

Bermingham, Ann. Learning to Draw: Studies in the Cultural History of a Polite and Useful Art. Yale UP, 2000.

Eckert, Lindsey. “Reading Lyric’s Form: The Written Hand in Albums and Literary Annuals.” ELH, vol. 85, no. 4, 2018, pp. 973–97.

Genlis, Madame (Stéphanie Félicité) de. Les Petits émigres, ou Correspondance de quelques enfans; ouvrage fait pour l’éducation de la Jeunesse. 3rd ed., Maradan, 1803.

Gernes, Todd S. “Recasting the Culture of Ephemera.” Popular Literacy: Studies in Cultural Practices and Poetics, edited by John Trimbur, U of Pittsburgh P, 2001, pp. 107–27.

Harris, Katherine D. Forget Me Not: The Rise of the British Literary Annual, 1823–1835. Ohio UP, 2015.

Holway, Tatiana M. The Flower of Empire: An Amazonian Water Lily, The Quest to Make It Bloom, and the World it Created. Oxford UP, 2013.

Kelley, Theresa M. Clandestine Marriage: Botany and Romantic Culture. Johns Hopkins UP, 2012.

King, Amy M. Bloom: The Botanical Vernacular in the English Novel. Oxford UP, 2003.

Lynch, Deidre Shauna. “Paper Slips: Album, Archiving, Accident.” Studies in Romanticism, vol. 57, no. 1, 2018, pp. 87–119.

Matthews, Samantha. “Albums, Belongings, and Embodying the Feminine.” Bodies and Things in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture, edited by Katharina Boehm, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp. 107–29.

———. “Importunate Applications and Old Affections: Robert Southey’s Album Verses.” Romanticism, vol. 17, no. 1, 2011, pp. 77–93.

Pascoe, Judith. “Poetry as Souvenir: Mary Shelley in the Annuals.” Mary Shelley in Her Times, edited by Betty Bennett and Stuart Curran, Johns Hopkins UP, 2000, pp. 173–84.

Roberson, Jessica. “Shelley’s Grave, Botanical Souvenirs, and Handlings Literary Afterlives in the Nineteenth Century.” Victoriographies, vol. 6, no. 3, 2016, pp. 276–94.

Sheumaker, Helen. Love Entwined: The Curious History of Hairwork in America. U of Pennsylvania P, 2007.

Sloan, Kim. A Noble Art: Amateur Artists and Drawing Masters, c. 1600–1800. British Museum Press, 2000.

Tyas, Robert. The Sentiment of Flowers: or, Language of Flora. Lea and Blanchard, 1840.