Height

19 cm

Width

15 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

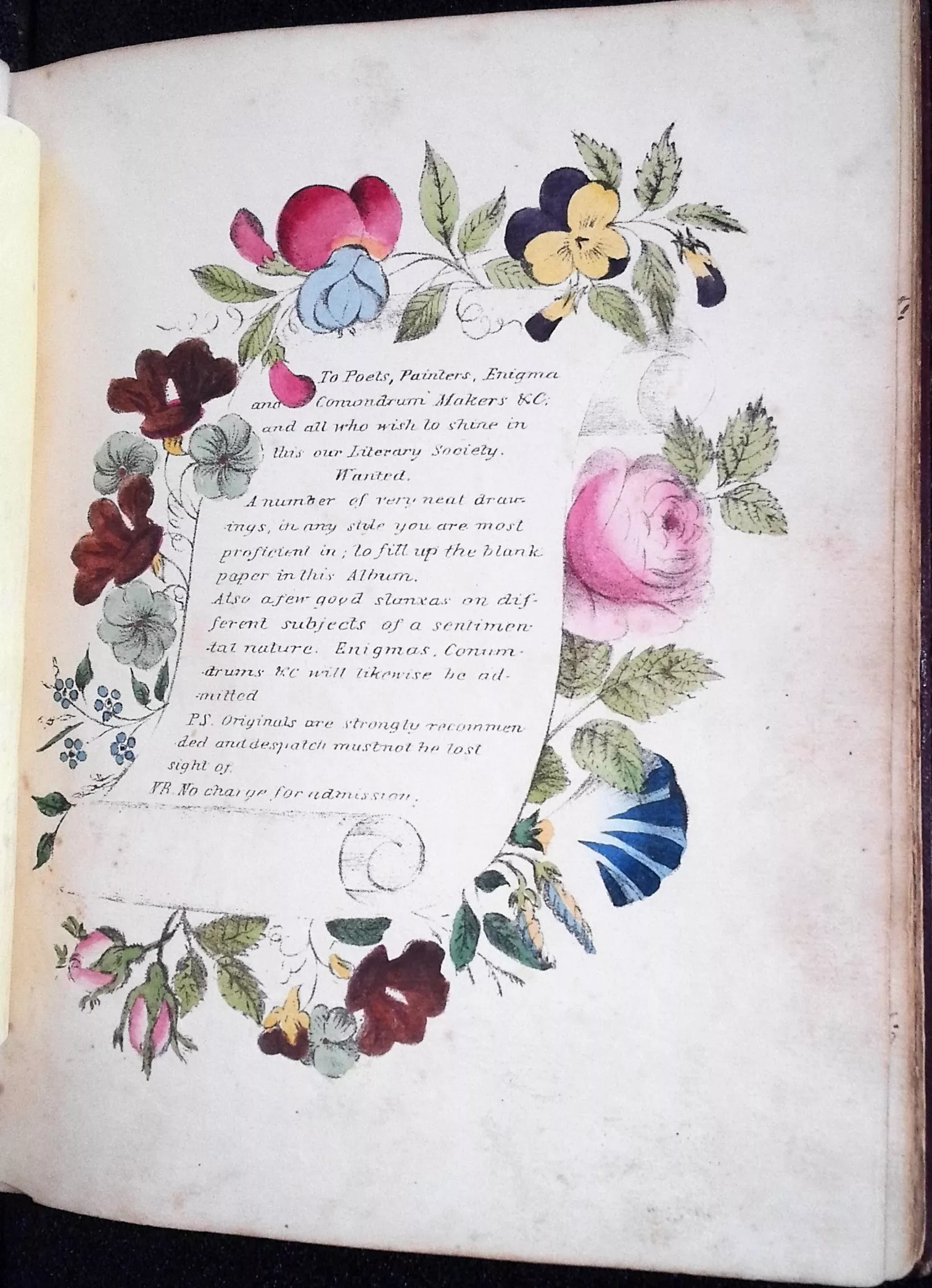

Here, on one of the four engraved and hand-colored pages interspersed among the blank pages of the Floral Album, the engraver has pictured a wreath of flowers formed from pink roses, blue morning glories, a spray of forget-me-nots, pansies, and other blossoms. These are flowers often mentioned in the floral dictionaries of the early nineteenth century: the pink rose, for instance, symbolizing youthful love. Extending from the middle of this floral wreath is a scroll, which is no longer entirely unrolled: the engraver has tried for a trompe-l’oeil effect, adding an illusion of texture to the page by making it seem as if the paper has begun to curl and the scroll has become detached. A tissue guard that is tinted bright yellow precedes this page, placed there to protect its colors and also add to the book’s colorfulness.

With some of the words seeming to peek out from beneath the blossoms, the message imprinted on the scroll reads as follows:

To Poets, Painters, Enigma

and Conundrum Makers, &c.

and all who wish to shine in

this our literary Society.

Wanted

A number of very neat draw-

ings, in any style you are most

proficient in, to fill up the blank

paper in this Album.

Also a few good stanzas on dif-

ferent subjects of a sentimen-

tal nature. Enigmas, Conun-

drums &c will likewise be ad-

mitted.

PS. Originals are strongly recommen-

ded and dispatch must not be lost

sight of.

NB No charge for admission

Appealing to its readers to step up as content-providers and assist in filling up this volume’s blank leaves, this mock-advertisement interjects a note of jokey self-consciousness into the Floral Album. In borrowing its idiom from the help-wanted columns of contemporary newspapers, the text on the scroll aligns the affectionate gift exchanges that defined album culture with the money-making ventures of the commercial sphere, as well as with the more exalted artistic enterprises that one might normally associate with the phrase “our literary Society”. The cultural conventions that would tend to separate those three sets of activities are thereby set at defiance, if only in jest.

This sort of humorous self-reflexivity about how albums were made and how they ranked in the artistic hierarchies of the culture was actually quite typical of Romantic-era albums. That archness leavened a bit their commitments to love and to gallantry about feminine beauty and feminine innocence—as the occasional “enigmas” and “conundrums” (riddles) contributors wrote out on their pages did as well. The three engraved plates that follow this one in the Floral Album do put the usual sentimental content back into the spotlight, however, at the same time that they also live up more whole-heartedly to the aesthetic commitments announced by the title Floral Album. Those three pages pair their pictures of hawthorn blossoms, woodbine, and moss roses with verses, not original to this album, that, respectively, mourn the ephemerality of beauty, praise rural simplicity, and recount a fable in which the origin of the moss rose is fancifully traced (an angel grants a rose its wish for an added grace and, so, “robed in nature’s simplest weed,” the moss rose springs into existence).

The identity of the engraver of the four pages produced in this style is uncertain. The title page of this copy of the Floral Album has an engraved vignette picturing a man, possibly meant to be Native American, kneeling on a rock beside a lakeshore and gazing across the waters. The image is signed E. Gallaudet, the name of a frequent contributor to illustrated books (literary annuals especially) in early nineteenth-century America. Given that the floral plates that follow this title page are in a very different style, this title page might well have been pressed into service in any number of the several albums that J. C. Riker manufactured between the 1820s and 1850s.

The copy of the Floral Album now housed in the Schlesinger Library at Harvard belonged to Olive Nickerson Paine, who was nineteen when she was given the book in 1839. She married Charles A. Hannum in 1847. The majority of the verses inscribed on her album’s pages can be dated to the years of her youth and courtship. Albums were given to girls to serve as memorials to the friendships that antedated their marriages, friendships that would be left behind as they embarked on a new phase of life. Much of the poetry donated to the blank pages of Olive Hannum’s copy of the Floral Album trades on the idea that during this period a young woman was, like a flower, in bloom, and that floral tributes were the most fitting ways to honor her. For instance, somebody named Amanda Dobs contributed to Olive’s album a poem titled “The First Rose of Spring.” In 1841, in “To Miss Olive N. Paine, On her Album,” a D. McCurdy identified the album on which he or she wrote as a “storehouse of wild flowers.”

Publisher

J. C. Riker, New York

Collection

Accession Number

A/H2468

Additional Information

Place of creation: Printed in New York; the album’s blank pages were filled up in Provincetown, Massachusetts.

Details on creation: Possibly engraved by Edward Gallaudet, 1809–1847 and later scrapbooked by American Olive Nickerson Paine, later Olive Nickerson Hannum, 1820–1894.

Provenance: Acquired from Dan Casavant Rare Books, 2015