Creation Date

1826

Medium

Genre

Description

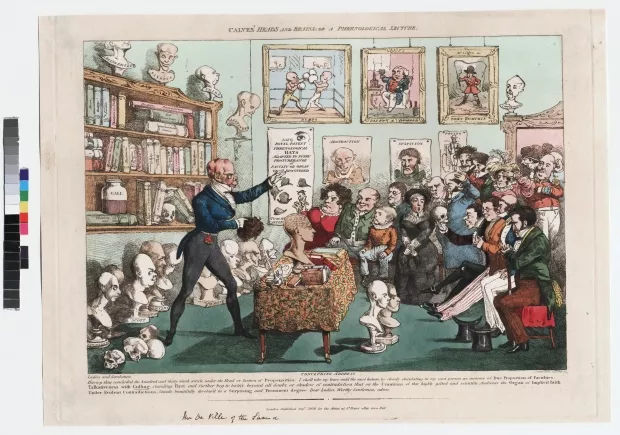

A phrenologist lectures to a seated audience. The writing below the print identifies the phrenologist as James De Ville; however, M. George posits that the phrenologist is George Combe (George 606). He holds a wig in his right hand and gestures to the audience with his left. The phrenologist's head has several bumps, echoing and surpassing the shapes of the phrenological casts scattered around the room. Note especially the sharp contrast between the prominent bumps on the phrenologist’s skull and the idealized plaster cast of De Ville displayed in the lower center of the image. Also noteworthy among the casts are busts of Gall, Spurzheim, and Shakespeare. Other casts portray organs and mock-organs instead of historical figures: “gazing faculty,” “slyness,” “pride,” “sleepiness,” and “consequence.” A skull labeled “Thurtell” can also be seen in the lower left corner. Posters cover the wall: one advertises hats; another puns on "bumps"; others illustrate mock-phrenological characteristics such as "abstraction" and "suspicion." The bookshelf behind the phrenologist contains works by Lavater, Moore, Combe, and Aristotle, as well as treatises on "Self Knowledge," "Bells Brain," "Gold Making," "Magic," and the "Philosopher's Stone." Members of the audience alternately watch De Ville and each other. One man holds a skull, several others feel their heads.

Calves’ Heads can also be divided between the left half of the image, from which the phrenologist and the phrenological casts gaze at the audience, and the right half of the image, from which the audience’s gaze is dispersed between the phrenologist, his props, the other audience members, and each audience member's own body. This contrast also associates phrenology with sculpture and literature (with such various sources in mind as Aristotle and “Lectures on Nothing”) and the audience with posters, politics, and the crowd. It is noteworthy here that the pseudo-phrenological characteristics associated with the left side of the image are the “gazing faculty,” “slyness,” and “pride,” while the right side of the image shows “consequence,” “prying,” and “suspicion.”

The expansive labeling of phrenological items in this print evokes the large public debate regarding the usefulness of phrenology occurring in the first half of the nineteenth century. This image also features a large amount of casts; like the mapped head, the phrenological cast was associated with phrenology from its earliest publications throughout the nineteenth century. The Phrenological Journal and multiple periodicals identify James De Ville as extremely involved in both the collection and display of such casts (Phrenological Journal 262ff). Finally, social caricatures such as Calves’ Heads and Brains (1826) complicate the phrenological gaze by associating the “gazing faculty” with suspicion, deception, education, and commercialism.

Satirical caricatures of the phrenological lecture both poked fun at the pseudo-science's claim to an infallible "reading" of the subject and revealed the extent of its popularity. The expansive labeling of phrenological items in this image also evokes the large public debate regarding the usefulness of phrenology occurring in the first half of the nineteenth century. By placing the skull of John Thurtell on the floor of the image, the caricaturist records the public’s interest in using phrenology to identify criminals, an interest also documented in news articles and phrenological tracts like The Phrenological Journal (“Further Particulars of Thurtell, &c.”; Phrenological Journal 297ff). The application of phrenology to a photographic archive of criminals is well documented by Allen Sekula (11ff).

The contrast between the phrenologist’s—perhaps De Ville’s—bumpy skull and the idealized cast of De Ville echo the use of key historical figures as types in phrenological writing: Combe, for example, compares the large “animal organs” and small “organs of the moral sentiments and intellect” of Pope Alexander VI (15th C) to the large “organs of the moral sentiments and intellect” of Philipp Melancthon (16th C). In doing so, he seeks to contrast the former’s disposition towards "animal indulgence” and tendency “to seek gratification in the directest way” with the latter’s exemplary role as a “great and virtuous reformer” (Combe 30).

A poster advertising “phrenological hats adapted to every protuberance of faculty or organ” reminds the viewer that phrenological lectures, such as those given by De Ville, were commercial as well as educational enterprises. Finally, the label provided for the image—the conclusion to the lecture—calls into question the truth behind phrenology’s claims. The caricaturist’s phrenologist ends his lecture by claiming that, “on the craniums of this highly gifted and scientific audience the organ of implicit faith under evident contradictions, stands beautifully develop'd to a surprising and prominent degree.”

Social caricature satirized popular trends not simply in order to entertain but also to inform or alter public opinion. Caricatures of phrenology taught the “clinical gaze” by illustrating the pseudo-science’s usefulness (or lack thereof) in the interpretation of human appearance and—because the exterior or visible was here equated with the interior or unknown—in the reading of human character ( Foucault 103ff).

Copyright

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University. Copyright, 2009.

Collection

Accession Number

826.9.0.1

Additional Information

Bibliography

"Advertisement 2 -- no Title." Christian Register and Boston Observer (1835-1843) May 13 1843: 76. ProQuest. Web. 1 May. 2009.

“Article VI.” American Phrenological Journal. (1841): 185-9. Print.

Combe, George. Outlines of Phrenology. 5th ed. London: Longman & Co., 1835. Print.

Cowling, Mary. The Artist as Anthropologist: The Representation of Type and Character in Victorian Art. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1989. Print.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of the Clinic. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Routledge, 2003. Print.

Fraser, Angus. “Thurtell, John (1794–1824).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Web. 30 Apr. 2009.

“Further Particulars of Thurtell, &c.” Examiner 18 Jan. 1824: 40-41. Print.

George, M. Dorothy. Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum. Vol. 10. London: Oxford UP, 1952. Print.

H., A. “Letter.” The Gentleman’s Magazine Sept. 1825: 216-7. Print.

H., R. “Phrenology.” Republican 14.3 (1826): 82-6. Print.

Karp, Diane. "Madness, Mania, Melancholy: The Artist as Observer." Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 80.342 (1984): 1-24. Print.

McLaren, Angus. "Phrenology: Medium and Message." The Journal of Modern History 46.1 (1974): 86-97. Print.

Patten, Robert. "Conventions of Georgian Caricature." Art Journal 43.4 (1983): 331-8. Print.

---. George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art: 1792-1835. Vol. 1. Rutgers UP, 1992. Print.

The Phrenological Journal and Miscellany Vol. 3. (August, 1825 – October, 1826): Edinburgh, 1826. Print.

“Phrenology.” Literary Gazette Sept. 1829: 599.

Sekula, Allen. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39 (1986): 3-64. Print.

Spencer, Frank. History of Physical Anthropology. New York: Garland Pub., 1997. Print.

Stafford, Barbara Maria. Body Criticism: Imagining the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991. Print.

Stafford, Barbara Maria. "From 'Brilliant Ideas' to 'Fitful Thoughts': Conjecturing the Unseen in Late Eighteenth-Century Art." Zeitschrift fur Kunstgeschichte 48.3 (1985): 329-63. Print.