Creation Date

1791

Height

38 cm

Width

54 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

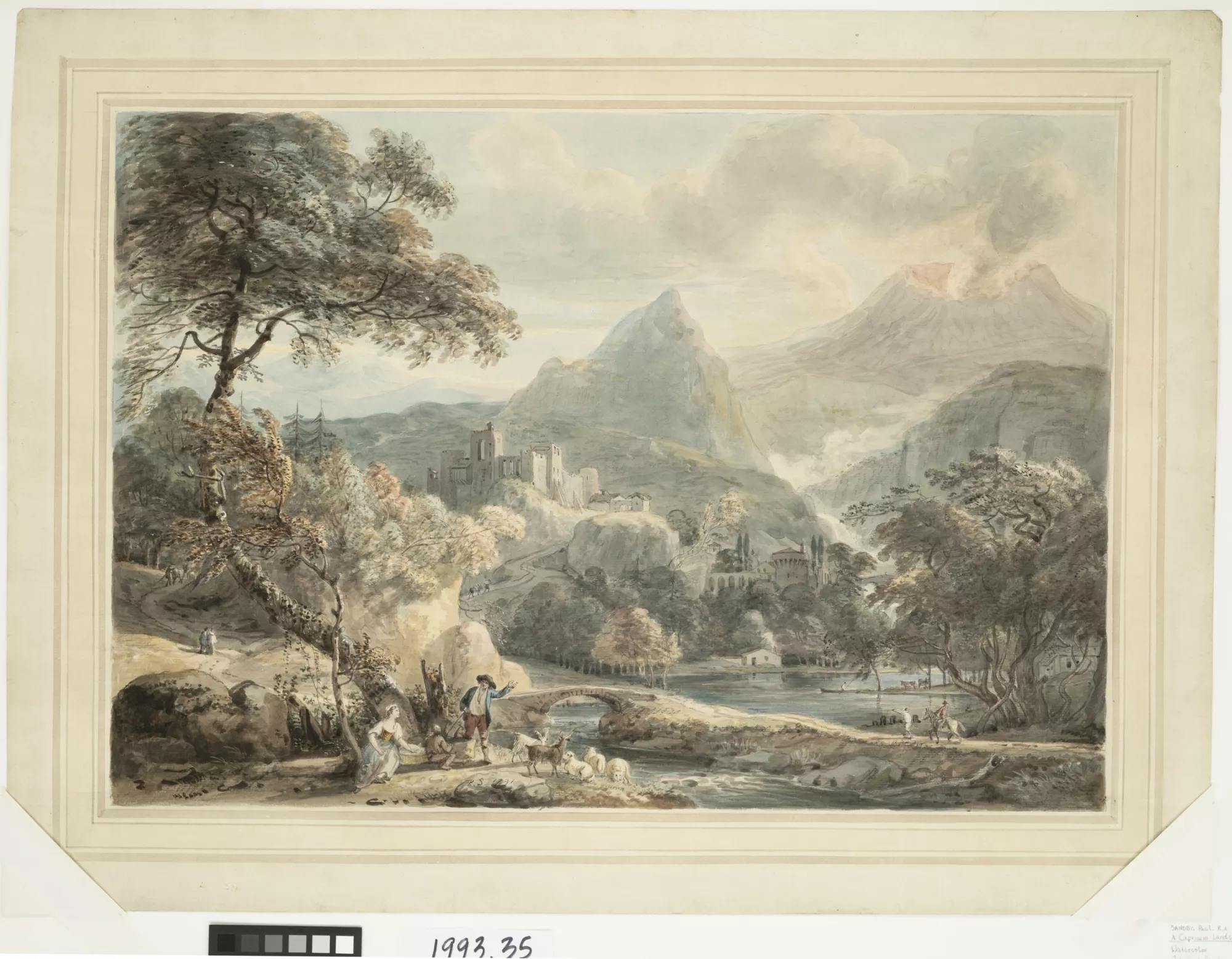

As noted by curator Andrew Stevens (Chazen Museum, University of Wisconsin), this “painting is a pastiche of second-hand Italianate architecture and geography imagery supplemented with the artist's own knowledge of Welsh mountain vistas. It is not based on a particular place.” Sandby was never in Naples, but in the 1770s he purchased a group of Neapolitan paintings from the Anglo-Italian artist Pietro Fabris and published these in a series of aquatints, Views in and Near Naples (1777-82). Sandby’s fame rests partly on his pioneering development of aquatint, a print medium especially suited for reproducing watercolors. Sandby’s first series of aquatints, Twelve Views in Wales (1775), was based on his own sketches made in Wales the early 1770s. The pastoral grouping of the gesticulating goatherd and (presumably) his family, in the left foreground of this picture, is itself a hybrid of Welsh and Italian elements, though the female figure specifically recalls Fabris’s studies of Neapolitan laboring-class costume, as do the man and panniered donkey ascending the road to the castle (use the magnifying glass tool to see these figures). The equestrian figure is evidently a tourist or stranger being shown the way. The causeway and bridge extending from these figures diagonally across the middle ground are echoed by a series of increasingly dramatic mountain bridges below the castle and just to the right of the town. Sandby was one of the first landscape artists to tour Wales, pioneering a practice that became very popular from the late 1770s. This composition, particularly the rugged conical hill and steep gorge in the center, shows him still drawing on his own original sketches twenty years afterward. The architecture, particularly the aqueduct and round tower above the lake, suggest the Roman campagna more than Naples, and may be inspired by a set of Italian landscapes that Sandby purchased from another artist, Richard Wilson. Unlike Palmer’s Street of Tombs, which accompanies this painting in the exhibit, "Volcanoes, Science, and Spectacle in the Romantic Period," Sandby’s watercolor uncouples the Italian volcano from its archaeological setting, creating a p,astiche that frees him to emphasize the raw power of the dynamic sublime. [NH]

In this watercolor, Sandby is primarily concerned with depicting the sublime in his portrayal of an Italian landscape: the mountains and smoldering volcano invoke a sense of awe, while the grey smoke, bending trees, and quivering leaves suggest a silent, unseen danger—liable to burst forth and threaten the safety of the tiny human figures scattered about the countryside.

With its elements of the sublime and picturesque, Sandby offers us a view of volcanoes that is typical for the 1790s. The scene is imaginary, and so the observer can see in this painting the early Romantic perception of volcanoes. Sandby’s combination of dark gray colors (for smoke) and dark red colors (for the large caldera), as well as the depicted motion of a strong wind, creates a sublime view of the volcano. Like other early Romantic artists, Paul Sandby is concerned with evoking fear and awe when depicting volcanoes. [MH]

A map maker turned landscape painter, Paul Sandby was a founding member of the Royal Academy. His subsequent fame launched his landscape career. He is most famous for his watercolors and aquatints, and A Capriccio Landscape was created to showcase his watercolor talent.

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison