Creation Date

1821

Height

4 cm

Width

18 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

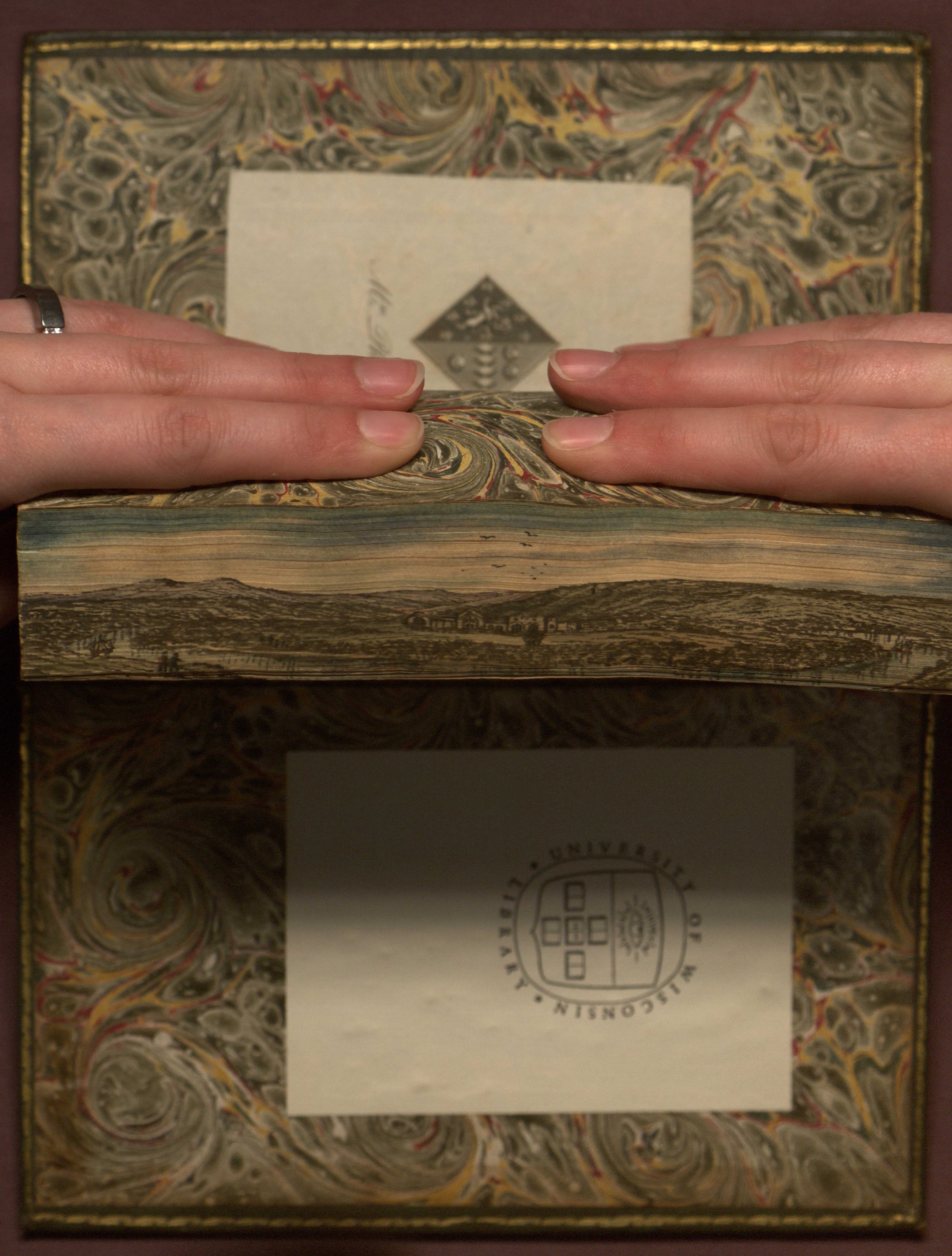

The fore-edge painting on the first volume of Sir Walter Scott's Kenilworth, probably depicts Kenilworth Castle; and the painting on the third, Cumnor Place; with both buildings pictured in the midst of a vast rural landscape. The painting on the fore-edge of the second volume would then evoke the busy urban and political world to which Kenilworth and Cumnor belong, despite their seclusion. As their location on the fore-edges of Kenilworth implies, and these tentative identifications confirm, these paintings are poised between three worlds, each of which can be taken as their primary subject: the world conjured by the paintings, the imagined world of Scott's novel, and the historical past—each of which offers a view of Kenilworth and Cumnor Place not entirely congruent with the others.

Apart from their intrinsic charm, the appeal of these paintings derives from the mismatch between their tiny canvases and the vast world they evoke; the rapidity with which the latter appears each time the pages of Kennilworth are fanned; and the implied parallel between the emergence of painterly, literary, and literary-historical worlds. Arguably they thematize and celebrate this production and multiplication of worlds, while evoking a cultural realm hidden from the mundane world that nevertheless provides its canvas.

A conventional edge-painting uses one of the edges of a closed book as a canvas—usually the edge furthest from the binding or spine (the fore-edge), but sometimes the top or bottom. They are therefore visible when the book is closed. But first in the middle of the seventeenth century, and then more commonly in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries, artists painted just inside the outer-edge, creating an image that appears only when the pages of the book are slightly fanned. The fore-edge paintings on the three volumes of Kenilworth by Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832), which are held in Special Collections at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, belong to the second category.

On each of these cramped canvases, which even when fanned are more than four times longer than they are high, the artist has painted a surprisingly detailed view of an expansive landscape. On the first volume, the prospect is discreetly divided into three horizontal bands. At the top of the design, white, wispy clouds are seen against a blue sky. Beneath them, a band of mountains and rolling hills stretches from the left- to the right-hand side of the fore-edge. The mountains are colored a dull-blue and gray, which emphasizes their height against the green of the hills. A mansion is nestled amongst the hills on the right, which has faded yellow walls, blue rooftops, and countless windows. The hills on the left-hand side of this middle band are colored with brown, gray, and green lines, creating the impression that they have begun to erode. The lowest band of this fore-edge painting is the smallest: it provides a glimpse of several men riding horseback along the shore.

The fore-edge painting on the second volume, which is much better preserved than the first, is also divided into three horizontal bands. At the top of the design, wispy white clouds are seen against a blue sky in which five birds can be seen. Beneath them, forming the middle band, there is a mountain, with a dirt road winding up its sides; large green hills; and buildings, which become more numerous as one's gaze moves from the left to the right-hand side of the painting. This view of an urban rather than rural England is extended in the lowest band, which depicts docks, as well as sailboats on the water.

The fore-edge painting on the third volume of Kenilworth forms two broad horizontal bands. It provides a much closer look at the landscape than either of the previous paintings. In the upper-half of this image, immediately above the horizon, a bank of clouds rises to a strip of dark-blue sky. The orange-brown tint carried by the strands of white cloud suggests that we are looking at a moment just before the sun rises above (or just after it has fallen below) the horizon. At the centre of this strip of sky, a flock of birds can be seen, flying from the horizon towards the viewer. The lower half of the design depicts a rural environment, similar to the one seen in the first fore-edge painting. Gray-blue mountains appear on the left-hand side of the design, at a great distance from the observer. As one's gaze moves from the far to the near, and from the left to the right-hand side of the image, the mountains are replaced by rolling green hills.

At the foot of the hills, almost in the centre of the painting, and immediately below the flock of birds, is a large, rambling, group of connected buildings, which are shown only in silhouette. Although the details are not clear, the buildings include what might be a chapel, with its apse facing the viewer, and a rectangular, crenelated structure, with an arched-gateway to the left. These edifices are linked by a low wall with two arches or windows, while smaller buildings cluster to the right of the second and perhaps also to the left of the first building. A river curves around the grounds of this impressive countryseat. It winds from the hills to the left, towards the viewer; then almost cuts out of the painting near the centerline, before looping back into it on the right-hand side. The surface of the river is dotted with sailboats, with two large craft visible, with sails unfurled, at the far-left and far-right hand side of the painting. On a prominence to the left, near the lower-border of the design, two men have stopped to survey the scene.

Scott's Kenilworth is centred on the life of Amy Robsart (1532-1560), who in "real life" died by falling down a flight of stairs. At the time, rumours began to circulate that her husband, Robert Dudley, the Earl of Leicester, and a favourite of Elizabeth I had murdered her. And these rumours, propagated by the publication in 1584 of The Copie of a Leter, wryten by a Master of Arte of Cambrige, which stated baldly that she had been murdered, inspired a vigorous popular tradition. This tradition provides the starting point for Scott's narrative, whose primary source for the relation between Robsart and Dudley was Elias Ashmole's Antiquities of Berkshire (1: 149-54). Modern historians are less confident that Dudley murdered his wife (Sidney 13; Doran 42-4).

The fore-edge paintings represented in this exhibit are designed to dazzle and surprise the viewer (Weber 18), while adding to the value of the book as a physical object. They provide a visual supplement to Scott's Kenilworth, advertising by mirroring the world it conjures and the world it re-presents, while foregrounding some of the book's main themes.

Like all fore-edge paintings, those adorning this copy of Kenilworth are decorations, which add to the value and visual appeal of the book as a physical object, in part by individualizing it. They represent late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century developments in the art of fore-edge painting, while also evoking a romantic stage in the history of book collecting, which was at its height in the years between 1809 and 1832 (Jackson 208-17; O'Dwyer). For these collectors, the allure of such paintings was no doubt increased by the fact that they remain hidden, unless one knows that the pages of their host must be fanned.

The paintings play with light and colour to evoke mood and atmosphere, in ways influenced by Romantic landscape painting. But here these effects are heightened because, unlike more conventional paintings, the viewer has an active role in their appearance and, moments later, their disappearance. This gives the paintings (and their canvases) the character of a fleeting impression, in relation to which the observer is both active and passive, and which appears only in a particular perceptual environment (composed by the artist's work; the book's leaves; the observer's hand, eye, and mind; and the presence of light).

This fleeting impression is not entirely dissimilar from the phenomena described by Wordsworth in A Guide through the Lakes (first published in 1810), such as the "Island" which, like the fore-edge paintings, seemed suddenly to spring into being as if "newly-created" (108-10). Despite its apparent reality, the Island is an optical illusion (a natural painting), which, again like our fore-edge paintings, will vanish when the relations between mind, body, and world that have brought it into being begin to change. In contrast to the subject of modernity, which stands apart from the body and the world (Taylor 159-76), the fore-edge paintings and Wordsworth's natural painting could be considered as offering, respectively, a modest experience and an ambitious allegory of the embodied self (an active element in a system that exceeds it) that is central to Romanticism.

Locations Description

Kenilworth Castle, in Kenilworth, Warwickshire, England, is a ruined castle is northwest of London, six miles south of Coventry, and forms the site for some of the key scenes in Scott novel. It is likely that this is the "mansion" hidden in the rolling hills of the fore-edge painting on the first volume of Scott's Kenilworth.

Cumnor Place, in Cumnor, Oxfordshire is building that was first a Benedictine Retreat, then a manor house, before being demolished in 1810. It was here that, according to Scott, Amy Robsart was virtually imprisoned and where she was murdered. According to local legend, the house was demolished owing to the troublesome presence of her ghost. It is possible that this is the building pictured on the fore-edge of the third volume. For details of the historical Cumnor Place see Bartlet, An Historical and Descriptive Account and Inman, "Amy Robsart ad Cumnor Place."

Collection

Accession Number

1268062-1268064

Bibliography

[Anonymous]. The copie of a leter, wryten by a Master of Arte of Cambrige, to his friend in London, concerning some talke past of late betwen two worshipful and graue men, about the present state, and some procedinges of the Erle of Leycester and his friendes in England . . . [no imprint], 1584.

Ashmole, Elias. The Antiquities of Berkshire. 3 vols. London: E. Curll, 1719.

Bartlett, Alfred Durling. An Historical and Descriptive Account of Cumnor Place, Berks, with Biographical Notices of the Lady Amy Dudley and of Anthony Forster, Esq. . . .. Oxford and London: John Henry Parker, 1850.

Doran, Susan. Monarchy and Matrimony: The Courtships of Elizabeth I. New York: Routledge, 1996.

Inman, Peggy. "Amy Robsart and Cumnor Place," Cumnor Historical Society. [http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/external/cumnor/articles/inman-robsart.htm, accessed 14 October, 2013].

Jackson, H. J. Romantic Readers: the Evidence of Marginalia. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005.

O'Dwyer, Edward John. Thomas Frognall Dibdin: Bibliographer & Bibliomaniac Extraordinary, 1776-1847. Pinner, Mddx.: Private Libraries Association, 1967.

Sidney, Phillip. Who Killed Amy Robsart? Being Some Account of Her Life and Death. With Remarks On Sir Walter Scott's "Kenilworth." London: E. Stock, 1901.

Taylor, Charles. Sources of the Self: The Making of the Modern Identity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Weber, Carl J. Fore-Edge Painting: A Historical Survey of a Curious Art in Book Decoration. Irvington-on-Hudson, NY: Harvey House, 1966.

Wordsworth, William. A Guide through the District of the Lakes in the North of England, with A Description of the Scenery, &c. For the Use of Tourists and Residents. Fifth edition, Kendall: Hudson and Nicholson, 1835.