Creation Date

1841

Height

33 cm

Width

63 cm

Medium

Genre

Description

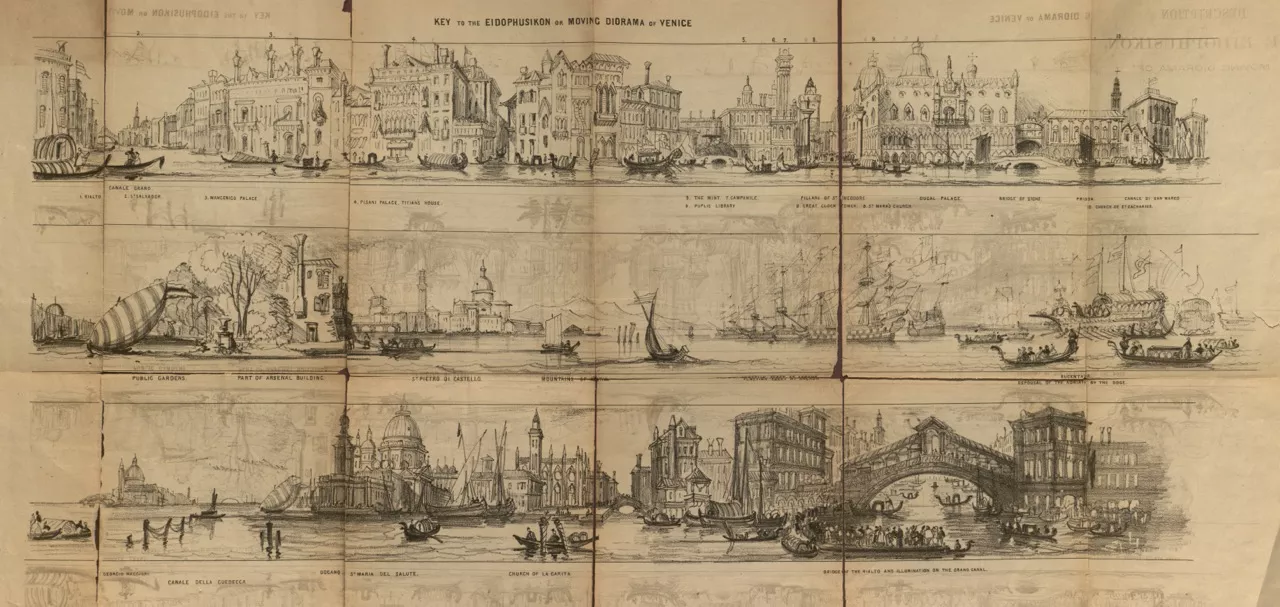

This image provides a simulation (a linked sequence of picturesque views) of a simulation (the Diorama of Venice) of a tour of the actual City of Venice and its environs. The relation of the first to the second, and of the second to Venice itself, is that of a copy to a more complex original; yet both copies are works of art in their own right that take on the role, albeit in different ways, of introducing their respective originals. Although, the primary subject of the Key is the "Moving Diorama of Venice," it is difficult to disentangle this from the primary subject of that Diorama, namely the City of Venice itself.

With regard to the first subject, the Key re-presents, identifies, and arranges in sequence the picturesque views that comprise the "Diorama of Venice," while also evoking the temporal, kinetic, and atmospheric effects that texture the moving-diorama's virtual reality, and for which that medium was famous. It acts as précis of, guide to, and commentary on its proximate original. But this introduces the second subject. By visually quoting from the Diorama, and by naming the elements and specifying the day it re-presents (the Espousal of the Adriatic coincided each year with the Feast of the Ascension), the Key anchors its parade of scenes (and those of the Diorama) in the actual City of Venice, at the Feast of the Ascension, some time in the preceding century.

The journey I have been tracing—from representation to simulation to reality—is akin to the one offered by the Diorama to its customers, even though they could complete its last leg only in imagination. As Oetermann observes, "The dioramas seemed to offer a quick and easy substitute for travel, almost as if they were not pictures of distant places but the distant places themselves, now right next door: a paradox that naturally aroused people's curiosity and made them willing to pay the high price of a ticket" (79).

Owing to the cost of travel, most were unable to compare the virtual reality they had entered with the actual reality it supposedly reproduced. In the case of the "Moving Diorama of Venice," the reality it presented was in an important sense inaccessible: Napoleon's forces crushed the Venetian republic in 1797, and its state ship destroyed in the following year (Plant 37). As the Introductory and Historical Description makes clear, the view offered by this diorama is of Venice in the last century, before its decline. But even if the Diorama's patrons were able to journey to the reality represented, they might have been disappointed by the relative scarcity of the commodities so readily available in the diorama: intense experience, overwhelming spectacle, and a sense of enchantment.

These observations bring us to another subject of the "Key to the Eidophusikon or Moving Diorama of Venice," namely the representation (rather than the reality) of Venice. The Key frames its audience's experience of the Diorama, while the Diorama frames their imagined (which for most members of the audience will also be their first) experience of Venice. Even for wealthy members of the audience, such experiences are likely to precede and to that extent also shape, their actual experience of Venice. Key and Diorama accordingly take their place within the long history of representations of Venice, which for nineteenth-century audiences takes its lead from Piozzi, Radcliffe, and Byron, amongst others (Tanner 17). Indeed, the mix of enchantment, melancholy, and spectacle evoked by the Key and Diorama, is as much an illustration of Byron's Venice as it is of the city itself:

I stood in Venice, on the Bridge of Sighs;

A palace and a prison on each hand:

I saw from out the wave her structures rise

As from the stroke of the enchanter's wand:

A thousand years their cloudy wings expand

Around me, and a dying Glory smiles

O'er the far times, when many a subject land

Look'd to the winged Lion's marble piles,

Where Venice sate in state, thron'd on her hundred isles!

("Childe Harold's Pilgrimage," Canto IV, lines 1-9)

This foldout guide to the "Moving Diorama of Venice" is divided into three large panels showing a series of "highlight" views of Venice, as if seen from a passing gondola. Ignoring the distance that in the real Venice divides them from each other, each view folds seamlessly into the next until the last scene on the right brings us to the first scene of the following panel, creating the impression (as our gaze travels from left to right, and then from left to right again) that we are watching a moving panorama or, better still, being taken on a virtual tour of Venice. The tour ends in the lower right-hand corner of the design, which brings us back to the beginning of the first panel (the Rialto bridge).

The six black lines running from the left to the right-hand side of the page define the upper and lower borders of the panels, while leaving their left- and right-hand sides unframed. These same lines mark the upper and lower margins of four thin strips, one above and another below each panel, which create the impression that we are viewing the moving-scene through a paper window-mount (even though the left- and right-hand wings of the mount have been removed). The names written on these otherwise blank-strips, immediately beneath the scenes they identify, help viewers orient themselves, by presenting the tour as a parade of picturesque views (which matches the sequence of fourteen views presented in the moving diorama).

The first panel opens on the Canale Grande, with a backward glance at the Rialto Bridge where, one presumes, the tour began. In the distance it is still early morning—the gondolas are empty, tied to their moorings—but as one's gaze moves towards the foreground of this prospect, the day advances with us and the scene comes alive: a man is being ferried from the left to the right-hand side of the canal; another, on board a covered gondola, seems about to begin the day's business. As the tour proceeds (moving down the Grand Canal towards St Mark's Square) we see on the left bank, first the Macenico Palace (probably the Palazzo Mocenigo, Byron's home in Venice from 1818-19), with its chimneys reaching high into the air; then the Pisani Palace (incorrectly nominated by the artist as Titian's house); past a procession of unidentified palazzos, until we reach the Campanile, Basilica di San Marco, Pillars of St. Theodore, Ducal Palace, and the Prison. Venice is now bustling—St. Mark's Square is filled with people; others crowd onto the top of the bridge in front of the Bridge of Sighs; and the water near the shore is cluttered with gondolas and sailboats. The prospects we have been passing are so detailed that many of the names have been keyed with numbers placed on the upper margin of the panel, to help distinguish highlights from lesser buildings and to identify some that are partially obscured, such as St. Salvador and the Church de St. Zacharius.

The next panel takes us further along the coast, from the sights of San Marco to those of Castello. The dome of the Basilica can still be seen on the left, but now only at a distance, partially obscured by a row of buildings. The weather has changed, and the wind is buffeting a small boat—its mast and striped sail lean at an angle of 45 degrees to the water. This maritime prospect is followed by a view of the Public Gardens, the Arsenal Building (part of Venice's famous ship-building works), the Basilica di San Pietro (in the middle ground of the design), and then a row of mountains far in the distance. Out in the lagoon, to the right of these last three scenes, the Venetian fleet is at anchor. And still further to the right, the "Espousal of the Adriatic" has begun. The Doge is seated on a throne on the prow of the Bucentaur, the state ship of the Venetian republic, as he celebrates the sovereignty of Venice over the Adriatic (Smedley 1: 63), watched by an audience on board a fleet of gondolas.

Our journey past the Venetian fleet and Doge's galley has taken us out into the lagoon; but by the beginning of the third panel, our gondola has circled back towards San Marco. With the sun slipping below the horizon, we pass in succession San Giorgio Maggiore; the Giudecca Canal (which divides the sestiere of Giudecca from Dorsoduro); and then the Dogana da Mar (Venice's old Customs house), with Santa Maria del Salute immediately behind it, at the entrance to the Grand Canal. Now travelling back up the Grand Canal, our attention is drawn to Santa Maria della Carità (on the left-hand side of the canal, near when the Academia Bridge now stands) before arriving at the Rialto Bridge. Although this is where our tour began, the scene is very different: night has now fallen, and the balconies, terraces, bridge, and gondolas that clutter the canal are filled with people enchanted by the gaily-illuminated scene.

The image functions as a guide and orientation device for those entering the "Diorama of Venice." For those uncertain whether to buy tickets, it functions as an advertisement for and précis of the same show; and for those who have already experienced what the "Diorama of Venice" has to offer, it is useful as memento, mnemonic device, and talking point.

"Moving Diorama of Venice"—the image offers a key to this diorama, which was exhibited in Glasgow in 1841 and in Edinburgh the following year, where it was accompanied by a view of Lake Geneva.

"View of Lago Magiore"—a panoramic view, no doubt with atmospheric lighting effects, shown alongside the "Moving Diorama of Venice" when it was exhibited in Glasgow.

"Espousal of the Adriatic"—a ceremony celebrating the sovereignty of Venice over the Adriatic.

"Eidophusikon; or, Various Imitations of Natural Phenomena, represented by Moving Pictures"—a three-dimensional, multi-media show, often described as the earliest moving-pictures, which was first exhibited by Loutherbourg in 1781 (Altick; Baugh; McCalman; Otto).

The use of the word Eidophusikon in the title of the Key places the "Diorama of Venice" within a modern history of moving pictures, virtual realities, and multi-media spectacle, that arguably begins with Philippe de Loutherbourg's exhibition in 1781 of the "Eidophusikon; or, Various Imitations of Natural Phenomena, represented by Moving Pictures" (Otto 163-72; Huhtamo 103-4). Although the "Diorama of Venice" is not strictly speaking an Eidophusikon show, at least in the sense in which the word was used by Loutherbourg, the allusion advertises the former's reproduction of some of the latter's effects: the evocation of atmosphere; multi-media spectacle; and "virtual realities that appeared to be in motion, as if animated by an uncanny life of their own" (Otto 163).

In its immediate context, the Key addresses an audience "trained" by Romanticism to appreciate atmospheric mood, dreamy mystery, and picturesque beauty, inviting them to take part in a modern form of virtual tourism, which is able create the sensation of travelling not just to other locations but backward and forward in time. For those willing to embark on this journey, it becomes tour guide and compass—roles that give it a place within the modern history of virtual reality and of its tangled relation with the real.

Locations Description

Venice, Italy is the subject of the Key and Diorama.

Lake Maggiore straddles the border between Italy and Switzerland, stretching 65 kilometres, from Sesto Calende in the south to Locarno in the north.

The "Diorama of Venice" was exhibited in the Monteith Rooms, Buchanan St., Glasgow.

Collection

Accession Number

F36V IN Cutter

Additional Information

Bibliography

Altick, Richard D. The Shows of London. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1978. 117–27.

[Anonymous]. "Gordon's British Diorama . . . Now Open: An entirely New Pictorial Exhibition being a Moving Diorama of the City of Venice and its Environs . . ." [Advertisement]. Caledonian Mercury 17 November 1842.

Baugh, Christopher. "Philippe de Loutherbourg: Technology-Driven Entertainment and Spectacle in the Late Eighteenth Century." Huntington Library Quarterly 70.2 (2007): 251–68.

Byron, George Gordon Byron, Baron. Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Lord Byron: The Major Works. Ed. Jerome J. McGann. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. 19-206.

Huhtamo, Erkki. Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013.

McCalman, Ian. "The Art of De Loutherbourg's Eidophusikon." Sensation & Sensibility: Viewing Gainsborough's "Cottage Door." Ed. Ann Bermingham. New Haven, CT: Yale Center for British Art, 2005.

Oettermann, Stephan. The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium. New York: Zone Books, 1997.

Otto, Peter. Multiplying Worlds: Romanticism, Modernity, and the Emergence of Virtual Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Plant, Margaret. Venice: Fragile City 1797-1977. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

Smedley, Edward. Sketches from Venetian History. 2 vols. New York: J. & J. Harper, 1832.

Tanner, Tony. Venice Desired. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

Timbs, John. Curiosities of London, Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis. 1855; London: Virtue, 1867.

Wood, R. Derek. "The Diorama in Great Britain in the 1820s." History of Photography 17.3 (1993): 284-95.