Creation Date

1 December 1834

Medium

Genre

Description

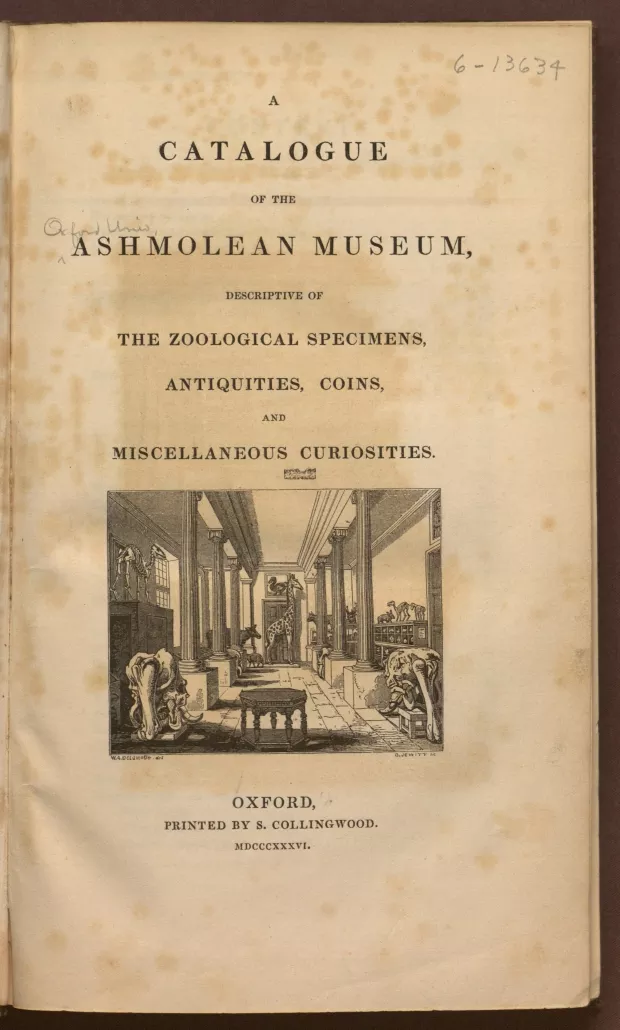

The engraving depicts the lower room of the “Old Ashmolean” building at the University of Oxford. Various natural specimens, including a giraffe and a dodo, are evident, as well as two groups of large bones in the foreground. A small table is placed prominently in the center of the image between two parallel rows of ionic columns. Cabinets of specimens line the right hand side of the room. The engraving depicts the lower room of the “Old Ashmolean” building at the University of Oxford. The exhibit on display in this particular room appears to be made up exclusively of zoological specimens.

Placed on the facing page to Frederick Mackenzie’s imposing drawing of the grand façade of the “Old Ashmolean,” this much smaller and almost cartoonish representation of the interior of the museum is the focal point of the title page. Although the title of the book, printed directly above the engraving, announces a catalog Descriptive of the Zoological Specimens, Antiquities, Coins, and Miscellaneous Curiosities, the image seems to depict only those of the zoological variety. This focus on the diversity of the natural world recalls the early character of the collections formed in the late 1600s by John Tradescant and his son and donated to the University of Oxford by Elias Ashmole in 1683: "Contemporaries apparently regarded the elder John Tradescant and his son as seventeenth-century Noahs who had gathered together a microcosm of the entire world, for they dubbed the house at South Lambeth 'Tradescant’s Ark' " (Swann 29). This impression is confirmed in an earlier account by a traveler named Peter Mundy who visited the Ark in 1635 and recorded some of what he saw there:

[B]easts, fowle, fishes, serpents, wormes (reall, although dead and dryed), pretious stones and other Armes, Coines, shells, fethers, etts. of sundrey Nations, Countries, forme, Coullours; also diverse Curiosities in Carvinge, painteinge, etts., as 80 faces carved on a Cherry stone, Pictures to bee seene by a Celinder which otherwise appeare like confused blotts, Medalls of Sondrey sorts, etts. (Swann 1)

Delamotte’s drawing presents an image of the Ashmolean that reflects the diversity of Mundy’s catalog. While the skeleton on the cabinet in the upper left of the image and the piles of bones in the foreground are rendered with a degree of detail that suggests the scientific and academic ambitions of the museum’s collections, the other specimens seem to be drawn with a less exacting hand. The giraffe is particularly striking—although it is meant to represent a stuffed specimen, it appears alive, patiently standing at the end of the hall of its own volition. Beneath the giraffe, a quadruped of some variety looks as if it has walked partially behind the column that obscures its head. The skeletons or skulls placed between the columns at the far end of the room are similarly disordered and give the impression of a multitude of unknown entities populating the shadows and invisible spaces of the room. The cases which line the wall on the right side of the image are indistinct in a manner that renders them similarly abstract—they suggest a wealth of material cluttering various cubbies and shelves, but it is impossible to tell what the cases might actually contain. Notably absent from this image are the more “miscellaneous” and curious aspects of the museum’s collections: other than the table in the center of the image and, of course, the structure of the building itself, none of the specimens visible in the room are man-made. The title page of the book suggests that these other aspects of the collection were still present in the recently reorganized museum; however, as they are not included in the illustration, Delamotte's engraving seems intended to highlight the natural specimens that were emerging as the centerpiece of the Ashmolean collections.

Locations Description

The Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford is the oldest public museum in Britain (MacGregor 5). It was founded in 1683 by the gift of Elias Ashmole (1617-1692), who bestowed upon the University both the already famous collection of natural and man-made curiosities known as Tradescant’s Ark, as well as his personal collections of coins, books, and manuscripts.

Renown for the collections amassed and curated by John Tradescant and his son (also named John) was widespread in the 1600’s:

The Tradescant collection, located at the Tradescant family home in South Lambeth, was a "must see" attraction for nearly half a century. In 1660 the headmaster of Rotherham Grammar School declared that London was "of all places . . . in England . . . best for the full improvement of children in their education, because of the variety of objects which daily present themselves to them, or may easily be seen once a year, by walking to Mr. John Tradescants . . . where rarities are kept." (Swann 28)

While John Tradescant the Younger—who inherited the Ark from his father—also apparently intended that Oxford or Cambridge be the eventual home of the collections, it was Ashmole who arranged the transaction and the construction of a new building to house the museum (Swann 49). Although Ashmole did not attend the University of Oxford, he wrote of his regard for the institution in a 1683 letter to the Vice-Chancellor:

It has of a long time been my Desire to give you some testimony of my Duty and filial Respect, to my honoured mother the University of Oxford, and when Mr. Tradescants Collection of Rarities came to my hands, tho I was tempted to part with them for a very considerable sum of money . . . I firmly resolv’d to deposite them no where but with You. (qtd in MacGregor 16)

Ashmole’s movement to secure a permanent display site for the collections shows a definite interest in establishing his own fame relative to the Tradescants and the Ark:

By 1675 Ashmole was negotiating with officials at the University of Oxford, specifying that if he were to donate the rarities to the University, they should be housed in a new, purpose-built "Large Rooem, which may haue Chiminies, to keep those things aired that will stand in need of it." In October 1677 Oxford agreed to house the objects to be donated by Ashmole in a new building dedicated to scientific research . . . Ashmole fiercely guarded the new identity he was crafting for himself as the owner and donor of the Tradescants’ collection. (Swann 48-9)

While the Tradescant family portraits were hung “about the gallery walls as a permanent testimony to their achievement,” Ashmole, of course, was given the greater honor in the naming of the new museum (MacGregor 18).

Initially conceived as a scientific enterprise consisting of the museum as well as working laboratories and undergraduate classrooms, the museum originally displayed man-made and natural curiosities side-by-side. The museum was reorganized several times during the nineteenth century with a new conception of classification in mind. On November 2, 1870, John Henry Parker, the keeper of the Ashmolean, delivered a lecture to the Oxford Architectural and Historical Society praising the progress in classification that had been made over the century since the museum’s founding:

It [Tradescant’s Ark] was the earliest collection of the kind formed in England, and chiefly consisted of what are called curiosities, without regard to whether they were objects of Natural History—the works of God, or Antiquities—the works of Man, in the olden time. The collection, with the additions of Ashmole, included Birds, Beasts, and Fishes, especially the productions of distant countries, all that was comprised under the general name of "Rarities." Such was the general character of a Museum down to our own time . . . The University has wisely decided on separating this miscellaneous collection, and distributing it to the different departments to which each belongs. (Parker 4)

By the end of the nineteenth century, many of the initial specimens donated by Ashmole had either been lost or transferred to the recently opened Oxford University Museum of Natural History, with the Ashmolean retaining mostly archaeological specimens.

Copyright

Copyright 2009, Department of Special Collections, Memorial Library, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI

Collection

Accession Number

AM 101.O82

Additional Information

Bibliography

MacGregor, Arthur. The Ashmolean Museum: A Brief History of the Institution and its Collections. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2001. Print.

Parker, John Henry. The Ashmolean Museum: Its History, Present State, and Prospects. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1870. Print.

Swann, Marjorie. Curiosities and Texts. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2001. Print.