The Multiplicity of Blake’s Songs

Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1794) is almost certainly William Blake’s most commonly taught work. Teaching the Songs is complicated by the fact that it exists in so many different forms. According to G. E. Bentley, Jr., “The plates of Innocence and the combined Songs were arranged in thirty-four distinct ways” (386). Inevitably we teach using one of the relatively cheap facsimile editions, or we make do with the letterpress poems in our anthology and supplement that with images online. This is where the fun starts because the best place to get the images for the Songs is the online William Blake Archive, where we currently find four different copies of the Songs of Innocence (1789) and thirteen different copies of the combined Songs of Innocence and of Experience. This does not give students access to all extant copies of the Songs, but this is a pretty good sample, and the multiplicity itself makes a point to students about what Blake thought about the stability of a “finished” work. While any single copy of the Songs obviously functions as an artistic unity, no copy can claim to be the “last word” on the Songs. The ultimate version of Blake’s Songs is the composite reading of as many copies as possible, and while we may not hope to do that, we can do other things. In the following pages of this essay, I want to suggest why and how we might read “all” the Songs (more or less) in the classroom.

The multiplicity of the Songs is commonly recognized as both a problem and an advantage to teaching them. In their introduction to the MLA Approaches to Teaching Blake’s Songs (1989), Robert Gleckner and Mark Greenberg remark that “the Songs poses the problem of what, for Blake, constitutes a ‘book,’ as distinct from a collection of poems or an anthology” (xiv). They note that “Even ‘complete’ composite editions in color of one copy of the Songs present but one state of a work that Blake altered in color, visual design, and arrangement each time he printed and painted it,” and they commiserate with the “instructor (constrained by the chosen edition of work) [who] thus fixes a text that was continually changing in its author’s hands” (xvi). Nonetheless, in the collection’s essay on “Teaching the Variations in Songs,” Robert Essick extols “the rewards of a historical perspective on Blake’s composition, arrangement, and production of the Songs over a period of more than thirty-five years” because “We lose our sense of the individual copy as an unchanging and completely authoritative icon as it is recontextualized back into its material and temporal origins and seen as only one of many versions” (93). The problem in 1989 was the severely limited access to the basis for that “historical perspective on Blake’s composition” in the designs themselves; indeed, the advice of John Grant and Mary Lynn Johnson in the MLA volume on the availability of reproductions for classroom use suggests a sort of Blakean underground market in which images are available to those who have the right connections or enough money.

The situation has changed since 1989. With the thirteen combined Songs in the Blake Archive and the Blake Trust edition of Copy W ([c. 1825] the “King’s College” copy), students now have ready access to fourteen different versions of the Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Each copy is different, but some differences have a greater impact on our interpretation than others, and sequencing—the order of the poems in the collection—is especially important. I teach the combined Songs in four different classes, including a threshold course for English majors, a Romantics survey, a seminar exclusively on Blake, and a course I’ve developed on the Songs and Lyrical Ballads (1798). In all these classes, I use an approach to the various sequences adapted from Neil Fraistat’s The Poem and the Book (1985). In this book, Fraistat looks at “Ideas of Poetic Order and Ordering” and “Forms of Coherence in Romantic Poetic Volumes” in the “contexture” that results from the poets’ deliberate sequencing of poems in Romantic poetry collections, and he begins his discussion by noting that Blake’s Songs display “in its most unadulterated form . . . the Romantic urge not only to structure, but to restructure, contextures” (4).

However, Fraistat does not discuss the Songs at length, focusing instead on William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, John Keats’ Lamia (1820) collection, and Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound (1820) collection. For Fraistat, contexture describes the fabric of the book created by the weaving together of the “inner” meaning of a given poem taken separately and the “outer” meaning of the poem considered as part of an ordered sequence. Fraistat lists a number of possible contextural structures based on “subject, theme, image or voice,” noting that the use of titles, epigraphs, or prefaces can also suggest possible relationships or continuities among the poems in a collection (12). Fraistat’s point is that in the original publication, the poet placed the poems in each collection into a particular sequence, and the meaning and significance of a particular poem depends at least in part on its position in that original sequence with other poems.

Fraistat’s focus on the author’s intentional sequencing of the poems in a collection implies a tension between authorial and editorial concerns that I have explored in a class on anthologies (see the sample syllabus). On the one hand, editorial decisions may be seen as manifestations of certain theories of literary value that may have little to do with the author’s original decisions about organizing his or her book. Fraistat’s approach to authorial concerns, on the other hand, assumes that poets expected readers to read the poems in their poetry collections in the order in which they appear, and that in such a sequential reading, various relationships would emerge for readers. For Blake’s Songs, the authorial concerns reflected in Fraistat’s notion of contexture are rather more complicated than for many writers. In the case of the Songs, what constitutes the contexture? Certainly the sequence of poems in any individual copy provides the foundation for the contexture of that copy. Working with only the Blake Archive, we can now compare the contextures in thirteen different copies. Can we weave these separate contextures into a fluid multi-dimensional setting for each poem? Moreover, in some cases the poems in an extant copy were not sequenced by Blake but by a later owner, so the provenance of a particular copy may be included as part of its larger contexture. As such, these copies come to the reader already encrusted with the traces not only of interpretation but also the values assigned by the historical and commercial processes that led to the copy’s assembly. Finally, we must add Blake’s use of stereotypes of text and design to Fraistat’s list of “subject, theme, image or voice” as possible bases for contexture, opening up questions of visual as well as verbal relations. The object of our study looks less like a sequence of pages than a cluster of intersecting spheres that largely overlap but are nowhere identical.

I noted that I teach the full Songs in several different classes, but the truth is that I assign the full Songs in several different classes, without ever teaching all of the poems. There is just not enough time to do so. Instead, I try to use poems that give a sense of structure and theme, poems that suggest some point I want to make. I do feel a sense of responsibility to the collection’s critical history, so I make a point to discuss “The Lamb” and “The Tyger” for at least a bit, but the differences in purpose and focus of the various classes mean that I have to approach the Songs differently in each course. Nonetheless, I always try to use the Songs to allow students to explore the various possible lines of continuity as well as the more theoretical questions concerning the stability of the text. What sort of work allows for so many different manifestations? What sort of artist envisions such a work? How does Blake imagine his control over his creation? Even with half a semester devoted to the Songs, these are questions toward which I feel I only gesture.

But perhaps we can imagine a class I have never actually taught, but which I can begin to see on my horizon. It is a class exclusively on the Songs. With fifteen weeks (more or less) we can deepen our study considerably. Take a week each for the students to read through the Songs of Innocence and the Songs of Experience. Then use a week to introduce them to the Blake Archive and the different copies. Then, depending on class size, assign each student or team of students one particular copy of the Songs to adopt. Their task now is to be the expert on their copy. The course would include regular updates on what each student has learned about his or her copy. Discussions of individual poems would be informed by each student’s different textual and contextural experience, considering placement in a particular sequence as well as coloring, history, or provenance. The history of each book is part of the character of the individual copy and therefore part of the character of the full Songs, the ultimate composite text comprising all copies. In the classroom, this is about as close as we might get to experiencing the Songs for the slippery, protean book it actually is.

Toward a Blakean Pedagogy

The multiple sequences of the Songs demonstrate that Blake accepted a certain amount of play in what constituted a “finished” work as well as in his readers’ reactions to and reconstructions of that work. Teaching the multiplicity of the Songs requires teachers and students to embrace that play as well. Therein lies the key to a Blakean pedagogy. Perhaps Blake’s most famous statement on pedagogy is his remark to Dr. Trusler in a letter dated August 23, 1799: “The wisest of the Ancients considered what is not too Explicit as the fittest for Instruction because it rouzes the faculties to act” (Erdman 702).

Blake seems to assume that the typical state of mind is inactive and not conducive to learning; the mind is bound by its own “mind-forg’d manacles” (8) that the poet marks in every face he meets in “London.” The faculties must be roused, released from those manacles, in order to learn, and the “not too Explicit” makes that happen. But how?

The mental lethargy to which Blake responds is clearly evident in “The School Boy” which appears in both Innocence and Experience at different times. The schoolboy states that school, where “I drooping sit” (11), “drives all joy away” (7). The schoolmaster has a “cruel eye” (8), and the oppressive atmosphere is such that “Nor in my book can I take delight” (13). Ironically, school is where mental lethargy sets in; the process is equivalent to caging a bird (16-17), nipping fresh buds, or stripping “tender plants” (21-23). The effects of this stifled mentality are dire for they leave us unable to “gather what griefs destroy / Or bless the mellowing year, / When the blasts of winter appear” (28-30). Without a joyous, nurturing education, we are left unprepared in later life either to learn from our losses or to appreciate our blessings.

When the schoolboy laments that he cannot take delight in his book, the complaint itself suggests that however much he might like to enjoy his learning, the schoolmaster is preventing that by his methods of instruction. What does delight in learning mean to Blake? Blake’s comments to Trusler suggest that the mind responds to the challenge of the “not too Explicit” by rousing itself to the puzzle and presumably experiencing the joy and energy lost in the schoolboy’s classroom. Knowledge for Blake is discovery. It is the grasping of the lesson behind the not too explicit, and part of that lesson is an awareness and appreciation of the process of learning, of inquiry, of discovery. As Wordsworth puts it in the preface to Lyrical Ballads, it is the pleasure of “difficulty overcome” (611).

I often tell my students that Blake’s poems are like little linear accelerators, in which the atomic particles of the text crash into each other, throwing off clouds of possible meanings. I think this is true of all texts, but I think it is especially true for Blake. Those clouds of possible meaning require a certain faith in the interaction between reader and text, student and teacher. The lessons of the Songs are not the sort of knowledge that can simply be transferred from the author to the reader or from the teacher to the student. Rather, the lessons of the Songs depend on awakening the reader to multiple possibilities and points of view. Blake thought that most people sleepwalk passively through a book the way that they sleepwalk through their lives. They must be taught to read in the infernal method. Skepticism is a requirement, as are independence of spirit and a willingness to question the received interpretations of past authorities. Blake intends his books to force the reader to wake up, to “rouze” the mind to act. A Blakean pedagogy requires a negotiation between control and freedom. In Jerusalem (comp. ca. 1804-1820), Los says to “Labour well the Minute Particulars” (55:51), but the point of such labor is to release possible readings, to make visible the infernal readings that are hidden by the encrustations of tradition or the “mind-forg’d manacles” of expectation or prejudice or idolatry. Blake knew—and the teacher of Blake’s works must accept—that he had only very limited control over what the reader made of his books, but he knew that we must begin with the material object—the book itself—and build up from there. In his stereotypes—the composite of text and image—Blake tried to retain as much creative control as possible, choosing his own handwriting over standard print, his own integrated images over the standard publication layout. In building the contextures of the individual copies, we also build a contexture of the interaction of those copies with each other. Some of those copies have been sequenced by Blake, others were sequenced by collectors or booksellers; either way, those copies and their special circumstances are part of the contexture of the overall Songs of Innocence and of Experience.

In that MLA collection on teaching the Songs, Stephen Cox discusses “Taking Risks in Teaching Songs,” but the risks in 1989 are different from risks twenty-five years later. For Cox, risk constitutes using discussion classes to teach students critical thinking about the content and value of the Songs, and the evidence we use to establish either. Literary theory and classroom practice have changed much since then, and what Cox finds risky, I think is probably close to standard practice today. We might push these methods further, especially with the resources now available, but in the end, we may find that simply reading poems honestly with our students is all that we need to do. If we expect our students to embrace the play and uncertainty of Blake’s work, we as teachers must ourselves be open to such play. I know that, regardless of which particular poems I may prepare for classroom discussion of the Songs, I rarely end up discussing those poems. My class preparation is more of a back-up plan in case the students do not have any questions or preferences among the poems; it’s good to be prepared, but I rarely use it. Instead, I ask the students what questions they have or what poems they especially liked or which ones might have confused them. Their answers usually lead away from the poems that I had prepared, and those are usually my most productive classes. Obviously I’ve read all of the Songs more times than I can count, but I rarely have a reading of a particular poem at my fingertips. Consequently these classes are exploratory and almost purely improvisational, as discussion inevitably leads to unexpected approaches, questions that I had not considered, or a level of detail that I don’t often examine. And this is good because most students have never experienced reading a poem with someone who knows what she’s doing and who is willing to share with the class the mistakes, the false starts, and methods of approaching the problem.

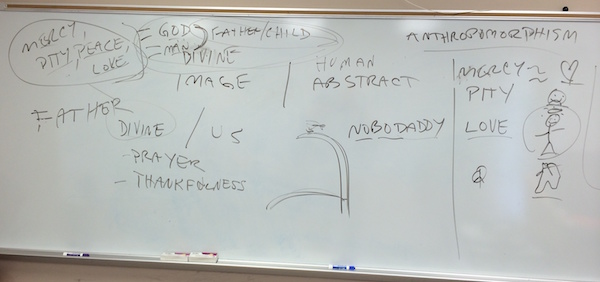

I recently had such a discussion of “The Divine Image” that shocked my students by consuming the entire 75-minute period. The whiteboard from that discussion is here:

Fig. 1 Whiteboard for “The Divine Image.”

I do a lot of board work in these more exploratory sessions. I put key terms and ideas up, grouping them, drawing in connections. Stick figures and badly-drawn maps are functions of my classroom persona, and I use them to help visualize and organize the concepts. For this class I had prepared to discuss “Infant Joy” and “Infant Sorrow,” but a student asked about “A Divine Image,” so we went there instead, and that quickly led to investigation of “The Divine Image” as well. With no prep, I was feeling my way along, stanza by stanza, and the board notes suggest the dynamic of exploratory thinking. We simply looked at what “The Divine Image” says. If we pray to and return thanks to the traits of “Mercy Pity Peace and Love” (1), that would seem to identify God with those traits. The second stanza confirms that conclusion but extends the reference to “Man” (8) as well as “God” (6), while also introducing a parental relationship between God and Man. All of this is represented on the left side of the white board. The image in the middle represents the design of “The Blossom” which is similar to the design for “The Divine Image.” The words and images at the right depict the associations made in the third stanza of “The Divine Image” and emphasize the anthropomorphism of Blake’s concept of the divine. All of this was generated by the class discussion. The students came away with a clearer sense of what the poem is about as well as a heightened awareness of the process of discovery.

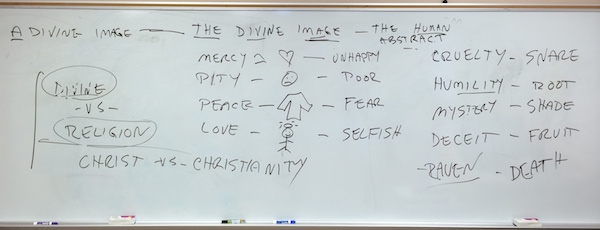

Since the discussion of “The Divine Image” had been triggered by a student’s question about “A Divine Image” (the unused companion poem), in the following class we looked at how “The Divine Image” relates to both “A Divine Image” and “The Human Abstract,” the poem that Blake used instead. We noted how the fragmenting of the body and the negative attributes of “A Divine Image” mirror the fragmentation and positive attributes of “The Divine Image,” while also recalling the industrial imagery of the blacksmith from “The Tyger.” Then we considered “The Human Abstract” and the variations it plays on both the positive attributes of “The Divine Image” and the negative attributes of “A Divine Image” in a narrative that recalls both the biblical story of the Fall and “A Poison Tree.” Here is the whiteboard for that discussion:

Fig. 2 Whiteboard for “A Divine Image.”

The second board suggests a more orderly approach on my part on the second day as we set in place the alternative associations established in “The Human Abstract.” I learned a lot in these discussions. Part of the discussion was about the poems and how Blake represents the relationship between the human and the divine. But we also learned that sometimes the Blakean ideas or images that seem most strange actually make the most sense if taken at face value. I find that most new readers of Blake understand what he says; they just can’t believe he said it. I counsel my students that confusion is an appropriate first response to much of Blake’s work. All three poems we discussed create chains of associations with the divine attributes of Mercy, Pity, Peace and Love. The fragmenting of the body, its industrialization in “A Divine Image,” the cryptic allegory of “The Human Abstract,” and the conflicting associations all make the poems’ statements seem strange. Nonetheless, the associations are quite clear if we just record what the poems say.

The whiteboards from class show a movement from exploration to understanding. A Blakean pedagogy demands that teachers and students alike approach the poems with an open mind and a sense of adventure. This is reading in the infernal method: confronting the essential strangeness of poetic pronouncements intruding into the mundane world and accepting that strangeness as an invitation to play, to learn, to rouse the faculties. Blake’s designs are filled with images of people reading. Some cover their books so no one else can see, but more often, Blake shows adults and children reading together. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790), the poet and his new friend, an “Angel, who is now become a Devil,” “often read the Bible together in its infernal . . . sense” (Plate 24). Discussion and skepticism must be the basis for any Blakean pedagogy. But for anyone who knows Blake’s work, this seems hardly to need saying.

Probably in 1818 Blake sent to Thomas Butts (probably) a list identifying “The Order in which the Songs of Innocence & of Experience out [sic] to be paged & placed” (Erdman 772). The nature of Blake’s response suggests that Butts had asked him about the correct order of the poems, a question he would only ask if he knew that there were copies of the Songs with different sequences. Butts does not go as far as John Linnell did with Copy F of Jerusalem (1827), actually changing Blake’s page numbers to match the pagination in his own copy, but his question suggests the same sort of desire for a stable text that we often find in our students.

Nonetheless, everything about the Songs works against the fulfillment of that desire, and I must admit to a certain satisfaction in the fact that only Copy V (1821) exhibits the correct “Order” outlined in the letter to Butts; not even Blake’s own copy follows the sequence. I teach the Songs especially to my new English majors precisely because I want them to think about what makes a book, and whether a book is ever a stable authoritative statement. I use Blake to make certain points about the nature of literature, the nature of reading, the nature of reality. The lesson of the multiplicity of the Songs is to embrace the uncertainty of new relationships and to discover the possibilities that arise from the combination and recombination of words and pictures, poems and books.