Mary Wollstonecraft’s second published work, Original Stories from Real Life; with Conversations, Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness (1788), was her first commercial literary success, running into six editions over twelve years and establishing her reputation as an authority on both childhood education and literature for children. However, despite its contemporary success, Original Stories

has fallen off the radar of recent critical explorations of romantic-era children’s literature and of romantic views of childhood, perhaps mentioned in passing or relegated to a footnote while whole chapters are devoted to the works of Maria Edgeworth, William Wordsworth, Hannah More, or Sarah Trimmer. It is frequently dismissed as an anomalous example of a radical writer producing apparently conservative and apolitical work for children (see: Mary V. Jackson and Geoffrey Summerfield, among others

) or as a mere illustration within discussions of radical writers for adults who “also” wrote for children. The role that Wollstonecraft’s works for children played in the veritable explosion of literature for children in the last two decades of the eighteenth century has yet to be explored fully.

However, no attention whatsoever has yet been focused on Original Stories’ own generic hybridity and the implications that such hybridity has both on the way we read the Stories themselves and on the ways in which we can place that work within Wollstonecraft’s body of work and amongst the parallel productions of her contemporaries. Original Stories is a unique amalgam that owes a part of its makeup to the popular moral tales for children (from the works produced by John Newbery earlier in the century through the newer productions of writers like Trimmer and Anna Barbauld) but also draws on elements of romance (as we shall see, a controversial subject for children’s reading) and the so-called “romance of real life,” a genre identified by Michael Gamer and popularized in part by Wollstonecraft’s contemporaries Charlotte Smith and Maria Edgeworth. Even the most cursory glance at Wollstonecraft’s work’s title hints at its generic heterogeneity. “Original stories” suggests an imaginative source, while the phrase “from real life” seems to make the paradoxical claim that the stories are both empirically true and verifiable while at the same time “original” creations. The next portion of the title informs us that these “stories” contain “conversations,” again implying a quasi-journalistic truth claim, while “calculated,” “regulated,” and “form” all suggest that this is a book with a premeditated mission and pedagogical purpose. Finally “affections,” “mind,” “truth,” and “goodness” all present the qualities and entities that Wollstonecraft’s project aims either to instill or improve and are themes she will return to in later works, including the attempt in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman to carve out a space for the rational female mind capable of housing both “affections” and reason.

Original Stories is not Wollstonecraft’s only work that presents a vexed relationship between different genres, and specifically between the antipodal pulls of realism and romanticism, rationality and imagination: note for example the generic funambulism in Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman (1798) between romance’s impossibly dramatic characters (represented by the gothic sufferer Maria and her improbable prison romance) and passages of stark realism (as in Jemima’s chillingly realistic narratives of society’s underbelly). Wollstonecraft’s published works encompass the genres of “thoughts,” a “view,” and “letters,” and the self-presentations of the two Vindications as explorations of the realities of contemporary society are offset by the sense of novelistic un-reality proclaimed by the title of the pseudo-autobiographical Mary: a Fiction (1788); clearly Wollstonecraft was no stranger to generic experimentation. But her participation in the genre of “tales” or “romances of real life” (itself a generic hybrid) in her only original work aimed at children suggests a particular set of ideological assumptions regarding the didactic and pedagogic values of realism. The fact that this questioning of genres was of particular interest to the period’s women writers, coupled with the fact that, as Mitzi Meyers demonstrates, women were not only the principal producers of literature for children, but also among the leading educational theorists of the day, suggests that an exploration of precisely what Wollstonecraft intended with her “original,” instructive stories “from real life” aimed at children might help clarify not only Wollstonecraft’s own literary and philosophical projects but also the growing genre in which her Original Stories participates. When we consider that Charlotte Smith’s The Romance of Real Life was published in 1787, at the time Wollstonecraft was writing her Original Stories, and that Wollstonecraft was familiar with Smith’s work due to the former’s position as a reviewer for The Analytical Review,

the lines of association between Original Stories and the romance of real life genre become clearer. Reading Wollstonecraft’s collection of stories “from real life” as simultaneously a comment on, expansion of, and conversation with Smith’s recent collection of stories “of real life” will help illuminate the generic experimentation of each.

The identification of the romance of real life as not only a genre distinct from the novel but as a sort of anti-novel in which the excesses of romance are “corrected” by an attempted synthesis with history (that most dignified of discourses) suggests the period’s unease regarding the novel’s status and respectability, especially when it is produced or consumed by women (Gamer, “Romance” 237). The shifting role of women as both writers and readers of novels and the dangers of women’s allegedly innate sensibility are subjects to which Wollstonecraft turns her attention in the second Vindication and in its claims that the “exquisite sensibility” that women are encouraged to cultivate and the novels they are taught to swoon over relegate them to a “state of perpetual childhood” (9). Women authors of the 1780s had to contend not only with the usual questions of respectability that troubled any professional woman writer but also with the perception that the novel was a genre particularly dangerously suited to women’s acute sensibility. This conflict between women writers’ attraction to the novel as a new and accessible discourse (for it required no formal training or knowledge of classical languages) and the sense that, despite the earlier success of Frances Burney and Sarah Fielding, women’s suitability to the genre was questionable, inspired the experimentation with a new genre that merged the entertainment value of the romance or novel with the respectable and edifying genre of history.

Another motivation for women to present their writing as something with direct ties to historical fact is related to Myers’s claims that the popularity of both moral tales and children’s literature with women writers was an attempt to appropriate the realm of education as a domestic (and thus feminine) concern and, concurrently, to gain recognition in the world of letters that was in the 1780s and early 1790s still very much a masculine realm. Insisting that the tales they tell— even the apparently “romantic” ones—are drawn from real life imparts to women writers a certain palpable authority and prevents them from becoming mere “novelists.”

If we recognize the proliferation of so-called realistic romances among early romantic women writers as a defensive fusion of romance with private memoirs, domestic biographies, and other allegedly ahistorical discourses in an attempt to attain the authority of truth, we are invited to read any such self-proclaimed real-life tales as an attempt at self-ratification. For example, although Wollstonecraft’s Stories do not label themselves as “romances” per se, her title’s emphasis on both originality and realistic mimesis suggest this same sort of self-conscious acknowledgement of the apparent difficulties of the female writer to duplicate faithfully the world around her.

Smith’s preface to The Romance of Real Life provides as clear and revealing a summary as one could seek of these tensions surrounding one writer’s forays into the seemingly incompatible genres of romance and history. In Smith’s case, she finds both genres lacking for her purpose and instead constructs a hybrid discourse that borrows aspects from each genre and is simultaneously both and neither: ‘A Literary friend, whose opinion I greatly value, suggested to me the possibility of producing a few little volumes, that might prove as attractive as the most romantic fiction, and yet convey all the solid instruction of genuine history. He affirmed, that the voluminous and ill-written work, entitled Les Causes Célébres, might furnish me with very ample materials for so desirable a purpose. He advised me to select such stories from this collection, as, though disfigured by the affectation and bad taste of the compiler, Guyot [sic] de Pitaval, might lead us to form awful ideas of the force and danger of the human passions. He wished me to consider myself as under no restriction, but that of adhering to authenticated facts; and by telling each story in my own way, to render it as much as possible an interesting lesson of morality. (129

)’ Perhaps the first thing that strikes the reader is the female writer’s reliance on the unnamed, male, “Literary friend” (identified by Gamer as William Hayley; 298) whose guidance she seems to solicit or even require. It is this friend who proposes the project, suggests the source text, and advised the author how and in what style she ought to proceed (three of the paragraph’s four sentences begin with the male friend’s proclamations: “He affirmed […] He advised […] He wished”). Such apparent deference on the part of a fledgling female writer (who had produced only one other prose work, a translation of Prèvost’s Manon Lescaut, in the previous year) might be understandable if not for the fact that, although new to prose, Smith was already a well-established literary figure by 1787. Elegiac Sonnets

had been an immediate commercial and critical success when it was released in 1784 and by 1787 was already in its fourth English edition, meaning that Smith was by no means a novice to the book trade. So why, one might wonder, does this capable and successful author seem to defer to a male preceptor? Her translator’s preface to Manon Lescaut, in contrast, is authoritative with its claims that she herself found the original novel in Normandy and amused some English friends by masterfully translating passages extempore. She also proudly declares the liberties she has taken with the text, including lengthening the short sentences she finds “so unpleasant to the English ear,” altering the narrative structure, and eliding many “trite” and repetitive passages (5), claims which all suggest an author in command of her source material and comfortable with her authority. However, Manon Lescaut was published anonymously—its title page simply proclaiming itself “A French Story”—and the preface contains no tell-tale pronouns or details; indeed, the public seems to have assumed that the translator was male (Fletcher 84). The fact that The Romance of Real Life was Smith’s first work in prose to feature her name on the title page might have contributed to the fact that the beginning of its preface seems to defer to masculine literary authority.

However, this apparent obsequiousness is more complicated than it first appears, and as the preface progresses this sense of deference falls away and is replaced by the same confident, authoritative tone that characterizes Smith’s earlier, anonymous preface. The “Literary friend” is never again mentioned, and Smith is openly critical not only of the original (male) author, Gayot de Pitaval (claiming that “the style of the original is frequently obscure; the facts are often anticipated, and often repeated, in almost the same words, in different parts of the story,” among many other complaints) but also of a new edition of the same work by François Richer, claiming that his work is “less interesting” and less accurate than her own. Her announcement that Richer has produced another, inferior French version of “my original” (emphasis added) suggests the degree to which she saw herself as “owning” the text she had completely rewritten. The “great pleasure” she has taken in the work, despite its many complexities and roadblocks, is repeatedly emphasized. Even as the difficulties of her task had begun to overwhelm her, she claims, she kept in sight the potential usefulness of her project, and it is this mission that made the experience pleasurable: ‘Yet it occurred to me, that the reason which made the work difficult and unpleasant for me to write, would render it, when finished, a desirable book to those who may wish to obtain some idea of a celebrated publication, without wading thro’ the obscurities and extraneous matter of M. de Pitaval. (129) ’ This is a pivotal (forgive the pun) moment in the preface, a moment in which the author emerges from the passive figure that occupied the first paragraph, and an emergence that centers not only on her rejection of the authoritative original she is adapting but also on her ambition that the book have instructional value. While the author’s reliance on her male friend might be the first noteworthy feature of the preface, it is by no means its only one; in fact, when read in light of the remainder of the preface, the first paragraph’s agenda becomes clearer and, I would argue, considerably less straightforward than it first appeared. Although the spectre of the Literary friend’s influence hovers throughout the opening paragraph, the claims that Smith herself is making for both her own agency and for her project’s pedagogical purpose begin to surface with her statement that “by telling each story in [her] own way, [she will] render it as much as possible an interesting lesson of morality.” This discovery of her “own way” in which to remake these frivolous French tales signals her intention of making these stories “both interesting and instructive,” unlike “romantic fiction” (which is “attractive,” but, it is implied, not instructive) and “genuine history” (which contains “solid instruction,” but less attraction). Since neither mode of discourse is entirely satisfactory, she will make her own by “adhering to authenticated facts” while at the same time “telling each story in [her] own way.” This hybrid that she has created—part attractive romantic fiction, part “genuine history”—is presented as an improvement not only over the forty-year old original that was “disfigured by the affectation and bad taste” of its creator (or was, in other words, factually accurate but stylistically flawed), but also the new version by Richer unmixed with romance and therefore “less interesting.” Smith is not claiming that romance and history are mutually exclusive, rather that neither side tells the entire story, or tells the story in a way that makes it attractive and, therefore, useful as a moral instructor. This is the impetus behind her unique title that was to launch a thousand spin-offs, for “the romance of real life” is nowhere close to a faithful translation of the original French title, Les Causes Célébres. Smith is clearly not aiming for an accurate translation of the title, but rather a transformation of it, whereby the two elements that she sees as necessary for a literary work’s instructive value—that the tales be true (because nothing is as educational as experiencing the “real”), but are told as if they were fiction (because nothing is as satisfying as a good read)—combine to form a palatable mixture of fiction and reality. If a work is (or even claims to be) drawn from real life, the lessons that can be gleaned from it are almost as valuable as actually having the same real-life experience. Readers at home can live through the harrowing adventures of Anglade or Louisa d’Antail, and, through the virtue of a sensibility that would relate their feelings of empathy to real people who actually existed, they might feel deeply for them and learn from the sufferers’ examples as if they were their own experiences. Smith’s brief and modest-seeming preface is in fact a watershed moment for the generic conventions of prose. It is the introduction of realism into romance, of history into fiction, and its central claim that this hybridity is necessary in order to produce a work of prose “both interesting and instructive” (and the implied claim that this is what good prose should aim to do) signal a new way of thinking about the purpose of writing.

It is perhaps no coincidence that Smith—herself a mother—comes to this revelation at the same time that the English public is becoming obsessed with the child reader. Due in part to the new availability of cheap paper, a subsequent upsurge in publishing activity, and increased literacy rates among all classes, the last decades of the eighteenth century saw an unprecedented interest in producing printed material aimed at children, material that often came loaded with ideology. From Hannah More’s Cheap Repository Tracts that preached duty, obedience, and conformity to prevalent social values to the piously conservative works of Sarah Trimmer, the new literature available to children was obsessed with what sorts of lessons children might glean from the written word. Too much romance or fancy, even in the form of chapbook fairy tales, was seen as dangerous to young unformed minds in a way that should remind us of the period’s anxiety about the effect fiction might have on the similarly immature minds of women (as in Wollstonecraft’s claim that women are being relegated to a “state of perpetual childhood”). Imagination was a dangerous quality to cultivate, since it taught children to imagine worlds other than the one in which they were born into—a world in which, for example, Little Goody Two-Shoes can rise from poverty through schooling, become a governess, and marry a rich nobleman—and introduced them to the notion of choice, the idea that their destinies were in their hands and that any ragged child could, through hard work, virtue, and a bit of luck, become a prince or princess. Thus in class-bound England, especially in the years after the French Revolution, imagination suggested radical democratic ideals and leveling—dangerous concepts in a society in which literacy rates were rising in the lower classes and Paine’s Rights of Man (1791) was a runaway best-seller. In 1802 Trimmer founded the Guardian of Education, a version of the Anti-Jacobin Review specifically aimed at rooting out subversive elements in children’s literature. The world of romance and imagination was seen by many as singularly unfit for childish consumption (just as too much novel-reading would corrupt their silly mothers), and books for children were thought to require a strong moral stance and firm basis in real life, where animals do not talk and poor little girls never become fine ladies.

However, as Smith notes in the preface discussed above, “solid instruction” itself is not sufficient to retain the interest of any reader, young or old, without some of the attraction of “romantic fiction.” It is this happy medium that Wollstonecraft tries to deliver with her Original Stories from Real Life, an attempt to synthesize the moral instruction that many, including Wollstonecraft, felt that children need while also providing them with the elements of fiction and story-telling that they desire. Although a lack of definitive proof in the form of reviews or letters makes it impossible to prove that Wollstonecraft read Smith’s Romance of Real Life in the year in which she was composing Original Stories, the complementary titles alone would suggest that, even if no direct influence exists, the two writers were at least drawing from the same ideological pool. Regardless, it is highly likely that Wollstonecraft did indeed read Smith’s work in 1787; in that year Wollstonecraft left her position as a governess in Ireland and headed to London, where she became a member of Joseph Johnson’s circle and immersed herself in literary life, and due to her position with The Analytical Review she had already reviewed Smith’s work as early as July 1788. Even without a definite provenance, however, it is clear that both Smith and Wollstonecraft had in mind similar reexaminations of the generic conventions of prose and ideas regarding the pedagogical import of realism. Their audiences might have differed—Wollstonecraft’s consisting of children (and their parents) in need of moral instruction, and Smith’s the wider reading public—but their motivations and techniques are surprisingly similar. In fact if we bracket the central frame of Original Stories—Mrs. Mason’s storytelling and careful manipulation of situations that allow her charges to experience the stories of others—its similarities to Smith’s Romance become striking: both works feature a collection of disjointed tales that illustrate well-defined morals and are presented as historically and factually true accounts of real experiences colored with an imaginative cast.

Wollstonecraft’s preface immediately delineates the text’s purpose and testifies to its necessity: ‘These conversations and tales are accommodated to the present state of society; which obliges the author to attempt to cure those faults by reason, which ought never to have taken root in the infant mind. Good habits, imperceptibly fixed, are far preferable to the precepts of reason; but, as this task requires more judgment than generally falls to the lot of parents, substitutes may be sought for, and medicines given, when regimen would have answered the purpose much better. (359)

’ Wollstonecraft clearly presents hers as a modern project, addressed to “the present state of society” and necessary to combat the insidious forces implanting themselves, weed-like, into the “infant minds” of the next generation. In a later paragraph Wollstonecraft essentially dismisses contemporary parents, noting that they have their “own passions to combat with, and fastidious pleasures to pursue” and are therefore too busy to tend to their children’s moral education themselves; she proposes that we address our efforts to salvaging the succeeding generation, which might yet be taught the virtue their parents lack.

The picture she paints of frivolous, inattentive parents—and for “parents” we can safely read “mothers”—is one to which she will return in the second Vindication and its claims that women schooled in sensibility and manners but lacking common sense, practical training, or any knowledge beyond the parlor or nursery leads to a weakened society.

The fourth paragraph of the preface even claims that the text—written in a mature style which, she acknowledges, might be “not quite on a level with the capacity of a child”—might be as useful to the adult who would read it aloud to the child as to that child itself: “The Conversations are intended to assist the teacher as well as the pupil.” This statement—along with the fact that, indeed, the style is hardly childish, and many of the situations mature—suggests that Wollstonecraft’s intended audience might be wider than it first appears; a second glance at the full title discovers that children are nowhere mentioned, and it is not “childish minds” but “the mind” that the title claims to “form.” The fact that the text was published by J. Johnson, a house not yet known in 1788 for its juvenile productions, would have contributed to the impression that this was a text for all, offering instruction not only to children but to their parents as well.

The method Wollstonecraft chooses to promote reason to the next generation takes a form similar to that which we have seen previously. She has already in the preface’s opening sentence claimed that the work to follow will be comprised of “conversations and tales” and notes in its final sentence that “the Tales which were written to illustrate the moral, may recall it, when the mind has gained sufficient strength to discuss the argument from which it was deduced” (360)—in other words, the tales are the instruments with which an attentive reader might arrive at the real-life lesson, much as Smith’s “attractive” fictional style was the means of delivering her real-life lessons. Wollstonecraft’s preface makes another similar claim: ‘The way to render instruction most useful cannot always be adopted; knowledge should be gradually imparted, and flow more from example than teaching: example directly addresses the senses, the first inlets to the heart; and the improvement of those instruments of the understanding is the object education should have constantly in view, and over which we have most power. (359) ’ This idea that unadulterated “instruction” is not always the best method of teaching, that sometimes “examples” that address the “senses” and “heart” are more effective vehicles of education and refinement, echoes Smith’s claims for the insufficiency of “solid instruction” alone. Elsewhere in her preface Wollstonecraft notes that the “affections”—highlighted in the work’s subtitle—are the forces that should “warm the heart, and animate the conduct,” suggesting the same interest that Smith demonstrates in the sensory processing of literature. Again, the reader is presented as engaging in the same sort of relationship with the text whereby the experiences he or she reads about will affect their sensibilities in the same way as would actual lived or directly observed experiences. The idea that reading these stories—or having them read out loud—will do as much good for any child as they did for Mary and Caroline is ratified by Original Stories’ last chapter, in which Mrs Mason presents her charges with a book—presumably the book, Original Stories itself—recording all of their adventures and conversations and claims that it will act as a substitute for their real-life guide; she then asks that the girls write to her, but only if they record “the genuine sentiments of [their] hearts,” which suggests confidence that that such things can truly be duplicated in a letter. The belief that the written word can faithfully replicate the truest expressions of heart and mind is perhaps not a new one, but what is new here is the concept that this direct line between heart and pen can serve a useful purpose, that sensibility might be put into the service of morality.

The structure of Original Stories demonstrates this concept. Having observed a moral shortcoming in one or both of her charges, Mrs Mason orchestrates a scenario in which she can offer a counter-example; for instance, after seeing the girls kill insects, Mrs Mason makes an elaborate show of walking off the path and into the wet grass to avoid stepping on a line of snails. After offering a brief homily on the topic, she then tells a series of short accounts of other people’s experiences in similar situations, often using only vague descriptions and no proper names; on the issue of cruelty to animals, anonymous accounts of puppy-drowning and guinea-pig-torture ensue. Up until this point, the Stories’ pedagogical project is fairly straightforward: the girls are told that what they are doing is wrong, and they are offered examples of how other people erred in the same way in order to shame them into a different behavior. It is the final step in Mrs Mason’s program of moral education that supports the claims Wollstonecraft makes in the preface regarding the necessity of knowledge that flows from example and hinges on sensibility and affection: the girls are plunged into the actual and are taken to view real relics or meet real people whose true stories ratify their tutor’s tales. Standing before crazy Robin’s cave, Mrs Mason relates the story of the man she actually knew, assisted, and even wept with over the body of his murdered dog, serving as an eyewitness to the events she describes. This “real life” example is shown as making an immediate impression on the girls: “Was that the cave? asked Mary. They ran to it. Poor Robin! Did you ever hear of any thing so cruel!” (376). Mrs Mason’s presentation of the actual Robin’s cave produces a reaction in Mary and Caroline far more marked than any of her stories and examples ever had, demonstrating the pedagogical value of the real. Not coincidently, this move from story into reality is also the point in each “real life” example that elements of romance and sensibility are the most marked. The account of Robin standing over the bed containing his dead children is a scene ripped straight from the pages of a sentimental novel and engineered to elicit its audience’s tears: ‘The poor father, who was now bereft of all his children, hung over their bed in speechless anguish; not a groan or a tear escaped from him, whilst he stood, two or three hours, in the same attitude, looking at the dead bodies of his little darlings. (375)’ In these examples, pathos is key, demonstrating Wollstonecraft’s theory that sentiment can inspire genuine moral reformation, both in Mary and Caroline and in the readers of Original Stories (for these are also presented to the readers as tales “from Real Life,” just as the introduction presents Mary and Caroline as real little girls with a true history). The rest of the collection continues in much the same vein: a failing in the girls is identified, a lecture laced with religious instruction is given, a “real life” story is told, and some sort of proof, often in the form of the person himself or herself, is produced. Throughout Original Stories, the real person, place, or experience is consistently portrayed as a force that supports the stories people tell. As in Smith’s conception of the romance of real life, historical fact and storytelling are complementary, rather than contradictory, concepts. Whenever Mrs Mason tells a character’s history, real-life details ratify her version, and when those stories are told, they are told in a manner that borrows conventions of romance and sensibility to make the tale even more affecting, sympathetic, and thus instructive.

One aspect of Wollstonecraft’s work less present in Smith’s is the recurrent preoccupation with religious duty and salvation, a characteristic that has erroneously led many critics to align Wollstonecraft with the many religious writers for children, including the aforementioned More and Trimmer, with whom Wollstonecraft had nothing else in common (and quite a bit at odds). The fact that the lessons Mrs Mason attempts to instill in Mary and Caroline are so often related to questions of Christian virtue suggests another layer of meaning to Wollstonecraft’s pedagogical aims. The idea that a book can be a vehicle for the dissemination of life lessons of course suggests the Protestant belief in the value of individual bible study, and Mrs Mason’s presentation to the girls of a book full of stories meant to “[illustrate] the instruction it contains” is clearly reminiscent of the New Testament. In fact, Mrs Mason herself is frequently and insistently portrayed as a Christ figure whose stories redeem the fallen girls, who are certainly no angels in the opening chapters. Even the “contents” page, with its list of chapter titles like “The Inconveniences of immoderate Indulgence” and “The Danger of Delay” suggests a collection of sermons or biblical parables. Mrs Mason repeatedly stresses that the way to do the most good in the world is by imitating God:

The greatest pleasure life affords [is] that of resembling God, by doing good. (368)You ought, by doing good, to imitate Him. (370)I now daily contemplate His wonderful goodness; and, though at an awful distance, try to imitate Him. (423)We are His children when we try to resemble Him. (431)

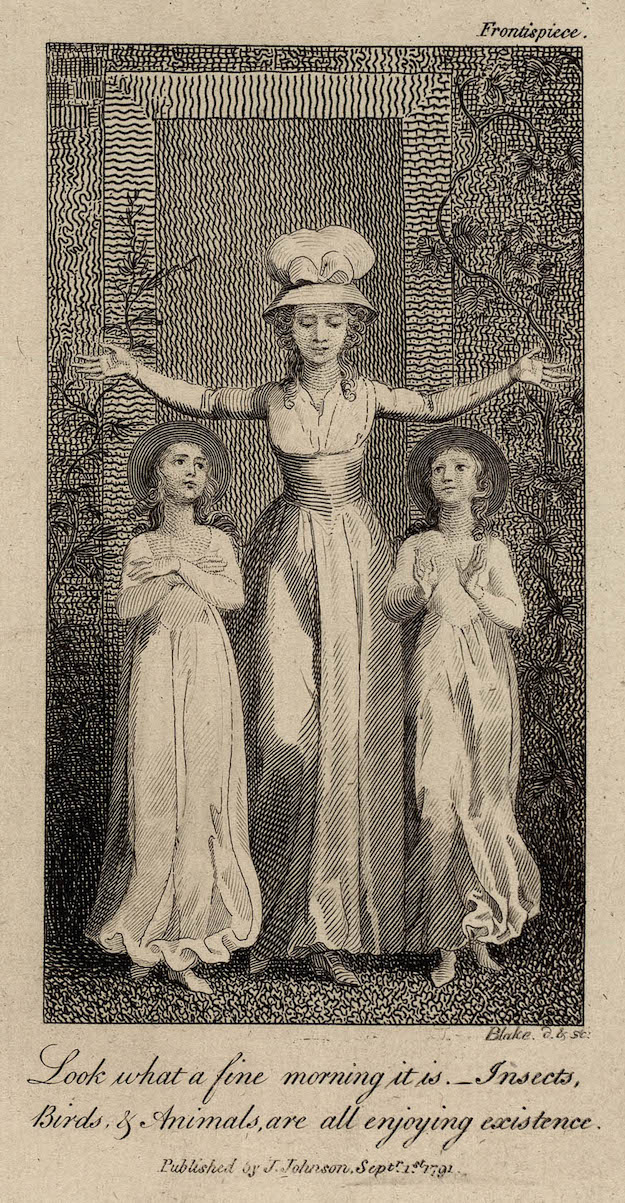

William Blake clearly picks up on Mrs Mason’s messianic fervor when he illustrates her in the frontispiece of the third edition with her arms spreading over the heads of her young charges, simultaneously a mother hen sheltering her brood and a Christ figure framed in a cross-like doorway, vines piercing her outstretched palms (fig. 1). While the preface claims that children’s introduction to true religion must come from a recognition of the “Universal Father” whom they will then wish to imitate, we see the girls awed by the all-seeing eye of their guardian and expressing a desire to imitate not God, but Mrs Mason herself, the text’s divine substitute—“I wish to be a woman, said Mary, and to be like Mrs Mason” (389). The idea that the real life of earthly existence is but preparation for a heavenly home—that the “Most High is educating us for eternity” (437)—lends an added urgency to the text’s stated goal to “form the mind to truth and goodness.” Patricia Demers claims that Evangelical writers like Wollstonecraft’s near-contemporary Mary Martha Butt Sherwood—one of a group Demers dubs “Romantic Evangelicals”—adopt a method of “seeing into the life of things, without contradiction or irony” which is “simultaneously domestic and eschatological” (131).

Fig. 1 William Blake’s illustration for Original Stories. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons).

As a result, ‘Their characters’ zeal in finding and defining an earthly home prompts their almost automatic longing for a heavenly home. Theirs is a consciously double vision, glimpsing the eternal in the natural, the sublime in the quotidian. (131)’ This “glimpsing the eternal in the natural” is one of the activities that Wollstonecraft repeatedly portrays Mrs Mason doing, and the idea that the text prepares one for real life, which then in turn prepares one for eternal life, is one that the character often trumpets. While there are some problems with aligning Wollstonecraft too closely to a group of writers with which she has little in common, the implication that Christianity yields a way of looking at real life as a heavenly preamble is important to bear in mind when considering Original Stories, a book which repeatedly presents itself as being concerned with Christian morality. The idea that real life is an important pedagogical tool because its lessons help us not only to become better citizens but also fit “to be angels hereafter,” with “a nobler employment in our Father’s kingdom” (371-2) and that Mrs Mason’s real-life tales and illustrations help Mary and Caroline not only to become better girls, but to become Christians and, eventually, angels is quite a burden to attach to any one text.

It is this idea of the “sublime in the quotidian” and the potentially salvific powers of woman on which I would like to end by tying together the various strains of ideology surrounding the blending of the genres of “real life” and “romance,” “factual” and “imaginary,” that we have seen occurring in Smith’s and Wollstonecraft’s texts. Even putting aside her many Christological qualities, Mrs Mason is an extraordinary female character to emerge from the 1780s: an independent landlord, munificent mistress, beloved pillar of her community, and unwavering moral guide. Her strict yet maternal presence portrays her as inhabiting what were in Wollstonecraft’s time two seemingly disparate spheres: the mother/woman, and the serious moral agent. Myers argues that, in fact, Wollstonecraft and her generation of writers for children (which would include Smith, who published Rural Walks only seven years after the publication of Original Stories) introduced the idea of “everyday female heroism” and the notion of the “heroic potential available in ordinary female life” (34; 50). Traditionally relegated to home and garden, women writers found new sources of inspiration, and their production of literature for children that reflected those sources spread them to the next generation. From the sense of anxiety regarding women’s ability to address historical fact and real life in serious literature sprang a hybrid genre that allowed them not only to temper history with the attractiveness of romance but also to elevate mere “romantic fiction” by infusing it with realism, turning it into something that can address history, society, and all aspects of “real life,” and, due in part to a changing cultural climate that put women in the position of educators, act as a pedagogical tool. There is a clear correlation between this experimentation with realism in the last decades of the eighteenth century and the development of the national tale in the early nineteenth, another hybrid genre that mixes romance and history, pioneered by women writers like Sydney Owenson (The Wild Irish Girl: A National Tale; 1806) and Jane Porter (The Scottish Chiefs; 1809). By the time Sir Walter Scott “invented” the historical novel with Waverly in 1814, he could draw on a rich tradition of texts in which the romantic and the realistic coalesced, a combination that has at its core the generic experimentations of women like Smith and Wollstonecraft.