Introduction: Setting the Stage

Romantic-period literature frequently asserts individual selves against traditional subjectivities. Various characters, including unacknowledged poetic geniuses, orphans, Byronic misanthropes, humanized gods, godlike everymen, and tragic last men have collectively contributed to the individualistic stereotypes at the heart of the ideal and ideological notions of Romanticism that have followed us into the twenty-first century. This literary litany of self-reflexive lyrics, esoteric compositions, and fictional caricatures associate independence with individualism in ways that eclipse the presence of collaborative, collective and creative interdependence during the Romantic era. Moreso than lonely creative voices, collective movements towards new subjectivities and subjective categorizations, driven by a dissenting, interdependent spirit of independence, permeated the revolutionary politics and inventive, collaborative aesthetics of this period in British history. Samuel Taylor Coleridge recognized this in “The Nightingale” (1798), which deconstructs the impossible-to-sustain idea of loneliness, independence and solitude among a community of warbling poets: “But never elsewhere in one place I knew / So many Nightingales: and far and near / In wood and thicket over the wide grove / They answer and provoke each other’s songs” (55-58).

This fundamental tension between collectivist and individualist pursuits of independence and the implicit acknowledgement of the necessity and inevitability of larger-scale interdependencies and collaborations is an essential characteristic of the period that needs to be more emphatically conveyed to undergraduate-level students. Indeed, countering a false sense of insular individualism and exposing the ironies of idealizing “freedom” from within a legal, social contract is necessary to fully understand the relationship between literature and politics in this period as well as to comprehend twenty-first century political beliefs and cultural practice. Asking undergraduates to challenge individualistic ideals is essential within arts and humanities programs, which continue to perpetuate a misleading Romantic ideal of the scholar as a competitively independent and exclusive individual genius. In a manner that replicates the state of our individualist professional practice, publication, and promotional evaluation, many university-level literature programs (at both the undergraduate and graduate level) offer classroom and program environments for students that discourage interdependent activities and accomplishments even though most faculty members must adopt collaborative and integrative practices in order to navigate everyday teaching, service, and research situations. To leave students unprepared for the promises and pitfalls of communal scholarly practice and mutual imposition is to leave them unprepared for the collaborative world that awaits them after their degree is earned.

MOOspace: Choosing an appropriate arena

To encourage the collaboration so necessary in today’s workforce and, more importantly, to help students confront the interdependent cultures, aesthetics, and politics of the Romantic era, I have appealed to the supplementary use of multiplayer online environments, which allow students to inhabit various social contexts rather than just abstractly understand them. These virtual spaces, like literary settings, offer an imaginary arena to showcase human drama. The difference between these environments and the worlds created through literary expression (and some traditional classroom practices) is that the player directly participates in the narrative, and players, unlike readers, can dream together in real-time, in the same space. While books can simulate such environments through representation, novels from this period do not enable readers to become characters in their stories, nor do they promote collaborative interactions between readers in bookspace. Designing specific stories and contexts for students to experience within these multi-user environments encourages co-operative play, inviting them not only to negotiate the tension between independence and collaborative life in the eighteenth century, but also to learn in a different way than they usually do in the humanities. Supplementing a traditional classroom space in which they are largely independent operators with the collaborative humanities laboratory of the multi-user gamespace is a worthwhile educational intervention. While many other collaborative classroom activities could be leveraged to encourage the same results without relying on computer and online technologies, this particular approach offers additional, valuable, and marketable learning experiences to humanities students regarding scripting, problem solving through program design and environment planning, order of operations, and working in a digital environment in general.

Digital gamespaces offer unique opportunities for designers and players: the designer is able to write the rules by which the story appears, as well as planning the story arc(s) (what Janet Murray calls procedural authorship (152)). Murray states that “the procedural author creates not just a set of scenes, but a world of narrative possibilities” (153), which is akin to a constructivist facilitation—a useful alternative to traditional teaching methods in which students are handed pre-rendered narrative syllabi and expected to follow along with the expert lecturer. Ian Bogost’s Persuasive Games (2007) extends this idea by recognizing that games employ a procedural rhetoric (i.e. persuasion through the authorship of rules of behavior, through a dynamic model). Players are required to contribute actively to their own progress within specific experiential fields in which choices and consequences have been pre-rendered for them. These affordances contribute to a rhetorical opportunity that can help to facilitate player identification with a designer-author’s intentions and ideas via performative participation.

The gamespaces that I have been using to engage undergraduate students with these ideas are hosted within a somewhat outdated environment as far as multiplayer game opportunities go, but which avoids obsolescence by remaining configurable, affordable, and textual. Acadia University’s gamespaces are built within enCore Xpress, an open-source MOO database and graphical user interface.

Since the MOO acronym might not be familiar to many readers, a brief history and explanation follows: MUDs (Multi-user Dungeons) appeared in the late 1970s and were the first multi-user online gamespaces. They used a text-based “chat room” interface to involve a number of simultaneous, networked computer users in role-playing situations within described environments that resembled early single-player text-adventure games like Zork. As MUDs evolved, ASCII graphics were added to some versions and their virtual spaces were harnessed by some users for educational ends. MOOs (MUD Object Oriented), the evolutionary cousins of MUDs, were born in the early 1990s and retained the text-based environment of MUDs but used an object-oriented programming language and a persistent object database to extend the flexibility and opportunities offered by MUD environments. Uniquely, users could also construct virtual environments from within those spaces via simple commands that eliminated the need for high-level programming knowledge.

Despite being over fifteen years old, the open-source accessibility, web-based aspect, multimedia opportunities, and programmability of the enCore Xpress MOO influenced my decision to utilize it for the purpose of delivering “serious,” multi-user games to my undergraduate Romantic-period literature students as part of their classroom experience.

Acadia University’s modified version of enCore Xpress, called Golgonooza (Blake’s city of the imagination), enables the creation and use of multiplayer, goal-oriented, persuasive role-playing games in my undergraduate classrooms. Its focused purpose and more developed toolkit takes it beyond the now defunct Romantic Circles MOO (Villa Diodati), which also used encore Xpress and which has no true pedagogical successor on the RC website. Golgonooza is also distinct from other computer-assisted pedagogical innovations. For example, Roger Whitson’s “William Blake and Media” class engaged students via Twitter, Zotero, and blogging activities, but none of these (individually or collectively) achieves the community and role-playing potential of enCore Xpress’ interactive story-world environment.

I have installed two versions of the encore MOO on Acadia’s servers. The first (http://moo.acadiau.ca:7000) is based on version 4 of enCore Xpress. This database (named Golgonooza) hosts a hardcoded gamespace based on the environments featured in Mary Robinson’s novel The Natural Daughter (1799). This game was designed by Beth Lyons (a former theatre undergraduate student), Jean-Marc Giffin (a former undergraduate Computer Science student at Acadia), and me. The other MOO installation (named Golgonooza 2.0 and found at http://moo.acadiau.ca:7001) has been customized to host persuasive arguments in the form of interactive digital gamespaces that are created by students in my year-long, undergraduate Romantic-period literature course.

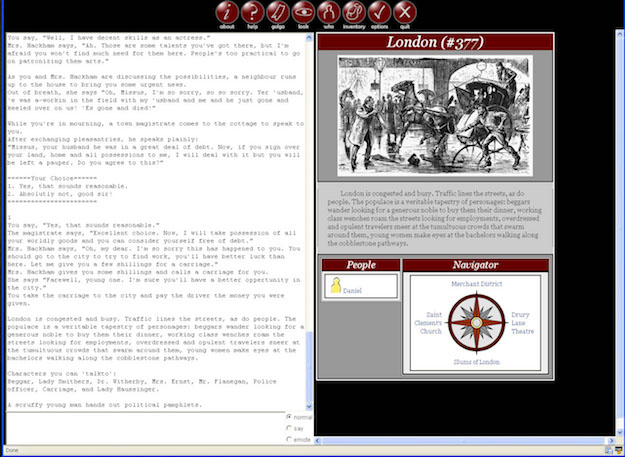

Both Acadia versions of enCore Xpress have been extensively customized through a collaborative effort between myself and Jean-Marc Giffin. Together, we have designed and implemented a few unique affordances that distinguish Golgonooza 2.0 from other installations of enCore Xpress: our modified version of enCore features a game design toolkit that uses a GUI to allow the user to create a system of navigable, interconnected locations and to populate those locations with objects and non-player character bots that can “converse” with the player. Entrances and exits can be customized to facilitate one-way travel, to defy the logic of compass-based navigation, or to be invisible until players receive certain objects or information. Objects, characters and locations can be customized and augmented through textual descriptions, audio, images and video. NPCs (non-player characters) can be static or programmed to wander on random or scripted paths throughout the gameworld. Interactions with NPC’s are managed through conversation tree scripts. Different scripts can be written for different interactions (based on the player’s class or gender), and this scripting can be used to give NPC’s “memories” of previous encounters with the player (Figure 1).

Fig. 1 A screenshot of Golgonooza’s The Natural Daughter game

Programmed: All the men and women merely players

The Natural Daughter Game

Golgonooza’s The Natural Daughter game is not a simple re-presentation of Robinson’s narrative or characters but is meant to question critically the individualistic triumph promoted by the novel’s overly optimistic conclusion and to raise questions about the tensions between realism and idealism in literature of the period. In other words, it builds upon the cultural critique begun but left unfinished in Robinson in order to help students perceive in a more robust and visceral fashion how late eighteenth-century social hierarchies and mores constrained individuals. After reading and discussing Robinson’s novel over a few weeks of class time, groups of two or three students log into the MOO environment using a single user account. The members of each team collaboratively contribute to their single character’s progress in a role-playing game that positions them as a woman in late-eighteenth-century England. Students are told that their goal is to become a “successful young woman.” This goal is intentionally vague, and remains open for interpretation, allowing the student teams to consider “success” in relation to the historical period that is being represented, to the parameters modeled in Robinson’s book (perseverance and ethical consistency against universal adversity), or to twenty-first century notions of “success” (such as self-determination, empowerment, independence, and equal opportunity). By collaboratively controlling a single character’s movement and dialogue, each team of student players are put in situations where they (playing as eighteenth-century women) experience social life at Bath, the difficulties of married (or single) life in rural and urban situations, and London’s opportunities and temptations.

Importantly, each player character’s class and social status are randomized variables that can change with each new playthrough. One’s class position initially establishes a specific level (or deficit) of social freedom and flexibility in the gameworld, and a player’s initial reputation (based on such social stereotypes) generates different responses and opportunities (or not) from other, non-player characters and the environment itself. Reputation remains a variable throughout the experience, though, and can be sullied or redeemed by one’s actions and choices while interacting with the game’s selection of fickle characters. Players quickly learn that whatever initial position they have in the gameworld as a result of their social class is precarious and that any interaction within such unstable environments can easily lead to a reduction, maintenance, or augmentation of this reputation. Thus, like Martha, the protagonist in Robinson’s novel, players often find themselves negotiating between individualistic ambitions and selfish desires, as well as between social responsibilities and co-operative sympathies.

What makes this experience more than just a participatory replay of the book’s narrative is that players cannot succeed by twenty-first-century standards, and, given that they are not allowed to replicate the success of the novel’s idealistic conclusion, in which Martha’s individualistic determination allows her to persevere through hyperbolic adversity and marry the “right” man, they cannot succeed by Robinson’s Romantic standards either. The “best” ending that a player can achieve is to be married to a husband who provides financial stability but little emotional support. The character becomes stuck in a type of limbo where she is faced with few opportunities, growing ennui, and a husband who dismisses her as if she was another one of his servants. This particular end in the game does not equal freedom, but is the achievement of a sort of life-in-death that recalls the personal Hell experienced by Coleridge’s ancient mariner (though the mariner still possessed the poetic power to affect others and could still tell his tale, whereas the players of this game are much more disabled). Achieving such ends exposes student-players to circumstances that parallel the experiences of women in late-eighteenth-century England: any accomplishment is still circumscribed by the rules and inherent limitations of a largely unsympathetic and restrictive system. Overall, then, this game encourages students to performatively interrogate and problematize the kind of individualistic strategy that Robinson’s protagonist chooses, but it also raises questions about the nature and limits of interdependence in this period. The game world and its rule systems are mechanical, unsympathetic, and frustrating for the idealistic player, and limited choices masquerading as freedom reveal the difficulty of choosing one’s own adventure in a consequential universe.

This circumscribed setup allows students to empathize with the cultural milieu in which Martha operates, as well as to consider the broader emotional aims of narrative itself. Given that most commercially available digital games cater to the pleasure of the player (and consumer), students familiar with this storytelling medium will be surprised that this example takes an antagonistic position toward the player’s success. Yet, this frustration is instructive, as it teaches greater awareness of both the cultural limitations within Romantic-era society and of the amelioration afforded by narrative, both then and now. This game enacts Katie Salen’s and Eric Zimmerman’s useful definition of “play” (“free movement within a more rigid structure” (304)) quite literally, demonstrating in its story and in its mechanics that:

- Limited flexibility is not freedom.

- The player, like a reader, is not authoritative, despite the deceptive appearance of agency and choice within game systems.

- Digital games can be used for social, political and psychological confrontations as well as for escape.

This experience also presents a challenge to and rejection of the often solitary nature of gameplay, scholarship, and the privacy of traditional readership by asking a group of students to be responsible for a single avatar’s progress. Team-based play continually engages players in dialogue, collaboration, and co-operation as they work through individual differences for the good of their single player-character.

In the last four years of using this game in my undergraduate Romantic-period literature classroom, I have found that students still have “fun” with this game (and here I rely on Raph Koster’s definition of “fun” as the opposite of boring (42)), but are not satisfied with the experience due to their unrealistic expectations for success generated by Robinson’s novel. This attests to the effectiveness of game-based pedagogy, as the purpose behind the creation and implementation of these game experiences is not to entertain the students, but to facilitate a memorable learning experience by generating a dissonance between expectation and experience in a supportive classroom environment. Postmortem discussions with students have resulted in excellent opportunities to comparatively examine the social function of the novel in the Romantic period. For example, the idealism and sentimentalism that problematize Robinson’s proto-feminist narrative are exposed and questioned though the contrasting pessimism built into the game’s world. The fact that both novel and game explore the relationship between independent motivations and intentions enacted within interdependent environments creates an important thematic link, which fuels classroom discussions. The key here is that student-players encounter and critically examine Robinson’s novel through traditional classroom lectures, discussions and debates, but also augment and enrich such experience by performatively negotiating with and metacritically engaging with Robinson’s ideas within a multiplayer gamespace. Making use of simulated experiences and follow-up discussions about those experiences fosters extended learning opportunities that supplement the existing opportunities that come from a critical reading of the novel. Any dissatisfaction and reluctance that might accompany the use of the technology, amplified by the game’s inherent difficulty, creates an overall environment of frustration, an arena in which players are brought closer to an understanding not only of women’s growing dissatisfaction during this period of burgeoning individualism in British history, but also of the philosophical, psychological and social paradoxes that reside at the heart of the period’s uncertain cultural expressions.

Endgame: Playing with Fiction

Games are not “ethics-free” environments. Like novels, they are virtual spaces in which human beings are exposed to the consequences of action and conflict within larger social, political, and economic systems. Games allow readers to become players, which generates the potential for sympathetic understanding, empathetic engagement, and a chance to experience the ways that an environment is impacted by their choices in the safe, non-fatal frame of a classroom activity. This interactive narrative challenges the period’s fiction and the students’ perceptions of that fiction within equally fictional environments. It engages students in thoughtful play that lifts the painted veil from romantic mediations via a game-based mise en abyme that exposes the limits of fictionally constructed expectation and places the player in a persistent tension between independent and interdependent action that is not achieved through reading alone. In contrast to the idea that digital games promote thoughtless reflex and complicity within pre-rendered systems, it is possible to use such environments to generate an essential lucidity and experiential unease that catalyzes thought-full awareness and critical reflections. Questioning the limits and opportunities of fictions and mediating structures from within such fictions and structures is the ultimate aim of such play.

It could be argued that one does not need to appeal to technology to achieve such pedagogical ends. Traditional group work, staged debates, role-playing exercises and even custom-developed tabletop games could all be harnessed to produce a similar effect. This is certainly true, but my overall point is that the Natural Daughter MOO game has generated useful in-class discussions regarding general ideas, such as comparing the technological aspects of book-based and computer-based storytelling and the position and power of readers versus players. More specifically, though, this experience never fails to catalyze engaging discussions that apply Romantic-period contexts to students’ understanding of themselves and their contemporary experiences. In addition to a heated debate about the way that eighteenth-century novels and twenty-first-century digital games have both been accused of individually isolating and socially networking their audiences, I have also witnessed a lengthy classroom discussion regarding the parallels between the way that inventive and innovative experimentation in the Romantic period diversified the creative landscape but led to tensions between imagination and nostalgia, and the ways that revolutionary transitions in our current media landscape interrupt our habits and generate similar reactions. However, the most important learning opportunity that emerges from utilizing such digital gamespaces in the Romantics classroom appears when student players are asked to become builders within the MOO environment.

Programmers: Extending collaborative creativity from players to builders

In my year-long undergraduate Romantics course, the use of the MOO platform is extended towards a completely different end in the second term: it becomes an environment in which students complete a group assignment that asks them to collaboratively build a persuasive, rhetorically argumentative gamespace related to specific course readings. To turn students from readers (consumers) to players (participants) to builders (creators) is to empower them and to promote an understanding of the ways that media can shape understanding and action. This project is a twenty-first-century extension of the revolutionary kinds of media-based awareness and agency that creators and consumers were experiencing in the Romantic period.

To make room for this project in the syllabus, I replace two essay assignments (out of the six that I normally assign) with a digital game development project in which students collaboratively design and build non-linear, interactive narrative gamespaces within the MOO using a simple but robust GUI (Graphical User Interface) developer toolkit. This is beneficial because it introduces students to programming structures through the customization of branching story opportunities and the population of a virtual environment with scripted NPC conversation “bots,” and objects, but does not require them to learn a programming language to accomplish this. By simplifying the tools available to students through the use of a GUI, I can expose them to modding and customizing practices that involve branching narrative scripts without bottlenecking their potential to deliver a rich, collaborative result (see figures 2 and 3).

Fig. 2 The Resource Management GUI for student projects in Golgonooza 2.0

Fig. 3 The flexible and robust script editor GUI for the creation of conversations that players can have with non-player characters in student-designed gamespaces. Note that no computer programming is necessary to create these scripts, but the process of scripting multiple paths emulates the kinds of instructional processes that programmers engage in.

The normal vehicle for student work and evaluation in undergraduate humanities courses is—of course—the rhetorical essay. While this is a tried-and-true method of critical expression, and one that I continue to use in my Romantics classes, the essay is only one form of argumentative communication, and students—unfortunately—learn to take the form for granted at the same time as they become more proficient at adapting their ideas to its formal constraints. Moreover, the essay format offers a time-limited value, as many students will enter a workplace that requires them to communicate in multimedia formats. Our increasingly diverse media landscape, amplified by the accessibility of digital technologies, has established an urgent educational need for multiple and integrated media literacies, transmedia awareness, and a working, hands-on knowledge of comparative media and cultural studies ideas and practices. Although consuming and thinking about class material is important, the productive and creative energies generated in response to such material should not have to be exclusively limited to traditional paradigms. Although the novelty of inserting a game development process into an upper-level undergraduate course disconcerts many students who feel that they have already mastered the algorithms at the heart of undergraduate assignments, it is in essence a refreshing opportunity for students to reconsider exactly what an essay does and how it accomplishes its persuasive argumentation in comparison to a playable space in which players need to be directed toward an acceptance of the same ideas as essay readers.

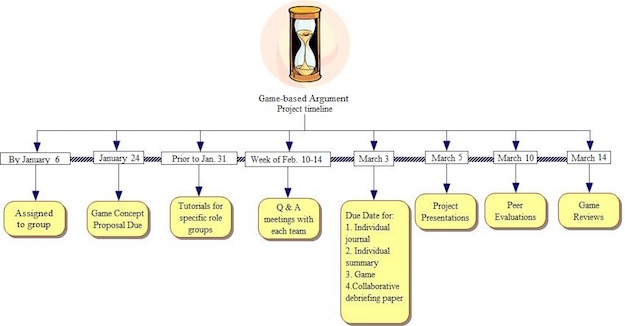

At the beginning of January, students receive the project briefing and the required development timeline (see figure 4).

Fig. 4 A sample project timeline schedule.

Early on, students are reminded that “Your players will not be playing a game based on a poem, play, or novel, but will progress through an experiential architecture that performatively exposes them to an argument relating to that literary work.” In other words, these games possess the same argumentative function as a traditional essay, but students need to import and adapt familiar forms and functions of rhetorical communication to a radically different environment. While part of rhetorical writing is to encourage one’s reader to keep reading, and while the act of reading implies at least a willingness to engage with the author’s ideas, the reading process is not as participatory (or as potentially powerful) as a player’s progress: whereas readers (in most cases) simply watch the author build a rhetorically sound argumentative structure and populate it with proof, players are asked to build the structure and gather the proof themselves, as directed by the game designer. Such participatory preconditions offer an advantage to game designers who are trying to encourage certain actions, behaviors, or beliefs in their players. As a result, games have the potential to be an extremely effective rhetorical medium: staging a convincing argument by leading a player through an active and concrete construction process, rather than—as is often done in essay writing—abstractly narrating such construction to a largely passive but still critical observer.

The grading rubric for this assignment calls attention to tensions and reconciliations between independent and interdependent work, expanding the thematic explorations from the gameplay that students experienced in the first term by putting students in situations where they must accommodate their individual differences to a collaborative working environment. Individual student assessment is based on a combination of individual contributions and group grades. This approach is specifically designed so that students must depend equally on their own abilities and their group’s performance (preventing an over-reliance on either). Productively, it allows students who might feel restrained by their group’s performance to augment such shortcomings by asserting their individual abilities, and conversely allows students who might lack such individual genius to assert their competency in group-related activities. In this way, collaboration, co-operation, and selfless reliance are fundamentally encouraged by this project: no one student could possibly complete the requirements on their own, so groups are responsible for self-organization and the delegation and management of roles and responsibilities (with guidance and mentorship from me during the process). Over the four years of incorporating this into my curriculum, I have discovered that letting go of individual control is very difficult for some of these students, as many have never been exposed to substantial collaborative, graded work at the university level. Actively confronting complexities together through building and making things (rather than just reacting to already-built things) while avoiding reductive and idealistic activities performatively reinforces the model of creative and critical networking at the heart of Romantic-period invention.

This assignment in which players become part of a community of builders who collaboratively work towards the same goal involves individualistic capabilities in a co-operative sphere, performatively engaging students in a synthesis of independent thinking and interdependent practice. In this way, students are more directly exposed to the opportunities and difficulties that arose during Romantic period collaborations fuelled by independent energies, such as the invention of the Lyrical Ballads or the creation of the French Declaration of The Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Such an experience does not just provide students with a chance to learn about the connection between independence and interdependence during this historical period; it involves them in experiential situations (as players/classroom citizens and as builders/authors) that allow them to more directly understand the intersections between collaborative challenges and individual inspirations experienced by Romantic period writers.

Extensions: Golgonooza will never be finished

In the first year that I introduced gameplay to the class, student groups could choose to focus on creating a critical interpretative argument relating to Byron’s “Manfred,” Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, or Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” or “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Notably, the “Kubla Khan” group used their gamespace to question Coleridge’s imaginative theories and visions through unsettling situations and unpredictable NPCs while still allowing the player to indulge in them. Their game expanded on and also offered a critical perception of “Kubla Khan”’s thematic possibilities, its drug-fuelled origins, and its fragmentary nature. While certain groups and individuals performed more strongly and effectively in this assignment’s first iteration, all students were able to bring individual strengths to bear on their collaborative creations, resulting in richly realized environments, characters, and narratives.

In an effort to create an opportunity for idea exchanges between groups (not just within them), the second year of this assignment’s implementation focused on a single author. I asked students to select one of Keats’s 1819 odes and to create a persuasive gamespace that allowed the player performatively to engage with a critical argument made by the design group about their chosen ode. Additionally (unlike the previous year’s selections), the odes that students chose for their projects were not part of the course curriculum and were not taught or discussed in class, thus offering the students a greater level of independence in the interpretative process.

During the 2012-2013 academic year and inspired by the conference version of this paper presented at NASSR 2011, I further refined the assignment beyond a focus on individual literary works, asking student groups to establish an argument in gamespace that asserted a conclusive thesis about the thematic tensions between independence and interdependence in Romantic-period writing, choosing literary examples from the course syllabus. Unifying all of the student groups under this thematic banner allowed for a post-mortem that related more specifically to the larger course themes and also allowed students to draw from on their own experience during the assignment’s creation and completion to inform their in-game argument.

Last year, I drew from class discussions that questioned the absence of specifically targeted “duties” and responsibilities within the National Assembly of France’s 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen by asking students to create a game-based argument that explored the tension between rights and duties during the Romantic period. This year, I have asked students to extend the debate between Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft, William Godwin, and Edmund Burke relating to the distinction between people and principles. After this year’s work is complete, the Golgonooza 2.0 MOO will host five years’ worth of student projects. Unlike essay assignments that generally trace a single line of communication between professor and student in a very specific and limited temporal frame, all of the student work in the MOO remains archived and publically accessible.

Sturm und Drang: Revealing resistance

Some students vehemently oppose the nature of this assignment, as well as the requirement that they work in groups (thus subjecting their course grades to the influence of variable group dynamics). During the first year’s assignment one student, who consistently refused to work as a member of a team, complained to my Department Chair that this non-traditional assignment was threatening to disrupt his accrued GPA and was not why he was taking English literature courses. During the second year of the assignment, another student decided to disappear for the duration of the project, but continued to log into the gamespace toolkit and re-design (or vandalize) his teammates’ efforts with ideas that he had not discussed with his group. This vandalism became so disruptive that I removed him from the team, and he dropped the course soon after. These extreme reactions are exceptions, but are also a reminder that issues relating to collaboration in creative and social contexts during the Romantic period remain relevant to young, creative minds in the twenty-first century. The MOO and the assignments constructed around the use of such a gamespace allow students to become performatively involved in the thematic issues that they are studying. Their varying reactions (excitement, curiosity, resistance, and discomfort) to new experiences near the end of an undergraduate career resist the abstraction and depersonalization at the heart of much academic work while at the same time allowing them to experience collaboration before confronting it in a professional setting post graduation.

Student feedback has convinced me of the overall value and necessity of this sort of experience for the Romanticism classroom. Without fail, all participants (even those who enjoy game-based narratives) chronicle an initial discomfort related to the unfamiliar nature of the assignment and technology that is slowly replaced by engagement with their group and project. Since university learning should be safe yet uncomfortable (as student comfort indicates that education is merely reinforcing their accepted and habitual subject position rather than challenging it), it appears that working in groups is a necessary, supportive, and helpful antidote to students’ individual discomfort. While some students—such as those mentioned in the above paragraph—consistently have problems with giving up total control of the assignment to others, most students express a significant amount of satisfaction with the process, the product, and the way that this world-building exercise resonates with Romantic-period preoccupations and projects. One student commented that the unique nature of this project “shook up the university slump” she felt that she had been in during the final years of her program and was thankful that it allowed her to express herself “in a different way.” This cleansing of blunted perceptions via unsettling and unfamiliar situations that call for revolutionary and imaginative processes exposes students to the ways and means that a number of Romantic period “builders” creatively reacted to the tumultuous here and now of England in the late eighteenth century.

Technological Obsolescence: Game Over?

Many instructors who are reluctant to integrate digital apparatuses into their pedagogical toolkit cite the short-lived nature of hardware, software, and compatibility. Investing a considerable amount of time in the development of a tool or exercise, only to discover that it is incompatible with many students’ machines within a few years of implementation, understandably discourages enthusiastic innovation. However, this risk is worth taking, as using writing to reflect on writing can easily become an insular and uncritical process. As Jerome McGann suggests in Radiant Textuality: Literature After the World Wide Web (2004), “We no longer have to use books to study other books or texts” (168). The enCore Xpress platform was selected for flexibility and longevity, given its web-based delivery and its relative stability as a database, and our modified versions have successfully been migrated across servers at Acadia during infrastructure reconfigurations. Nonetheless, the MOO is no Grecian Urn—the “chat” frame of the webpage that the MOO generates relies on Java, which is becoming less common and thus less supported (and usually blocked by default) by most web browsers. As a result, students have had increasing technical difficulties using the MOO platform on their laptop computers over the past two years. Most of the time these issues can be solved by adding exceptions for certain websites within the Java configuration program and within particular browsers.

While rapid obsolescence is a constant problem for digital tools and resources, there are potential ways to work around this problem. We are currently looking into ways either to convert the MOO's Java-based frame into HTML, or—in the worst case scenario—to create a Virtual Machine “wrapper” (that is, to allow students to easily boot and run an older version of Linux with better compatibility with Java on their computers as a virtual machine). However, it is likely that the MOO will soon need to be retired and replaced. The crucial thing is not to abandon the ideas and methods that the technology enables. Unlike the now-defunct Villa Diodati MOO that has fallen into inaccessible ruins, with only its vast and trunkless introductory page standing as a reminder that there was ever something there, Golgonooza will never truly be a ghost town: it will continue to be an activated complex, an organic archive of the fruits of exceptional student motivation and imagination and a valuable record of a learning process that will continue to grow until more effective alternatives emerge. One possible extension of this idea beyond the computer screen and classroom walls that I am currently exploring is open source game-based narrative platforms for mobile devices that work by tethering game content to actual geographies in an augmented reality layer. When such alternatives become feasible, and as computer hardware, software and networks continue to evolve, I will continue to ensure that both versions of the Golgonooza MOO remain archived and accessible to the broader scholarly community.

Revolutionary returns: Teaching nightingales to harmonize and socialize

Attempting to engage students with the complexities, advantages, and difficulties faced by the intersection of independent and interdependent approaches to creativity, communication, and action during the Romantic period is not an easy task. Showing and telling methods are easy, but they leave learners disconnected from the ideas that are presented to them. Exposing them to historical contexts and thematic intricacies via interactive, participatory learning environments offers a uniquely involved opportunity—akin to a humanities “lab” space where controlled experimentation and exploration can take place. Making use of this technology for the specific assignments mentioned above has an additional benefit: students learn to innovate, create, share, and play together and are thus professionalized for a collaborative career. Involving them in team-based work that respects individual differences demonstrates an integrative approach to such apparent opposition without watering down the difficulty associated with both poles. These examples of technologically-enabled pedagogy ask students to be less “romantic” about the Romantic period and to recognise the interplay and tension between individual genius/independence and collaborative practice/interdependency at the heart of the lives and texts of the period’s authors.

Finally, to get students to reflect on the nature of the academic essay and argument by exposing them to an unfamiliar variation of this process is an invaluable lesson to learn in the latter years of an undergraduate education, when many of the paradigms of higher education have become habitual and naturalised. In doing so, students are able to reconsider the essay’s form and function, perceive its limitations and advantages, and better understand their authorial, critical roles in relation to the abilities of their readers. If my goal as an educator is to mentor students toward a thoughtful, perceptive, and critical lucidity regarding literary expression, communication, creativity, cultural production, and critical dialogue, then—whether or not students emerge from this experience hating the assignments (in which case an appreciation for the strengths of the essay form is renewed) or loving this alternative to essay argumentation (in which case an awareness of the limitations of the essay form is revealed)—the careful use of these gamespaces in the university-level classroom allows me to reach these goals, confront the challenges associated with effective teaching and specific course material, and “win” the pedagogical game by encouraging individual student players to level-up and become lucid, collaborative builders in the spirit of the Romantic period authors that they study.