Even after directing a dozen full productions of the plays of the Romantic period,

I continue to alter my teaching of production and performance with each new play. One reason for change is that each play brings its own peculiar set of demands on the cast. Another reason for change is that each new cast brings a different set of talents to be developed. A third factor is my own evolving attention to the characteristics of period acting.

As an introduction to the drama of 1780-1830, with emphasis on production and performance, English 97H: Romantic Drama. Production and Performance, includes practice in acting styles of the period (gesture, elocution, delivery), historical theater construction, period costumes, and stage design. Although a large number of theater majors, music majors, and English majors turn out, auditions are open to all students. They are asked to prepare a monologue, a song, and to provide a “cold” reading of a dramatic passage. In selecting the play to be performed each year, the primary concerns are to find a play that will challenge student abilities, that will be accessible to our audiences, that will be rich in historical relevance, and that will depict the temper and tastes of the period. Because the theater of the period is musical theater, there is also the difficulty of securing a musical score. Many productions relied on interpolated songs, and even where full scores exist, those score were often altered with changes in the cast from one season to the next. Obviously the music, then as now, had to suit the abilities of the cast.

As offered during the Winter Quarter (January through March) 2006, the course actually began with enrollment/auditions at the end of November in the preceding term. The course description was also the call to auditions.

Casting and stage crew assignments were completed the following week,

so that all participants had the play script and musical score over the December holidays. Rehearsals commenced immediately with beginning of the winter term, 7 to 10 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays 1st through 8th week, with additional vocal rehearsals on Wednesday evenings. Because the course aims at performance and production, the first eight weeks (of the ten-week quarter term) are spent in mastering the play, rehearsing, preparing costumes, set, and props, followed by two weeks to perform. Performances were scheduled at the end of the 8th week: UCLA, March 3, 4, matinee and evening of March 5; Cal State Long Beach, March 9.

The selection of the play to be performed each year is usually made during the preceding summer, when I have the opportunity to browse through the archives of the Theatre Museum in Covent Garden, London. During the summer of 2005 I came across The Haunted Tower, a Comic Opera, with the compete musical score by Stephen Storace (1763-1796)) and the libretto by James Cobb (1756-1818). Opening at Drury Lane November 24, 1789, this comic opera was a significant success, with eighty-four performances in its first two seasons, many more throughout the 1790s, and frequent revivals for the next half century.

For the purpose of this essay, it seemed useful to highlight a single production, so that a coherent set of examples could be provided for all aspects of our efforts in a single term.

The Haunted Tower provides an excellent example because of its particularly rich fabric of historical, social, theatrical, and musical issues. Having in previous years directed Elizabeth Inchbald’s Animal Magnetism and Hannah Cowley’s A Bold Stroke for a Husband, I was ready to prompt students to give special attention to disguise and role-playing as a dramatic means of exposing prejudicial assumptions about gender, class, and national character. The Haunted Tower proved a good choice both pedagogically and dramatically, providing insight into social issues, political tensions, national and international turmoil. The representation of English-French relations on the very eve of the Revolution would, in itself, amply justify the focus on The Haunted Tower. The fact that it is also a play adapted from the French of the Marquis de Sade for performance on the English stage gives it an added dimension of political complexity.

Discovering Storace and Cobb

Storace and Cobb began their collaboration with a translation of The Doctor and the Apothecary, which opened at Drury Lane on October 25, 1788. This production closely followed the Viennese original, Doktor und Apotheker (1786), with a score by Carl Ditters von Dittersdorf (1739-1799) and libretto by Gottlieb Stephanie (1741-1800). After the great success of The Haunted Tower, Cobb and Storace continued their collaboration with another comic opera, The Siege of Belgrade, first performed on January 1, 1791; The Pirates, performed at the King’s Theatre on November 21, 1792; and The Cherokee, performed December 20, 1794. In addition to his collaboration with Cobb, Storace also wrote the score for No Song No Supper, an opera in two acts by Prince Hoare (1755-1834), performed at Drury Lane April 16, 1790. For Hoare’s libretto Storace introduced some of the music that he had written in Venice of his opera, Gli equivoci (December 27, 1786), based on Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors. The music forGeorge Colman’s The Iron Chest (March 12, 1796) was also composed by Storace.

Although I was excited about working with a musical score that included 29 songs, with overture and finale, I also recognized that the music would be a challenge vocally to a student cast. The success was due to the Vocal Director, Stephen Pu, graduate student in Musicology at UCLA. In an attempt to trace the origin of the plot, and hoping to find hints on performance, I turned to Michael Kelly’s Reminiscences (1826). Kelly performed with the Storaces in Vienna and returned with them to London in March, 1787. Kelly made regular trips to Paris in search of material for the London stage. At the Comédie-Italienne in Paris, 1790, Kelly saw Raoul Barbe-Bleue, a comic opera by Ernest Modeste Grétry (1741–1813), with libretto by Michel-Jean Sedaine (1719-1797). Kelly not only persuaded George Colman to write an English adaptation, Kelly himself composed the musical score. Blue-Beard; or, Female Curiosity opened at Drury Lane on January 16, 1798.

Cobb's Adaptation of Sade

When Kelly made the trip to Paris in 1788, he returned with a work entitled, La tour enchantée, un opéra-comique. In searching for the author of this French work, I discovered that it was none other than the infamous Marquis de Sade, who had sent it, along with several other plays, to theaters in Paris in late summer, 1788.

This discovery was not mine. John and Ben Franceschina provide a comparison of the French and English versions in the introduction to their translation, The Plays of the Marquis de Sade, 3 vols. (2000). Serendipitously, I also discovered that UCLA’s Clark Library possessed a manuscript of Sade’s La tour enchantée and that the manuscript of Cobb’s libretto was in the Larpent Collection at the nearby Huntington Library.

During the Fall term I set to work with the necessary adaptations. First, I turned to Brian Holmes (San Jose State University) to adapt the musical score for performance by a chamber ensemble (violin, viola, flute, keyboard) rather than a full orchestra. Brian also provided an additional song for a scene that had been omitted by Cobb (“My love is not a problem” II.vi). This song is sung by a tax collector, whom two young ladies are trying to persuade to enter the Haunted Tower (“Attune the pipe” II.vi). The first week began with discussion of plot, character, and acting styles, and many improvisation exercises in period acting accompanied scene by scene blocking of the play. For the first several weeks vocal rehearsals were held separate from acting rehearsals, but because this production is so extensively musical, the two had to be integrated by the fourth week. Additional time was required for vocal rehearsals right up to the time of performance at the end of the eighth week. For our final dress/tech on Thursday, March 1, we had the benefit of an exclusive audience of specialists: Catherine Burroughs (Wells College), Jeff Cox (Colorado), and Jane Moody (York), who provided a useful critique following the performance.

The great advantage of utilizing performance and production in teaching Romantic Drama is that the students learn the material literally from the inside out. They gain an understanding of the language, the acting, and the music that mere reading cannot provide. With this particular play, the students were made aware of gender issues, as well as national tensions (French vs. English) and social tensions (aristocracy vs. lower classes) that prevailed during the period. As the only work of the Marquis de Sade to be performed on the London stage during his own lifetime, The Haunted Tower also gave students insight into the international reach of the drama of the period.

The Haunted Tower and its Historical Context

The task of rendering La tour enchantée palatable to an English audience was far more complicated than simply excising Sade’s comments about the English. Cobb had to tell the story from an English rather than a French perspective. He was greatly assisted in this task by Storace, who provided several set pieces to reinforce a sense of British tradition: an opening chorus “To Albion’s Genius” (I.i), a hunting song, “Hark! The sweet horn” (I.iii), a chorus to the “Roast Beef of Old England”(II.vii), and a drinking song praising English ale, “And now we're met, a jolly set” (III.iv).

Further, Cobb’s version, with its marriage between Lady Elinor de Courcy and Lord William, restored to his estate as the true Baron of Oakland, reestablishes harmony between France and England. The division between the aristocracy and the common folk is not overcome, but the virtues and advantages of the commoners are repeatedly affirmed. Indeed, the significant contribution of the subplot, the love of Edward and Adela, was to emphasize the sincerity and integrity of the lower classes. Michael Kelly declares that the subplot “was taken from an Italian intermezzo opera,” and it was clear that Stephen Storace intended the role of Adela as a showcase for his sister Anna Storace’s accomplishments, “both as a singer and an actress.” Kelly describes his own solos as Lord William, “From hope's fond dream” (I.i) and “Spirit of my sainted Sire” (III.iv), as “fine songs,” but notes that the latter was “one of the most difficult songs ever composed for the tenor voice.”

Revolutionary themes are incorporated but controverted: the corrupt aristocracy is overthrown, but the usurping Baron was only a fake aristocrat. The class hierarchy is topsy-turvy. In his endeavor to fulfill his father’s expectations as heir to the Baron’s estate, “plain Edward the ploughman” introduces his beloved Adela, a cottager, into court disguised as Lady Elinor. Meanwhile, to avoid the unwanted marriage, Lady Elinor pretends to be her own maid-in-waiting and Lord William passes himself off as a court jester. As jester, Lord William mocks the false Baron, who can only pretend to sexual attraction and prowess, but is still rich enough to pay for flattery and other services:

Whate'er your faults, in person, mind,(However gross) you chance to find,Yet why should you despair?Of flattery you must buy advice,You're rich enough to pay the price,5So that removes your care.

(“Tho’ time has from your lordship’s face” II.ii).

Several songs express the honesty and freedom of the lower class. Cicely, for example, sings of her freedom “From high birth and all its fetters” which allows her, in contrast to Lady Elinor who is bound in an arranged marriage, to choose the “youth I love” (III.iii). Edward and Adela ridicule aristocratic pretensions in their duet, “Will great lords and ladies” (I.iii). The conflict between upper and lower class is given full expression in the sestetto, “Alas! behold the silly maid” (II.iv), and more directly in the cat-fight duet with Adela and Lady Elinor, “Begone! I discharge you!” (III.iii).

As John and Ben Franceschina argue in the head note to their translation, a more persistent evidence of Cobb’s reliance on his source is “in the lyrics and situations of several songs that seem to serve parallel functions in both shows.”

Indeed, La tour enchantée provides prime evidence of Sade’s skill as lyricist, and Cobb followed Sade’s lead in his English adaptation. It was also to Cobb’s great advantage that he had the collaboration of Stephen Storace, whose score has been judged “the most successful full-length opera that Drury Lane staged in the entire century.”

Sade’s setting was contemporary. Cobb changed the setting back to the time of William the Conqueror. In adapting The Haunted Tower, I brought the time forward again to the reign of George III in order to make the references to the French Revolution more evident. Among other changes, I restored the opening dialogue between Juliette and Louise (Lady Elinor and Cicely), which provides at the very beginning of the play the explanation of the haunting. I also restored the scene in which an attempt is made to persuade Grouffignac, the tax collector, to enter the haunted tower. Here I made the further change of giving the task of seducing the tax collector to two village girls rather than to Juliette and Louise.

Much of the humor of the play derives from differences in manner and speech between French and English, and between upper and lower classes. These differences are compounded by the many role reversals. Having fled as a young boy to France, the exiled Lord William has survived as the Frenchman Sir Palamede, is concealed in the De Courcy estate dressed as a girl by Cicely, and presented at the English court as a Jester. In his role as the usurping Baron, Edmund the ploughman is boorishly clumsy in affecting grand airs, and obnoxious in his presumption of sexual liberties. To marry her beloved Edward, Adela must disguise herself as Lady Elinor, and Lady Elinor, to avoid marriage to Edward, pretends to be her own maid-in-waiting.

Period Acting and Gesture

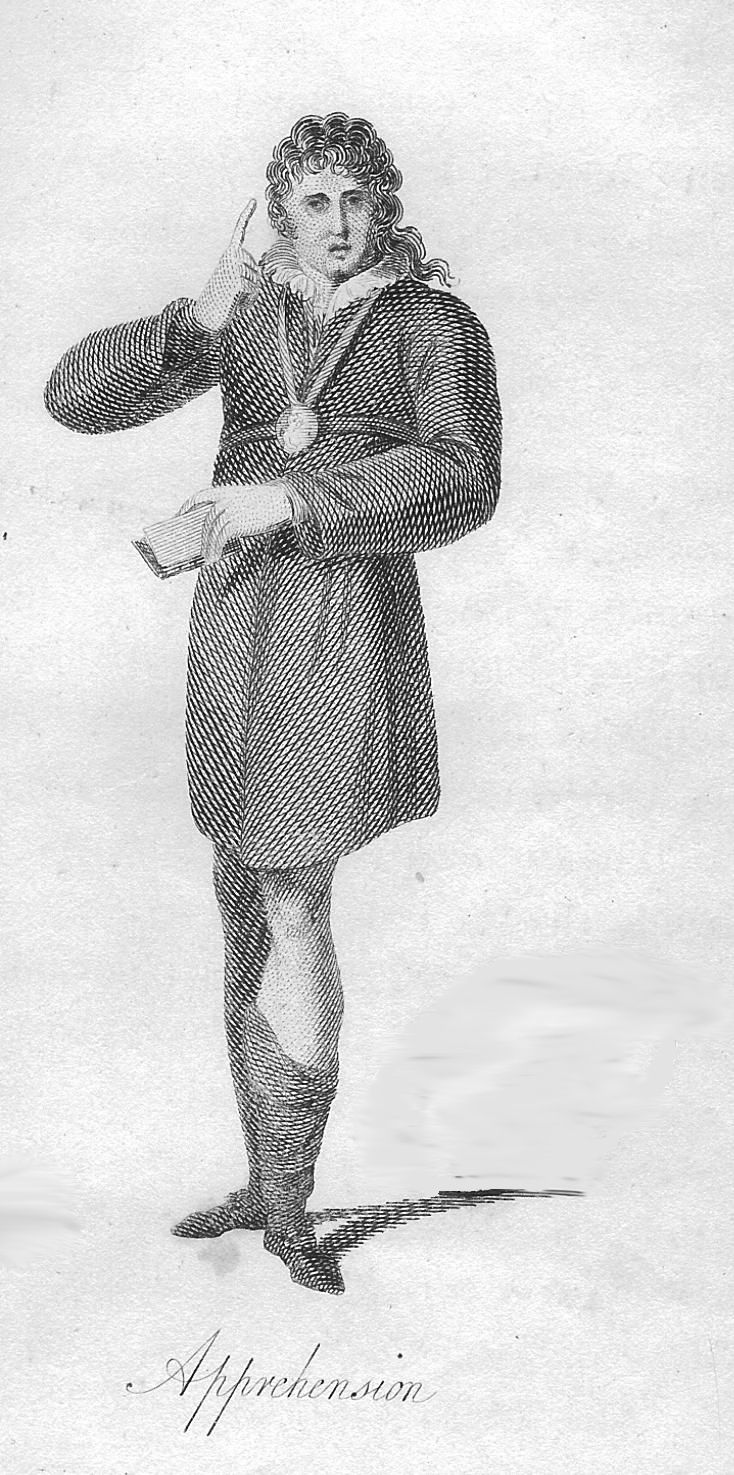

Practice in physical expression, “carriage and deportment,” were a part of the improvisational warm-up exercises at the beginning of each class. A major source on body language in the period is Johann Jacob Engel’s Ideen zu einer Mimik (1785). “Adapted to the English Drama” by Henry Siddons in Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action (1807; 2nd ed. 1822). Siddons retained Engel’s emphasis on “natural” gestures and augmented his commentary with cross-references to the English stage, with numerous examples drawn from the acting of John Philip Kemble and Sarah Siddons.

Anecdotal, yet with many well-delineated examples of the mannerisms of individual performers, Michael Kelly’s Reminiscences (1826) provides useful insights into character acting.

Many of the illustrations for the Boydell Shakespeare Gallery document stage gesture and movement,

and the Kemble Promptbooks give detailed information on blocking.

Typical improvisational exercises involved creating scenarios for selected poses among the sixty-nine plates from Engel/Siddons: Suspicion, Contempt, Pride, Phlegm, Hauteur, Doubt, Scorn, Astonishment, etc. In their initial reaction, students found the gestures highly stylized and artificial. The strangeness of period conventions, however, soon became familiar with practice. Typical of these exercises were the enactment Doubt and Apprehension in the manner of John Philip Kemble’s performance of Hamlet’s soliloquy:

Fig. 1 Apprehension, Engel/Siddons Plate 10

The pace and the movement of arms are synchronized with the movement of the mind: now moving slowly, now irregular, now agitated and quick. “The moment that a difficulty presents itself, the play of the hands entirely ceases – the eye, which, as well as the head, had a gentle and placid motion, while the thought was easy, and unfolded itself without labour, [...] in this new situation looks straight forward, and the load falls on the heart, until, after the first shock of doubt [...] suspended activity resumes its former walk.” The pace, the tilt of head, the movement of the hands and arms, must undergo a transformation from agitation to control. As if he catches himself, he stops still, gathers composure, then delivers his soliloquy. Hamlet’s reflections bring him to a crux: “To die, to sleep;/ To sleep, perchance to dream” (III.i). Hamlet comes to a full halt, pauses a moment, then exclaims “ay, there’s the rub,” and at the same moment should give the exterior sign of that which his interior penetration alone has enabled him to discover.

Set Design, Costume, and Performance

In spite of a strong commitment to recreating the conditions of Romantic performance, I make only a modest attempt to recreate stage designs and no attempt at all to imitate what was accomplished with traps, painted backdrops, wing-in-groove scenery, or the lamp lighting of the period.

Instead, I rely on conventional stage lighting, colored spots, and, as much as possible, single-set staging with a minimum use of larger props (tables, chairs). The set for The Haunted Tower, designed and constructed under the supervision of Jenna Murphy and her crew of five students, was based on the title-page copper-plate engraving by Simkins depicting the original setting for The Haunted Tower in 1790.

As may be seen in the photographs below, the set was dominated by a 17-foot haunted tower, flanked by flats with two gnarled trees on one side, and an arcade of pillars on the other. The tower featured an up-stairs window, from which a light flickered as cued in the script.

Those who were involved in costume design had the complex task of gleaning from source books costumes suitable for period, nationality, class, and trade.

It was important that the usurping false Baron of Oakland be represented in character and costume as crudely flamboyant. His costume was exaggeratedly ostentatious:

Fig. 2 Baron, Costume designed by Megan Correnti

By contrast, the French aristocrat De Courcy, brother to Lady Elinor, had to maintain a conservative dignity:

Fig. 3 De Courcy, Costume designed by Megan Correnti

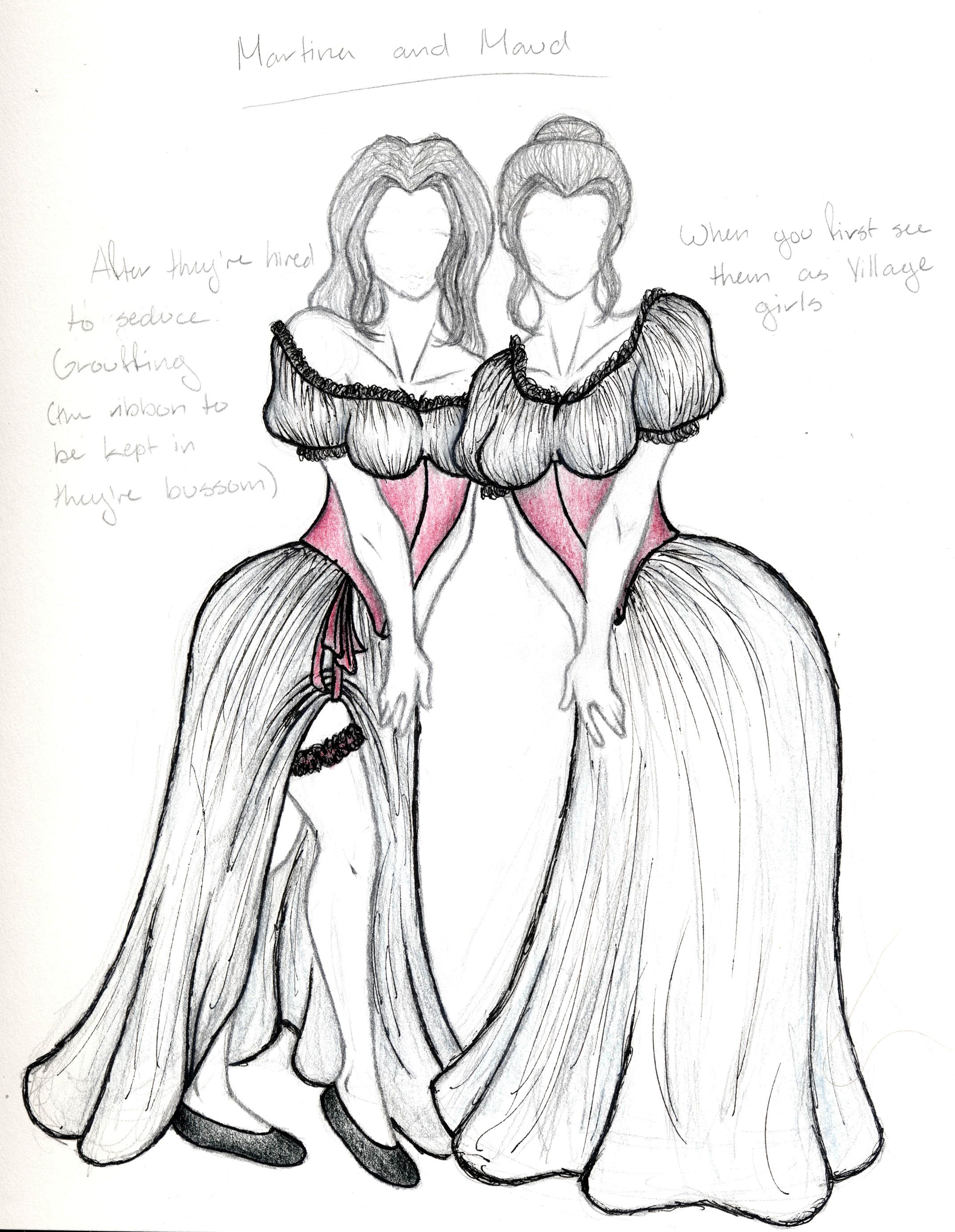

The village girls, Martina and Maud, are among the characters in the opening scene with arrival on the Kentish shore of the ship bearing Lady Elinor and her retinue from France. As the play opens, the two appear as modest peasants. In Act II, scene vi, however, they are called upon by the lecherous Baron to seduce Grouffing, the tax-collector, in order to persuade him to fetch the chest of gold stored in the haunted tower. For this scene, in which they sing “Attune the pipe,” their modest peasant dresses must be modified into seductive attire.

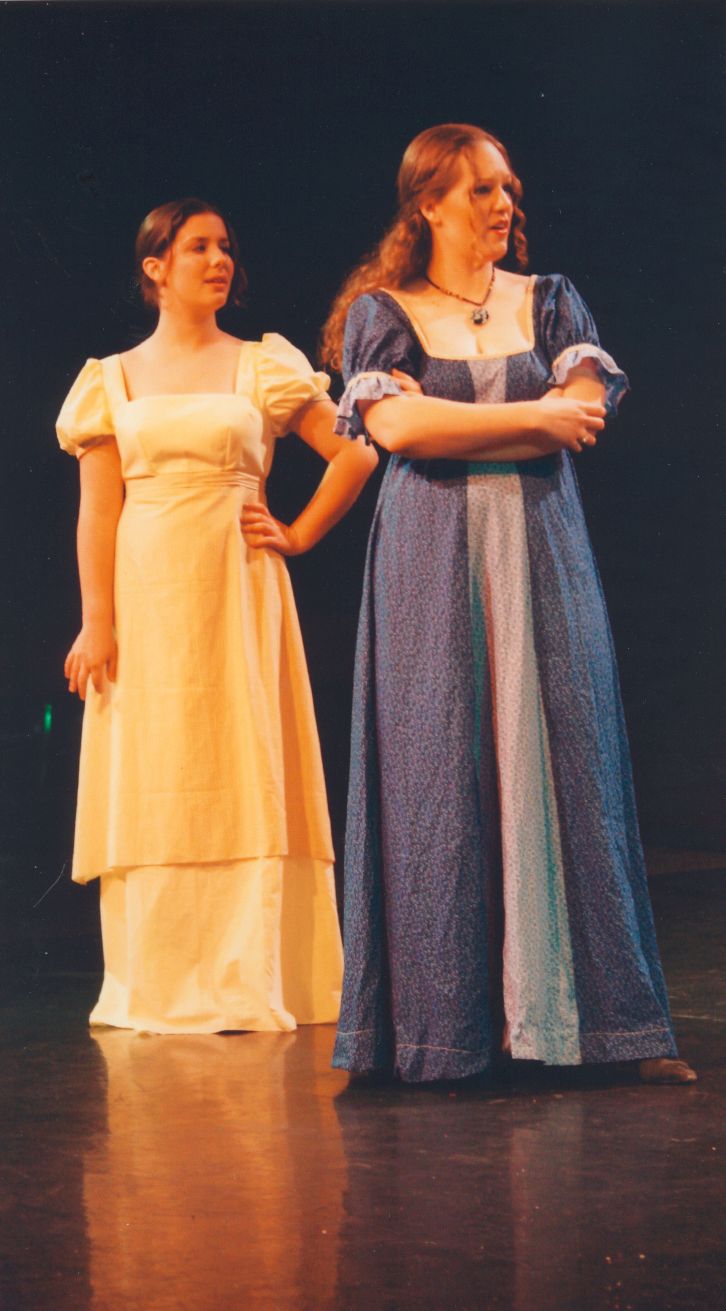

Fig. 4 Martina and Maud, Costumes designed by Megan Correnti

In the comedies of the period, an heiress and her maid are often depicted as companions: the lady demur and modest, the maid daring, witty, and saucy. The relationship between Lady Elinor and her maid Cicely adheres to this pattern, except that Cicely is several degrees more assertive and commanding. She constantly interrupts Lady Elinor, gives orders to Sir Palamede, and directs their actions. Her solo in Act I, “Nature to woman still so kind,” based on a Welch folk tune, asserts her sense of a woman’s advantage.

Fig. 5 Cicely and Lady Elinor (I.ii)

Although herself a member of the serving class, Cicely is haughty and officious when addressing other servants. In Act I, scene ii, as depicted, she is insulting in her rude dismissal of Maud, the village girl who has offered shelter and guidance to the newly arrived party from France. The gestures, it may be noted, are those prescribed by Engel/Siddons: Palamede’s contemplative curiosity, Maud’s offended astonishment, Cicely’s arrogant authority.

Fig. 6 Palamede, Maud, and Cicely (I.ii)

The role of Lord William is, in effect, several roles in one. He was but a boy of twelve when the false slander against his father, the Baron of Oakland, forced him into exile. Following the death of his father, a distant cousin, Edmund the ploughman, has seized power as usurping Baron. In France, William took on the disguise of Palamede, and matured into a promising young soldier in service to De Courcy. Here he fell in love with Lady Elinor and she with him. Her father, however, has pledged her in marriage to the heir of the Baron of Oakland. Lord William, of course, is the rightful heir, but he dare not make that claim until he has received the official pardon from the King. He thus must remain docile and submissive, even to the demands of Cicely. Assisting him to gain access to Lady Elinor’s quarters in her father’s estate, Cicely has disguised him as Lily, a maid-in-waiting. As Lily, William/Palamede was also able to make the crossing in the same ship with Lady Elinor. He is caught in the dilemma of asserting his masculinity while Cicely teasingly reminds him of his female role. Whatever other roles he is forced to assume, the audience must perceive that he is indeed his own man and capable heir to his father’s lands. When he steps forth from the haunted tower dressed in his father’s armor, singing the powerful aria, “Spirit of my sainted sire” (III.iv), he has fully assumed his proper heroic stature. The backflashes that explain the usurpation and exile are provided, first, by the village girl Maud, then by Hugo, faithful servant of the family. Cicely’s abrupt dismissal of Maud in the above depicted scene (I.ii) is motivated by her anxiety that she will lose control of the situation if Maud reveals too much of William’s eminent restoration. When William is introduced as De Courcy’s court jester, the Baron ridicules his debased status, but deftly turns the tables with a satirical song laughing at the Baron’s impotent and ineffectual prowess.

Fig. 7 The Huntsmen (Chorus) and Robert (I.iii)

As noted above, Cobb and Storace fortified the Englishness of their adaptation by introducing traditional English themes in their songs. How the entrance and exit of a chorus was managed at Drury Lane I could discover neither in Kelly’s account in his Reminiscences nor in Genest’s commentary on the premier performance.

My solution was to present a quartet (two sopranos, an alto, and a tenor) with changes in costume but always the same as characters. For the opening chorus (I.i) they were costumed as fishermen, as huntsmen led in song by Robert (I.iii), as servants to the false Baron (I.iii), as cooks, again led by Robert in singing the “Roast Beef of Old England”(II.vii), and as soldiers (I.iv and III.vi). The chorus thus had four costume changes, but they were instructed always to synchronize their movements and gestures, as in the above scene as huntsmen. The one exception was their signature entrance: they would march on stage perfectly coordinated, then stumble and bump into each other when they came to a halt.

Fig. 8 De Courcy and the Baron (III.i)

The comic center of The Haunted Tower is the lecherous and self-aggrandizing fake Baron. He exploits and abuses the lower classes as mere objects of his desires. Just clever enough to be aware of his own clumsiness in pretending to nobility, he constantly suspects that others of rank and power are laughing at his pretensions and attempting to undermine his authority. His suspicions are not ill-founded. In the scene depicted above (III.i), the Baron expresses to De Courcy his fears that a revolution, led by De Courcy’s court jester, is at hand. De Courcy, of course, perceives that the court jester is Sir Palamede, one of his own retinue. He knows Palamede’s affections for his sister, yet he has assumed that Lady Elinor would not dishonor her father’s pledge that she marry the son of the Baron of Oakland. In performing the role of the false Baron, Greg Cragg followed my cues in adapting several of Robert Baddeley’s mannerisms, including what Michael Kelly described as Baddeley’s “habit of smacking his lips always when speaking.”

In this performance the Baron’s lip-smacking made his words seem all the more lecherous. In the early scenes he performed his entrances with a pompous strut.

Only when he realizes that he is under siege by the rightful heir of Oakland does his pretentious “Hauteur” lapse into distraught fear.

Fig. 9 Edward, Adela, and the Baron (III.i)

At the beginning of Act III, De Courcy finally meets Adela, the peasant girl who has been impersonating his sister. Edward, son of the false Baron, is in love with the peasant girl Adela. Just as Lady Elinor must accept her father’s decision that she marry the heir of the Baron of Oakland, Edward must comply with his father’s eager pursuit of the marriage which will lend legitimacy to his own claims of nobility. Edward contrives the plot to disguise Adela as Lady Elinor and thus consummate the marriage before the real Lady Elinor arrives. The real Lady Elinor arrives too early, but is readily persuaded by Cicely to play along with the hoax in order to escape an unwanted marriage to Edward. This scene commences with De Courcy in pursuit of Sir Palamede, whom he now fears has turned traitor and seeks to elope with his sister. After the false Baron informs him that a revolution is underway, Edward arrives half-drunk from his tryst with Adela, whom he has introduced into the Oakland court as Lady Elinor. Considering his sister’s honor insulted by Edward’s overly familiar claims of intimacy with “my wife that is to be,” De Courcy is about to draw his sword. At this moment Adela arrives, and is greeted as “Lady Elinor” by the Baron and his son. Suspecting that this false identity must be a plot of Palamede’s, De Courcy declares, “I perceive, my lord, you have been imposed on, but you shall soon be avenged.” Edward and Adela stand aside looking guilty and exposed, while the Baron tries to puzzle out how he might have been “imposed on.” Not suspecting his son’s ruse and unable to determine any source of imposition, he follows after De Courcy to “ask whether I ought to be in a passion or not.” The scene closes with Adela singing a plaintive love song to Edward, “Love from the heart” (III.i). In referring to the penultimate scene (III.v), when “the Baron enters with his sword drawn, and some old armour awkwardly put on,” Genest cites Hannah Cowley’s remarks on Baddeley’s performance: “a great actor, holding a sword in his left hand, and making awkward passes with it, charms the audience; and brings down such applauses as the bewitching dialogue of Farquhar pants for in vain.”

The implication would seem to be that by some degradation of popular taste, the comedy of gesture has gained an unwarranted advantage over the comedy of witty dialogue. The charge is not without truth: Romantic comedy is not particularly noted for its clever dialogue, and it does rely frequently on body language, indeed more and more so with the increasing popularity of pantomime and melodrama. But this was not a passing phase. The Baron frantically waving his sword still brings down the house. Nevertheless it is also true that the dialogue contains a great deal of allusive irony concerning the politics of revolution.

Although the performers were well cued on pacing their delivery to allow that irony to emerge, many of the potential laugh-lines were missed by the student audiences during our four performances at UCLA. The cast and crew were therefore pleased and surprised by the much more responsive audience of literary scholars attending the performance on March 9, at the 41st Annual Comparative Literature Conference, California State University, Long Beach. The success of our performances were due entirely to the talent and dedication of the students involved. Gifted singers like Schuyler Hudak as Adela, Kristin Crawford as Lady Elinor, and Lauren Cheak as Cicely brought Storace’s score to life, and Stephen Pu as vocal director enabled the entire cast to achieve excellence in virtuoso solos as well as complex choral pieces.

In the final scene (III.vi), Lord William is revealed as rightful Baron of Oakland. He reconciled with De Courcy who affirms that no obstacle interferes with his father’s pledge of Lady Elinor’s hand in marriage. Edward is free to marry Adela. The comic opera concludes with the first Grand Finale to be performed on a London Stage:

The banished ills of heretoforeAt happy distance viewing;Of the past we’ll think no more,While future bliss pursing.

(III.vi)

Crucial here is that Lord William exonerates the false Baron of all crimes related to his usurpation and committed under his rule. The “happy ending” reconciles French-English animosities and class conflict at the very moment in history, immediately following the outbreak of the French Revolution, when these tensions were at a peak. Whether or not the audience saw any contemporary relevance in this doctrine of reconciliation, the finale gave an optimistic “feel good” conclusion to a comedy of disguise, deceit, and sadistic exploitation.