In spring 2007, I taught a special topics course at Shippensburg University with the same title as this essay. In the course, I examined with students both the dramatic writing of women writers of the British seventeenth through twentieth centuries and the meta-historical questions raised by the course’s title. In the following remarks, I suggest some of the directions that I tried in the course and some of the ideas I would try in the course after seeing how the students responded.

How: Tell the students to look for the plays written by women. Don’t just hand them to them; tell them that they have to go find one to read. Give them a time frame; maybe (or maybe not) suggest particular playwrights. Maybe gesture towards a reference source…but don’t hand it to them.

Why: Students may be surprised to find that it might not be easy to find a text to read. Much depends on what kind of library they use, whether they mind reading text online, how adroit they are in digging into online tools to find scanned texts. When I first taught this course in 2007, the landscape was quite different online. Then, the Googlebooks phenomenon took off, and now there are many, many relevant texts online. But regardless of what students find, their various paths to finding texts to read…and what they find and choose to read…provide a basis for good discussion about why these texts have the status they have, what the history of their publication has been, and how the students made their decisions about how to excavate the history.

In other words, this is one of those cases where professorial expertise can productively be withheld for pedagogical purposes.

The plays found can be returned to a bit later for discussion of their style and content. There’s a good chance that “what women wrote about” may be represented in interesting patterns by what students will find hidden in plain sight. But you might ask them to make some guesses about what women wrote about in the era in question and why. If they’re catching on to your game, they may cannily resist, but no matter…you can ask them why they resist. Why, after all, shouldn’t the sample we find be used to determine what the larger phenomenon of women’s playwriting consists of? Hey, I thought this was a literature class, not social science.

H: Ask students to look for reviews of plays by women playwrights of the era you’re focusing on. Again, like looking for texts, they will encounter something of the landscape of available information. Depending on whether they go the route of publications or online resources, and depending on how they construct their searches, they may run into some frustrations. This assignment effectively encourages collaborative work and provides coaching and suggestions. Again, the idea is not simply to show them the best repositories of information you know. See what they find.

W: What students may find when they do this is that the double concealment of minimal productions and limited access to review information can make it seem that there are few plays by women playwrights of certain eras that have been produced. If this is what is found, you might ask students why they suppose so little information seems to be available. But if they find a few valuable sources, you might follow up by asking them to determine what purposes led to the creation of the source. Students might then begin to examine assumptions about how history comes to exist as an available resource for our use. A first assumption may be that “durability” (aesthetic, probably) creates the archive of information. But many of the resources they will find likely will exist for other reasons than that they survived and were gathered together. In fact, digital materials typically have their own sorts of purposes for existing and being maintained, and these can be productively examined. Pose the question to students, “How are the purposes of digital archives similar to or different from those of material archives?” The question might seem to stump them at first, but they can go back to some of what they found in their first two experiments, maybe in working groups, and examine the materials to see if they can find any clues.

H: Show them how women responded to the dramatic writing of other women in developing their own dramatic voices.

W: Women playwrights understood that the ways predecessor women navigated tricky genres, subjects, professional identities, and institutions had something to teach them. They may not have assumed that they should make the same choices as a woman dramatist who came before, but understanding earlier writers alerted Romantic-era playwrights to the distinctive gendered landscape they needed to navigate. Cowley looked back to Behn and Centlivre, as did Inchbald. Women who wrote tragedies and histories—from Burney to Baillie to Mitford—read widely in the unperformed published tragedies of other women.

H: Place women’s dramatic writing in the context of men’s writing of their era, in similar genres, and for the same theatrical houses and actors.

W: While women theatre writers may participate in a counter-tradition that has its own historical significance apart from their public recognition, how women dramatists wrote in relation to the male writers of their era provides a crucial lens through which to view women’s choices of form, subject, and social process. With men often in control of the business end of theatre management in the Romantic era (but not always, consider Jane Scott), women’s ways of “writing their way in” can be seen for all its pragmatic or self-assertive ingenuity. Some women playwrights—such as Inchbald—needed to succeed financially, while others had greater freedom to test the limits of male dramatic conventions—Baillie, for instance. But it is always worth considering how women dramatists position themselves in relation to men’s dramatic writing of their era. Doing so helps to estrange the aesthetic of the male tradition, to contextualize it historically, and at the same time to see the strategic dimension of women’s dramatic aesthetics.

H: Look at how women dramatists and actresses contributed to each other’s aesthetic and professional development.

W: In some ways, women dramatists and actresses were two aesthetic “species” that constituted the two aspects of the theatrical female of the Romantic era. While the dramatist could lay some claim to literary authority, the actress could sustain a kind of public persona through careful reputation management, self-marketing, and selection of repertoire. But, of course, the two different female theatrical roles also had ways of teaching each other. Actresses learned to “author” their theatrical personae from women dramatists, fashioning ways of developing their professional character performance by performance. Playwrights “performed” their authorship, learning from actresses how they might influence public perception through staging particular moments of authorial utterance within the public sphere. Even more fascinating, women dramatists wrote plays with particular actresses in mind—Baillie’s Jane DeMonfort for Siddons, for example—but even beyond practical casting considerations, actresses served to flesh out the imagination of the stage writing of women who wrote without intimate knowledge of the backstage world or who sought in the persona of an actress a way of moving beyond their own personal style of feminine performance. At the same time, actresses valued the roles written by women for women’s performance.

H: Consider the continuum of venues for which women wrote drama—from private circulation of closet drama to London’s patent theatres and all spaces in between.

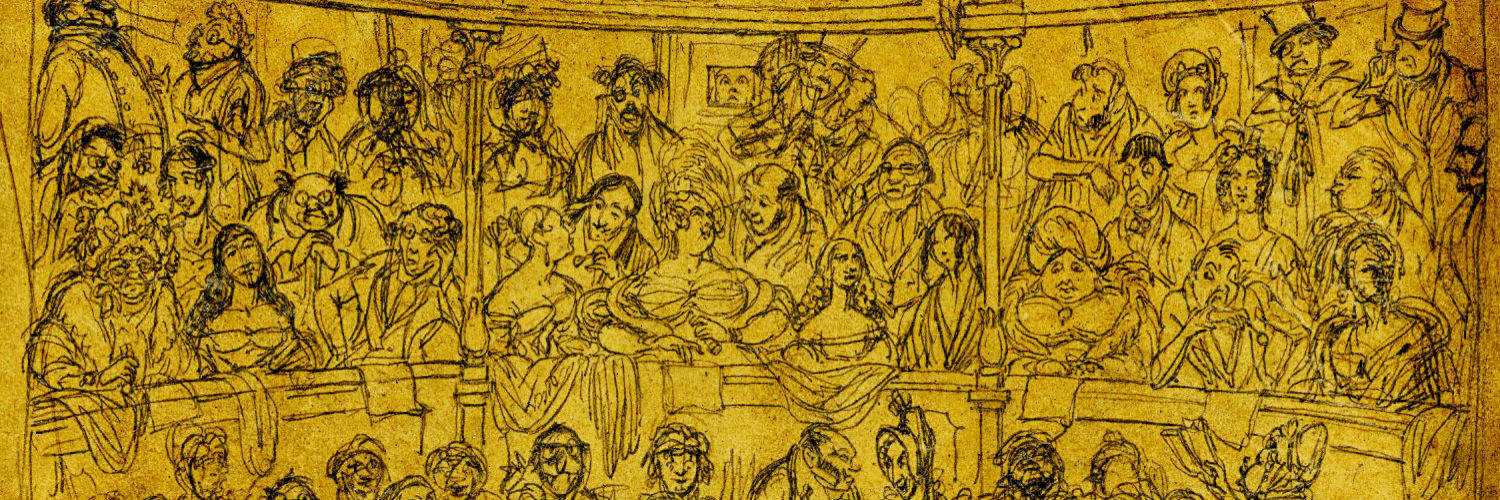

W: The early phase of research on women dramatists focused on the far extremes of these venues, the closet and the patent-theatre stage. But as a greater variety of scholarship has developed, more work on alternative London stages, provincial stages, private theatres, and any number of alternative venues has complicated the picture of women’s dramatic writing. What makes consideration of different venues such an interesting dimension of our historicization of women’s dramatic writing is that it forces us to reexamine dramatic forms and subjects in the context of variable social dimensions—which audiences directly experienced the works, in what contexts they experienced the works, and how a drama’s aesthetic reception was surrounded in varied ways by other forms of publicity, knowledge, and social circulation. For instance, a play like Ann Yearsley’s Earl Goodwin, performed in Bristol and Bath in 1789, hits its regional audience and local readers of newspapers differently than the same play might have had it been performed, as Yearsley originally hoped, on a London mainstage. The social acoustics of varied venues of performance affect how women’s plays are heard and how they resonate in the culture surrounding them.

H: Study the theatre theory women of the era wrote, not just as explanations of their dramatic praxis but also as further ways in which they performed in the theatre of authorship and in which they created new possibilities for dramatic thinking.

W: In any form of commentary on theatre or drama, women writers envision ways that plays might be received—empathically, ethically, politically. When Inchbald, for example, responds to the plays of women writers included in The British Theatre, she cannily does so as much as a characterized type of critic as she does as a private citizen. A reader of her commentary is thereby given a kind of stance to respond to: “This critic raises an eyebrow about this play’s moral commitments, but I might not share those concerns,” one might think. But in this stance taking, Inchbald opens up dialogue with the plays she discusses, and that dialogue with a play is an opening to further thought. Likewise, when Baillie—in all earnestness, it seems—critiques the practices of theatre production of her time, she, too, does more than propose an alternative production style. She reframes the very idea of theatrical convention, inviting us to consider what kinds of aesthetics of character, plot, and theme current practices advance.

H: Consider women’s dramatic writing as more than pragmatic literary professionalism—consider its psychological and self-revelatory dimensions and the ways it allowed for new kinds of envisioning by women to become public.

W: There are times when I reread one of Joanna Baillie’s plays and I suddenly can only see its monodramatic qualities. I see only Joanna—both her young and her older self—playing all the parts, reading all the lines, channeling all the emotions. And then I think about the psychological freedom that envisioning oneself acting the play on a London stage could have represented to her. And then I think about what imagining her doing so could have represented to a woman (or a man) reading the play. The pleasure of dashing one’s head against the side of the stage, of tossing a coffee cup to the floor, of comforting a distraught brother, of disarming a crazed rival! Baillie, like so many women dramatists of the era, had discovered the power of interventionist acting out.

H: Introduce contemporary women dramatists and writers who employ dramatic elements in all kinds of contemporary forms of writing.

W: In my course, I connected women dramatists of the Romantic era to contemporary screenwriters and graphic novelists. We looked at My So-Called Life, Winnie Holzman’s mid-1990s television series, as well as Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home. After reading many different women writers’ treatments of family life in dramatic form, these two uses of dramatic elements in very different media suggested interesting parallels. But perhaps more importantly, the contemporary works sent us back to re-see such features as Inchbald’s tonal shifts or Baillie’s social contexts for the passions. It is valuable to look back to see what came before, but sometimes what comes after sheds light on the forms and strategies of predecessor texts.

H: Ask whether teaching women’s dramatic writing of the British Romantic era has any curricular patterns in common with teaching other minority literatures.

W: One of the questions I raised repeatedly in the course had to do with what kinds of rationales we can use to justify the teaching of “minority literatures.” Because some of my students were English education majors, and because I think about the concerns of future and current teachers whenever I teach literature these days, I was curious to probe the rationales we use to bring new books into the book room, new texts and aesthetic forms into our classrooms. After all, school can often be about transmitting the received forms and aesthetics—how else to explain the fetishization of Ibsen’s A Doll House in American public high schools to the exclusion of almost all other 19th century European drama? Why change what we teach? I know that in a faculty-research-driven environment, faculty’s continuing quest for a new margin to explore can provide the answer. But when the default rationale is celebration of the already valued, and when the logistics of getting new texts before the students can be complicated, other rationales need to be explored—if not necessarily unproblematically endorsed. Why, after all, teach undergraduates a course in “How and Why to Teach the History of Women’s Dramatic Writing” in the first place? Why indeed….

This rationale would depend on the idea that literature is taught to represent the history of culture. Therefore, to give an accurate picture of history would demand that major producers of cultural forms must be part of what we consider in historical studies to get an accurate picture. This rationale depends, however, on viewing women’s dramatic writing as significantly varied from men’s in ways that make it represent something slightly different, a significant minority variation. And the overall rationale for literature teaching that undergirds this reason is a kind of representational politics of culture. Questions might be raised about whether within the vast scheme of things that is a British culture curriculum women’s plays—given how much many of them partake of the same industry protocols as men’s plays—are a significant and variant enough subset to merit special consideration. Would we teach women’s newswriting, television screenplays, and so forth? The representational rationale is one that has its limits, though when linked to more pragmatic reasons—such as allowing contemporary women who (might) write drama to reflect on women’s previous dramatic writing—can have power.

As I’ve already suggested, this rationale ultimately has to be addressed within the historical rationale as well. There, the question becomes whether women’s writing of drama is representative of anything distinct that must be accounted for. Here, elements of dramaturgy (central female characters given new agency, for example) and of thematic focus (the problematics of marriage, women’s filial obligations, social pressure toward respectability) provide the main reasons for studying the history of women’s drama. Of course, these elements may either be seen as essentially different from other drama for reasons of women’s fundamental differences in interests from men’s, or as primarily a market niche that women dramatists occupied. The primary dilemma for this rationale is that convenience sampling of women’s drama overall may be the only way to claim an essential difference. Considering only women's plays that differ from the main body of a period’s drama seems a good way to ensure minority status that is both misleading and limiting to fuller consideration of the plays.

I’ve saved this one for last because it seems to me most compelling. When we look closely at the plays of women dramatists and at their careers as writers, we are often forced to see the complex interplay between dramatic writer and historical situation in new ways. Sidestepping the sociology of dramatic authorship no longer makes sense—and we begin to wonder whether it ever did. Our current ideas about how art treats some of the themes familiar to us—love, tragedy, economic struggles, etc.—are often turned around. For instance, we may leave to doubt whether any love story can confidently be taken as representational of a particular persona’s situation rather than as a structural device for examining identity, desire, and social priorities within the rigors of an art form centered on enactment rather than reflection.

This last rationale seems to me most appealing when we talk about marriage comedies of playwrights such as Centlivre, Cowley, and Inchbald since our own insistence on love as a personal emotion and set of choices seems problematized when characters’ personal actions in sorting out love matters test our credulity at the same time they might make some wonder, “Why doesn’t she just…?” or “Her actions seem rather tortuous and tangled.” While we can certainly choose to see the actions of the plays as less authentic and real than our own (aren’t they?), we might also scent the ways that our own beliefs in the personal directness of love, achievement, and ethical character might be a bit less inevitable were we to look at them in their full context of actions over a lifetime. Plays by women often create this trouble closest to home.

H: Raise questions for students about how and why our teaching, curriculum, and research choose their focuses, define and pursue their purposes, and determine their successes or failures.

W: There is a certain tyranny in looking mainly forward in our humanities scholarship. Wait, how can I say that we mainly look forward? After all, isn’t our curriculum mostly about the past? In a way, we are never more neglectful of the past and how we constantly remake it than when we naturalize our work with cultural materials from the past that our scholarly and teaching practices remake. As we pursue our professions through working with the materials of earlier periods, we sometimes fail to ask, “Why these plays, these pedagogies, this curriculum?” Of course, it is not possible to remain perpetually meta-aware of the premises of our teaching and research, but returning again and again to the questions “How?” and “Why?” helps to keep us honest, alive to the possibilities of the past, and sensitive to the work our teaching and scholarship does today.