The Classroom Dramaturg

In most theater survey or dramatic literature classes, plays are treated as literature. The term “dramaturgy” never comes up, either as a theatrical discipline or as a critical tool for helping our students understand drama. I propose changing this situation, and I will use Hannah Cowley’s comic masterpiece, The Belle’s Stratagem (1780), to demonstrate how looking at plays from a dramaturgical perspective can provide both students and teachers with a more dynamic relationship to Romantic dramatic texts.

As a dramaturg, scholar, and teacher working with historical playwrights, I seek to bridge the worlds of the academy and the professional theater. I find my scholarly background imparts a rigor to my dramaturgy and my dramaturgical perspective colors my approach in the classroom. The job of the dramaturg, when working on an historic play, has many facets. The dramaturg must advocate for the necessarily absent author, educate the director, cast, designers and audience about the language and historic background of the play, and keep the production true to the integrity of the work, while at the same time keeping in mind the artistic, physical, and economic realities of the theater. As a dramaturg, I consider it most important that my students be aware that drama is a form of literature not meant primarily to be read but to be heard and seen.

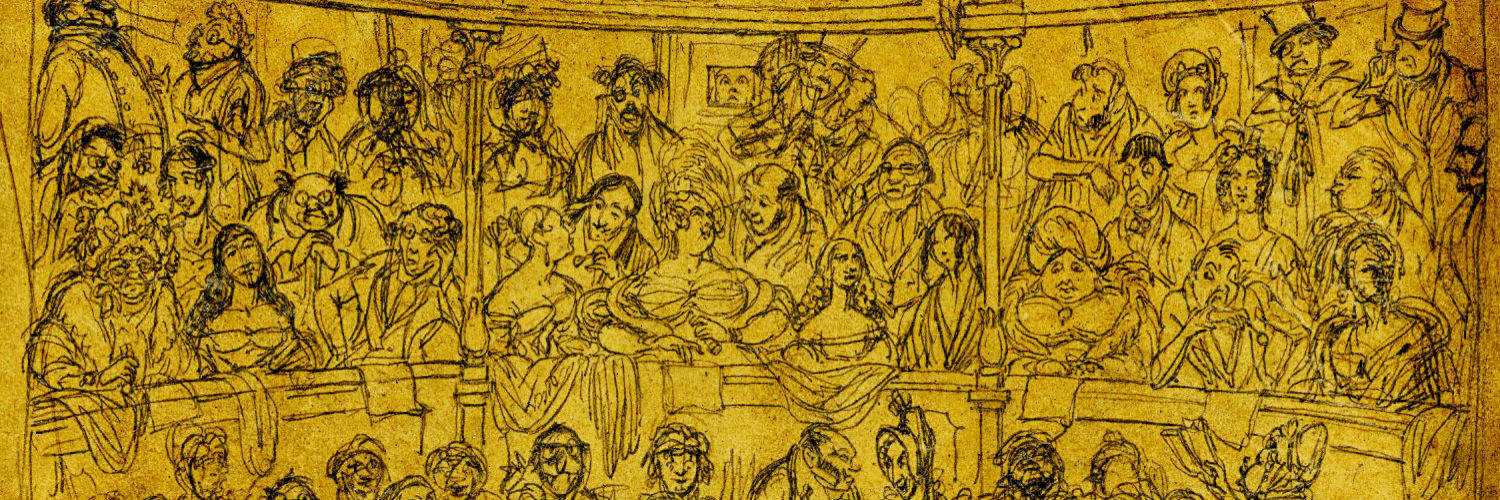

Theater is, by its very nature, a collaborative art. The text of a play is the skeleton, the bones of the work of art, that must be fleshed out by the joint efforts of actors, directors, designers, and even dramaturgs. The final collaborator is the audience. Every performance is individual and unrepeatable. Living, breathing actors embody a text and connect with a specific living, breathing audience, making the performance both a public and an intimate event. Part of a dramaturg’s function is to facilitate that connection. The dramaturg must always be asking, “What is the play’s relationship with the audience?”

To understand what that relationship is, more questions must be asked. What is left unsaid in the play? Are there assumptions the audience is supposed to make? Are these assumptions culturally or historically specific? If so, what can theater artists do to recreate the appropriate receptivity on the part of the audience? What are the silences in the play, the blanks in the script we must choose either to fill or elide, that will color our entire interpretation? (Whether we fill or elide these silences, we are making an interpretational choice, so we might as well make a conscious choice, while recognizing at the same time that other choices are equally possible.) How do we recognize the silences? All these are dramaturgical questions that broaden our understanding of a play beyond the simply literary perspective and lead us to a multidisciplinary approach to this art form that requires our active participation.

I propose to look at teaching Hannah Cowley’s comic masterpiece The Belle’s Stratagem (1780) from a dramaturgical perspective, and that means that the first task is to shatter the preconception that a Romantic play is a dusty period piece from a quaint and less sophisticated time. I want to get our students to recognize that the script is alive and subject to multiple interpretations. This can be demonstrated by showing how portraying a minor aspect of the play from different perspectives will change the resonance of the play for today’s audience, while remaining true to the integrity of the text.

On the Margins of The Belle’s Stratagem

While The Belle’s Stratagem is set firmly in the fashionable society of late eighteenth-century London, and its style is reminiscent of Cowley’s Restoration and Augustan predecessors, Cowley’s comedy demonstrates concerns about the laboring classes and their relationship to the moneyed elite. The title of Cowley’s comedy pays homage to one of her favorite Augustan playwrights, George Farquhar (1677-1707), and his The Beaux’s Stratagem (1707), and like many of these earlier comedies, The Belle’s Stratagem juxtaposes two story lines: Letitia Hardy’s ingenious plot to win the heart of her betrothed, Doricourt, against the marital problems of jealous Sir George Touchwood and his wife, the naïve Lady Frances. Both plots concern men learning to respect the women in their lives both before and after marriage, and are further connected by questions regarding the nature and fluidity of identity. Interwoven with these plots are transitional scenes among servants, tradesmen and con artists who make their livings off the excesses of fashionable life.

The title plot revolves around Letitia Hardy and her fiancé Doricourt, who have been engaged since childhood, but who have not seen each other in years. Doricourt, back from his tour of the continent, has returned to London as its most fashionable and seemingly eligible bachelor. Abroad, he has learned to appreciate continental beauty and manners and he disparages Englishwomen (much to the disgust of his good friend, Saville). Letitia finds herself captivated by the man Doricourt has become, but dashed by his apparent indifference to her. She vows to “win his heart or never be his wife.”

Her stratagem, as she confides to her doting father and her cousin, Mrs. Racket, is based on the maxim that it is “easier to convert a sentiment into its opposite than to transform indifference into tender passion” (p. 227 [1.4.225-26]). Letitia plans to disgust Doricourt by posing as an ignorant, vulgar rustic and later to enchant him in masquerade as a cosmopolitan lady of mystery. In many ways, this plot is a reversal of Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer, in which Kate Hardcastle wins her lover by abasing herself. Kate is building up the confidence of a man too insecure to address women of his own class; Letitia, on the other hand, cuts Doricourt down to size and makes him acknowledge his own naïveté.

Cowley’s secondary story line is a retelling of the Pinchwife plot of Wycherley’s The Country Wife. Sir George Touchwood, a man of the world and former avowed bachelor, has married the lovely but sheltered Lady Frances. He has been compelled to bring her to London to be presented at court, but aspires to keep her all to himself and away from the pernicious pleasures of the town that once made up his own life. While Sir George lacks Pinchwife’s overt cruelty, Cowley uses his character to question whether jealousy and the concomitant infantilization of the beloved is not cruelty in and of itself. Cowley’s character Courtall, a rewrite of Wycherley’s Horner, the man out to seduce the naïve bride, is a rake in the wrong century. His seduction plots backfire and sexual humiliation is his to receive, not to inflict.

Bridging the two stories are Mrs. Racket, a merry widow, and Villers, a debonair bachelor – a witty sophisticated pair who egg on the mischief, and each other – as well as Flutter, a gossipy fop who can be counted on to get every story wrong, and loyal Saville, Doricourt’s best friend, who still pines for Lady Frances.

The major plots of The Belle’s Stratagem can be staged as an effervescent confection – fast-paced, intricately choreographed and filled with sparkling repartée. The transitional scenes ground the plot by revealing the sordid underpinnings of frivolous fashionable life. Cowley gives us our first glimpse of laboring life in the second scene of the comedy, among Doricourt’s servants. A tabloid reporter bribes Doricourt’s porter for information on any romantic liaisons involving his quasi-celebrity master. They dicker over the value of the porter’s possible information. Their tète-á-tète is interrupted by the entrance of a horde of servants and tradesmen, who have bribed Doricourt’s valet for a view of the gentleman’s haute couture Parisian fashions with an eye to copy them for their masters and customers. Later there is a scene between an auctioneer and his shills. These lower-class hirelings pose as people of fashion, bidding on items to help drive up the prices.

Each of these scenes serves as a precursor to the later grand masquerade. Below stairs at Doricourt’s and at the auction house, we see the lower classes masquerading as the elite for various motives. In the first, they are creating a parallel world to those of the upper classes: just as Doricourt is preparing to attend the king’s levée and people of high fashion hang around the court to stay current on the latest gossip and trends, so the servants and the less socially prominent attend the households and servants of the fashionable. At the auction house, the auctioneer, Mr. Silvertongue, prepares his “puffers” to drive up the bids at the upcoming sale. He coaches them on jargon and the details of artists and items and he criticizes their clothing. They must appear like people of fashion to fool people of fashion. A female puffer complains Silvertongue doesn’t pay her enough to afford appropriate clothes and they argue about wages, comparing them to soldier’s wages. The behind-the-scenes scrapping reminds the audience that London’s fashionable life is based on a teetering economy: everyone at the auction is there to ogle or buy items seized to settle debts of those financially ruined by gambling and extravagance.

These scenes stand out from the general effervescence with their ugly glimpses of the economic realities behind the glamour. They have grit. They rub our noses into the fact that this is a society of many degrees of haves and have-nots. And some of these have-nots are finding and taking every opportunity to exploit their oblivious masters. They call our attention to the cannibalistic nature of this society, as we watch different classes prey upon each other and even on the remains of members of their own class who have fallen into financial ruin.

These transitional scenes present us with dramaturgical choices: how much attention should they be given in comparison to the scenes of the major action? Are they casual moments the audience catches in passing, or are they moments that deliberately stop the forward motion of the plot? How much do they infiltrate or color our perception of the fashionable society that dominates the plot? In some productions, historically as well as today, they are cut entirely.

There is no right or wrong answer, but whatever choice we make will color the audience’s understanding of the text. We can compare a dramatic work to a diamond: letting different facets catch the light changes our view of the stone itself – its color, its reflective capacities, even its beauty. In teaching a play, examining several of the different facets and their coloring of the interpretation of the piece will give students a richer understanding of how a dramatic text comes to life.

Furthermore, to understand the possible choices, we will need to encourage our students to do multidisciplinary research. In the case of The Belle’s Stratagem, such research will involve cultural and economic history of the period. What did the people look like? Who are the servants to the upper classes? What are their backgrounds? What was a levée? How is a levée being parodied? What were the gossip columns of the day like? How do they compare to today’s tabloids? What was the role of the auction houses? What was being auctioned? Where and how did classes mix? There are so many topics that could be explored to shed light on the life the play assumes its audience will know that it is impossible for a teacher to cover them all in a class. One possible way to involve students in unearthing the social assumptions of the play would be to have them do individual reports or papers on different topics and then share them with the whole class. Once everyone has a substantial background in the social world of the play, discussions can take place about how to incorporate this new understanding into the staging of the play.

To demonstrate how a class might go about this process, I will use the example of one marginal character within Belle’s Stratagem and the questions that are raised by Cowley’s employment of her. Kitty Willis comes to play an important role in one of Cowley’s major plots, although Kitty has very few lines. Courtall, the supposed rake, has taunted Saville, Doricourt’s best friend, over Saville’s chaste passion for Lady Frances Touchwood. Saville insults Courtall by casting doubts on Courtall’s self-proclaimed successes with women. An enraged Courtall plots his revenge by planning to deceive and abduct Lady Frances at the masquerade, but Saville gets wind of the plan and decides to outplot the plotter. Saville confides in Doricourt that he has found a woman “whose reputation cannot be hurt” (p. 256, [4.1.155]) to masquerade as Lady Frances and deceive Courtall. That woman is Kitty Willis. This is the only description we are given of Kitty. As Shakespeare would say, “The rest is silence.” (Hamlet, 5.2.360) But for drama to live, the silence has to be filled. How do we discover how to fill it?

Staging the Prostitute

‘

—Uta Hagen, Respect for Acting

—Constantin Stanislavski, Creating a Role

To understand how to teach our students how to approach the dramatic text as the framework for a performance, I suggest starting with the language of theater practitioners. One of the first tasks a director, actor, designer, or dramaturg undertakes when beginning to work with a script is to to determine the “given circumstances” of the text or of an individual character. These “given circumstances” are the facts the author has provided for us through the words and actions of the play. They are the theater artist’s point of departure in analyzing the text, and they will vary depending on whether one is examining one specific character or the entire play. One character’s given circumstances will differ from another’s by virtue of what the character knows about the rest of the plot or characters, as well as who the character is. Differences about what each character knows are often the basis of comedy and farce. Differences about who characters are provide depth and variety to the life of the play.

What are Kitty Willis’s given circumstances? Cowley provides us with minimal information. Kitty:

- has a distinctive, diminutive name.

- is a woman whose reputation cannot be hurt.

- doesn’t believe many women can sustain a character of virtue throughout a masquerade.

- is not believed by Saville to know much about women of virtue.

- is in the plot for reward.

- is able to deceive Courtall into believing she is Lady Frances.

- is immediately recognized by all the men when she unmasks in Courtall’s rooms.

- is addressed merely as “Kitty” by the men.

- teases Courtall about his former adoration of her.

From these given circumstances, we must make deductions and begin our research.

Kitty appears to be a publicly known woman whose reputation seems to be beyond being able to be damaged, written by a publicly known woman who was always having to defend her respectability from damage. (By 1780 women novelists could be respectable, while actresses were still considered not much better than prostitutes. As a playwright, Cowley found herself in disputed territory: did the public confer upon her the respectability of the novelist or the opprobrium of the actress/prostitute? Although she asserted her respectability – even when writing the words of disreputable characters – critics challenged “whether Mrs. Cowley ought so to have expressed herself?”)

Kitty’s very name suggests animality, sexuality and lack of will. Her circumstances suggest that she is some kind of prostitute, courtesan, or actress, but what kind? Research into the topic of eighteenth-century British prostitution yields many different possible answers to this question, each of which provides us with different approaches to staging Kitty. Any production must make one strong choice about Kitty and allow that choice to influence the staging of her relationships with each of the characters she encounters, including the effect her presence brings to the central masquerade scene.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, prostitution was the subject of much public debate and fascination. It not only played a part in many of the novels of the day, but prostitute narratives, purported to be the true histories or memoirs of real prostitutes and courtesans, proliferated and were vastly popular. In her recent study, Infamous Commerce: Prostitution in Eighteenth-Century British Literature and Culture, Laura Rosenthal points out that these novels and narratives took primarily two different approaches to the profession. The first took the form of libertine narrative in which a woman rises through her labors to fame (or infamy) and fortune. There is a quality of entrepreneurship to her profession and ownership of her body. Such narratives describe a woman rising from the brothel to the life of celebrity as a courtesan; sometimes they show her fall back into degradation and poverty, but still she remains a sympathetic representative of upward mobility, using what she has to succeed.

The second type of prostitution narrative shows the prostitute as tragic victim. She is driven by economic necessity to degradation and her feelings are sentimentalized. As one such writer describes, ‘There are not perhaps on Earth greater Objects of Compassion; all Sense of Pleasure are lost to them, the whole is mere Labour and Wretchedness, they are Slaves to, and buffeted by every drunken Ruffian, they are the Tools of, and tryrannized over by the Imps of Bawds.

’ This sentimental view was pervasive in the mid-eighteenth century, as is evident in the wide public support given to the founding, in 1758, of the famous London Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes, dedicated to restoring these victimized women to their natural virtue.

That two seemingly disparate views of prostitution could be held synchronously reflected the ambivalence with which the British viewed the institution. Contemporary travel writer J. W. Archeholz commented in his A Picture of England: Containing a Description of the Laws, Customs, and Manners, that the British had no real stake in ending prostitution. While English laws “are not favourable to the fair sex,” successful prostitutes enjoy independence and add glamour to London.

While social reformers might call attention to the degraded streetwalker, abandoned by her family to the horrors of poverty and violence, the courtesans of the day were the objects of insatiable voyeurism, much like celebrities in our tabloids today. Hogarth painted the former in his scenes of London life; Reynolds glorified the latter.

In fact Sir Joshua Reynolds painted several magnificent portraits of Kitty Fisher (d. 1767), who may have been the namesake of Kitty Willis. Kitty Fisher was one of the most famous courtesans of the 1760’s and a great favorite of Reynolds.

Fig. 1 Reynolds, Joshua. Kitty Fisher as Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl (1759), “Painted Ladies,” Reynold: Joshua Reynolds and The Creation of Celebrity. Tate Online. http://www.tate.org.uk/britain/exhibitions/reynolds/roomguide7.shtm

Nathaniel Hone also painted her in 1765 in a portrait which made a visual pun on her name. In Hone’s portrait of Kitty Fisher, he seats her next to a kitten trying to fish a goldfish out of its bowl. Kitty had begun her career as an actress, but found more lucrative work and celebrity as a courtesan. Her narrative reflects the typical view of both reformers and libertine writers that some young women believed their beauty and accomplishments made them eligible to rise socially and turned to prostitution as a business to make the most of their talents. Kitty Fisher was one of those who succeeded.

Hogarth, on the other hand, portrayed The Harlot’s Progress in a series of paintings dating from 1732 in which the painter satirizes London corruption by tracing the history of a young country girl who is accosted by a bawd upon her arrival in London to seek work. She rises as high as a kept mistress, but then is reduced to a common prostitute, an inmate in debtor’s prison, and finally she dies of venereal disease. Such a degraded woman is also described by The Spectator: ‘I could observe as exact Features as I had ever seen, the most agreeable Shape, the finest Neck and Bosom, in a Word, the whole Person of a Woman exquisitely beautiful. She affected to allure me with a forced Wantonness in her Look and Air; but I saw it checked with Hunger and Cold: Her eyes were wan and eager, her Dress thin and Tawdry, her Mein genteel and childish. This strange Figure gave me much Anguish of Heart, and to avoid being seen with her I went away, but could nor forbear giving her a Crown. The poor thing sighed, curtsied, and with a Blessing, expressed with the utmost Vehemence, turned from me.

Fig. 2 Hogarth, William. Harlot’s Progress: Scene in Bridewell, 1732. British Museum, The Image Gallery, Data from University of California, San Diego.

Even some of the libertine narratives show how the most successful and celebrated courtesan can be vulnerable to a fall into want, degradation, and decrepitude. “Simon Trusty” wrote a public letter to Kitty Fisher herself to warn her of such a possibility:

You, Madam, are become the Favourite of the Public and the Darling of the Age…Your Lovers are the Great Ones of the Earth, and your Admirers among the Mighty: they never approach you but, like Jove, in a Shower of Gold….

Say, Madam, for surely Experience inables [sic] you to do it, what Satisfaction there is in receiving to your Arms one you secretly loathe; the very Reflection makes you sigh: You press him to a joyless Bosom; the Night is tedious and irksome; the Morning comes to your Deliverance, and finds you dejected, and that Eye which should be filled with Joy, ready to start with a Tear….

Tell me then, in the Name of Beauty tell me! Was that fair Form made for Pollution, for the ruffian Embrace of the Great Vulgar, and, ’ere long, perhaps, of the Small? To be for a While what Shakespeare calls‘The cull’d Darling of the World,’

And, at last, the hackneyed Prostitute of every Passenger?

Simon Trusty. An odd letter, on a most interesting subject, to Miss K---- F--h--r. Recommended to the perusal of the ladies of Great Britain. By Simon Trusty, Esq. (London, 1760), Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Gale Group, http://galenet.galegroup.com/servlet/ECCO . Gale Document Number: CW3305850508

So into which of these categories will we place Kitty Willis? Is she a well-known courtesan? A former courtesan or kept woman, known to all the men as last season’s fashionable face, but now down on her luck? Is she destitute and desperate? Or is she an actress? And once we have decided what kind of public woman she is, how will we stage her and how will she fit into the ensemble of other characters?

As is typical of many skilled dramatists, Cowley provides us with information that can be interpreted in a number of ways. On the one hand, Kitty’s name recalls the late famous Kitty Fisher, but on the other hand, another famed “Kitty” was the great actress Kitty Clive (1711-85). Both Kitty Fisher and Kitty Clive were well-known celebrities and women of wit, intelligence and ambition, but Cowley’s Kitty is “Willis” or perhaps, “will-less,” that is without inner strength or ambition, a woman who has simply “fallen” into her line of work because of her lack of discipline or fortitude. Cowley even makes a subtle allusion to the desperation of this latter kind of prostitute when she has the fop Flutter entertain Lady Frances with the description of a family at the masquerade: ‘In the next apartment there’s a whole family, who, to my knowledge, have lived on watercresses this month to make a figure here tonight; but, to make up for that, they’ll cram their pockets with cold ducks and chickens for a carnival tomorrow. (4.1.82-86)’ Cowley here alludes to Henry Fielding’s poetic description in his The Masquerade:

Below stairs hungry whores are pickingThe bones of wild-fowl and of chicken;And into pockets some conveyProvisions for another day.

Henry Fielding, The Masquerade (London, 1728. Reprinted in Henry Fielding, The Female Husband and Other Writings, ed. Claude E. Jones, English Reprint Series, 1960), p. 32 (lines 191-94).

Might Kitty be a desperate woman eager to take this job for the free food at the masquerade, like the provident family and hungry whores, in addition to her pay for the deception at Courtall’s?

And how precisely do the men “know” Kitty? They are all on familiar enough terms with her to address her simply as “Kitty,” when they discover her in Courtall’s rooms, while they address none of the women of their own class so informally. Is she communal property? As a whore or as a celebrity? Is there anything particular about her relationship with Courtall that might add to her enjoyment of the joke?

Again, I reiterate, there is no one right answer to this question, only choices – although some choices are more interesting than others. These are more places where Cowley is silent and where the script must be fleshed out. This is where actors and directors ask, “What if?” What if Courtall was Kitty’s original seducer? Or what if he had formerly kept her? How would such possibilities contribute to deepening Courtall’s sense of humiliation in mistaking Kitty for Lady Frances when he has her in his bedroom? What would such an interpretation add to the significance of Kitty’s line to Courtall after he has damned those present for humiliating him, “What! Me, too, Mr. Courtall? Me, whom you have knelt to, prayed to, and adored?” (4.2.61-62). Is Kitty just adding to the banter or is she getting her own revenge?

Applying Dramaturgical Theory

When staging a performance of Belle’s Stratagem, one has to make one choice and commit to it. All further choices build upon those that have gone before. How should Kitty be costumed? If she is wearing a domino, as Cowley describes, do we see her own clothes under it when she unmasks? If so, will they be the equivalent of the society women’s we have seen. More ornate? Will they be shabby or dirty? Who is revealed when Kitty unmasks? A proud woman of the world or one closer to the prostitute described by the uncomfortable Spectator on an evening in the early part of the century? Kitty’s unmasking prefigures Letitia’s unmasking at the conclusion of the play. How do they connect to each other?

Fig. 3 Cooper, David, photographer. Kitty Willis (Aisha Kabia) taunts Courtall (Mirron E. Willis), The Belle’s Stratagem, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, 2005.

Understanding who prostitutes were in the London of the late eighteenth century as well as understanding who the women of high society were and what was expected of them, gives students a grasp of the visceral reaction an audience would have to seeing both respectable and disreputable women in the same public place or confusing them. It calls their attention to questions the play is raising about how women are categorized and about the fluidity of anyone’s identity. When Cowley dresses Sir George, Lady Frances, Courtall, and Kitty in interchangeable costumes, she suggests with the different pairings that result in the course of the ball, the ease with which the rake can be confused with the devoted husband and the harlot with the virtuous wife. Does Kitty becomes Leah to Lady Frances’s Rachel, sisters under the veil, in some ways indistinguishable? Does Courtall’s inability to distinguish between the masked Kitty Willis and Lady Frances reflect on Doricourt’s inability to distinguish the real Letitia behind her many masks? If so, how?

When teaching the play in class, however, I advocate exploring as many of the choices as time permits. Asking our students to look at a variety of perspectives increases their understanding of a play as a living art. Each choice is an interpretation of the play. How do we come to see how examining a particular facet of a play from a particular angle reflects throughout the whole gem of the play? How do we consciously lead an audience to view a play based on a particular interpretation? For this, I recommend further readings about the art of dramaturgy and ideas and theories about how to connect audiences with classic productions.

One of the best texts for introducing students to dramaturgy as a discipline is Dramaturgy in American Theater: A Source Book, a collection of essays on various aspects and uses of dramaturgical theory and practice. Selected essays from the section entitled “New Contexts” are especially appropriate for teachers and students of Romantic Drama. In her essay, “Aiming the Canon at Now: Strategies for Adaptation,” Susan Jonas examines “how theatermakers can employ the canon to reveal its own biases”

(emphasis hers). One technique Jonas suggests to amplify marginalized voices from an historical text is one she terms “simultaneity” (255). Simultaneity refers to seeing a silenced aspect of the play at the same time as the play proceeds as scripted. Such a technique encourages the audience to view the play from the perspective of the less-privileged characters and thus critically comments on the actions of the central characters and expands our understanding of the world of the play. I will use this technique to suggest one possible way of exploring Belle’s Stratagem dramaturgically.

While there are several scenes of lower-class characters used as transitions in Cowley’s comedy, there are also public scenes for which little description is provided. The play opens with Saville arriving with his servant at Lincoln’s Inn, one of the inns of court where lawyers keep offices. Courtall describes the place as “the most private place in town” (1.1.39-40) of a morning because no fashionable person would be seen there – unless on legal business. But Lincoln’s Inn is inhabited by lawyers, their families, their servants and their clients. People indeed may be coming and going during the scene, just not people of high society. Saville begins the scene at a loss for where to go and is talking with his servant before he sees Courtall. What if before he sees Courtall, the audience sees Courtall being accosted by or in conversation with Kitty – perhaps trying to extricate himself from her; perhaps giving her money? If we have made the choice that Kitty has seen better days, how will this contribute to their later confrontation? There is nothing in the script to prevent such a meeting. Might Courtall be a poseur? Are his vaunted relationships with “women of quality” really only assignations with prostitutes or seductions of young girls? How might such a choice play out over the production? Or is Kitty some relic from his past? Is he in her debt? Does he owe her money? No dialogue needs to be spoken, yet questions can be raised in the audience’s mind.

Other public scenes include the auction and the masquerade. Are there possibilities for simultaneous actions in any of these? Cowley provides dialogue for the auctioneer and his puffers before the gentry enter, yet she doesn’t account for the actions of the shills once the fashionable characters arrive. What are they doing? Are they interacting? Pickpocketing? Are they successful in impersonating the visitors? Does Kitty Willis make an appearance? Is she the celebrated, wealthy courtesan, shunned by the women but fawned over by the men? Or is she, like the puffers, trying to appear fashionable, but coming up short? Does she make any connection with Courtall here? If so, what kind? What about the masquerade? What is Kitty’s relationship to Saville? Is he hiring an impoverished whore, a moderately successful one, a kept woman, or a courtesan out for a lark? Do we recognize any of the servants or tradesmen at the masquerade? Is the tabloid writer lurking there (or at the auction, for that matter)? Simultaneous actions fill in the world of the play.

Other possible dramaturgical approaches might be to create framing devices or to utilize Brechtian alienation techniques. In the first transitional scene in the play, Cowley shows us servants and tradespeople actively observing and feeding off the lives of the fashionable. Might these working-class people observe, judge and/or profit from their masters throughout the play? Might they be watching everything from the sidelines or margins? Might we see their reactions to the stratagems and counter-stratagems of those who live the high life? Cowley embeds many metatheatrical elements within the comedy of various characters performing for others. Could we expand on the metatheatrics and create a variation of the Shakespearean conceit of one set of characters watching and reacting to another set performing a play for them? When she is not part of the action, could Kitty be watching and forming her own judgments that color her responses within her scenes?

Might some, or all, of the actors be playing their lines to the audience by calling attention to their own judgment of the characters? This type of approach deliberately distances the audience from the action of the play rather than draws it into a suspension of disbelief. It is part of the technique Bertolt Brecht uses to create what he calls the “alienation effect,” and its purpose is to call attention to the economic, political and class issues inherent in a dramatic text. Brecht does not want the audience to “feel” for the characters so much as to “think” about them and the significance of what they do. Brecht lays forth his theories in The Messingkauf Dialogues.

A useful assignment to help students understand how Brechtian theory can be applied to historical drama, is to have them read and compare John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728) to Brecht’s adaptation of it, The Threepenny Opera (1928). What if the actress playing Kitty plays her as if she is an observer commenting on her character and the actions of the scene in Brechtian fashion?

All of the questions I have suggested derive from the initial question of how to stage the character of Kitty Willis, a character who appears in only two scenes of The Belle’s Stratagem and who only speaks five lines in those scenes, and yet the choices we make about this character color the interpretation of the entire play. Such dramaturgical questions must be asked about every character and every scene in every production of a dramatic text, and so infinite interpretations are possible and valid. Each staging must simply be consistent within itself.

Teaching our students to approach Romantic Drama dramaturgically teaches them to work in a multidisciplinary fashion and create a dynamic relationship with the text. It encourages them to perform primary research into the period and to track down images, music and cultural artifacts of the period, including gossip columns, broadsides, and other records of popular culture. Understanding what connected and still connects an audience to a play helps them to make personal connections as well. Our goal is to help students see Romantic Drama as a multi-faceted art form as alive and open to interpretation today as it was two hundred years ago.

Bibliography/Suggested Reading

- The Spectator Bond, Donald F. (ed.) 1965. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- A Picture of England: Containing a Description of the Laws, Customs, and Manners of England 1789. London: Edward Jeffrey.

- The Messingkauf Dialogues 1965. London: Methuen.

- Masquerade and Civilization: The Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-Century English Culture and Fiction 1986. Stanford: Stanford UP.

- “Dramaturgy, An Overview” pp. 3-15.

- The Belle’s Stratagem Eighteenth-Century Women Dramatists Finberg, Melinda C (ed.) 2001. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Roxana 1964. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Eighteenth-Century Collections Online n.d. . Gale-Cengage Learning. no. CW3305850508.

- The Masquerade 1728. London.

- The Beggar’s Opera Roberts, Edgar V. (ed.) 1969. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P.

- Respect for Acting 1977. New York: Macmillan.

- “Aiming the Canon at Now: Strategies for Adaptation” pp. 244-265.

- Jonas, Susan, Proehl, Geoffrey, Lupu, Michael (eds.) Dramaturgy in American Theater: A Source Book 1997. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace.

- The Female Husband and Other Writings Jones, Claude E (ed.) 1960. Liverpool. English Reprint Series

- Cook, Richard I. (ed.) A Modest Defence of the Public Stews 1724. . 1973. Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library.

- “Rebottling: Dramaturgs, Scholars, Old Plays, and Modern Directors” pp. 292-307.

- “The Magdalen Hospital and the Fortunes of Whiggish Sentimentality in Mid-Eighteenth-Century Britain: 'Well-Grounded' Exemplarity vs. 'Romantic' Exceptionality” The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation Summer 2007. vol. 8 pp. 125-48 no. 2.

- Infamous Commerce: Prostitution in Eighteenth-Century British Literature and Culture 2006. Ithaca: Cornell UP.

- Hamlet The Complete Signet Shakespeare1972. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

- Hapgood, Elizabeth Reynolds (ed.) Creating a Role1961. New York: Theatre Arts Books.

- “No Vice or Wickedness” The Spectator Friday, January 4, 1712. vol. 2 no. 266.

- The Sign of Angellica: Women, Writing and Fiction, 1660-1800 1989. New York: Columbia UP.

- An odd letter, on a most interesting subject, to Miss K---- F--h--r. Recommended to the perusal of the ladies of Great Britain. By Simon Trusty, Esq 1760. London.