“Holy Theatre” is a term known to drama students and theatre practitioners primarily from Peter Brook’s treatment of it in his 1968 classic, The Empty Space. It is, Brook says, “the Theatre of the Invisible – Made – Visible” (42); it is the kind of theatre that arises from a deeply felt urge to “capture in our arts the invisible currents that rule our lives” (45). Christopher Innes, in his study Holy Theatre, observes that its “hallmark” is an “aspiration to transcendence, to the spiritual in its widest sense” (3) and that it attempts to “transcribe subjective experience directly into stage terms” (29). The effect is meant to be communal: a theatre “that brings its spectators into emotional harmony with one another by celebrating their common identity as human beings” (Auslander 13).

Brook took the term “holy” from Antonin Artaud’s vision of theatre as “a metaphysical force,” “holy rite and quasi-religious practice” (Esslin, Antonin Artaud 101). Artaud’s work was in part a return to and a nostalgia for the prehistory of theatre, the ancient cult rituals and goat-songs that developed into Greek drama, and that were celebrated as the “Dionysian” split from “Apollonian” harmony, rationalism, and sculpture in Nietzsche’s highly influential The Birth of Tragedy (1872). This metaphysical or “holy” impulse in theatre has a long history, and can be seen as one of the “master currents” of dramatic literature and theatre theory.

As is well known, the study of European drama has greatly favored the master current that flows toward realism and naturalism, a narrative of progress that celebrates the late nineteenth century arrival of the “well-made play” and the “problem play” (ushered in by the reigning triumvirate of Ibsen, Strindberg, and Chekhov, with the frequent addition of Shaw), dramas that work from the “bottom up,” grounded in the material world and social issues. Plays that endeavor something else, namely to stage subjective states, have been dropped into the valley of the unstageable and unstageworthy. These are the plays of the master current of the holy theatre. They tend to get labeled “closet dramas,” “symbolist,” “impressionist” or “expressionist,” “experimental” or “avant garde.” Philosophical plays concerned with revealing states of mind, consciousness, dreams, ghosts, magic, they work from the “top down” and begin in abstraction, “sojourning through consciousness and affecting the ‘reality’ of the material world beneath it,” as William Demastes explains in Staging Consciousness: Theater and the Materialization of Mind (15). The plays are an exploration of the human condition, but from the “inside out” rather than the social realism approach of “outside in.” (However, plays with the greatest lasting impact tend to be a combination of both these traditions, from Hamlet to Death of a Salesman to Angels in America.)

The dramatists of this lineage (loosely defined) were also deeply invested as theorists of the theatre (or, put differently, this way of seeing theatre attracted theorists who became dramatists to test their theories). We see this pattern very clearly in the emergent Romantic theatre of the eighteenth century in Germany (e.g., in the work of Lessing, Schiller, Tieck, and Kleist) and in early nineteenth-century England in the staged theories of Joanna Baillie and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

In this drama course we examine some of the major dramatic texts that could be said to make up a holy theatre tradition, with Coleridge’s Remorse (1813) and Baillie’s Orra (1812) representing Romantic drama.

Alongside these plays we read theatre theory and study developments in stagecraft that allowed dramatists to explore subjective states onstage. In this context students are encouraged to see Romantic drama as inspired by the vision and techniques learned from Shakespeare’s plays (rather than weak imitations of Shakespeare), as a reworking and transformation of the Gothic, and as the birthplace of the modern avant garde. To many Romanticists this is going to look (suspiciously, perhaps) like the “old” approach to Romantic drama—that is, Romantic drama as “mental theatre,” a label under which it has not tended to fare well in criticism. However, when studied within the lineage of holy theatre, Romantic drama can stand out as a peak—rather than a valley—in the history of dramatic literature and theatre theory.

There are several tributaries of the master current of holy theatre: one focuses on pure form (we see this in the modernist avant garde in particular, e.g., in the theatrical experiments of Gertrude Stein and Wassily Kandinsky), another on myth and ritual (which points up the ancient origins of holy theatre, running from Euripides’s The Bacchae to Peter Shaffer’s Equus). In order to highlight the stream of holy theatre attempting the revelation of consciousness, this version of the course begins with Shakespeare’s “strategic opacity” and Hamlet, the Ur-text of the dramatic representation of consciousness.

To Romantics and their followers, the conditions of the Elizabethan theatre (and the thereby conditioned Elizabethan audiences) were ideal because they drew upon the imagination, truly created a “theatre of the mind.” Those early modern audiences viewed a virtually bare stage with no external lighting (at the outdoor theatres such as the Globe, anyway); the language of the plays frequently remind them to imagine the scene that is being played out before them. Shakespeare’s eighteenth-century admirers developed a new form of literary criticism—“character criticism”—in response to the complexity and seeming humanness of his characters, and gave us the now-familiar figure of the natural genius Shakespeare who had discovered the secret to how to reveal interiority on the stage. A. W. Schlegel’s image from his 1808 lectures is a familiar one: Shakespeare’s characters are like “watches with crystalline plates and cases, which, while they point out the hours as correctly as other watches, enable us at the same time to perceive the inward springs whereby all this is accomplished” (“A Course of Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature” 362). More recently, Stephen Greenblatt has echoed this language in Will in the World when he argues that Shakespeare “perfected the means to represent inwardness” (299) through the innovation of the soliloquy, in particular what Greenblatt refers to as “strategic opacity,” or a new technique of “radical excision” in which Shakespeare took out a “key explanatory element, thereby occluding the rationale, motivation, or ethical principle that accounted for the action that was to unfold” (323-24). Relying on “inner logic” rather than causal events, Shakespeare “fashioned an inner structure through the resonant echoing of key terms, the subtle development of images, the brilliant orchestration of scenes, the complex unfolding of ideas, the intertwining of parallel plots, the uncovering of psychological obsession” (324). Greenblatt’s Shakespeare is remarkably Romantic, and effectively introduces holy theatre dramaturgy; strategic opacity was “not only a new aesthetic strategy,” but “expressed Shakespeare’s root perception of existence, his understanding of what could be said and what should remain unspoken, his preference for things untidy, damaged, and unresolved over things neatly arranged, well made, and settled” (324).

Both Hamlet (1600-01) and The Tempest (1610-11) exhibit the Renaissance view of the world as a stage and faith in theatre as a means of revealing truth. Thanks in large part to Romantic writers and critics—Goethe, Lamb, Hazlitt, Coleridge—Hamlet has come to be considered a play about consciousness, and Hamlet the “prince of the inward insurrection” (Greenblatt 303). When read as a foundational text of holy theatre, what comes into focus are Hamlet's conversation with the Ghost and the unfolding of Hamlet’s consciousness through the soliloquies, tracing the fluctuations of his mind from his first appearance to Act V. The course then moves to The Tempest, which, among its dominant interpretations, can be seen as a play about the magical power of theatre to bring about reconciliation and forgiveness. It also provides an excellent entrance into Coleridge’s Remorse, as both plays use an act of magic, of dramatic illusion, to prick the conscience of and draw remorse from a wayward brother.

Baillie’s Orra (1812) is chronologically prior to Remorse (1813), but teaching it afterward allows the course to move immediately into Strindberg’s The Ghost Sonata, which is similarly “hauntological” and includes an apparition as well as “living ghosts,” characters who are, like Orra in the final scene of the play, psychologically haunted and poised between death and life. Moreover, Strindberg’s desire for an intimate performance space that could capture the nuances of his plays—which resulted in the founding of the Intimate Theater in Stockholm in 1907—carries startling echoes of Baillie’s “…

Teaching Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Remorse

The main plotline of Remorse echoes themes in The Tempest; in both, an ambitious and rebellious younger brother (Antonio in The Tempest, Ordonio in Remorse) plots to kill a virtuous older brother (Prospero, Alvar) and sends that virtuous brother into exile. (The differences can be illuminating to discuss. Prospero can set up circumstances to awaken Antonio to his wrongdoing, but cannot ultimately transform Antonio’s inner self; while Prospero expresses forgiveness in the end, Antonio does not appear to express remorse.) In Remorse, while Alvar is gone (Ordonio had arranged to have him killed, and assumes him dead), Ordonio tries to win over Alvar’s beloved, Teresa. She wants nothing to do with Ordonio, and, anyway, is waiting with hope for Alvar’s eventual return, since his body has never turned up. Ordonio designs a spectacular illusion to convince Teresa of Alvar’s death: a glowing altar which will summon the image of the dead Alvar. Unbeknownst to all (except the audience), Alvar is not dead; he had escaped the assassin and has returned with a plot to awaken Ordonio to his evil deeds. Notably, this plan is not to seek revenge on Ordonio, but to bring him to remorse. Alvar manipulates the altar trick, making it boomerang on Ordonio: the altar bursts into flames to reveal a picture of the assassination attempt on Alvar, masterminded by Ordonio. Thus Ordonio realizes (1) Alvar is still alive, and (2) he knows about the plot to kill him.

Remorse (1813) is a reworking of an earlier revolution-oriented play entitled Osorio (1797) into a deeper, more psychological study of consciousness: the revision of title alone gives us a clue. In Remorse Coleridge is staging a shift in consciousness, which brings about a change in conscience.

In the Table Talk jottings, Coleridge expressed a special fondness for Remorse: “the ‘Remorse’ is certainly a great favourite of mine,” he stated, “the more so as certain pet abstract notions of mine are therein expounded” (II: 360). Exactly what those pet abstract notions were was never explicitly stated, but reading Remorse within the communality that is characteristic of holy theatre illuminates the play as a tragedy intended to wake not just the character Ordonio but the audience from their dogmatic slumbers or wrongdoings and force them to confront the Otherness that exists inside as well as outside themselves. As has been discussed in a number of studies,

in order to present this concept effectively, Coleridge drew upon the spectacular stagecraft of the popular Gothic drama, which contradicts his theoretical writing, where he finds the Gothic weak and even dangerous.

As a companion text, students can read “Letter II” of “Satyrane’s Letters”—included in Chapter XXII of the 1816 Biographia Literaria but written in 1798—where Coleridge as much as accuses the Gothic theatre of inciting terror. He found the self-reflection of Gothic drama dangerous on at least two counts. The Gothic drama had a tendency merely to reflect, rather than to challenge, the selves of the audience; the values often reflected an easy morality that kept the audiences complacent and inert. Also a dangerous aspect of facile self-reflection, and a more tempting one for Coleridge and others, was, as Jeffrey Cox notes in his discussion of North's The Kentish Barons, that the emotions can be “more deeply rooted by reflection,” a feature much glamourized in Gothic hero/villains. One ideally wants neither passive reflection nor the dangerous inward turn to self-consciousness, both of which can result in fixation and a resistance to change, but instead a self-consciousness which has its ultimate origin in a moral relation to others and which develops dialectically in continual relation to others. One way to break out of a potentially solipsistic cycle is to engage with others, and for a writer, the stage is therefore an ideal medium. Coleridge was frustrated with the limitations of the commercial stage of his day, but he knew that that was the means through which to present such ideas visibly and publicly, and to reach the widest audience for his ideas. As William Galperin points out in The Return of the Visible in British Romanticism, issues of the visible continually verge upon issues involving community (164) and, though Coleridge in his criticism may have occasionally demonstrated an anti-theatrical bias, he reached for the visible to present the transformation of a consciousness to and for a community. In Remorse he adapted the Gothic formula to his own purpose, and used the Gothic spectacle to affect his audiences, as he advises in “Satyrane’s Letters,” “in union with the activity both of [their] understanding and imagination” (XXII:437).

The Drury Lane playbill for Remorse advertises all new sets, which, according to the dictates of the stage directions, included “wild and mountainous” country scenery and a desolate cavern dripping with water; the setting is the Spanish Inquisition, a remote and terror-ridden time. Coleridge commissioned a score from Michael Kelly, who had composed the music for the most successful of all Gothic dramas, Matthew Lewis’s The Castle Spectre (1797). As Paula Backscheider has noted, “Gothic drama used music in sophisticated ways to engage the senses while subliminally both exercising and containing anxieties” (173); it was as crucial to the play as scores are to film and, increasingly, theatre today. The dramatic structure of the play, however, is focused on Ordonio's consciousness. Coleridge wastes no time getting to his purpose; very little exposition is given before Alvar declares that he has returned to confront his brother and “rouse within him / REMORSE!” in order to “save him from himself” (I.i.18-19). Preparations begin at once for the visible spectacle which will force upon Ordonio a cathartic experience, described by Alvar as “the punishment that cleanses hearts” (I.ii.319)—remorse, rather than revenge. This experience is designed to raise Ordonio's self-consciousness which will in turn prick his conscience and force him to face his transgressions. The visual elements are crucial: Alvar queries his servant Zulimez concerning what they need, “Above all, the picture / Of the assassination—.” “—Be assured / That it remains uninjured, Zulimez answers him (I.i.92-4). The spectacle will work in such a way, Alvar discloses when alone, that “That worst bad man shall find / A picture, which will wake the hell within him, / And rouse a fiery whirlwind in his conscience” (II.ii.172-74).

In order to understand how Gothic techniques can work to present onstage the awakening of a consciousness—and, perhaps, to model a transformation of consciousness in the audience—try staging the key scene of the play in your classroom. This is the moment of the climactic trick that boomerangs on Ordonio, the overwhelming spectacle that results in the first awakening of his conscience.

This spectacle is the showpiece of the evening. It was well-advertised, and no theatrical elements were spared. Thomas Barnes’s review of the play (included in the Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama) provides an eyewitness description: “the altar flaming in the distance, the solemn invocation, the pealing music of the mystic song, altogether produced a combination so awful, as nearly to overpower reality, and make one half believe the enchantment which delighted our senses” (392). Barnes’s choice of words—“mystic,” “awful,” “overpower reality,” and “half believe the enchantment”—are all central to the desired effect of the holy theatre.

EXERCISE 1: STAGING THE AWAKENING OF CONSCIOUSNESS

In this exercise students will perform Act III, scene I of Remorse, recreating the Gothic setting for the “altar scene” in order to understand how the stagecraft works to convey an experience of an awakening of consciousness. You will need at least six actors to play Alvar, Ordonio, Teresa, Valdez, Monviedro, and a few “familiars of the Inquisition” who act but don’t have speaking parts. Others can create music “expressive of the movements and images” of the scene, play it according to the stage directions, and sing the Chorus parts. A third crew can construct the altar spectacle.

- From the text, gather information about the stage setting and recreate this in your classroom. For instance, Coleridge's stage directions call for “a Hall of Armory, with an Altar at the back of the Stage” and “soft music from an instrument of Glass or Steel.”

- Onstage enter Alvar (dressed in a Sorcerer’s robe; the others don’t recognize him), Ordonio, Teresa, and Valdez (father of the brothers Ordonio and Alvar).

- The music should score their dialogue and action. Beginning at about III.i.62, a “voice behind the scenes sings ‘Hear, sweet spirit’” during (the disguised) Alvar’s incantation to raise up the soul of Alvar.

- The goal of the altar spectacle is to awaken Ordonio’s consciousness, so the actor playing Ordonio needs to convey a change over the course of the scene. In the early stages of Alvar’s presentation, for instance, Ordonio still thinks that he is controlling the action, and comments that it would be a joy to see Alvar again. Alvar then begins to unleash upon him a verbal barrage and throughout the scene addresses his lines “still to Ordonio,” heedless of Valdez's interruptions, protesting this assault, which culminates with the stinging “it gives fierce merriment to the damned, / To see these proud men, that loath mankind, / At every stir and buzz of coward conscience, / Trick, cant, and lie, most whining hypocrites!” Alvar then turns away, shooing him “Away, away!” Then, like a director perfectly timing his dramatic effects, he orders, “Now let me hear more music" (III.i.110-14).

- Music cue: the stage directions read “The whole Music clashes into a Chorus.” The Chorus chants “Wandering Demons! Hear the spell! / Lest a Blacker charm compel—”

- Recreate the spectacle of the portrait: the stage directions indicate that “the incense on the altar takes fire suddenly, and an illuminated picture of Alvar's assassination is discovered, and having remained a few seconds is then hidden by ascending flames.”

- Ordonio “start[s] in great agitation” and tries to blame the situation on “the traitor Isidore.”

- Monviedro and the familiars of the Inquisition enter and seize Alvar.

- Ordonio “recovers himself as from stupor” and orders that they take Alvar to the dungeon.

CLASS DISCUSSION

Reflect on how the class’s performance affected you as an actor, designer, and/or spectator. How did the Gothic elements, particularly the music and the altar spectacle, highlight the emotional relationships between the characters and the theme of awakening remorse?

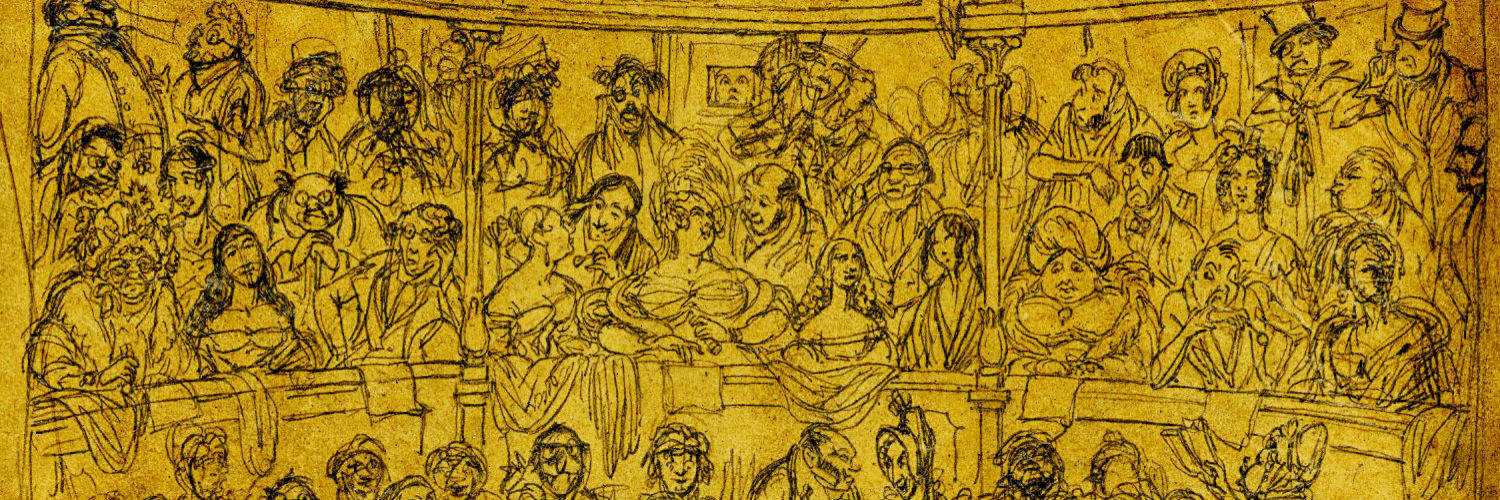

It is likely that the Gothic elements felt awkwardly phony, even laughable, to you. Imagine the original performance circumstances: you are watching Remorse in the 3,000-plus seat theatre at Drury Lane. You go to the theatre eager for spectacle, delighted with and amazed by the technological developments in theatre and the effects they have on you as they lure you into a belief in their reality. (To imagine this, fast forward to the spectacular theatre of today, such as The Lion King, Phantom of the Opera, or Miss Saigon.) How do you think you would have reacted in those circumstances?

Teaching Joanna Baillie’s Orra

Shelley’s sonnet “Lift not the painted veil” (1818) provides an effective lead-in to this reading of Orra because holy theatre, like Orra herself, seeks to lift the painted veil, with often (and necessarily) painful—or, as Artaud later famously phrased it, cruel—results. Baillie’s tragedy on fear in the Plays on the Passions, Orra’s dramaturgical concept is to show the progression of fear in Orra, which starts in a somewhat playful fashion with the enjoyment of ghost stories, and ends in a terrible madness; this aspect of the play takes precedence over the plotline about Orra’s resistance to a forced courtship. Orra shows Orra’s internal state; the audience doesn’t physically see any ghosts, but instead watches the actor playing Orra unveil her hauntedness, or, in other words, react to fear.

Julie Carlson’s essay “Baillie’s Orra: Shrinking in Fear” (included in the recent collection Joanna Baillie, Romantic Dramatist) works well as a contemporary supplement to the play. Carlson proposes the idea that “hauntology” rather than ontology describes our current being and time, and writes that Orra is a haunted and haunting play; it is the exception rather than the rule in the Plays on the Passions and undermines Baillie’s usual emphasis on rational morality. Orra herself is a “spectral subject” in the play (216), a position between the “twos” of binaries (much like Baillie’s own unusual situation in Romanticism and theatre history—not yet acknowledged as a truly “major” figure, yet too major to be “minor”).

Like Remorse, Orra draws upon the conventions of the Gothic and of Romantic medievalism, and similarly, the spectacle is utilized, Carlson argues, as a way of transporting us to a psychic space of sensory perceptions—a “before-human” state that precedes meaning-making (217)—a technique used in Artaud’s twentieth-century performance events that gave audiences a “sensory overload” to break down their habitual rational responses. Gothic spectacle provided “a way of exploring the psychological even before twentieth-century constructions of it,” and “becomes linked to the internal state of the characters’ minds as authors explore how individuals react in times of great stress,” Christine Colón explains (xxiii). Furthermore, since the Gothic “compels an audience to derive pleasure from fear,” it “clearly allies itself with the idea of the sublime”; and “for a playwright like Baillie who desperately wishes to stir her audience members’ imaginations and compel them to transform their lives, the spectacle of the Gothic sublime would have been appealing. It had the potential to awaken audiences and cause them to act” (Colón xxii-xxiii).

In addition, Baillie’s “Introductory Discourse” and note “To the Reader” to the Plays on the Passions should be taught alongside Orra.

(Both are excerpted in The Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama.) As do the other dramatist-theorists in the holy theatre tradition, Baillie is writing a manifesto: creating drama for a theatre that could be—that is, the theatre she wants rather than the theatre she has. It is in the “Introductory Discourse” that Baillie develops the idea for which she’s become best known, that of “sympathetic curiosity.” She does not just make the point that we are curious about other humans, especially when they are experiencing emotional trauma, but that we want to fix our eyes on the manifestation of such trauma on their bodies and faces—to observe their symptoms, as it were. To take just one example that works well with teaching Orra, Baillie writes that one of the things humans are most curious about, yet most scared of, are ghosts. “No man wishes to see the Ghost himself, which would certainly procure him the best information on the subject, but every man wishes to see one who believes that he sees it, in all the agitation and wildness of that species of terror” (359). In other words, we are more interested in reactions to ghosts, in witnessing the experience of having seen a ghost, than in the ghosts themselves. We are aware that it is rude to stare at people, yet we have an overwhelming urge to watch people in distress: “how sensible are we of this strong propensity within us, when we behold any person under the pressure of great and uncommon calamity!” Out of courtesy we will turn our eyes away, yet “the first glance we direct to him will involuntarily be one of the keenest observation, how hastily soever it may be checked; and often will a returning look of enquiry mix itself by stealth with our sympathy and reserve” (359). In short, we enjoy staring at others who are experiencing emotional turmoil; while we restrain ourselves, and offer merely expressions of sympathy, we covertly observe in minute detail the features and physicality that indicate the person’s suffering. Such gazes are inappropriate in polite society; however, our sympathetic curiosity is satisfactorily aroused and exercised by attending the theatre. It gives spectators the opportunity to vicariously steal into the closet—and into the mind—of another. For, as Baillie writes, “there is, perhaps, no employment which the human mind will with so much avidity pursue, as the discovery of concealed passion, as the tracing the varieties and progress of a perturbed soul” (360).

The success of Baillie’s designs to allow audiences to trace the varieties and progress of Orra’s perturbed soul depend heavily on the skill and style of the actors, and thus it is no surprise that her script is filled with detailed prescriptions for gesture and movement to convey the internal state of the character. Here, too, she is advocating for a transformed, intimate theatre in opposition to the conventional performance spaces of her day, which were growing ever larger; in “To the Reader” she writes that the “department of acting that will suffer most under these circumstances, is that which particularly regards the gradual unfolding of the passions, and has, perhaps, hitherto been less understood than any other part of the art—I mean Soliloquy” (375). The plays she is creating need actors who can exhibit “the solitary musings of a perturbed mind” with “muttered, imperfect articulation which grows by degrees into words” or “that rapid burst of sounds which often succeeds the slow languid tones of distress” (375). These precisely observed descriptions remind us of what may be most remarked upon about Baillie’s playwriting, in her own day as well as ours: her diagnostically observant eye and analytic, “anatomical” dramaturgy. The reviewer from Edinburgh Magazine writes in 1818 (excerpted in the Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama) that “no one” except Baillie ever thought of giving, in dramatic form, “an anatomical analysis, a philosophical dissection of a passion” (381). Her plays work as a kind of “microscope, by means of which she seems to think that she has brought within the sphere of our vision things too minute for the naked intellectual eye” (381-2). The reviewer thinks this is the “radical defect” of her plays, but today it is considered perhaps her most brilliant endeavor, an innovative theatrical experiment.

The names of Joanna Baillie and Constantin Stanislavski are rarely, if ever, linked, but he too taught a form of anatomical observation, telling his students that, when creating a role, they should first read the text carefully for the “physical truths” about the character. The fame of American Method acting’s “inside out” approach has obscured other ways of building characters and distorted part of Stanislavski’s original teachings; he instructs his actors not to “truncate” the “inner line” of a role and replace it with their own “personal line,” but to begin with the “physical life” of the character, which is tangible. “The spirit cannot but respond to the actions of the body, provided of course that these are genuine, have a purpose, and are productive,” he explains (Creating a Role 149). Put differently, instead of the later Method acting technique of drawing on the actor’s own emotional and sense memory, the actor was to take on the physical stance, gestures, posture that signaled the emotional feeling of the character. By putting oneself into the physical position, the emotion would follow.

In the eighteenth century, the use of ritualized gestures and poses to convey specific states of emotion had been made popular, codified in acting manuals that illustrated the proper appearance of the gesture or pose and explained what each indicated. (This often seems oddly nonrealistic to us. Similarly, in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century avant garde theatre, actors would strike archetypal poses, rather than move and pause in the realistic manner that’s familiar to us now; these poses were meant to convey certain emotional effects, indeed to heighten the emotional effect altogether.)

The unveiling or revelation of a character’s internal state was a primary feature of late eighteenth-century and Romantic acting theories; the matter of expressing a character’s “passion” is considerably more complicated than having the actors constantly emoting onstage, which would eventually result in a flattened-out performance and not move the audience. To express internal states convincingly, performers developed a number of techniques that included drawing upon their own memories, thoughts, and emotions and transferring them to the character; focusing on communicating explicitly the specific shifts of feeling of thought that a character experiences from one moment to the next; and cultivating an attitude of sympathy among the triangle of character, performer, and viewer by finding the vulnerability of the character and inviting the audience to experience it. As we see featured in Orra, one way an actor would reveal the interiority of a character was by focusing on the way the character reacted to the dramatic situation. As Jonathan Bate has written, the popular view among Romantic theatre artists was that “the essence of human nature is to be found in reaction, not action, and so it was that their performances were most intense at certain moments of reflection” (“The Romantic Stage” 97).

Baillie’s detailed descriptions of Orra’s physical actions and gestures, particularly in her mad scene, instruct the actor on how to accurately depict the progression of her fear. To see how Baillie’s stage directions “direct” the play and help her actors create their roles through anatomical analysis, and to experience how physical gestures can work to help performers feel for themselves and reveal to spectators the characters' emotions, try the following exercise.

EXERCISE 2: PHYSICALLY CREATING THE INTERIOR STATE OF MADNESS

In this exercise students can test Baillie’s instructions to the actor playing Orra in the key scene where she finally goes mad from fear (IV.iii). To play the entire scene you will need actors for Orra, Rudigere, Cathrina, Theobald, and Franko. You could also choose to play just Orra’s soliloquies (IV.iii.27-52 and IV.iii.147-165), as these are the moments for which Baillie provides most specific direction.

- Make a list of all the stage directions that describe Orra’s actions (or reactions) in the scene. (For instance, “pacing to and fro,” “stands fixed with her arms crossed on her breast,” “striking the floor with her hands,” etc.)

- To experience the physical life of the character and the “arc” or progression of Orra’s madness, practice enacting all of the stage directions, the gestures and postures, without saying the lines of the scene. You might treat this as a kind of dance, repeating the series of gestures and movements until you begin to feel the emotional life of the character.

- Then go back and play the scene in its entirety, following the directions as you deliver the lines.

- Everyone should have a chance both to enact Orra’s gestures and to watch others doing so.

CLASS DISCUSSION

What did performing the gestures and actions feel like? Did you ever feel fear rising in yourself simply from doing the physical gestures associated with a person feeling fear? If so, when in particular did you feel it? Of Baillie’s descriptions of a person becoming overwhelmed with fear, in what ways were they accurate and in what ways merely literary?

How did others look when they played Orra? Which gestures or postures most effectively conveyed fear? Which looked most outdated or stagy?

The final scene of Orra makes a nice pairing with Strindberg's The Ghost Sonata (1907). Orra returns to the stage, completely mad, and tells her guardian Hughobert, upon hearing the news that his son died, that “the damn’d and holy / The living and the dead, together are / In horrid neighbourship. – ‘Tis but thin vapour, / Floating around thee, makes the wav’ring bound” (V.ii.208-12). The Ghost Sonata also takes up the notion that the living and dead are in “horrid neighbourship” together, with only the finest boundary between them, although it does so to more psychological ends. In the second act’s famous “ghost supper,” the characters “look like ghosts” and have been drinking tea together for twenty years, “always the same people, saying the same things, or else too ashamed to say anything” (279). “God, if only we could die! If only we could die!” the character named the Mummy cries (283). Remorse can be reintroduced at this point because it also pairs well with The Ghost Sonata when the characters seek to make Jacob Hummel (“Old Man” in the dramatis personae) awaken to his past evil actions and feel remorse for them. Like Remorse and Orra, The Ghost Sonata is rather Gothic and could profitably be brought into a discussion of distinctions between “Gothic,” “Romantic,” “symbolist,” and “expressionist,” for the same elements of stagecraft are alternately labeled “Gothic” when describing Remorse, Orra, and many other Romantic dramas and are thus often considered “low,” pandering to the masses’ love of being surprised with special effects; or they are labeled “Romantic,” “experimental,” or “avant garde,” and then considered “high art.”

Romantic drama as the birthplace of the modern avant garde

When works of the modern avant garde are studied immediately after Remorse and Orra, the kinship with Romantic drama becomes clear in both the shared vision of theatre and the stagecraft employed to realize it. As Peter Brook explains, the holy theatre does not only present the invisible in drama, it “also offers conditions that make its perception possible” (56), such as theatrical spectacle, lighting, a use of ritualistic devices, dance and movement, musical scores and other kinds of sound, and even, in some cases, smell.

Far from being “mere” spectacle or surface—an entertaining painted veil—these elements, whether labeled Gothic, Romantic, or Holy, are employed to lift or transcend reality. Paula Backscheider writes in Spectacular Politics, in a discussion of The Castle Spectre, that Gothic playwrights who added the word “romance” to their titles “signaled their freedom from the referential, veridical world of realist texts and allied themselves with a highly symbolic art, often reaching for a higher reality or a deeper psychology” (156). Theorists of the Gothic, Backscheider continues, have argued that the form “is best distinguished by the experience its readers or spectators have, and it is now widely accepted as an expression of dissatisfaction with the possibilities of conventional literary realism” (156). This dissatisfaction leads to the modern avant garde tendency to elevate mood over plot, or internal over external states, presaged by Baillie’s work in particular.

The twentieth century part of the course looks at Strindberg’s A Dream Play (1901); one-act experiments Interior (1891) by Maurice Maeterlinck, The Wayfarer (1910) by Valery Briusov, and Wassily Kandinsky’s The Yellow Sound (1909); Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953), the text seen by Peter Brook as the apotheosis of holy theatre; Sam Shepard’s Suicide in B Flat (1976) and the off-off Broadway movement; Amiri Baraka’s Artaudian “historical pageant” Slave Ship (1967) and Ntozake Shange’s “choreopoem” for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf (1975); and ends with consideration of the career of Sarah Kane, particularly her plays Blasted (1995) and 4:48 Psychosis (2000). We also discuss the influence of director-theorists Antonin Artaud (The Theatre and Its Double [1938])

and Jerzy Grotowski (Towards a Poor Theatre [1968]—probably best known to people outside the theatre from Andre Gregory’s descriptions of his participation in Grotowski’s life-changing rituals in the film My Dinner with Andre [1981]), whose methods and experiments are probably what first come to mind when one learns about holy theatre. What often strikes twenty-first-century students about this current of theatre is how raw it seems, how earnest or even naïve in its search for authenticity; there’s an openness and vulnerability that can make contemporary audiences conditioned to irony uncomfortable. Contemporary traces of holy theatre are difficult to find; we see them more in rave music, light shows, art installations, and communal performance events such as Burning Man than in staged drama. Postmodernism so changed the tenor of much of the aesthetic that when consciousness is examined in contemporary performance, the tendency has been toward a deconstruction rather than a search for universals and communality. An important response comes in the form of Jill Dolan’s argument for “reanimating humanism (after we’ve deconstructed the blind, transcendent universalisms it once espoused)” (163) and her conceptualization of “utopian performatives” in Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater (2005).

Film is probably the most engaging and accessible contemporary porthole for entering the realms of the holy theatre tradition. As Bert Cardullo notes of modernist avant-garde plays, Romantic dramas would perhaps have been “better suited to the screen than to the stage, assaulting as they did the theater’s traditional objectivity or exteriority and its bondage to continuous time and space” (3). Film is a medium that has been friendly to experiments with the concerns of holy theatre—consciousness, dream states, alternative realities, magic—as can be seen in the popularity of films about consciousness, such as Richard Linklater’s Waking Life (2001) and the documentary What the Bleep Do We Know? (2004), critical acclaim for Julian Schnabel’s evocation of human consciousness in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), the work of Michel Gondry (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind [2004], The Science of Sleep [2006]), and Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010), to name just a few recent examples. A work like Prometheus Unbound (1820), for example, seems to call out for a film adaptation (although the first known staging, by the Rude Mechanicals theatre company in Austin, Texas, in 1998 would challenge that statement. It was excellent.) While film lacks the communality in liveness called for in holy theatre, it can conjure the images and experience of transcendence that were desired onstage. Students probably bring a curiosity about the philosophical, scientific, and psychological matters explored in these films, which may raise interest in seeing how Romantic drama attempts to explore them, too, with the result that Romantic drama is seen as relevant, even prescient, to our artistic concerns, and as a fertile ground for theatrical experimentation.

Works Cited and Referenced

- The Theatre and Its Double 1958. New York: Grove Press.

- From Acting to Performance: Essays in Modernism and Postmodernism 1997. New York: Routledge.

- Spectacular Politics: Theatrical Power and Mass Culture in Early Modern England 1992. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins UP.

- “'Introductory Discourse' to the Plays on the Passions” pp. 357-370.

- “Orra” pp. 133-164.

- “The Romantic Stage” The Oxford Illustrated History of on Stage Bate, Jonathan, Jackson, Russell (eds.) 1991. Oxford: Oxford UP.

- Brask, Per, Meyer-Dinkgräfe, Daniel (eds.) Performing Consciousness 2010. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- New Readings in Theatre History 2003. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- The Empty Space 1968. New York: Atheneum.

- Closet Stages: Joanna Baillie and the Theater Theory of British Romantic Women Writers 1997. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Illusion and the Drama: Critical Theory of the Enlightenment and Romantic Era 1991. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State UP.

- Cardullo, Bert, Knopf, Robert (eds.) Theater of the Avant-Garde, 1890-1950: A Critical Anthology 2001. New Haven and London: Yale UP.

- “Baillie’s Orra: Shrinking in Fear” pp. 206-20.

- “Remorse” pp. 165-204.

- “Biographia Literaria” Samuel Taylor Coleridge: A Critical Edition of the Major Works Jackson, H. J. (ed.) 1985. Oxford and New York: Oxford UP.

- Cox, Jeffrey N. (ed.) Seven Gothic Dramas 1789-1825 1992. Athens: Ohio UP.

- Cox, Jeffrey N., Gamer, Michael (eds.) The Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama 2003. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press.

- Crochunis, Thomas C. (ed.) Joanna Baillie, Romantic Dramatist 2004. New York: Routledge.

- Staging Consciousness: Theater and the Materialization of Mind 2002. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan P.

- Antonin Artaud 1976. New York: Penguin.

- The Return of the Visible in British Romanticism 1993. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins UP.

- Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became "Shakespeare" 2004. New York: W. W. Norton.

- The Challenge of Coleridge: Ethics and Interpretation in Romanticism and Modern Philosophy 2001. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State UP.

- Holy Theatre: Ritual and the Avant Garde 1981. New York: Routledge.

- Avant Garde Theatre 1892-1991 1992. New York: Routledge.

- Angels in America: Part One: Millennium Approaches 1992. New York: Theatre Communications Group.

- Consciousness, Literature, and Theatre 1997. New York and London: St. Martin’s.

- Theatre and Consciousness: Explanatory Scope and Future Potential 2005. Bristol, UK and Portland, OR: Intellect Books.

- “Coleridge and the 'modern Jacobinical Drama': Osorio, Remorse, and the Development of Coleridge’s Critique of the Stage, 1797-1816” Bulletin of Research in the Humanities Winter 1982. vol. 85 no. 4 pp. 443-464.

- “The Robbers and the Police: British Romantic Drama and the Gothic Treacheries of Coleridge's Remorse” European Gothic: A Spirited Exchange 1760–1960 Horner, Avril (ed.) 2002. Manchester and New York: Manchester UP. pp. 128–146.

- A Mental Theater: Poetic Drama and Consciousness in the Romantic Age 1988. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State UP.

- British Romanticism and the Science of the Mind 2005. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

- The Neural Sublime: Cognitive Theories and Romantic Texts 2010. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins UP.

- A Course of Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature Black, John (ed.) 1973. New York: AMS Press.

- Sam Shepard 1997. New York: Da Capo Press.

- Creating a Role Hapgood, Elizabeth Reynolds (ed.) 1961. New York: Theatre Arts Books.

- Open Letters to the Intimate Theater Johnson, and Intro. Walter (ed.) 1967. Seattle and London: U of Washington P.

- “The Ghost Sonata” Strindberg: Five Plays Carlson, Harry G. (ed.) 1983. Berkeley: U of California P.

- “Seeing Things ('As They Are'): Coleridge, Schiller, and the Play of Semblance” Studies in Romanticism2004. vol. 43 no. 4 pp. 537-55.

- Sacred Theatre 2008. Bristol, UK and Portland, OR: Intellect Books.