Background

During the spring 2006 semester, I taught a senior-level course in British Romantic Drama for English majors, a course that satisfied for them a genre upper-division requirement. My first-day assessments of my students revealed that several had taken an introductory course in drama, and some had taken a junior-level course in Shakespeare, but no one enrolled in the course had pursued a course in the Romantic period. This course was, therefore, the students’ only contact with the Romantic period as well as a course involving the reading, discussing, writing, and performing of drama from the 1780s to the 1830s.

During the spring 2005, when I was teaching the senior capstone course in English, I included Joanna Baillie’s 1798 Plays on the Passions (Count Basil, The Tryal, and De Monfort) in a culminating activity I termed “The Baillie Project,” and during the fall 2006 semester, I included Baillie’s Count Basil in a sequence of plays for an Honors College course entitled Introduction to Drama: Tragically Monstrous, a course that is offered as a First-Year Experience requirement for incoming Honors College students. The first-year students read Count Basil in tandem with Euripedes’ Medea and Shakespeare’s Othello. When I teach the junior-level course in the British Romantic period, I routinely include two or three dramas, including Count Basil and Thomas Bellamy’s 1789 The Benevolent Planters (both are anthologized in Mellor and Matlak’s British Literature 1780-1830). And when I teach the graduate-level course in British Romantic literature, I add P. B. Shelley’s 1819 The Cenci and Lord Byron’s 1822 Manfred to the two plays from the undergraduate course. My point is that while I had integrated Romantic drama into other courses I had taught, I had never taught an entire course devoted to Romantic drama until the spring of 2006. In spring, 2007, I taught the graduate version of the course as an Advanced Problems topic entitled British Romantic Drama. This course was actually a “piggy-back” course in that it was taught as a graduate seminar and an Honors College seminar for 4000-level credit for English majors and minors with the appropriate prerequisites.

Course Description

To help students identify what a course entitled Senior Seminar in Studies in Drama: British Romantic Drama was about, I supplied the following description, which provided them a sense of the cultural and political aspects of the course we would emphasize as well as strategies they could use for reading the plays:

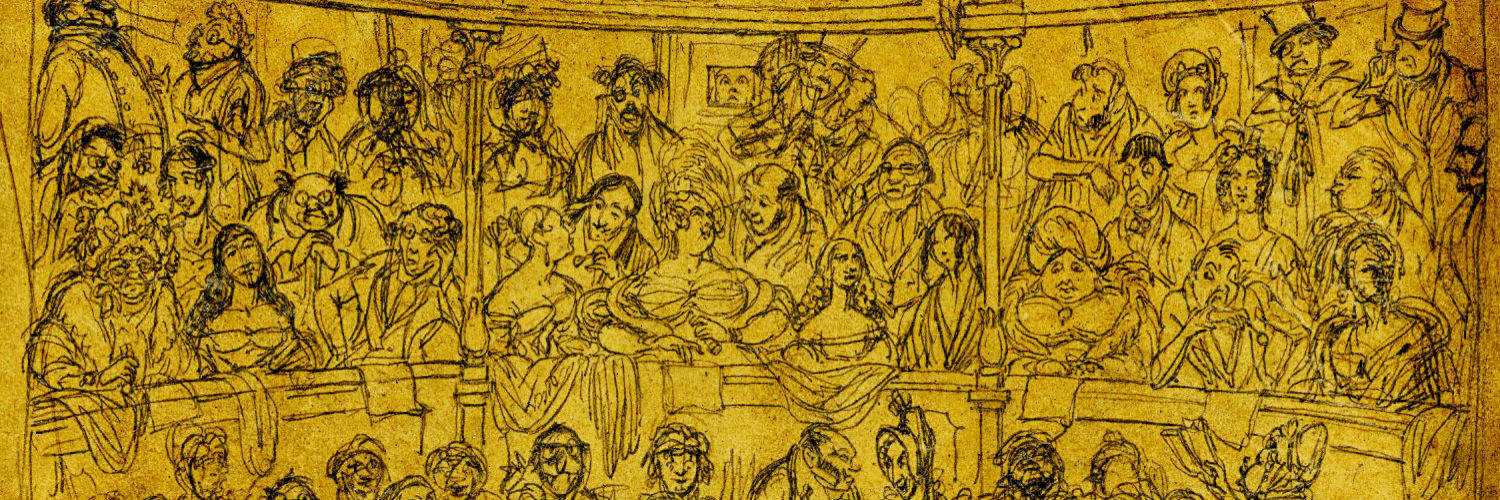

After more than a decade of recovering and recontextualizing Romantic drama in Great Britain, we have come to recognize the central role that drama played during the period. Romantic drama, staged and read, was its culture’s most popular medium, crossing class, national, and gender divisions, as well as a serious literary form written by the period’s major writers. Manifested in diverse ways (melodrama, gothic, verse drama, opera, pantomime, puppet shows, children’s drama, monodrama, tragedy, comedy, burlesque), Romantic drama performed, reflected, and influenced the political, social, and cultural issues of its day. The Licensing Act of 1737, granting patents to the Royal Theatres of Drury Lane, Covent Garden, and the Haymarket, and the Lord Chamberlain’s censorship (willingness to grant performance licenses) meant that playwrights had to be clever in their stagings of controversial and taboo subjects.

In this seminar, we will examine diverse plays from the period as negotiations of theatrical politics. We will look at the performative aspects of Romantic drama, including the role of the actor, the design of stages, non-dramatic performances (such as itinerant medical shows), and private theatricals. We will consider the thematic and dramaturgical handling of the revolutionary and changing Romantic culture from which its drama emanated. We will contextualize the ways in which Romantic drama engaged with the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries as British society became increasingly democratized, commercialized, and bourgeois. We will discover how the theatre was a site for performing gender and how playwriting was particularly problematic for women. We will situate Romantic drama in the history of theatre.

Textbooks

- Baillie, Joanna. Plays on the Passions. 1798. Ed. Peter Duthie. Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2001. ISBN: 1-55111-185-3

- Cox, Jeffrey N., and Michael Gamer, eds. The Broadview Anthology of Romantic Drama. Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2003. ISBN: 1-55111-298-1

Teaching Philosophy

I ask students to come to this seminar prepared to engage in interactive learning, to be willing to explore all dimensions of Romantic drama as reading and performance texts, as stage spectacles, as serious commentary on the period and its culture. I inform them during our first class meeting that because my pedagogy and scholarship are informed by feminism and feminist theory, they will encounter a learning environment of decentralized authority with an invitation to participate in their own learning/discovery process, their own knowledge- and meaning-making. I tell them that because Romantic drama is a genre that uses performance as well as the printed page, they should be prepared to engage in some reading and performance activities that will require them to learn affectively as well as intellectually. Students are given multiple opportunities to pursue their own interests and lines of inquiry involving the drama, and my writing and discussion prompts are directive but open-ended.

Learning Outcomes

If you successfully complete this course, you should be able

-

To interpret knowledge of the human condition, as reflected in British Romantic drama, in its diverse generic manifestations and from various theoretical perspectives;

-

To identify current and historical developments in studies of British Romantic drama;

-

To analyze theoretical and critical arguments about British Romantic drama and the Romantic theatre;

-

To integrate primary and secondary source evidence into analytical writing that presents close textual readings;

-

To assess the ways in which British Romantic drama and scholarship about it have contributed to our understanding of Romanticism.

Learning Outcomes Assessments

-

Writing response papers that require you to summarize, to explicate, and to judge the content of assigned Romantic dramas;

-

Contributing to seminar discussions with analyses, comparisons, contrasts of Romantic dramas as well as the scholarship on Romantic dramas;

-

Conducting a brief literature search of relevant secondary materials and assessing their importance to close readings of Romantic dramas;

-

Reading and responding to contemporary performance reviews of assigned Romantic dramas;

-

Writing a research-based project that requires you to weigh, select, and apply close textual readings and critical studies of Romantic drama.

Other Course Objectives

-

To consider the ways in which Romantic drama has affected the field of Romantic literary studies and our understandings of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century British culture;

-

To recognize and validate diverse perspectives and experiences that inform our readings of Romantic drama;

-

To work out the particular performance dimensions of Romantic drama that are important to our understandings and appreciations of it as a unique cultural expression;

-

To foster professional development;

-

To collaborate in the learning/discovery/sharing process;

-

To learn something about ourselves and our responses to literary expressions;

-

To enjoy reading Romantic drama and the discovery activities which enrich our understandings and appreciation of Romantic literature.

Course Policies

-

Come to class ready to share and to learn. Read assignments and bring texts of the plays with you to class;

-

Attendance is required for you to pass this course;

-

All assignments must be submitted for you to receive a passing grade;

-

All assignments must be prepared according to my instructions;

-

Maintain academic integrity. The deliberate use of someone else’s language, ideas, or original material without acknowledging its source constitutes plagiarism. Plagiarism is intellectual dishonesty and thievery. If you plagiarize, you will fail the course, and the incident will be reported to the university.

-

If because of a disabling condition, you require some special arrangements in order to meet course requirements, you should let me know. Please present appropriate verification from Student Disability Services, Access TECH.

-

If you are absent from class for the observation of a religious holy day, you shall be allowed to make up assignments scheduled for that day within a reasonable time after the absence if, no later than the fifteenth day after the first day of the semester, you have notified me of each scheduled class that you will miss for a religious holy day.

Learning Environment

-

This is a discussion/participation seminar. Everyone should feel free to contribute ideas, experiences, knowledge, reactions; therefore, we need to maintain an environment in which everyone’s opinions and perspectives are respected and valued. From our diversity, we can multiply what we share and learn. Help us to maintain an environment conducive to interactive learning by turning off cellular phones and beepers, by arriving on time, and by avoiding distracting behaviors.

-

In this seminar, your voice is valuable and valued. Be willing to assume an active role in your learning/discovery process.

-

Our reading, activities, and schedule will be fluid and flexible, and you are invited to help shape what we pursue and emphasize.

-

Because Romantic drama is a genre that uses performance as well as a kind of literary text, we will engage in some reading and performative activities that will require you to be willing to engage with our readings in more than intellectual ways. Be open to new ways of reading, learning, and responding.

-

Because some of the topics at the heart of Romantic drama involve gender, class, and race, you may discover materials in this course that present issues, language, and affective areas that are sensitive. It is important, therefore, for us to be sensitive to our colleagues’ needs, feelings, and responses to these matters.

-

Enjoy the community, personal growth, and professional development this seminar hopes to engender.

Course Requirements and Grade Determination

-

3 Response Papers (3-5 pages each) = 300 points (100 points each)

-

2 Discovery Activities = 300 points (150 points each)

-

Attendance/Participation/Performance = 100 points

-

Researched Critical Analysis = 300 points

-

Total Points = 1000 points

-

Grading Scale: 90% = A, 80% = B, 70% = C, 60% = D

Tentative Assignments Schedule

|

Response Paper #1 |

Thursday, January 31 |

|

Response Paper #2 |

Thursday, March 23 |

|

Response Paper #3 |

Tuesday, April 25 |

|

Discovery Activity #1 |

Thursday, March 2 |

|

Discovery Activity #2 |

Tuesday, April 11 |

|

Researched Critical Analysis Proposal |

Tuesday, February 14 |

|

Research Critical Analysis |

Thursday, May 4 |

Tentative Reading Schedule

|

Thursday, January 12 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. vii-xxxiv and 325-329 |

|

Tuesday, January 17 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. 311-317 |

|

Thursday, January 19 |

Every One Has His Faults (C&G 39-74) |

|

Tuesday, January 24 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. 318-325 |

|

Thursday, January 26 |

The Tryal (Duthie 217-298) |

|

Tuesday, January 31 |

Catch Up |

|

Thursday, February 1 |

De Monfort (Duthie 301-387) |

|

Tuesday, February 7 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. 380-383 |

|

Thursday, February 9 |

Duthie, pp. 424-458 |

|

Tuesday, February 14 |

Catch Up |

|

Thursday, February 16 |

Orra (C&G 133-64) |

|

Tuesday, February 21 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. 370-378 |

|

Thursday, February 23 |

Remorse (C&G 165-204) |

|

Tuesday, February 28 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. 389-392 |

|

Thursday, March 2 |

Catch Up |

|

Tuesday, March 7 |

Catch Up |

|

Thursday, March 9 |

The Cenci (C&G 221-259) |

|

Tuesday, March 14 |

Spring Break |

|

Thursday, March 16 |

Spring Break |

|

Tuesday, March 21 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. 393-398 |

|

Thursday, March 23 |

Catch Up |

|

Tuesday, March 28 |

Catch Up |

|

Thursday, March 30 |

Count Basil (Duthie 117-213) |

|

Tuesday, April 4 |

Catch Up |

|

Thursday, April 6 |

Catch Up |

|

Tuesday, April 11 |

Catch Up |

|

Thursday, April 13 |

Sardanapalus (C&G 261-309) |

|

Tuesday, April 18 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. 398-392 |

|

Thursday, April 20 |

Blue-Beard (C&G 75-96) and Timour the Tartar (C&G 97-116) |

|

Tuesday, April 25 |

Catch Up |

|

Thursday, April 27 |

Cox & Gamer, pp. 329-351 |

|

Tuesday, May 2 |

Last Day of Class |

Descriptions of Assignments

Discovery Activities

-

Write the working title and thesis of your Critical Analysis;

-

Outline your major points of development as you see them at this time;

-

Provide complete bibliographical entries for your secondary sources in MLA Style. If you need to review MLA Style specifications for your sources, use this website: www.lib.ttu.edu/reference/style/htm;

-

Indicate briefly how each source will be useful to your Critical Analysis, support or refute your thesis, demonstrate points of development, explain evidence, etc.

-

Romanticism on the Net: www.ron.umontreal.ca

-

Romantic Circles: www.rc.umd.edu

-

British Women Playwrights Around 1800: www.etang.umontreal.ca/bwp1800

-

Romantic Chronology: www.english.ucsb.591/rchrono

-

Studies in Romanticism

-

Nineteenth-Century Contexts

-

The Wordsworth Circle

-

Romanticism

-

Women’s Writing

-

The Keats-Shelley Journal

-

The Byron Journal

-

Studies in Nineteenth-Century Literature

-

European Romantic Review

-

Prism(s): Essays in Romanticism

-

The Keats-Shelley Review

-

Gothic Studies

-

What do we learn about scenery, costuming, actors, audience, critical opinions, and the entertainment value of the play?

-

What about the play was especially popular and/or controversial?

-

How do the reviews offer us insights about the play that we might not otherwise perceive from our reading of the text?

-

Who would be your primary audience? Why?

-

Would you stage or shoot the entire play, or would you make cuts? Where and why?

-

How might you make the play relevant to contemporary audiences, such as manipulating the special effects, casting star performers, creating fantastic scenery and music?

-

What do you learn about the play by imagining it from a director’s point of view or from the perspective of performance rather than from the position of literary student/scholar?

-

Working title and thesis (argument or position) of your project;

-

Play(s) that will be included as primary source material;

-

Working major points of development and critical approach (i.e., historical, feminist, Marxist, post-colonial);

-

Tell me what you hope to accomplish (beyond the grade) in this project. (Can it be useful for you beyond this course, for example?)

-

List the secondary sources you have investigated as relevant to your project and indicate how you plan to use these materials (rely on Discovery Activity #1 here);

-

List any difficulties or questions you perceive at this point in the planning and development of your Researched Critical Analysis.

-

Make your position (thesis) focused, directional, argumentative, and specific;

-

Discuss a limited number of supporting or major points of development;

-

Draft a 3-5-page position paper using your own knowledge (including all class-derived materials) and the play(s) you are analyzing or including in your project—exhaust what you know in this draft that involves a close reading of your text(s)—here’s where one or more of your Response Papers may be useful;

-

Begin each supporting point with a clear topic sentence, and practice good paragraph development;

-

Select evidence from the play(s) you are including in your analysis (primary-source evidence);

-

Analyze your audience carefully, for it is crucial to your argument. Select the best quotations and paraphrases from primary and secondary sources to support your major points of development and your argument (thesis);

-

Set up the context of evidence (primary and secondary) for your audience and make reasonable connections between evidence and your major points of development, and then between that supporting point and your thesis;

-

Contextualize adequately the evidence for your readers—help them to access it and then to see its importance to your argument;

-

Insert primary-source evidence correctly (use MLA Style for in-text citations) and explain it thoroughly;

-

Turn to your five secondary sources to supplement your discussion (at least one must be a journal article, and only two may be derived from online sites);

-

Follow MLA Style (in-text or endnotes) in citing secondary source materials (summaries, paraphrases, quotations);

-

Use secondary sources only to supplement your discussion, to demonstrate your knowledge of current scholarly discourse about British Romantic drama. Points of agreement or disagreement might be included in your discussion or packaged as endnotes. Remember that the analysis should reflect your thesis, arguments, developments, and discussion. Keep the number and length of all direct quotations to a minimum. You are the primary author of this researched critical analysis.

Attendance/Participation/Performance

Discussion of Course Sequence and Pedagogical Strategies

The selection and sequencing of the dramas for the course reflects quasi-chronological progression, quasi-generic groupings, and thematic clustering so that plays can be read dialogically.

One reason for my including so much drama by Joanna Baillie is that about one third of my students needed to satisfy a major requirement for a single author, and so they were able to do so by taking this course that highlighted Baillie as its major playwright. I tried to include representative plays by male and female playwrights, but we began with three late eighteenth-century comedies by women: Hannah Cowley’s A Bold Stroke for a Husband (1783), Elizabeth Inchbald’s Everyone Has His Fault (1793), and Joanna Baillie’s The Tryal (1798). These comedies opened onto discussions of Georgian courtship and marriage customs that cast men and women in stereotypical relationships that favored men. We discovered how Cowley displaces British manner and customs onto Madrid, and, like Baillie, relies on disguise and cross-dressing to suggest gender-bending in which women gain control over their lives. Inchbald’s comedy, we agreed, brings the legal issues of divorce, custody, adoption, bankruptcy, and robbery into the contexts of women’s rights and gender stereotypes. While A Bold Stroke for a Husband is also a play that stages ambivalent, gender-bending heroines, we looked at how gender was even more complicated in performances featuring Mary Robinson as Victoria. All three plays show the centrality of marriage for women of Georgian Britain. All three comedies also push generic bounds. Cowley deploys conventions of Spanish intrigue and recycles the motifs of the comedy of manners.

Inchbald’s play resonates with pathos of character and novel-like structure. Baillie’s comedy revolves around subplots of play-making; Marianne and Agnes are themselves playwrights in this metadramatic comedy. Because these comedies are critical of the culture’s dominant practices, the students find them fun, but they help to draw students into Romantic period culture as well as into the playwrights’ resistance to its dominant ideologies.

We next turned to tragedies, beginning the next cluster of plays with Baillie’s De Monfort (1798), Orra (1812), and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Remorse (1813)—three plays that address sensibilities of the early nineteenth-century, including the Gothic. In De Monfort, we continued our exploration of gender-bending strategies, but here in tragic forms, and we considered whether or not the play holds up a tragic hero for emulation or admiration, whether it hints at homoerotic or incestuous relationships, and whether it presents the tragic consequences of immoderate passions, especially hatred.

We learned how Baillie stages the Gothic, more fully developed, in the kidnapping and brainwashing of the tragic heroine in Orra. Like the other plays we had read, Orra puts marriage center stage, as well as the heroine’s resistance to patriarchal control. We found that Orra also demonstrates the power of storytelling and the consequences to those whose naïve understandings of the world give them limited critical ability to discern reality from fiction. Similarly, Remorse, we agreed, explores gender-bending and mistaken identities so as to expose the fallacies and inconsistencies in social orders that are shaped by misogyny. While Baillie’s tragedies explore the crises for female identity and expose the subjection of femininity within patriarchal structures, Coleridge’s tragedy brings early nineteenth-century constructions of masculinity under scrutiny. All three plays can be read through postmodern lenses as historically specific—both in terms of their medieval settings and their Romantic-era contexts of composition—enactments of gender; the tragedies’ theatricality and performance, furthermore, expose the artificiality and even the fluidity of gender roles and gendered behaviors at the very time when codifications of those roles were being scripted off-stage as well as on-stage.

The next grouping of tragedies—P. B. Shelley’s The Cenci (1816), Baillie’s Count Basil (1798), and Lord Byron’s Sardanapalus (1821)—took us into deeper and darker spaces of Romantic thought by way of historically based incidents and characters. All three of these plays involve despotic rulers of corrupt governments, but they similarly feature stories of dysfunctional families, thus bringing the crises of public and private spaces together in shared space on the stage. The Cenci, like De Monfort from the previous cluster, is a play that opens onto discussions of censorship and licensing of plays in the Romantic period. The settings of Italy for Cenci and Basil, and Assyria for Sardanapalus offer spaces where taboo and disturbing issues affecting early nineteenth-century British culture could be displaced and displayed. These three tragedies open onto explorations of criminal behavior and punishment, the efficacy of language, the function of the public body, and the pathology of madness. Count Basil exposes the folly of excessive passions, coded masculine or feminine, and the segregated and gendered spaces that impede an individual’s healthy participation in the public sphere. P. B. Shelley’s tragedy presents us also with the problem of morality sanctioned by state and religion. Sardanapalus adds layers of colonialism and orientalism to its questioning of gendered agency and effective leadership. All three tragedies hint at Romantic preoccupations with transgressive public figures under surveillance and then put on trial for their moral and legal infractions.

As afterpieces to the course, we read George Colman the Younger’s Blue-Beard; or Female Curiosity! (1798), and Matthew Lewis’s Timour the Tartar; A Grand Romantic Melo-drama in Two Acts (1811), two plays that demonstrate to students the kind of experimentation that was occurring with drama, particularly staged drama, during the Romantic period. These two fantasies are fanciful but disturbing in their staging of the abuses of misogyny and of orientalism (both set in the Near East) under the guise of children’s theatre, harlequinade, pantomime, and spectacle. Both Bluebeard and Timour are representations of actual figures whose stories become thoroughly mythologized and fantasized. Their stories and depictions, like that of Beatrice Cenci, have been replayed in multiple forms—theatre, novels, visual arts, opera, and film—and we talked about why Romantic theatergoers would find these characters so interesting and engaging.

To supplement each clustering of dramas, we read, as the schedule above indicates, the performance reviews that Cox and Gamer have included in the Broadview anthology and that Duthie has included in his edition of Plays on the Passions and that are relevant to the play we are discussing. The creative discovery activity enables students to work closely with these reviews and to think critically about performance aspects of the plays. Graduate students work beyond the reviews of the anthology, seeking additional performance information and reviews from online and traditional scholarly sources in the preparation of their assignment. They may also look at reviews of contemporary stagings of Romantic plays.

Pedagogical Strategies

As the syllabus indicates, our class frequently read parts aloud (often in character) to get a feel for the language and the performance aspects of the play. For example,

-

From A Bold Stroke for a Husband, we read aloud act 2, scene 2 (pp. 12-15 from the Cox and Gamer edition) and act 4, scene 1 (pp. 25-27)

-

From Everyone Has His Fault, we read aloud act 2, scene 1 (pp. 46-54) and act 3, scene 1 (pp. 55-57)

-

From The Cenci, we read aloud act 5, scene 4 (pp. 253-55) and act 5, scene 4 (pp. 257-59)

-

From The Tryal, we read aloud act 1, scene 1 (pp.219-228 of the Duthie edition)

-

From De Monfort, we read aloud act 2, scene 1 (pp. 320-28) and act 5, scene 2 (pp. 373-79)

Sometimes for these oral readings, we wear masks. I have a collection of paper cardboard masks that can be easily distributed and worn from such sources as Madame Tussaud’s Book of Victorian Masks, Venetian Masks, and Famous Figures Historical Masks.

Occasionally, students make their own masks for the parts they are reading.

Additionally, I rely on a select but valuable collection of AV materials to supplement our readings and discussions of these plays. When students entered the classroom on the first day of class, they were greeted by the sounds of the CD Playhouse Aires: 18th-Century English Theatre Music, performed by The London Oboe Band to set the stage for the Introductory reading in the Cox and Gamer Broadview anthology.

With A Bold Stroke for a Husband, I played excerpts from the CD A Bold Stroke for a Husband, from the production directed by Frederick Burwick, original music composed by Brian Holmes. Burwick and Paul Douglass have created an invaluable resource, a website entitled “Theatre and Popular Songs, Catches, Airs, and Art Songs of the Romantic Period,” which features CD recordings at nominal cost, thereby making them accessible for pedagogical use.

Two other recordings Burwick and Douglass have made and that are useful for the teaching of British Romantic drama are the recording of a live performance of Thomas Lovell Beddoes’s Death’s Jest-Book: A Grotesque Musical Comedy and Inchbald’s Animal Magnetism.

As we moved to the cluster of tragic plays with gothic overtones, I introduced the cluster with a small segment of the video of the Readers’ Theatre production of A Tale of Mystery (1806) that was performed and video-taped at the 2003 meeting of the International Conference on Romanticism at Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The setting of the reading in the St. Joan of Arc Chapel on the Marquette University campus was a spectacular way for students to get a visual clue about how to read settings in De Monfort, Orra, and Remorse. The live accompaniment of the reading gave students a sense of how music was, in fact, a vital component to the play—something I asked them to pay close attention to in their readings of the plays’ stage directions. Likewise, our reading and discussion of Count Basil was enriched by two video supplements. In March of 2002, in celebration of Women’s History Month, the Women’s Studies Program and the Theatre Department at Texas Tech University worked together to present a parlour reading of Romantic period dramas by Felicia Hemans, Elizabeth Inchbald, and Joanna Baillie. We held the reading in the parlor of a local, private home, and relied on student and faculty volunteer performers, and I served as dramaturg for the production. We videotaped the performance, and thus, I have a segment of Count Basil as amateur readers’ theatre that I can show the students. In August of 2003, the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism brought a Horizons Theatre production of Count Basil to Fordham University, Lincoln Center Campus for the association’s annual meeting. Having procured a DVD recording of that professional production, I can show my students parts of the play or the entire performance of Count Basil. I can also refer students to reviews of that production that were published in European Romantic Review.

To enrich our readings of The Cenci, Sardanapalus, Blue-Beard, and Timour the Tartar, I relied on reproductions of artwork, all of which are easily available online for showing in class or for reproducing as handouts. In particular, we looked at the “Sirani Elisabetta Portrait of Beatrice Cenci” attributed to Guido Reni that P. B. Shelley saw in Palazzo Colonna in 1818. This visual served as a starting point for our discussion of the enduring interest in Beatrice Cenci, as demonstrated by the many revisions of her life story in plays, operas, novel, and film. For Sardanapalus, we looked at Eugène Delacroix’s painting The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827-1828 which is on display at the Louvre. For Colman the Younger’s play, we viewed Gustav Doré’s nineteenth-century illustrations of Bluebeard. Timour the Tartar became more accessible for the students with the visual enrichment of Skelt’s Scenes from the novel version of Timour’s story, J.K. Green’s illustrations of the characters and scenes of the play, and the playbill of Mrs. H. Johnston in the melodrama of Timour the Tartar. We also looked at a picture of the statue of Timur in Shahrisabz, Uzbekistan.

We rely on the online sites Romantic Circles, Romanticism on the Net, British Women Playwights around 1800, and Romantic Chronology for the enriching materials, scholarship, and visuals that these sites bring to students. For my graduate seminar, students work with at least one hypertext found on British Women Playwrights around 1800, or they work with a novel and its dramatic adaptation.

Sample Student Responses

In the creative discovery activity #2, one student took the reviewers of Joanna Baillie’s Plays on the Passions, in particular of an 1804 staging of Count Basil, to task. She writes: “…I find Baillie’s endeavors to capture the state of one passion incredibly impressive and thought provoking. The reviewers seemed to have missed some of the points of Baillie’s unchecked and exaggerated passions.” A researched critical analysis of Baillie’s Orra explores the “patriarchal-taught self-fear” that Orra experiences and its contribution to her madness. The student writes: “This self fear is beneficial to the patriarchal, hierarchal society because it keeps women in their ‘place’ by making them emotionally weak and easily scared. They either run to men for help and/or readily submit to men without question.” Another student astutely observes gender dichotomies: “[v]iolence directed at women in Romantic drama serves the masculine standard by placing the dramatic burden firmly on the shoulders of the female characters—both as actor and acted upon.… Clearly, Baillie is interested in how her contemporaries utilized violence and gender both to control action on stage and, in many ways, to control the making of this action.”

For the re-staging of The Cenci, one student elaborates on the scenery and costuming: “Lighting would be very warm, reds, oranges, and yellows…Once Count Cenci reveals the demise of his sons and openly celebrates their death, the brightness of the stage will begin to diminish and the darkness of the Palace will take over, like a foreboding shadow. Beatrice would, like the other characters, begin the play, except for Cenci, in drab and colorless apparel, but when she starts to plan her father’s murder, she changes to richly colored costumes so that by the height of her madness, she would be donning apparel almost equal to the richness and color of the costuming worn by Cenci.” Another student proposes a contemporary cast for a new film version of P. B. Shelley’s tragedy: Scarlet Johansen as Beatrice, Michael Douglas as Count Cenci, Jessica Lange as Lucretia, and Anthony Hopkins as Cardinal Camillo. As for an interesting stage effect at the end of the play, another student writes: “The Hall of Justice would be a long hallway, with the prisoners positioned at one end, each seated in a rolling office chair, and Camillo and the judges at the other. As characters are given their turns to speak, their chairs roll forward toward the judges, and as they are dismissed, their chairs will roll into a doorway off to the side of the hall.”

A response to 1813 reviews of Coleridge’s tragedy Remorse indicates how the student better appreciates the importance of the play’s scenery for spectators. He writes: “With these reviews, it was somewhat easier to imagine what key scenes would have looked like, the sorcery scene specifically. They also gave me a sense of what early nineteenth-century audience thought of acting capabilities. By giving our imagination a direction, the reviews let me see different perspectives, things I can’t see from merely reading the play.” Another student recommends Remorse for a made-for-TV movie, recast as a story about high-school kids and cliques. The outsider Alvar would be chunky and nerdy, and Ordonio would be thin and popular. Ordonio teases Alvar and spreads malicious rumors about his brother, eventually causing Alvar to transfer schools, despite the fact that Teresa finds him attractive. When Alvar returns to the school months later, he has lost weight, wears contacts, and is immediately a hit with the popular crowd.” Another student recommends filming Byron’s Sardanapalus for the big screen, with a setting in the 1940s in Washington, D.C. and involving a congressional scandal with a closeted effeminate male and a press leak, so that the story would be about the fall of democratic leadership rather than the fall of the Assyrian empire. Another student, however, sees contemporary appeal for a movie that retains Byron’s Near East setting, particularly given our political interests in the very region that was seen as vital to the emerging commercial economy of early nineteenth-century Britain. A passage from a researched critical analysis of Sardanapalus reveals how clothing becomes code for sexuality for this reader: “Clothing is used in this play to reveal Sardanapalus’ femininity, and Sardanapalus’s preoccupation with battle clothing makes him seem less of a man. When Sardanapalus orders his servant to bring him a mirror, we see his narcissism, his feminine concern with appearances rather than the impending battle for control of Nineveh.”

In general, the course evaluations for British Romantic Drama were similar to what I receive from other courses I teach, but here are some comments that are particularly relevant to the content and delivery of the seminar and that indicate how students were able to integrate the learning experiences. One student writes: “This class taught me something very different; reading drama can be just as fulfilling or more fulfilling than actually seeing a play read.” Another student points to the ways in which the drama contributed to his self-awareness: “I learned a lot about myself over the course of this semester in class. It took me a while to learn how to read the plays, but once I learned what worked, I fell in love with some of the plays we read. I wish I had taken a course in Romanticism before my senior year.” Another student emphasizes connections between self-actualization and the drama we read: “Through this class, I have been exposed to literature and drama that, up until this point, I had not heard of and I was able to learn. I think that the most important thing that I have learned about myself this semester is that I really enjoy reading drama and that I am drawn to these plays because of their interesting content. I think that groupings of the plays are helpful since it allows for progression through the semester with smooth transition between plays.” And finally, a student admits ending up in this course quite by happenstance, but finds it a surprisingly pleasant and instructional experience: “This class has been an invaluable learning experience for me. I thoroughly enjoyed the curriculum and loved learning about, for me, a new kind of drama. Joanna Baillie was my favorite dramatist, and I must confess that I took this course because the Shakespeare class was full, but I am very glad that I had this opportunity.”

Expected Outcomes

At the end of the semester, I was able to report to my department chair that students who successfully completed English 4312: Studies in Drama: British Romantic Drama during the spring 2006 were able to write analytical essays that summarized, explicated, and judged diverse cultural expressions in the plays we read. The students contributed to class discussions with analyses, comparisons, contrasts, and presentations of experiential knowledge informed by close textual readings of Romantic drama and reviews. The students demonstrated generic and periodic understandings of how literary and language studies function through their response papers and the researched critical analysis. The students integrated understandings and applications of skills acquired through the study of literature and language as part of their last response paper (see Appendix), which required them to perform a self-assessment and to discuss the ways in which the skills and strategies they had acquired in this course would be helpful to them in the future. Finally, the students composed a research essay in which secondary materials supplement and support close readings of the drama, an essay that was built, in part, by the cumulative assignments of the secondary source discovery activity, the response papers, the critical analysis proposal, and class discussions. By the end of the course, most students were able to identify historical and current developments in the study of British Romantic drama and were cognizant of the ways in which British Romantic drama reflected the cultural and historical issues of the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries.