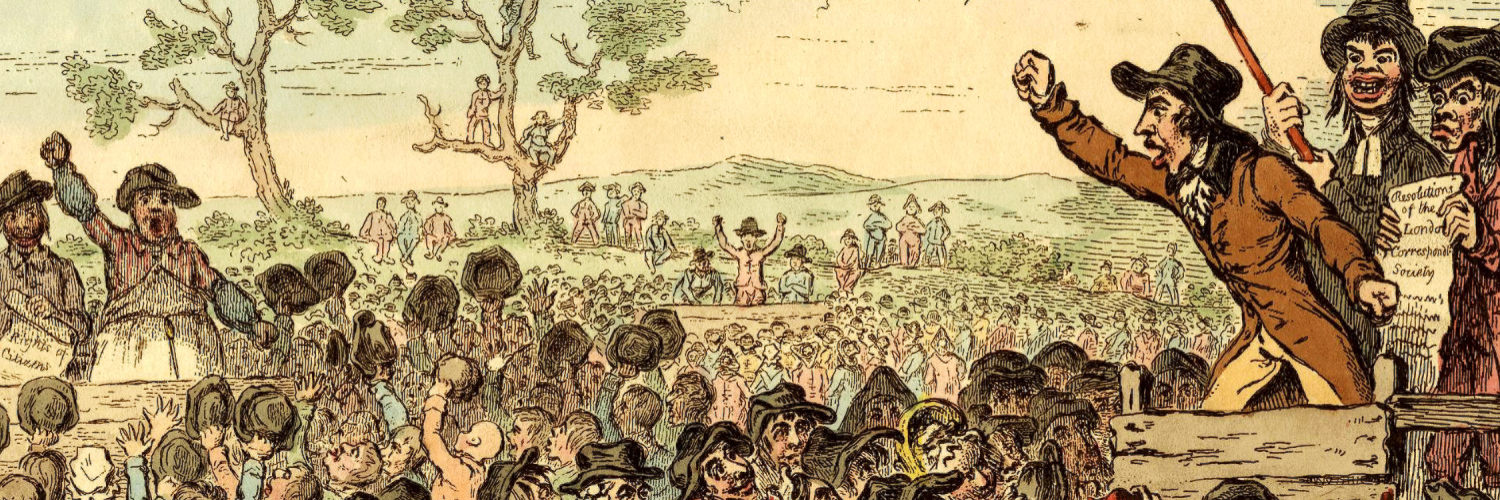

In the early Romantic period, John Thelwall was infamous for both his defiant volubility and subsequent silencing. According to E. P. Thompson, “the story of the silencing of Thelwall” (95) begins in 1795 with the passage of the Treasonable Practices Act and the Seditious Meetings Act and culminates with Thelwall’s decision to become a teacher of elocution—a decision signaling that “nothing survived of the Patriot except his fading notoriety” (123). Perhaps no portrait better captures the drastic turn in Thelwall’s career than George Crabbe’s caricature of Thelwall as the radical lecturer Hammond in the verse tale The Dumb Orators; or, the Benefit of Society (1812).

In The Dumb Orators, Hammond first stupefies a Church-and-State orator using “Deist’s scorn” and “rebel’s wit,” but later gets his just deserts when the political tide turns (192). Hammond, who ironically earlier used “licentious words” to prove “that liberty of speech was gone,” ultimately devolves into a stuttering isolate (223-24). Under the critical eyes of loyalists, Hammond loses the liberty of speech that he prematurely lamented:

I seek no favour—I—the Rights of Man!Claim; and I—nay!—but give me leave—and IInsist—a man—that is—and in reply,I speak. (455-58)

Though a smug parable, Crabbe’s tale had its basis in reality. Thelwall, who had overcome a speech impediment of his own, lectured to thousands in the early 1790s, but by the end of the decade he had been made, effectively, dumb: first by the “Gagging Acts” of 1795 and then by “dwindling interest” in his public lectures (Claeys xxvii).

Forcibly deprived of the freedom to express his political views, Thelwall changed careers to become an elocutionist who sought to cure speech impediments, mutism, and “moral idiocy”—conditions that had formerly been the province of “deaf and dumb” schools (Henry Cline 124, 84).

As Thompson’s account suggests, Thelwall’s elocutionary career has frequently been understood as a renunciation of his revolutionary politics. Thelwall himself encouraged this view, claiming that his “New Profession” returned him to the “calmness of physiological disquisition” he had experienced as an auditor of medical lectures at Guy’s Hospital before he was “hurried . . . away” by the “excentric fire of youth” into politics (Henry Cline 2). Thelwall scholars such as Judith Thompson, however, have questioned this account and argued that Thelwall’s “speech theory emerges as part of a total system to reform the body politic” (“Re-sounding Romanticism” 24). Though a number of scholars have drawn connections between the scientific materialism that informs Thelwall’s speech theory and the political materialism that informs his revolutionary opinions, there has not yet been a thorough explanation of how Thelwall thought an “enfranchisement of fettered organs” would manifestly contribute to an expansion of the franchise (Henry Cline 9). In other words, how did Thelwall see his work as an elocutionist as a continuation of his work as a political activist? In this essay I begin to answer this question by uncovering the model of mind that guides both Thelwall’s elocutionary work and his political philosophy. First, I establish the model of the mind Thelwall develops in elocutionary texts such as A Letter to Henry Cline (1810). Then, I turn to Thelwall’s An Essay Towards a Definition of Animal Vitality (1793), an early “physiological disquisition” that provides the scientific basis for his model of mind and speech theory. Finally, I look at the rhetoric of Thelwall’s arguments in support of free association to show that Thelwall’s scientific interests inform both his political philosophy and his elocutionary theory.

1.

In a recent article, Judith Thompson compares Coleridge’s conversation poems to Thelwall’s and concludes that Thelwall is “more concerned with modulations of voice than associations of the mind, and with building a co-responding society than with correspondent breezes” (“Why Kendal?” 18).

I agree with Thompson’s assessment that Thelwall, unlike Coleridge, maintained his political ideals even in retirement. However, as I will show, Thelwall also maintained a commitment to associationist psychology. In fact, I argue that it is precisely because of his continued commitment to associationism that Thelwall was able to continue his reformist agenda after he became an elocutionist. As we will see, for Thelwall modulations of voice are not opposed to associations of the mind but rather depend on them. Likewise, strong corresponding societies depend on strong correspondences in the brain.

Thelwall explicitly attests to the power of mental associations in “On the Influence of the Scenery of Nature on the Intellectual and Moral Character, as well as the Taste and Imagination” (1820), an essay first published in his newspaper The Champion. Here, many years after Coleridge rejected Hartleian thought, Thelwall continues to appeal to associationist theory.

In his essay, Thelwall refutes two anonymous writers who deny that our natural environment has any influence on our intellectual or emotional identity. Thelwall rejects their claims, saying that if we did not immediately see their denials as “Affectation” we would pronounce them to be “the verbiage of idiotism” (74). Neglecting the importance of scenery to our internal state is “idiotism” according to Thelwall because it denies “the whole doctrine of associations” and turns a human being into ‘a sort of abstract entity whose ideas are all innate and independent of perception; and whose senses are mere superfluous appendages, not ministers to his intellectual perfectibility: a sort of filigree on the outside of a tea caddee, that neither contributes to the flavour nor the preservation of the aromatic luxury within. (74) ’ Unlike the filigree, or decorative work, on the outside of a tea caddy, which plays no part in keeping tea fresh, the senses are instead like the material of the caddy itself, which contributes to the flavor of the tea. The metaphor is not perfect: whereas the caddy isolates the tea from external influence, the senses do the exact opposite, allowing exterior images and scenes to enter into, impress, and change the mind. Yet, despite the imperfection of the metaphor, it nonetheless sheds light on Thelwall’s model of mind and its connection to his political theory. In Thelwall’s image of the mind-as-tea-caddy, perceptions associate thoughts and, through progressive influence, lead a person toward (or away from) what he calls “intellectual perfectibility” (“On the Influence” 74). Whereas Wordsworth famously illustrated the integration of mind and nature by tracing “the manner in which we associate ideas in a state of excitement” (597), Thelwall used associationism to provide philosophical evidence that lived conditions and intercourse with others influenced how citizens experienced their world and, in turn, influenced their ability to contribute to that world.

It is fitting that Thelwall, who sought to explain vitality itself according to “the simple principle of materialism,” would imagine the mind as a tangible object and, moreover, as an object of commerce (Animal Vitality 13). By taking the “necessary luxury” of tea as his image, Thelwall universalizes what would normally be a private possession.

Thelwall suggests that though the mind, like tea, is a material object, it is not a commodity and does not gain value when locked against external influence.

On the contrary, he suggests that intellectual perfectibility is only possible when there is associative communication between the permeable borders of mind and world.

In his elocutionary treatises, Thelwall similarly represents the minds of those with speech defects as imperfect because of their impermeability. In both cases, mental associations are “ministers to . . . intellectual perfectibility” and, as such, can either create or inhibit a relationship between the body of the individual and the body politic (“On the Influence” 74). A speech defect occurs, Thelwall posits, when the mind cannot associate the intention to speak with the physical organs that produce speech. Those who want to talk simply cannot. Unlike many physicians of the time, Thelwall vehemently denies that “defects of organization have any thing to do with any of the various descriptions of Impediment” in speech (Henry Cline 54). Rather, Thelwall blames speech impediments on a “diseased association” of ideas brought on by miseducation or emotional trauma (Henry Cline 59). By proposing that speech pathology originates in the space between ideas, or in the mental action connecting ideas, Thelwall can also propose that such pathology requires educational, rather than medical, intervention. While this theory helped Thelwall market his services as a teacher of elocution, it also helped him to suggest that impediments to speech were also impediments to sociability, and ultimately, to participation in the public sphere.

The gravest consequence of speech impediments, for Thelwall, was the enforced antisociality that they caused. In his case study of a young woman with a severe speech defect, Thelwall’s goal was not to teach her to speak properly but to “rescue her from the misery of being in eternal solitude, even in the midst of society” (64). According to Thelwall, speech impediments were necessarily restrictive to sociality for two reasons. Not only did they keep a person from being able to speak, but they also impaired a person’s willingness to speak.

Both prevented individuals from developing bonds with society. Thelwall went so far as to call speech impediment a kind of idiocy, a term used in the period for a variety of mental disorders that interfered with sociality. In his letter to Cline, Thelwall exclaimed: “What, but a species of idiotcy [sic], is it, to be ignorant of the means by which the will is to influence the simplest organs of volition, and (without excuse of palsy, stricture, or organic privation) to be unable to move a lip, a tongue, or a jaw?” (68). It is telling that Thelwall chose to call all individuals with speech defects “idiots” (Gk. “private person”), as the private, or isolated, “idiot” was necessarily excluded from the public sphere. As Avital Ronell explains, from Plutarch through the nineteenth century, “the term ‘idiot’ expresses social and political inferiority; it is not a certificate of citizenship—the idiot is the one who is not a citizen (politēs)” (41). Without the ability to associate the will to speak with the organs of speech, individuals with speech defects could not exercise their natural right of participatory citizenship. This right, Thelwall declared, “constitutes the essential attribute of our species” (Henry Cline 17). One of the major tenets of Thelwall’s political philosophy was that “man is, by his very nature, social and communicative” and “whatever presses men together . . . is favorable to the diffusion of knowledge and ultimately promotive of human liberty” (Rights of Nature 400). For Thelwall, individuals who could not communicate with others were unnaturally denied social freedom. To put it simply, impediments to speech were also impediments to liberty.

Thelwall described the process by which the teacher of elocution could cure the antisociality of his pupils and encourage them to rejoin society as follows: ‘restore, or produce those essential links of association, between the physical perception and the mental volition, and between the mental volition and the organic action, which either have some how been broken, or have never properly been formed—and the stammerer, the stutterer, the throttler, the endless reiterator, and almost the whole order of unfortunate persons, whose impediments consist in obstructed utterance, are relieved from their affliction: no matter what were the original circumstances that broke, or interrupted those associations . . . . (Henry Cline 58)’ However, Thelwall advised that in order to repair a pupil’s associative capacity, the teacher first had to “impress the [pupil’s] perceptive faculty” by appealing to her “imagination” (Henry Cline 58-59). In his case studies, Thelwall accomplished this by making his pupils verbally request the things they desired. Too often, Thelwall explained, a child with a speech defect would have her needs predicted and met without having to open her mouth. The harmful consequence of this was that she never learned to regard intelligible speech as a useful means of satisfying her desires, and as a result, often avoided speaking at all. The teacher’s first task, then, was to compel the pupil to communicate. To do so, Thelwall used “attractive object[s]” to awaken the pupil’s imagination and “impress” her perception by forcefully directing her attention to objects in the world (115). For example, if a pupil liked to gather honey, Thelwall required her to make her goal known to others before she would be allowed to travel to the beehive. She had to be prevented from using “the mute effort of solitary ingenuity” to meet her goal (124). Rather, her goal had to be “socially presented, as a motive for some proper species of exertion” (124). Thelwall believed that by exerting themselves in social interaction, pupils would be forced to unite objects of perception (such as honeycombs) with ideas of those objects and, eventually, with intelligible signifiers for those ideas. Thelwall maintained that if a pupil could consciously make links between perception and will through speech (however imperfect) she would also unconsciously create or repair associations in the brain. With re-formed associations, the pupil would then be able to associate the will and the body. She would be able to connect her desire to move her jaw with the muscles that moved her jaw and, thus, produce more perfect speech. Here, as in the example of the tea caddy, Thelwall used associationism to explain how perception of the external world influenced the will, which, in turn, bound the individual to the world.

2.

In attempting to strengthen the power of mental associations in his pupils, Thelwall was in a sense continuing his earlier efforts to strengthen the power of reformist associations. In Animal Vitality, Thelwall revealed the physiological basis of his associationist philosophy. Most notably, he established a materialist model of the mind that made it synonymous with the brain. As Alan Richardson has shown, the 1790s, like the 1990s, were “a decade of the brain,” in which models of the mind were revised in response to materialist advances in medicine and philosophy (2). The 1790s saw Joseph Priestley popularize David Hartley’s physiological associationism (1790), Erasmus Darwin theorize the embodied mind in Zoonomia (1794‑96), and Luigi Galvani publish his initial theory of animal electricity (1791). Thelwall was well aware of these major developments in brain‑mind science and evidenced this awareness in his writings.

One of Thelwall’s central goals in Animal Vitality was to disprove John Hunter’s theory that blood is the source of life. Instead, Thelwall asked his colleagues to consider that the “life of the animal is in the brain, rather than in the blood” (15). Although Thelwall indicated the primacy of the brain as an organ that registered vitality, he made it clear he did not want to “rob the blood of its vital honours, to bestow them on the Brain and Nerves” (29). Rather, Thelwall contended, vitality issued from integrated bodily organization motivated by a stimulus and identified the stimulus as the “electric fluid” (41). In suggesting that the electric fluid stimulated life, but was not itself living, Thelwall likely followed Erasmus Darwin, of whose work he was clearly aware.

In his medical treatise Zoonomia, Darwin claimed that “the electric fluid may act only as a more potent stimulus exciting the muscular fibres into action, and not supplying them with a new quantity of the spirit of life” (1.12.83). For Darwin, the word “stimulus” referred not only to the “application of external bodies to our organs of sense and muscular fibres . . . [but also to] desire or aversion when they excite into action the power of volition; and lastly, the fibrous contractions which precede association” (1.2.13). The electric fluid induced both muscular contraction and mental association. As Darwin put it, just as successive muscular contractions are associated with one another, ideas “are associated with many other trains and tribes of ideas” through excitation of the fibrous tissue in the body induced by the electric fluid (1.9.60). Thelwall seems to have agreed that the electric fluid was responsible for super-inducing absent associations or repairing broken ones. In his elocutionary texts, he stressed “the phenomena of the action and re‑action of the physical and mental causes—and the operation, in particular, of mental, moral, and educational stimuli upon the frame and fibre—the senses and the organic function” (Results of Experience 172). For the most part, the educational stimuli chosen by Thelwall was his own speech. Like the electric fluid, his speech was meant to excite the body of his listener into creating new associations. Because Thelwall claimed that “the individual body and the social body do exactly agree,” it is reasonable to conclude that he understood the speech of the political activist, like the speech of the elocutionary master, as a vital stimulus (Tribune 114).

Indeed, much the same model of mind surfaces in Thelwall’s political rhetoric. Just as the voice of the teacher of elocution re-formed associations in the minds of his listeners, the voice of the political orator reformed how his listeners associated with one another. As Nicholas Roe, Michael Scrivener, and others have noted, Thelwall used his medical knowledge to create particularly effective Jacobin analogies between a vital, organized human body and a vital, organized body politic.

To this I would add that it is the logic of associationist psychology that informs these analogies and makes them viable. In The Natural and Constitutional Right of Britons to Annual Parliaments, Universal Suffrage, and Freedom of Association (1795) Thelwall takes up the question of social association itself. Here, Thelwall argues for free association between citizens as the only means by which the power of the body politic can fairly counter the power of the king. Thelwall explains: ‘For as the Royal Power is concentrated in a single person, girt and surrounded by Ministers of his own appointment; and as the aristocratic body is also intimately encorporated, if the people are not permitted to associate and knit themselves together for the vindication of their rights, how shall they frustrate attempts which will inevitably be made against their liberties? The scattered million, however unanimous in feeling, is but chaff in the whirlwind. It must be pressed together to have any weight. Deny them the right of association, and a handful of powerful individuals, united by the common ties of interest, and grasping the wealth of the Nation, may easily persevere in projects hostile to the wishes, and ruinous to the interests of mankind . . . . (46, emphasis added)’ In this passage, Thelwall opposes the body of the King to the body of the people; the King’s power is consolidated in one physical body, and the power of the aristocracy is similarly “encorporated.” The people, however, lack such incorporation. As a consequence, Thelwall maintains, they must be given the freedom to associate in order to have the weight of a healthy body that can confront the power of the king man to man, as it were. James Robert Allard connects this passage to a similar passage in Rights of Nature to suggest that, “Thelwall again implies that organization, ‘press[ing] men together’ is necessary for reform” (72, emphasis added), However, it is clear here that what presses men together is association rather than organization. Though “organization” and “association” can be used interchangeably as nouns to mean “a body of people with a particular purpose” (“Organization,” def. 4a), as we saw in Animal Vitality, “organization” for Thelwall means the arrangement of elements within a larger system, such as organs in the body. But by “association,” as it is developed here and in the elocutionary texts, Thelwall likely means the act of people coming together to form a group with a common purpose. That is, only when citizens are allowed to gather together in the same space can they achieve what Georgina Green calls “embodied communication” (80). Although distinguishing between arrangement and act may seem like a minor point, it allows us to differentiate between the material structure of a system and the stimulus that joins together the elements of that system, allows communication between them, and thus vitalizes the whole. For Thelwall, it is not so much the structure that vitalizes the state, but the dynamic connections between people within that structure. As in the body, these dynamic connections are figured as material associations and, as we will see, the stimulus is figured as electricity. With the passage of the Seditious Meetings Act (which prohibited public meetings of over 50 people), associations became “diseased” and the speech of the citizens as “one heart, one voice, one sentiment” became as defective and antisocial as that of the individuals Thelwall would later treat (“Peaceful Discussion” 226).

The cure for the diseased associations of society, as for the diseased associations of the individual, was the intervention of a political teacher who could communicate the electric stimulus to his listeners. Noel Jackson persuasively suggests that, for Thelwall, the stimulus or electric spark that animates the state and keeps it vital is the printed press. As evidence, Jackson cites Thelwall’s development of Burke’s metaphor of the press as an electrical conductor. Burke regretted that the press encouraged middle-class ambition by carrying “electrick communication” throughout pre-revolutionary France (186). But Thelwall esteemed “that prompt conductor and disseminator of intellect, the press,” for the same reason (Rights of Nature 426). Moreover, Thelwall represented himself, and the press, as the instruments through which “electrick communication” traveled. Although Thelwall thought the printed word was important for associating people, he also made it clear that the press had limited efficacy when people were “scattered” throughout Britain and not allowed to gather in the same space (Natural Right 46). Thelwall cautioned that without the ability to publicly associate and, as a group, determine a course of action, people would be driven to form factions and exchange violent crime for peaceful protest. Without “public association,” Thelwall warned, there would be “private cabals” (Natural Right 46). Without the ability to speak with a collective voice, individuals would brood “over thoughts they dare not utter” (Natural Right 46). When Thelwall used his lectures to rouse “a sluggish and insensate people” from a “drowsy stupor, creeping over the frozen nerve of misery,” then, he did not so much suggest that the materiality of the printed word educated people by acting on their bodies, but rather that the spoken word carried a material current that allowed electricity to move freely from body to body (Rights of Nature 391). As in his account of a 1795 political lecture where “every sentence darted from breast to breast with electric contagion” (qtd. in C. Thelwall 367), Thelwall represented his sentences as electric because they associated word to thought and speaker to listener. Like the electric fluid acting on the animal body, the electric word sustained vitality by catalyzing associations in the body politic. This vital transmission was only possible when people were allowed to come together in the same space to speak and to hear others speak.

As an orator, Thelwall intervened between his listeners’ perceptions and their wills in order to reform the associations of the state’s diseased body. As a teacher of elocution, he extended his reformist associationism. Far from being the dumb orator Crabbe mocked, Thelwall instead continued to encourage free speech and defeat antisociality. Antisociality, which could stem from “regret, repining melancholy, and dissatisfaction,” impeded reform because the “man who considers himself as an isolated individual . . . [becomes] barren to himself and injurious, or at least unproductive, to society” (Tribune 224-5). This antisociality, Thelwall claimed, was a by-product of “the selfish system” of an increasingly capitalist economy and was only exacerbated by the prohibition against public meetings (Tribune 224). Like those restricted from speaking because of governmental legislation, those with speech impediments suffered from “diseased associations” that hindered them from contributing to public discourse (Henry Cline 59). As Michael Scrivener has shown, for Thelwall, “mind is not individualistic but a product of ‘associated intellect’ within the public sphere” (181). Thus, once we understand Thelwall’s material model of mind, we see that ministering to the speech defects of others was a political act. As a teacher of elocution and as a political activist, Thelwall was pursuing a common end: strengthening the associations of the minds that inhabited, and created, the public sphere.