In tracing the transatlantic roots of historical authority and epistemology in his How to Write the History of the New World, Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra argues “the tradition that locates the ‘West’ somewhere adjacent to the North Atlantic is amusingly pompous” (10). Following his provocation, this essay traces the contested genealogies and hybrid origins of the panorama, the camera lucida, and the daguerreotype: a set of Romantic-era visual technologies frequently discussed as originating in European metropoles. “Camera Lucida Mexicana,” then, recasts the geneses and genealogies of these technologies as a process of transatlantic exchange oriented toward the New World and the south, in this case, Mexico.

In locating the history of Romantic technologies and visuality in the New World, and in the global south, I argue that this re-orientation undermines claims to them as agents of imperial dominance. Instead, I show how these technologies emerge as contested, ambiguous, and frequently defiant obstacles against the desires of their operators in an attempted visual conquest of Mexico in the first half of the nineteenth century.

My interest in visual technology’s destabilization of objectivity is indebted to the work of Lorraine J. Daston and Peter Galison, who argue that, in the second half of the nineteenth century, scientific discourse posited objectivity as dependent on mechanical technology. Daston and Galison find in the pursuit of “mechanical objectivity” an “insistent drive to repress the willful intervention of the artist-author, and to put in its stead a set of procedures that would, as it were, move nature to the page through a strict protocol, if not automatically” (121). Here, the modifier “mechanical” works to re-structure objectivity through changing conceptions of the interdependence of technology and operator, while emphasizing the role of optical devices in the quest for “images, machines, and illustrators [that] would not budge even to obey the scientist’s own misdirected will” (124).

I draw Daston and Galison’s argument backward to the end of the long eighteenth century, and from the desires of scientists to those of the explorers of the New World. Perhaps it is no accident that when Thomas Carlyle first publishes the term “visuality” in 1841, he does so the same year the daguerreotype makes landfall in Mexico, in the hands of explorers wishing to literally own Mexican history by photographically reproducing it. Writing that Dante’s Divine Comedy presents a narrative where “every compartment of it is worked out, with intense earnestness, into truth, into clear visuality” (149), Carlyle equates truth with the uninhibited gaze by compartmentalizing Dante’s poem. At the same time, in Mexico daguerreotypists seek to tame the unwieldy compartments of Daguerre’s bulky box in order to clearly and truthfully replicate the landscape and the constitution of the what Nicholas Mirzoeff defines as the “visual subject in colonial modernity” (“Ghostwriting” 241). Thus when Hal Foster first defines visuality as “sight as a social fact” (ix), this definition is in many ways indebted to the contested definitions of visuality in early nineteenth-century Mexico, where explorers’ desire for mechanical objectivity battled against the very devices wielded in its pursuit.

My goal, then, is to argue first that discussions of visual technologies should occupy primary importance in the history of the interrelationship between visuality and travel in the Romantic period. This argument necessitates locating the emergence of Romantic visualities in the global south. The case studies I present show how the desire for objectivity was articulated and contested through antiquarian Mexican travel narratives in the first half of the nineteenth century. I pay special attention to the roles of nascent visual technologies—the camera lucida, the panorama, and the daguerreotype—in the creation of those images. Specifically, I argue that while such technologies were deployed in pursuit of mechanical objectivity, they continually emerged as powerful agents with the ability to grapple with and defy the wishes those using them.

Prevailing scholarship on the place of aesthetic ideals in Romantic travel has tended to focus on shifting conceptions of objectivity and subjectivity in tandem with shifting ideals of the place of the viewer, and the visual subject.

While this remains my goal here, I place visual technologies at the center of this shift. Ron Broglio shares my focus in this regard: in his Technologies of the Picturesque, Broglio argues that Romantic-era visual technologies dramatically changed the cultural relationship to visuality without being noticed. While I also place technologies at the center of this moment, the technologies I reference here did the opposite: they were noticed, lauded, and grappled with precisely because they did not, as Broglio argues, “help us master the landscape” and “further a sense of individual power over nature” (26).

In addition, scholarship on the importance of visual technologies generally focuses on its relation to the rise of photography, rather than an explicit engagement with their role in practices of travel and exploration. For example, Geoffrey Batchen and Jonathan Crary both cite the importance of the camera obscura leading up to the advent of the daguerreotype in the late 1830s (Batchen; Crary 78). My account of Romantic travel also gives a privileged position to the daguerreotype, but in relation to the camera lucida, a device not discussed by Batchen, Crary, or Stafford, and one that even in nineteenth-century use figured as a decidedly domestic and amateur apparatus rather than a device used by professional artists in the context of exploration in foreign lands (Hammond and Austin 54; Lee 63). I present the daguerreotype as a major point of conflict and contrast to the camera lucida, even as travelers desired that the production of objective images would be facilitated by both apparatuses.

As explorers and travelers produce images of Mexico that circulate on both sides of the Atlantic in the early nineteenth century, they continue to walk the fine line between the desired mechanical objectivity of the nineteenth century and picturesque vision that dominates discourses of the late eighteenth. I begin with the cases of Pedro José Márquez (1741-1820), a Mexican Jesuit priest working in Rome in 1804, and German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), who publishes his views of Mexico in Paris in 1816. I move on to the way the camera lucida emerges (in the hands of Scottish artist and architect Frederick Catherwood [1799-1854] in the Mediterranean and Mexico, with the support of English entrepreneur Robert Burford [1791-1861]) as an important instrument through which to join the ideals of the Romantic landscape with the desire for objective scientific accuracy achieved by the use of visual technologies. Burford’s panoramas, then major attractions in London, rely directly on Catherwood’s camera lucida-aided drawings as prototypes for panoramic images. Yet Catherwood’s relationship to the camera lucida is in doubt, as its supposed ability to re-create the objective world is disrupted during his work with John Lloyd Stephens (1805-1852) in the Yucatán between 1839 and 1841. This tension leads directly to the pair’s use of the daguerreotype on their second trip to Mexico. Originally viewed by Stephens and Catherwood as a tool to expedite their goal of presenting an objective visual account of Mexican antiquities and landscape, the daguerreotype emerges as a stubborn, defiant apparatus in contrast to its desired results. I conclude with a consideration of the daguerreotype’s new roles in Mexico, and how Stephens and Catherwood’s initial uses of the daguerreotype further complicate its relationship to the camera lucida and to later photographic practices in the Americas.

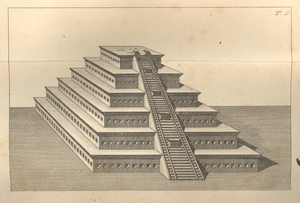

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, criollos (creoles) in the Viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru begin to assert their autonomy in opposition to the Spanish crown, giving birth to independence movements throughout the Americas that, by the 1820s, leave Spain almost devoid of American territory. Spain’s isolationist colonial policies—a major cause of the nascent independence movements—also mean a restriction on foreign travelers in the Americas. As such, almost no drawn-from-life images of American natural history or archaeology are produced prior to the 1820s, with two notable exceptions: Pedro José Márquez and Alexander von Humboldt. Márquez publishes Due antichi monumenti di architectura messicana (“Two Ancient Monuments of Mexican Architecture”), in Rome in 1804. Due antichi marks the first time Mexican archaeological images are produced in Europe, and even more significantly, they are images Márquezadapts from the work of José Antonio Alzate y Ramírez (1737-1799), a Mexican polymath and prolific author. Thus, Ramírez’s groundbreaking research on Mexican archaeology is first seen by a European audience as a result of Márquez’s work. Márquez’s presence in Rome is the ironic result of a July 1773 decree by Pope Clement XIV suppressing the Jesuit order, an order applied unevenly around the Catholic world but harshly in New Spain (Roehner 167). That year, Márquez is forced to leave Mexico and enter into a city with a long antiquarian tradition as well as, in his opinion, a long history of misrepresentations of Mexico (Cañizares-Esguerra 254-255). Due antichi responds to both of these problems. In the text, Márquez makes a passionate argument for the cultural advancement and complexity of the civilizations of Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, implicitly tying them to the civilizations of Egypt, Greece, Rome, and Babylon which function as the basis of antiquarian travel images. Márquez’s illustrations reinforce this point. In the untitled first plate from Due antichi, an engraving of the Pyramid of El Tajín (in modern-day Veracruz state) shows a highly schematized, geometric structure absent of any background context (Figure 1). What would have been a foliage-covered and largely unexcavated pyramid in 1804, Márquez renders as a flawless work of architectural precision. The pyramid’s six levels, each with identical rows of window openings and level roofs, mimic each other in proportional size and shape. The pyramid inhabits a nearly two-dimensional landscape where spatial depth is shown only through incised lines and the hint of a shadow at the pyramid’s right side. This rendering of the pyramid’s sharp angles, the precision of the stairway, windows, and level steps are deliberate attempts by Márquez to connote a degree of Mexican technological advancement tied to ancient Greek or Egyptian monumental structures. In short, in removing the structure from Mexico, Márquez seeks to place the pyramid in the most familiar context: the cultural sophistication of the ancient Mediterranean.

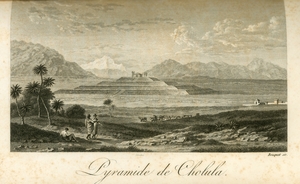

When contrasted with Márquez’s work in Rome, Humboldt’s contemporary images of Mexico open up a space to theorize the relationships between picturesque vision, subjective experience, and the desire for scientific objectivity. Humboldt spends the year of 1803-1804 conducting archival research in Mexico City, at the tail end of his now-famous exploration of the Americas between 1799 and 1804. On one of his few excursions outside the city, Humboldt journeys to what is now Puebla state and produces one of his final images in the Americas, Pyramide de Cholula (Figure 2). In Humboldt’s rendering, the massive four-stepped pyramid, topped by a small chapel, rises gently from the valley floor, dwarfed by the mountains in the background. The mountains’ jagged edges and shallow slopes serve as a point of contrast and comparison to the pyramid, simultaneously positioning it as united with the picturesque landscape as it maintains evidence of human artifice. In the foreground, two men clad in matching hats and topcoats converse, while a shirtless figure sits on the path next to them, staring into the ground. The figures’ proximity to Humboldt’s careful rendering of native Mexican trees makes apparent the image’s dual concerns of Enlightenment traditions of encyclopedic representation, visual legibility, and visualities during the Romantic period, particularly that of the picturesque landscape. This tension is especially apparent in Mexico, since Humboldt’s illustration of the Pyramid of Cholula represents such a marked contrast with Márquez’s contemporary work.

When Humboldt returns to Europe and publishes Pyramide de Cholula in his Vues des Cordillères (1816), it marks the moment for the genesis of an emerging visual dialogue in the Atlantic world vis-à-vis Mexico between the production of faithful representations of Mexican archaeology and geography, and the visual production of Romantic aesthetics in tandem with nascent visual technologies. This distinction and flux follows Nigel Leask’s elaborated tension between “subjectivist and objectivist strategies of representation” (167), which emerge as continually in flux and counterbalance in Humboldt’s work. In this way, Humboldt’s objective-subjective tension espouses a worldview where “the way we feel about the external world is as much a part of its meaning as what we can measure or know about it” (Leask 166). Cholula is an excellent example: Humboldt’s concern with presenting an encyclopedic inventory of the flora and geological landscape surrounding the pyramid speak to his desire to present the “beauty of the landscape” as a direct aspect of its scientific recording, both of which could be seen as mutually reinforcing in a “human-scale” (Godlewska 247) landscape view. Humboldt’s and Márquez’s work emphasizes the centrality of the Mexican imaginary in the construction of Romantic Atlantic visual genealogies. Their images are, especially in Márquez’s case, an encounter between Mexican visual concerns and the visual iconography of Mediterranean archaeological illustrations. Thus, their work sows the seeds for further contested visualities in Mexico following independence, as European and American travelers use, adapt, and grapple with Romantic-era visual technologies (the camera lucida, the panorama, and the daguerreotype) in relation to the aforementioned discourse exemplified by Márquez and Humboldt.

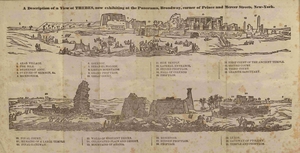

When New Spain gains its independence and splits into Mexico and the Federal Republic of Central America in 1823, suddenly Europeans and Americans are free to explore the region. Mexico occupies an unstable position in a post-independence world. Released from the Spanish crown, Mexico remains outside the linear historical narrative of the North Atlantic West. Its pre-conquest civilizations are an “historical tabula rasa” (Evans 2), ready to be mapped onto a larger transatlantic cultural geography. In this context, the Mexican landscape works to construct the illusion of totalizing, panoramic experiences for the citizens of the European metropole—in this case, London. Panoramas of Mexico originate from the interactions of two British citizens: William Bullock (c. 1773–1849), an English explorer and naturalist, and Robert Burford, owner and proprietor of the most popular panoramas in London. In 1822, Bullock travels to Mexico for six months, moving through Veracruz, Xalapa, Pulque, Puebla, Cholula, and Mexico City. Bullock uses his journey to write observations for his Six Months Residence and Travel in Mexico (1825), and to collect artifacts, documents, and illustrations for use in his exhibition Modern Mexico (1824), shown at the Egyptian Hall in London. Fittingly, the frontispiece to Six Months Residence is a panoramic landscape vista entitled View of the City and the Valley of Mexico, from Tacubaya (Figure 3). The print, displaying a rolling central valley floor, distant cragged mountains, and encyclopedic representation of Mexican flora, presents many of the same interests as Humboldt’s Pyramide de Cholula. But Bullock expands what was previously a squared-off view into one that encircles the viewer’s visual field, tying the spectator into the panoramic vista. The dramatic effect delimits the space available to exploration as it opens the boundaries of that exploration to the edges of the mountains, a possibility that was limited through Humboldt’s illustration.

When Burford receives Bullock’s print, he immediately makes plans to convert the image into a large-scale panoramic painting and exhibit it in the Leicester Square Panorama in London (Burford and Bullock). By 1820, as European audiences’ desire for more exotic spectacles grows stronger, and Burford begins incorporating the works of other artists from more distant locales. This is by no means unique to Burford: panorama owners frequently declare panoramic exhibitions as a safe and inexpensive alternative to international travel (Thomas 17). Bullock’s Mexico City panorama is one of many Burford exhibits during the early 1820s, from places as distant as New Zealand, India, the Arctic, and the Levant (Hyde). James Chandler and Kevin Gilmartin discuss the genesis and role of the panorama (both as a public exhibition and a visual system) originating from London and exported, in tandem with the conception of the modern metropolis, to other cities (7-10). At the same time, exotic locales in general, and Mexico in particular, are central to the formation of the panorama, and thus also to the cosmopolitan Londoner whose subjectivity was implicated in the panoramic view. As the origin of the panoramic view, London adapts and exports Mexico as a panoramic landscape, and thus as a visual mode to be applied to other locales (Chandler and Gilmartin 7). As the panoramic view is exported from London, it is adapted in two ways: first, to the aforementioned relations between objectivist and subjectivist modes of vision during the Romantic period, but second, it is problematized and disrupted in tandem with other visual technologies of exploration—most specifically, the camera lucida.

Daston and Galison note that the camera lucida was one of the primary devices used in pursuit of mechanical objectivity (119). An artist’s drawing tool consisting of a bent lens attached to a metal pole, the device had been theorized in scientific texts as early as 1611, but was only re-invented and manufactured on a large scale beginning in the early nineteenth century. The camera lucida’s bifocal prism allowed the artist to look through the glass and see an external image reflected on drawing paper. The camera lucida’s association with scientific mechanical objectivity belies its original target audience: amateur artists and domestic users who could take advantage of the device’s low cost and supposed ease of use. As a result, the camera lucida gains wide popularity after its invention in 1807, but strangely, it occupies a marginalized position in the history of nineteenth-century visual practice. Jonathan Crary’s foundational Techniques of the Observer, for example, never mentions the camera lucida. Celia Lury notes this gap in Crary’s account, suggesting that the camera lucida is an equal participant in the new mode of visual primacy, but only as an “archaic artisanal practice” (Lury 158). Yet in his seminal treatise on photography, Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes declares it “a mistake to associate photography, by means of its technical origins, with the [. . .] camera obscura. It is the camera lucida [. . .]” (106). Barthes’ idea will emerge as central to my argument later; for now, note the privileged position of the camera obscura in the contemporary history of nineteenth-century visual practice, particularly in relation to photography. Most discussions of the camera lucida situate it as an antecedent to early photographic practices (as opposed to a distinct visual system that impacts photography on multiple levels) and/or as a domestic visual tool for aspiring artists or scientists. But these two conclusions greatly underestimate the tool’s use and importance in Romantic travel and archaeology.

The work of Frederick Catherwood provides the best case study for the importance of the camera lucida. It is in his hands in Mexico that the camera lucida emerges, like the panorama and the daguerreotype, as an at once faithful tool and disobedient employee. Catherwood’s use of the camera lucida upends the established chronology of camera lucida to photography while illustrating the device’s contested genealogies and associations with purely scientific or domestic use in the European metropole. In 1836, Catherwood returns home to Britain after an eight-year stay in Egypt and the Levant, and he quickly gains a reputation as one of the finest archaeological travel artists in Europe. Catherwood is one of the first professionals to use the camera lucida in his work, some thirty years after the device’s invention (Hammond and Austin 3). The images produced on his travels, which include large-scale drawings and true-to-life schematics of archaeological sites through the Near East, are all rendered with the aid of a camera lucida. In fact, Catherwood’s fame rests partly on his ability to produce accurate recordings, an ability accentuated by the assistance of the camera lucida in his work (Bourbon 26).

The amount of experience and personal skill required to master the device undermines potential claims to the camera lucida as either a domestic or amateur instrument. An 1809 editorial by R.B. Bate, published in the London-based Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, and the Arts, speaks to the camera lucida’s usefulness for more advanced artists like Catherwood. After a six page delineation of the difficulty of working with the camera lucida, including discussing the proper placement of the prism, proper posture to allow for effective transverse eye movement, and the correct angle at which to tighten the drawing paper, Bate notes how the camera lucida will benefit advanced artists as they will ‘Find a great economy of time, upon extensive and complicated subjects in particular, by using the instrument in determining the situation of so many points as he may deem important; and which the camera lucida is allowed to give ‘with perfect truth and correctness of perspective.’ [. . .] [T]he truth of the reflected image in every circumstance give the camera lucida a decided superiority over all other known contrivances for the same purpose. (Bate 149-150)’ This bears repeating: “with perfect truth and correctness of perspective.” Anticipating Carlyle’s declaration of “truth and clarity,” Bate espouses the camera lucida as an effective weapon in the pursuit of mechanical objectivity. The camera lucida’s ability to re-create the world-as-image today marks the political stakes of contemporary visuality: defined as the system through which, as Nicholas Mirzoeff describes, visual subjects and representations are made to seem natural and ordered (The Right to Look 3).

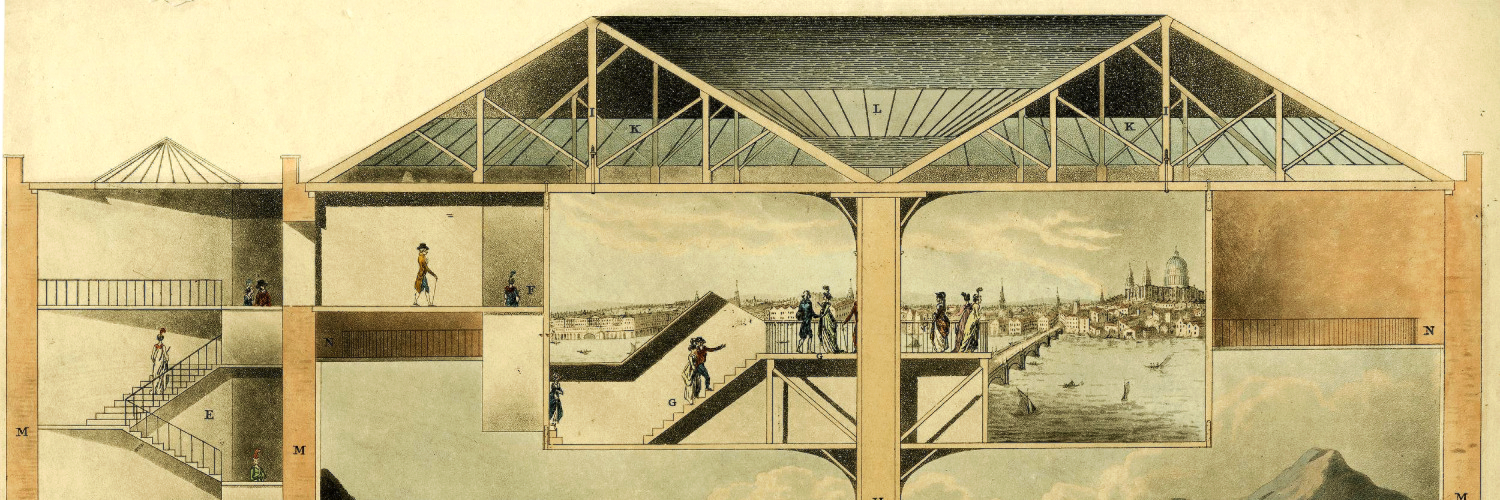

While in London in 1836, Burford invites Catherwood to construct a panorama of the city of Jerusalem, entitled View of the City of Jerusalem, based on Catherwood’s camera lucida drawings of the city. Catherwood himself paints the details of the image (Bourbon 31). John Lloyd Stephens, in London at the time, is immediately taken with Catherwood’s panorama (Bourbon 37). Burford sets up a meeting between Catherwood and Stephens, which would be the beginning of a lifelong friendship eventually resulting in the first scientific explorations of Central America. For Robert Burford, the meeting has a more practical entrepreneurial aspect: Burford encourages Catherwood (an architect by trade) to go with Stephens back to New York and open up his own panorama that can be used to exhibit Catherwood’s and Burford’s drawings (Comment 56). In 1838, Catherwood travels to New York with Stephens and opens the Catherwood Panorama at the corner of Prince and Mercer Streets in Manhattan. That panorama’s founding comes about as a result of personal exchanges from men on both sides of the ocean. Its global variation of exhibited scenes are intended as substitutes for world travel for an emerging American metropolitan population; in turn, those images are the result of transatlantic movements of visual technologies. Here, the visual discourses that define their formal elements remain part of an ongoing negotiation of visual concerns set in motion by Márquez thirty-four years before in Mexico. At this point, then, discourses of Romantic visuality articulated through visual technologies remain unstable in both form and content, while oriented both transatlantically and toward the south.

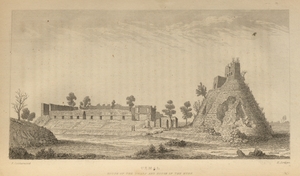

The grand opening of the panorama with View of Jerusalem is a great success. Catherwood’s 1838 advertisement provides a glimpse: “Splendid Panorama of Jerusalem, a painting of the largest class, 10,000 square feet, from drawings of Mr. Catherwood, brilliantly illuminated every evening by upwards of 200 gas-lights, admission 25 cents.” On June 23, The New Yorker publishes a rave review of the painting: ‘The most splendid panorama ever exhibited in this country [. . .] the painting of Jerusalem is a masterly production and conveys as perfect an idea of that memorable city as could be acquired by looking upon the real scene[. . .] After gazing for a few moments the illusion becomes complete, and you imagine yourself perched upon the governor’s terrace and looking down upon the narrow streets and massive walls beneath[. . .] [This] reflects great credit upon the taste and enterprise of Mr. Catherwood the proprietor. (“The New Panorama”)’ Here, what appears as a seamless marriage between the camera lucida and the panorama constitutes the eager American crowds as participants in the visual conquest of Jerusalem: travel is now unnecessary since the “ideal” Jerusalem already exists in New York. For such an experience, the crowds poured in. Later Catherwood and Stephens show three more of Burford’s canvases: Niagara Falls; Lima; and most notably View of the Great Temple of Karnak, and the surrounding city of Thebes, based on Catherwood’s own drawings from Egypt. No panorama canvases survive to the present day, but one can reconstruct some of this massive painting’s visual impact by examining the illustration in its accompanying guidebook (Figure 4). It is clear that during his time in Egypt, Catherwood has no intention of creating panoramas for large-scale exhibition. In Karnak, Catherwood’s attention for detail rendering the Karnak temple’s architectural features merges with views of the receding Sahara desert, here populated with scores of travelers and local Egyptians re-created from Catherwood’s drawings. Thus, the tension between panorama and camera lucida, born from competing visual concerns among artists, archaeologists, and entrepreneurs in Europe and the Near East now appears in the emerging international metropolis of New York. But the next year, Catherwood’s unique perspectives would grapple with yet another new context: Mexico. There, with Stephens, Catherwood’s artistic production in pursuit of mechanical objectivity invites another device, one that generates an uneasy relationship with his camera lucida: the daguerreotype.

When Stephens is appointed Special Ambassador to the Federal Republic of Central America in 1839, he uses the opportunity to conduct the first systematic exploration of Maya archaeological sites, with Catherwood as his chief artist. Mexico remains an historical tabula rasa for Stephens, and one he wants to inscribe with the United States’ national and historical imaginary. Stephens supposes that modern Mexicans are incapable of preserving Mexican archaeological sites, and remain disconnected from the cultures that produced them. He consistently refers to the areas south of the United States as “American” and “our country;” terms which serve to bring the Mexican material past into United States custodianship (Evans 58). As such, Stephens’ goal, with Catherwood at his side, is to utilize objective recording of the landscape to produce as many true-to-life visual representations of Mexican sites as possible, and in so doing claim them for the United States’ national consciousness. Stephens’ and Catherwood’s ability to reproduce that which they saw functioned as a visual conquest to bring the pieces to the United States, if only through the politics of display. For Stephens, as for the panorama’s visitors, there is no distinction between accurate representation and ownership. While utilizing Catherwood’s skill to reproduce Maya sites, Stephens plans to purchase and transport the entire Maya city of Copán to a “great museum of national museum of American antiquities” (Incidents of Travel in Central America 1: 115) as a permanent exhibit. The extent to which Stephens would ultimately pursue this goal—giving up only in light of massive transportation costs and impractical logistics—speaks directly to the correlation between accurate, reproducible visual representation and physical ownerships of the objects Stephens and Catherwood seek to represent (Patterson 25).

Together, Stephens and Catherwood conduct two different expeditions to Mexico, resulting in the publication of Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841) and Incidents of Travel in Yucatan (1843). In addition to being travel narratives, both books recount how the camera lucida and the daguerreotype repeatedly rebel against the desires of their operator, thus ironically rendering visible the unavoidable presence of the artist in pursuit of the mechanically-reproduced view. In Mexico, Catherwood’s use of the camera lucida begins to frustrate him as he finds Maya iconographic designs more complex than what he was accustomed to on his previous travels, and so too complex for the naked eye. Catherwood produces a number of iconographic studies of Maya works, particularly of memorial stelae (Figure 5), and the intricate iconographic programs that accompany them. In Incidents of Travel in Central America, Stephens notes ‘[T]he designs were so intricate and complicated, the subjects so entirely new and unintelligible, that [Mr. Catherwood] had great difficulty in drawing [. . .] He had made several attempts, both with the camera lucida and without, but failed to satisfy himself or even me [. . .] The “idol” seemed to defy his art (1: 120).’ Thus, at the moment when Stephens and Catherwood have gained international recognition for their ability to transport viewers through perfectly reproduced images, here both the instrument of mechanical objectivity—the camera lucida—and the landscape itself defy their pursuits and render visible their own presence and the failed promises of their pursuit. For Catherwood, the Maya world requires extended meditation on his place as an artist, whereas previously it was his ability to render his own presence invisible in his work that gained him such fame. The instrument that had previously been his trustworthy partner now abandons him. Following the publication of Incidents of Travel in Central America, Catherwood and Stephens return to Mexico in 1841 armed with what they hope is a device to again render the landscape perfectly, what Stephens refers to as “the daguerreotype apparatus.”

Daguerre’s invention, formally announced by the French government in January 1839, leads to other inventors claiming similar devices, which only serves to further fuel the invention’s popularity (Batchen 34). News and use of the device spreads so quickly that in their first expedition of October 1839, Stephens states his regret at neglecting to secure a daguerreotype apparatus for their journey, particularly since he had sponsored the first open public demonstration of the instrument in New York (Newhall 73). Only eighteen months later, Stephens and Catherwood are packing up the boxy instrument and transporting it to the Yucatán peninsula for their second Maya expedition. Just as prevailing historiographies of photography posit an evolution from the camera obscura and camera lucida to photography, Catherwood too hoped Daguerre’s machine would solve the problems they encountered with the camera lucida. Yet in continued defiance, Stephens and Catherwood encounter myriad difficulties with their new instrument. Incidents of Travel in Yucatan is filled with frustrated descriptions of the device’s bulkiness, failures, and finicky nature. Their first time using the device, Stephens relates how ‘[. . .] [T]he process was so complicated, and its success depended upon such a variety of minute circumstances, it seemed really wonderful that it ever turned out well. The plate might not be good, or not well cleaned; or the chemicals might not be of the best; or the plate might be left too long in the iodine box, or taken out too soon; or left too long in the bromine box, or taken out too soon; or a ray of light might strike it on putting it into the camera or taking it out; or it might be left too long in the camera or taken out too soon; and even though all these processes were right and regular, there might be some other fault or omission which we were not aware of; besides which, climate and atmosphere had great influence, and might render all to no avail (1: 103-104).’ Here, even acknowledging the extent to which its success depended on a variety of technological and personal factors, it is Stephens’ bafflement at the “climate and atmosphere” of Central America that stand out. Though Stephens and Catherwood are armed with a supposedly objective, rationalizing, scientific instrument, it is the landscape itself that rebels against their efforts at visual conquest. As Stephens’ attempted conquest depends on the production of a clear, mechanically-objective view, the daguerreotype fails to deliver: even when the image came out correctly, the detail was nowhere near what could be captured with a camera lucida. In short, the daguerreotype’s immediate fame and supposed technological advancement over earlier techniques matters little in this new context. The final straw for the daguerreotype’s use among the Maya ruins comes when Stephens and Catherwood are finally able to finish the daguerreotype process successfully. Even if everything goes well during the production of the image, the quality is such to dissatisfy Catherwood and Stephens. During the recording of buildings at Uxmal, ‘Mr. Catherwood began taking views; but the results were not sufficiently perfect to suit his ideas [. . .] They gave a general idea of the character of the buildings, but would not do to put into the hands of the engraver without copying the views on paper, which would require more labor than that of making at once complete original drawings. He therefore completed everything with his pencil and camera lucida (1: 175).’ Catherwood’s images of the buildings at Uxmal (Figure 6), while showing their “character” through the daguerreotype, cannot be accurately rendered to Catherwood’s preference. This is an unstable and crucial moment in the history of objectivity and the modern visual subject. Less than two years after its invention, in Mexico the daguerreotype emerges as an ambivalent and defiant instrument, and occupying an ambiguous position in relation to the camera lucida. When fine detail cannot be reproduced in a daguerreotype, Catherwood substitutes it for his own camera lucida; a device which, less than two years prior, he found similarly insufficient for producing records of Maya imagery. Here, Catherwood’s preference for the camera lucida is evidence for the destabilization of the camera lucida / photography progression, at least in the early years of the apparatus. At the same time, both devices function as mutually reinforcing and interchangeable, each one used in different contexts for different reasons. Only a short time into their trip, the pragmatic pair cease with the daguerreotype for archaeological illustrations altogether, using only the camera lucida. But they do not abandon the device: the pair set up a makeshift studio in Mérida, which is quickly converted into a local portrait studio once word of the machine spreads through the city. Suddenly, the daguerreotype—so inappropriate and ill-fitted to the scientific recording of archaeological sites—is perfectly suited to producing images of people.

It is in this small studio in 1841 that the visual interests of Stephens’ and Catherwood’s exhibition takes a sharp turn away from a pursuit of objective scientific accuracy, as they begin a short career as “ladies' Daguerreotype portrait takers” (Incidents of Travel in Yucatan 1: 100). The first daguerreotypes produced in the Americas specifically for exhibition (Stephens will display many of the images from his studio at the Catherwood Panorama in New York) present both subjects and ideologies completely removed from Stephens’ original motivation for the trip. This moment in the visual history of the Americas, caught amidst Stephen’s imperial project and the daguerreotype-mania that will spread across the continent in less than a decade, marks the emergence of a long nineteenth-century history of the use of photography in the formulation of personal subjectivities, identities, and discourses of (scientific) racism. In Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, Stephens takes great care to recount in detail some of the first people to sit for daguerreotype portraits, all of them women: ‘The young ladies were dressed in their prettiest costume, with earrings and chains, and their hair adorned with flowers. All were pretty, and one was much more pretty; not in the style of the Spanish beauty, with dark eyes and hair, but a delicate and dangerous blonde, simple, natural and unaffected, beautiful without knowing it, and really because she could not help it. Her name, too, was poetry itself (1: 101).’ Stephens never reveals the name of the “delicate and dangerous” woman, choosing only describe her as she sits for her portrait. It is telling and fortuitous that Stephens chooses to describe her in such detail. In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes notices the tendency to transform oneself in front of the camera, remarking how he would “make another body for myself, I transform myself in advance into an image” (10). Stephens describes this process in terms of the daguerreotype making the woman into an image of her bodily arrangement and costuming. He goes on to relay the difficulties encountered in this process: ‘Our first subject was the lady of the poetical name. It was necessary to hold a consultation upon her costume, whether the colors were pretty and such as would be brought out well or not; whether a scarf around the neck was advisable; whether the hair was well arranged, the rose becoming, and in the best position; then to change it, and consider the effect of the change, and to say and do many other things which may suggest themselves in the reader’s imagination, and all of which gave rise to many profound remarks in regard to artistical effect, and occupied much time [. . .] (1: 102-103).’ In detailing the woman’s appearance, ethnicity and her concern with the presentation of her own costume, Stephens alludes to what will emerge in the mid-nineteenth century as a prevailing discourse in daguerreotypy: the invention of personal subjectivities as a byproduct of photographic practice. Only two decades after Stephens and Catherwood’s trip to Mexico, Francis Galton (1822-1911), a British naturalist and polymath, uses composite fabrication of portrait photographs to create a series of racialized types in one of the first photographic attempts at visual eugenics (Sekula). In 1850, Louis Agassiz (1807-1873), doing for the United States what Galton did for Victorian audiences, produces a series of daguerreotypes of enslaved persons in Columbia, South Carolina, aimed at proving innate racial differences to support his theory of humanity’s polygenesis (Wallis). And in the 1860s, Agassiz produces a series of photographs of racial hybrids as undeveloped, tropical, degenerate bodies during a research expedition to Brazil, with the explicitly anti-Darwinian goal of proving racial differences as static, fixed, and climatically variable in line with his polygenetic theory (Stepan 85). Thus, the discourse of mechanical objectivity that here acts to accurately reproduce the individual subject is soon after taken up by scientists to mask their own presence in pursuit of an “objective” hierarchy of mankind.

While I argue that Stephens’ studio acts as a potential genesis for this discourse, there is no evidence that Stephens’ goal was to produce a classification or record of racial difference in the Yucatán. His intricate description of the dress of “the lady of the poetical name,” and the care with which her portrait was arranged, bears little evidence that a racial typology or desire to record was implicit in Stephens’ thinking. Moreover, it was Stephens himself who found the need to differentiate between an accurate, encyclopedic visual record of the archaeological sites he discovered in order to situate them inside American national consciousness; versus the people now living around them whom he characterized as less than able custodians. For whatever reason, Stephens did not emphasize this point by presenting visual evidence of U.S. and Mexican racial difference along which to construct a cultural hierarchy, much as Galton and Agassiz would do only a few decades later.

It is difficult to say more regarding Stephens and Catherwood’s photographs of the women of Mérida because the daguerreotypes no longer exist. When the pair returns from the Yucatán in 1842, they immediately set up an exhibition of their collected (or conquered) Maya artifacts, as well as their daguerreotypes, in the Catherwood Panorama. Catherwood’s rotunda, like most others at the time, was constructed of wood and met its end in an accidental fire on the night of July 31, 1842 (Barger and White 77). Upon seeing the ruins on the morning of August 1, Stephens writes in Incidents of Travel in Yucatan only that he “had the melancholy satisfaction of seeing their ashes exactly as the fire had left them” (1: 103). The loss is devastating on both sides of the Atlantic: Catherwood had neglected to take out insurance on his building, and Stephens on the artifacts inside, so both lose a great deal. Back in London, Burford—still hoping to create an international network for his panorama business—is forced to abandon his plans. And the modern record of the first daguerreotypes and camera lucida drawings produced in the Yucatán, as well as Catherwood’s panoramas, is destroyed.

Yet this loss may also provide insight into Stephens’ emotional infatuation with both his daguerreotype and the unnamed woman who sat for it. In Camera Lucida, Barthes describes in detail a photograph of his mother as a young woman, an image he refers to as the “Winter Garden Photograph.” He uses the image to posit the existence of two separate qualities inherent in every photograph: the “studium,” the photograph’s objective contents; and the “punctum,” that part of the photograph which impacts the viewer most forcefully, creating a subjective experience between viewer and image. Barthes recognizes the punctum of his mother’s presence for his own experience, and by extension the impossibility of a similar experience for any other viewer, so Barthes chooses not to reproduce the image: ‘I cannot reproduce for you the Winter Garden Photograph. It exists only for me. For you, it would be nothing but an indifferent picture, one of the thousand manifestations of the “ordinary”; it cannot in any way constitute the visible object of a science; it cannot establish an objectivity, in the positive sense of the term; at most it would interest your studium: period, clothes, photogeny; but in it, for you, no wound (73).’ It begs the question, given Stephens’ account of his visual and emotional infatuation with the daguerreotype of the unnamed woman, whether this image can “establish an objectivity.” Just like the “Winter Garden Photograph,” Stephens’ intimate experience with that image would have been accessible only to him, and hint as he may at his emotions, it is fitting that the photograph no longer exists. The image’s inaccessibility to, in Barthes’ terms, “science” and “objectivity” is insightful given Stephens’ presumed motivation for his and Catherwood’s mission to Mexico: the scientific, objective recording of Maya archaeological sites through the utilization of visual technologies created for the purpose. While, as mentioned previously, daguerreotypes would later be intertwined in a history of supposedly scientific, objective human typologizing, they function here as the final piece in a long line of foils to Stephens’ and Catherwood’s own insistence on the ability of the daguerreotype and the camera lucida to objectively record the art and archaeology of the Yucatán.

While daguerreotypes would later be intertwined in a history of human typologizing, they function here as the final piece in a long line of foils to Stephens’ own insistence on the ability to accurately record the world. As I have argued, the quest to accurately represent Mexican archaeological sites was a complex, multidirectional, and often highly contentious process whereby the definition of “accuracy” constantly adapted to new frameworks, locations, and visual technologies. While Márquez and Humboldt in many ways started this dialogue, Catherwood and Stephens brought it to its height with their use of the panorama, camera lucida, and daguerreotype in service of their goal of objectivity. Yet far from being their loyal servants, in the context of the Yucatán these technologies forced the pair to acknowledge the highly subjective nature of their task. The camera lucida continually fought with Catherwood in the Yucatán, forcing him to move to the daguerreotype, which in its own defiance moved Stephens toward an experience of total subjective personal infatuation in contrast to his own stated mission. And when this image is displayed, the wooden panorama gives way. Every device Stephens and Catherwood sought to use, from the camera lucida to the daguerreotype to the panorama, abandoned them. In the end, presented with the pile of ashes of all they had created, Stephens’ words take his concern with objectivity and hold on to it, but inside, without image or referent beyond emotional reaction: “I had the melancholy satisfaction of seeing their ashes exactly as the fire had left them.”

In presenting this series of contested technological genealogies and travel accounts, my goal has been twofold: to argue that visual technologies, long marginalized in discussions of Romantic travel, should occupy primary importance in that discourse; and second, that these technologies and their role in the evolving discourse of visuality emerges principally in areas located outside the historical West. The evidence for this was multifaceted. First, I showed that visual technologies act as mediators between desires to convey subjective experience versus objective knowledge and their presentation in visual media—an assertion that disrupts characterizations of linear evolutionary development in visual technologies during this period. For Catherwood, the use of the camera lucida is the culmination of a burgeoning intellectual exchange system that values scientifically accurate representation in tandem with Romantic picturesque aesthetics, both of which come together in Burford’s panoramas. And the daguerreotype, alternately viewed by Batchen and Crary as a descendant of the camera obscura or a device to supplant the camera lucida, here functions simultaneously as inadequate for mechanical objectivity and valuable enough to produce images of subjective emotional power. But the meditative power given to these technologies led to my second point, that these technologies are powerful agents that render visible the artifice of both mechanical objectivity and visuality. Catherwood’s frustrations with the camera lucida in Mexico, Stephens’ characterizations of the perils of daguerreotypy, and the pair’s adaptation of the daguerreotype to a new context all speak to this. Finally, I sought to illustrate the inability of a center/periphery model of cultural and intellectual diffusion to account for the proliferation of images of Mexican history and archaeology in the Atlantic world during the early nineteenth century. Though all these technologies were “invented” in Europe, this fixation on geographic origin belies a transatlantic and southern-oriented genesis for the constitution and construction of visual technologies, Romantic visualities, objectivity, and the rise of the visual subject.

Works Cited

List of Figures