Unheard melodies

“When I put my ear to the page, I hear nothing but the sound of my hair against the surface. If I erase the letters, no “sound” remains. Sound is not on the page, even if a graphic transmission allows for its properties to be noted for reproduction’” (Johanna Drucker, in Marjorie Perloff and Craig Dworkin, eds. The Sound of Poetry/The Poetry of Sound, 2009, 239) [my emphasis].

“Sound is what happens in Lyric” (Jonathan Culler, Theory of the Lyric, Harvard, 2015) [my emphasis].

What does it mean for sound to happen in Lyric? Culler’s claim invites questions about how we define Lyric, but also about the phenomenology of sound, its medium, and the relation between sound, print and poem. How is sound experienced by the reader – by the eye, the ear, the mind’s ear, when it is read aloud and read in silence, in Lyric? The preposition “in” suggests that Lyric is a container for sound, a vessel, perhaps, an urn:

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheardAre sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d,Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: (John Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn” ll. 11-14)

Where is sound happening in Keats’ lines? On the page? In our ears? “through the air”? In our mind’s ears? Is there a difference between the way it “happens” in our ears, when read out loud, and in the mind’s ear, during silent reading? And what of the sounds that are seen but not heard? Like the playful eye-rhyme suggested by “unheard” and “endear’d:” both words contain the word “ear,” but we only hear it sounded in “endear’d.”

And what of the poem’s other silences? The gaps and pauses? The moments of no sound and “no tone”? The quiet? The silence at the end of a line after “unheard,” the white space, the line break? Or, somewhere else, as a boy “hangs/ waiting for the owls to answer”? What of these silences? Are they heard or “unheard”? What of the many silences contained in and articulated by Lyric? The silence of the urn, this “silent form”? Are they "happening" in the same way as sound ‘happens’? And what of those eye rhymes we see and don’t hear, between “heard” and “endear’d”? Both contain the word “ear,” but it is not sounded in “heard,” seen not heard, silent. And what is soft sound? In these lines, soft, in the phrase “soft pipes”, suggests a quality of sound - timbre and volume. But do we experience different qualities of sound, and degrees of softness and loudness, when we read these lines silently? How does quietness “happen” in a poem?

The word “volume” acquired an acoustic register in the late eighteenth-century, according to OED, a musical sense first recorded in Busby’s Complete dictionary of music (1786) referring to the tone and power of a human voice: “Volume, a word applied to the compass of a voice from grave to acute: also to its tone, or power: as when we say, ‘such a performer possesses an extensive or rich volume of voice’.” (OED, 9a). The first recorded usage of the word volume as “Quantity, strength or power, combined mass, of sound” (OED, 9b) occurs a little later, in 1822, and is attributed to Lord Byron in Werner, (v.i. 134 I heard…, Distinct and keener far upon my ear Than the late cannon's 333) volume, this word—‘Werner!’). This new sense of the word registers a larger cultural and scientific curiosity about the nature and experience of sound in the period, a curiosity which also finds shape in poetry of the period.

The contemporary poet Alice Oswald is also interested in the expression of volume, and plays with different ways of suggesting quiet and silence through and around words, using space, measuring lines and fading ink to create a graphic code for calibrating sound and silence. In the last lines of her poem "Tithonus" (Falling Awake, 2016, 45-81), for example, there’s a moment of graphic quietening. The final letters of the poem fade into whiteness, so that the poem’s concluding word, “appearing” is almost invisible, printed in the very lightest shade of type, as dawn, and light, appear.

The fading font produces an aural effect, the suggestion of diminuendo, in the way that bold or CAPITAL LETTERS, larger font size or italics can suggest a louder volume. But, as we shall see, a poem can sound or produce the effect of quiet in other ways.

Coleridge, too, was intensely curious about the nature and experience of sound in the ear and in print. “Frost at Midnight”, written in Somerset in the winter of 1798, does not use the word “volume”, but records a playful exploration of dynamics and of the various ways (graphic, rhythmic, linguistic and as an effect of tempo) in which sound and quiet could be represented to both eye and ear in a poem. Like other Romantic poets, Coleridge was fascinated by visual codes and patterns for sound and marking emphasis. Julia S. Carlson has shown how Wordsworth drew on developments in cartography and rhetoric in his own shapings in and of sound on the page (Julia S. Carlson, Romantic Marks and Measures: Wordsworth’s Poetry in Fields of Print, 2016). Taking this yet further, I suggest that Coleridge was also preoccupied with how to represent sounds and especially volume, and that his imaginative interest in acoustics and in musical forms and notation informed the way he shaped sound into both aural patterns and visual language in his poetry.

ii. pp

Many of our critical terms for discussing lyric poetry are, of course, borrowed from music; for example, as Susan Stewart has explained: “we speak of such features as counterpoint, harmony, syncopation, stress, duration, and timbre” as some of the “ways in which sound is measured as if music and lyric were analogous” (Stewart, 2002: 68). In music, however, there is a system of notation for marking dynamics on a musical score, differences in volume and also in the quality of the sound, pp, f, piu p, poco a poco dim., molto piano and quasi niente, for example. The Romantic period witnessed the expansion of the range of musical notation marks for dynamics; for example, it was during the last decade of the eighteenth century, “that the convention of indicating a gradual increase or decrease of volume by terms such as ‘cresc’ or ‘dim.’, or by ‘hairpins’, became commonplace” (Clive Brown, 1999: 62).

The expressive possibilities of volume became increasingly important to composers and performers in this period. In part, this was enabled by developments and innovations in musical instruments themselves: the pianoforte, invented in the eighteenth century, allowed a much wider dynamic range than had been available to the harpsichord, for instance, and it was during the period 1750-1850 that various adjustments were made to stringed instruments which increased the range of volume they could express. Changes in the way sheet music was produced in the period may also have contributed to this interest in dynamics and its expression on the page as well as in performance: there was an increase in the publication of sheet music in the later eighteenth-century which meant, Brown argues, that the performance of music was no longer always in the direct acoustic control of the composer, since in the later period composers were no longer physically present to instruct performers how to alter dynamics. This is perhaps one reason why composers increasingly marked their scores to indicate these dynamic shifts. Moreover, “Many composers . . . came increasingly to regard accentuation and dynamic nuance as integral to the individuality of their conceptions and were unwilling to entrust this merely to the performer’s instinct” (62). For this reason, he suggests, during the nineteenth century there was “a proliferation of markings, designed to show finer grades or types of accents and dynamic effects, and performance instructions of all kinds were used ever more freely” (62). It is likely that it was a combination of factors to do with the production and performance of music as well as technological innovation in the dynamic range of instruments that led to the development and proliferation of dynamic notation in the period, and that this also registered a wider cultural interest in sound and its expression.

iii. Voicing and Volume

A range of new terms emerged for indicating the dynamics of performance in music but also in the fields of literary performance and rhetoric. It was not only on musical scores that dynamic markers appeared: a number of eighteenth-century literary critics also annotated reading texts to indicate volume and dynamics, the levels or the qualities of quiet or loudness for performance; some adopted musical notation, others used different terms. Discussing reading aloud, late eighteenth-century critics of rhetoric such as James Beattie associated different volumes with different emotional states and intensities of feeling and indicated in their annotations how readers might vary the volume and intensity of their voices to best express the affective range and qualities of a piece of writing. Varying the dynamics of reading, reciting or speaking, he explains, could also engage the listener and be more persuasive. In Dissertations Moral and Critical (1783), Beattie argues that: ‘In describing what is great, poets often employ sonorous language. This is suitable to the nature of human speech: for while we give utterance to that which elevates our imagination, we are apt to speak louder, and with greater solemnity, than at other times" (I, 629). The word “sonorous” here conveys a sense of volume as well as suggesting a particular style, meaning, “Of spoken or written style: using imposing language; having a full, rich sound; imposing, grand; harmonious” (OED, 3a). The first recorded instance of the word to describe language is recorded in 1650, and derives from an earlier usage of the word to mean, more generally, “That makes a loud or resonant sound; capable of producing a loud sound, esp. of a deep or ringing character” (OED, 1a). The concept of linguistic volume Beattie’s comment suggests invites further investigation: certain words might be considered “sonorous”, others quiet depending, perhaps, on semantic associations, others because of onomatopoeia. The possibility that writers of the period considered the volume of words when selecting and composing a poem, for example, and that readers were attuned to the possibility of linguistic dynamics opens up another dimension for literary critics.

The concept of volume also shaped how Beattie understood the rhythm of a poem or piece of dramatic writing. Readers should, he points out, attend closely to the rhythm of the writing, and this, he explains, could be understood in terms of loudness as well as duration, “The rhythm of sounds may be marked by the distinction of loud and soft, as well as that of long and short” (I, 283). It’s clear from Beattie’s account that volume was part of a critical vocabulary for understanding rhythm and conversely, as we shall see, in poetry, rhythm can express sound dynamics and volume.

Beattie was also concerned with the dynamics of performance, that is to say with how passages should best be read aloud to convey their mood and affective dynamics, and volume was an important aspect of this. He explains, for instance, that “Words of indignation pronounced with a soft voice and a smile. . . would be ridiculous” (I, 241). When reading aloud, choosing the appropriate volume and modulating between degrees of loud and soft was considered essential to the successful performance of a poem.

In his Art of Speaking, for instance, James Burgh explained how a speaker’s success with his audience” depends much upon his “setting out in a proper key, and at a due pitch of loudness. If he begins in too high a tone, or sets out too loud, how is he afterwards to rise to a higher note, or swell his voice louder, as the more pathetic strains may require?” (emphasis original (12)). Burgh turns to terms such as “proper key,” “due pitch,” “tone” and “note”, which were firmly part of musical as well as rhetorical discourse. He draws on them again when describing how the different emotional states require different modes of expression in both facial features and gestures, but also in terms of the dynamics of voice. “Despair”, for instance requires the “tone of the voice” to be “loud and furious” (17). Whereas “Shame” requires a voice that is “weak and trembling” as well as short sentences and drawn down eyebrows to convey its full expression (17). He marks a number of speeches and texts with symbols to indicate the quality of delivery, which includes volume, for example in a speech on “Horrors of War,” an extract from Pope’s Homer. Certain lines, he indicates, are “to be spoken quick and loud,” others “to be spoken faintly, and with pity” or “to be spoken with a quivering voice” (16, 17). Recognising and performing the appropriate volume for particular literary passages when reading them aloud was key to their rhetorical expressiveness, and Burgh offered readers help in doing this by using descriptive language to indicate the appropriate dynamics. Other kinds of notation were also available.

In his Lectures on Elocution, Thomas Sheridan uses musical terms to distinguish between loud and soft, and high and low: “Loud and soft in speaking, is like the forte and piano in music, it only refers to the different degrees of force used in the same key whereas high and low imply a change of key” (83). Joshua Steele’s Prosodia rationalis: or, An essay towards establishing the melody and measure of speech, to be expressed and perpetuated by peculiar symbols stresses the importance of modulating the voice, and sets out symbols for accent and emphasis, loud and soft (24), which he applies to a number of literary examples, including a speech from Hamlet (40).

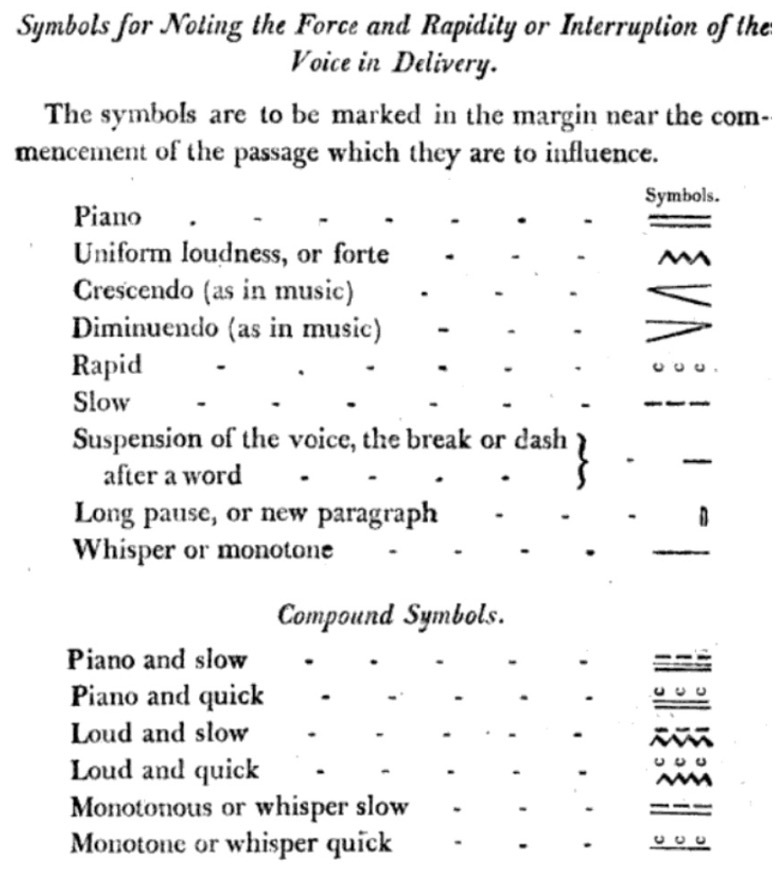

Gilbert Austin, writing in Chiromania, or a Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery, also uses symbols, including some musical notation such as the hairpin to indicate shifts in loudness as well as a number of other symbols, such as the zigzag line to indicate uniform loudness or forte, explained in “Symbols for Noting the Force and Rapidity or Interruption of the Voice in Delivery” (367). He advises readers and performers that these symbols were “to be marked in the margin near the commencement of the passage which they are to influence” (367).

Figure 1. Symbols for Noting the Force and Rapidity or Interruption of the Voice, Austin, Chiromania (1806).

It is important to note that this kind of notation was not usually deployed by poets themselves; it was added later to mark up a text for performance, to encourage emphasis for dramatic and rhetorical effect. There were perhaps stylistic cues in the writing itself which these notations and marginal indications were responding to and amplifying. It was not necessarily only the subject matter or emotional tone of a piece of writing that suggested a particular volume; it could also be an effect suggested in the rhythmic and linguistic texture of the poem itself. Lyric poetry has its own language and codes for communicating volume and dynamics, and these effects do not depend on performance or vocalisation, on the timbre and grain and pitch of a reader’s voice, but can be experienced even when we read a poem in silence. There are other ways that a poem might register and express shifts in volume, not just in performance, but also during silent reading. If onomatopoeia denotes a shared code or language to represent certain sounds, like a cat purring or a dog barking, what are the linguistic, formal and rhythmic codes and cues of quiet? Shhhh, hush, ellipses . . . what else?

iv. Silent reading

Coleridge was well known for reading his own poems aloud, and of course when a poem is voiced, the reader can vary the volume as well as the pitch and tone, but usually there is no direct verbal cue or instruction for this in the poem itself (as there sometimes is, say, in a play script, which often gives the actor or reader performance and stage directions). When he read his own poems aloud, Coleridge could of course vary the volume as he thought fitting. But how could he communicate the appropriate dynamics to his readers? And might they experience these shifts in volume during silent reading? Although, as Lucy Newlyn has shown, “the practice of ‘reading aloud’” was “a thriving one at the end of the eighteenth century” (355), so too was silent reading. Laura Mandell points out that Romantic poets expected their poems to be read in silence, and that despite Wordsworth’s “love of reading-and-writing aloud and performing his poetry, nonetheless Wordsworth knew that most would encounter it as silent and graphic. Blake, too, could not mistake the essential noiselessness of his prints” (220). She goes on to argue that “their poems thematised their own soundlessness while offering compensatory images”(220). And yet the poems, read in silence, are not, perhaps, entirely soundless.

Effects or impressions of sound and volume can be experienced when a poem is read in silence. There is also the possibility of an imagined listening. Lyric poems can have their own inscripted codes and cues for volume and dynamics, ways of suggesting and registering shifts between loud and soft, sound effects which we experience even when we read in silence. And these differences in volume are expressed or suggested in various ways, in and through rhythm, vocabulary and lineation. The question of what volume means in relation to a poem is worth exploring further. If, according to the Anthony Ashley Cooper, third Earl of Shaftesbury, certain colours were “quiet” (313), perhaps a poet could also produce effects of quiet or loudness in words, rhythms, and spatial patterns on the printed page. And this experience of sound puts pressure on the very idea of ‘silent reading’ itself.

The expansion of print, according to Walter Ong’s well-known thesis, produced a shift from oral reading aloud to quiet and then silent reading. Print, he claimed, was one factor in the creation of privacy in modern society, and, he argues, the production of books that were “smaller and more portable than those common in manuscript culture” set the stage “psychologically for solo reading in a quiet corner, and eventually for completely silent reading” (131). It should be noted that silent reading in the West long precedes the invention of print, and is recorded by 400 CE, in Augustine’s famous comments on Ambrose, archbishop of Milan, in Confessions 6.3.3. And that Ong’s description of print as a kind of silencing medium does not account for the various kinds of sound which print can embody. Perhaps, as Steven Connor suggests, “the move from sounded to silent reading” was not, "simply a move from noise to quiet. Rather, perhaps, it is a move from one kind of sound to another … The increasing commonness of silent reading is to be regarded therefore, not as the simple turning down of sound, but as the creation of a more complex space of inner resounding. (106, 109)" To push this further we might ask whether these “spaces of inner resounding” might vary according to genre. Perhaps Lyric enables and produces distinct kinds of aural and acoustic “spaces," distinct possibilities for inner resounding. We might ask whether Romantic lyric is quieter than other genres or sub-genres, than declamatory neoclassical lyric, say, or than epic or satire. Perhaps the intimate occasion of certain lyric poems itself implies a dynamic of performance, that they be read in a quieter voice than a poem in another genre. Lyric, I want to argue, invites a particular kind of listening, and in the Romantic period this listening was inflected by historical contingencies in musical notation, book publication, and reading practices. The way volume was heard, and indeed the volume of poetry was recognised and interpreted, changed in the Romantic period. And perhaps one reason for this was that during this period a historical juncture between oral and silent reading was especially significant and pronounced.

In Discourse Networks 1800/1900, Friedrich Kittler famously suggested that reading after 1800 was shaped, Steven Connor explains, by the “principle of what might be called oralized writing,” (128) what Connor calls a “consensual hallucination, namely the capacity for a kind of ‘earsight’ or ‘hearsight’ that allows one to mistake writing for voice, to imagine that writing is everywhere suffused with the most intimate and expressive accents of the voice” (129). But if print could express, silently, the accents of voice, it could also register the dynamics of voice, and descriptions of sound in the poem itself. Dynamics are a feature of accent, but accent is not the only way dynamics are expressed. A printed poem can also convey shifts between loud and soft on the page, for example, such as a gradual quietening. And such shifts are not only descriptive but can also be mimetic of what is described. They can register effects of intimacy and musical and rhetorical patterns of expression. The question of how a poem might register these shifts and gradations in and of sound took particular inflection and emphasis in the Romantic period not only because of shifting reading practices but also because of a growing curiosity about the developing science and technologies of sound transmission, such as the stethoscope and microphone, and, later in the nineteenth century the phonograph, telephone and telegraph, as well as a fascination with the ways in which sound was codified in music, writing and in other visual forms, such as Chladni figures, the Phonautograph and the Eidophone, all part of what Coleridge was to call the “embryo Science of Acoustics” (197).

v. Listening to Quiet

Coleridge was a great talker, musical, oracular, entrancing, and his eloquence has been rightly celebrated. At times, his talking could be challenging; he was not as sensitive perhaps as he might have been to his own listeners: Wordsworth could not understand “one syllable” of his friend’s oration despite listening attentively for two hours, according to Samuel Rogers’ report (308). There are many accounts of people listening to Coleridge, fewer of Coleridge himself as listener. And yet although he didn’t always attend enough to his listeners when he spoke, he could be an acute and sensitive listener: his poems, as well as his notebooks, are full of great moments of listening.

Throughout Coleridge’s writing we find traces of this sensitivity in his “records of attentive listening,” as John Hollander has termed them. And often the sounds which drew his ear were quiet sounds. In these lines from a notebook entry, for instance: "I hear only the Ticking of my Watch, in the Pen-place of my Writing Desk, & the far lower note of the noise of the Fire— perpetual, yet seeming uncertain/it is the low voice of silent quiet change, of Destruction doing its work by little & little."

This is a subtle pitch of listening: to distinguish between the clock and the lower note of the fire. ” Coleridge is drawing on a musical language, “low note”, to describe and distinguish between the sounds he hears. And he was curious about how these subtle variations of pitch and dynamics might be expressed in the texture of a poem.

Coleridge was writing on the cusp between reading aloud and silent reading. This is perhaps one reason that he was interested in the space between thought and address: in “Frost at Midnight,” for instance, he is addressing his babe, but in silence. This intimate occasion might also account for the poem’s interest in quiet sounds and sounding quiet. The volume of a poem perhaps depends on occasion as well as on genre, so that the intimate occasions of certain kinds of Romantic lyric poem might be productive of quiet, or at least be quieter than more declamatory or public modes. Like other Romantic poets Coleridge was thoughtful about the sound of poetry, and about shaping sound and silences—especially because he was writing in an age when poems were very often read in silence.

Writing in Victorian Studies, Laura Mandell offers a specific technological explanation for a shift in reading practices, arguing that “Eighteenth-century changes in printing practices facilitated silent, rather than vocalized, reading of poetry.” (220)

. She suggests that the typographical shift from the long "f"-like "s" to the “s”, for example, accompanied a shift from reading aloud to silent reading (the “f”-like “s” being associated with reading aloud). It’s interesting to note, as Mandell does, that in the 1798 edition of Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads, both forms of “s” are used, and this, she suggests, “would have complicated silent reading” (220). Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner, for instance, uses the “f” like “s,” and so calls for reading aloud. Mandell explains that this is because of different processes of reading associated with silent reading and reading aloud. You need to pronounce a word which contains an “f” like “s” to know whether it is an “f” or an “s,” she explains. But when an “s” form is used, you recognise it in a different way, which does not require pronouncing it or sounding it out. And yet, I would argue, this account of silent reading as a kind of visual decoding, a reading without sound, belies the complexity of the way sound operates and exists in the medium of print and in a poem.

Mandell’s notion of sound focusses on the idea of the voice and voicing; but poems offer other kinds of sounding and other patterns and articulations of sound. Coleridge understood poems to be musical forms, and his poems are full of accounts of other kinds of sound, which further complicate this distinction between silent or vocalised reading. Indeed, his poems seem to invite a play between eye and ear, not just by varying the typographic forms of letters such as the “s.” They invite us to think about the relation between seeing and hearing not only in terms of voice but also in terms of music and pattern.

Notwithstanding the need for further exploration of Mandell’s claim about the cognitive processes involved in reading aloud and reading silently, it is clear that poets writing in this period were keenly aware that reading practices were shifting, as Mandell and Newlyn have shown. It is also worth considering whether, and how, these and other cultural, technological and scientific changes might have shaped and influenced the representation of sound and dynamics in their poetry. Their poems invite further thinking about the semiotics of sound and of volume through a playful and dynamic interplay between eye and ear.

Writing elsewhere, Mandell examines Laurence Sterne’s play with visual and aural codes registered in his use of a sequence of four asterisks (****) to denote words which might offend readers in Tristram Shandy . The **** are difficult to voice, she explains, but the words they represent and obscure present a different challenge to those reading aloud to an audience; his use of **** thus engages with a shift in reading practices in a playful way, mindful that some would read the novel aloud, others in silence.

Coleridge’s engagement with the relation between sounds heard and seen or codified on a page, while not usually overtly humorous in this way, was often, as we shall see, no less witty.

vi. "O that I had the language of Music!"

Writing in his notebooks Coleridge expressed his frustration that he did not “have the language of music” (II: 2035). This could mean that he was unable to read a musical score, or that he did not feel he fully understood musical language. And yet perhaps he was being overly modest; he does, after all, analyse the prosody of Paradise Lost in terms of a pattern of “fifteen breves”, which suggests some knowledge of musical terms (Marginalia, iv. 603-4). And although there are no musical scores to be found in his notebooks, they do contain quite a few comments about his wide-ranging musical listening, to instruments such as the Eolian harp and Glass Harmonica as well as to a range of polite and popular musical forms; he notes, for instance, the superior song of the Ramsgate Muffin Man but also talks about enjoying Beethoven, Weber, Mozart and Cimarosa. In an essay in The Friend he identifies a sense of ‘recognition’ in listening to music: ‘If we listen to a Symphony of Cimarosa, the present strain still seems not only to recall, but almost to renew, some past movement, another and yet the same! Each present movement bringing back, as it were, and embodying the spirit of some melody that had gone before, anticipates and seems trying to overtake something that is to come (Notebooks ii. 2356).’ This sensitivity to the effects of musical repetition informs Coleridge’s own poetic composition and points to the importance of musical thinking to his own understanding of sound and its forms and effects in poetry.

Coleridge was keenly aware that poets did not use the “language of music” itself, and that included musical notation, to indicate the dynamics of a poem. And yet, as he instinctively understood, somehow certain poems or lines in poems can suggest different dynamic qualities, with some moments seeming louder or quieter than others. Coleridge’s poems are especially rich in dynamic effects. It is striking how many of his lyric ‘Conversation poems’ not only meditate on sounds heard, but themselves describe and also communicate changes in volume. Consider the following shifts: from the owlet’s cry which comes “loud” (l.3) to the quieter sound of the fluttering soot on the grate (l.15) in “Frost at Midnight;” from the silence of the stream (l.6) to the happy song of nightingales in “The Nightingale: A Conversation Poem;” from “green and silent spot” (l.1) and “small and silent dell” (l.2) to the crescendo in Invasion’s “thunder and the shout,/ And all the crash” (l.36-37) in “Fears in Solitude;” from “the stilly murmur of the distant Sea,” that “Tells us of Silence” (ll.11-12), to the music of the breeze as it plays over the lute strings in “The Eolian Harp” (l.15). Coleridge offers a descriptive vocabulary to describe a range of dynamics, a shifting scale of volume from loud to quiet to silence. But his poems not only name and describe these dynamics but also perform these shifts in their verbal, acoustic and rhythmic textures.

The late critic Thomas Macfarland was attuned to dynamic shifts across Coleridge’s poetry. The opening lines of “The Nightingale: A Conversation Poem,” he suggests, have, “a quietness that is in stark contrast to the frenetic notes of the hysterical sublime” we hear in some of Coleridge’s earlier work (246). The word “quieter” suggests intimate, less declamatory; but his choice of word also conveys a sense of volume. I want to push this yet further and think about how this sound, this quiet is expressed:

Distinguishes the West, no long thin slipOf sullen light, no obscure trembling hues.Come, we will rest on this old, mossy bridge!You see the glimmer of the stream beneath,But hear no murmuring: it flows silentlyO’er its soft bed of verdure. All is still,A balmy night! And tho’ the stars be dim,Yet let us think upon the vernal showersThat gladden the green earth, and we shall findA pleasure in the dimness of the stars.

How is a sense of quietness achieved in these lines? The language seems to be visual rather than aural here; the description begins by calling up to the eye what is not seen, clouds, a slip of light, trembling hues. The repetition of “no” emphasises, by contrast, the solidity of the deictic “this” in the phrase “this mossy bridge”, and the simple affirmation “You see” in the next line, emphasising what the eye can see. This visual language is soundless in one sense, anticipating the soundlessness described when we reach ‘no murmuring’ and ‘silently’. But the language takes on a more complex sensory register when we reach “dim”, a word used in these lines to describe a visual phenomena, faintness of light (OED 1 a), but which also had currency as an acoustic term in this period, meaning “Of sound, and esp. of the voice: Indistinct, faint” (OED, 5; curiously, the last citation in OED for this sense of the word is in the Romantic period, in Shelley’s 1817 poem “Marianne’s dream”). The lines create an effect of diminuendo in terms of visual description and also in sound, so that effects of eye and ear confirm and amplify one another. What else in the opening lines suggests quiet? That word “still” is important; it offers one way in to thinking about how a sense of quiet is expressed in these lines. The predominant meaning of “still” here is “motionless” (OED, 1). But for Coleridge’s first readers the word also had a sense relating to volume, “Of a voice, sounds, utterances: Subdued, soft, not loud (OED, 2a). This sense of “Still”, according to OED is no longer current. I think that this correspondence between movement and volume offers one way to think about how poetry expresses sound dynamics in and through shifts in movement, tempo or pace. It is, after all, moving or vibration of matter, as Coleridge understood, that creates sound in the first place as in the strings of a lute or an Eolian harp. That word “trembling”, in the phrase “trembling hues”, amplifies the sense I’m referring to here: overtly it’s referring to a visual phenomenon but it calls a sense of gentle movement to mind, the gentle movement of a stringed instrument playing very quietly (trembling suggests a faint movement).

There is something suggestive about using Coleridge’s use of the word “trembling” to describe colour, something synaesthetic perhaps, which calls to mind a kind of quiet sound by association. But which also alerts us to the sound texture of these lines and the way in which they move: the repetition suggests a kind of trembling and also a kind of quietening. In the opening of “The Nightingale. A Conversation Poem, April 1798”, the thick texture of repetition of the word “no” (ll.1, 2, 3, 6) which is drawn out by the o sound in “flows” (l.6) and “O’er” (l.7) creates a slowing effect, so that the sound is not modulating as freely as we might expect, not moving not progressing, and this slowing suggests a quietening.

Coleridge was interested in how gradations of sound were experienced by the listener and also by the reader, and he was thoughtful about how that might be represented on the page and in a poem. His poems are often intensely musical and sensitive to acoustic shiftings. Changes in linguistic register, tense, shifts in metre, pauses, punctuation marks, and the sonic texture of a line, the distribution of phonemes, all contribute to how a poem shifts dynamics between loud and soft. Pitch and tempo, genre, pacing and tonal register can contribute to a poem’s dynamics and Coleridge takes full and subtle advantage of all those means. Here in these lines from the 1796 version of “The Eolian Harp,” for instance he creates a quietening effect rhythmically, by slowing the pace of the poem:

That italicized word so stands out, typographically more emphatic, but not, somehow, louder, than surrounding words. The word “so” (l.9) was italicized in the 1796 version of the poem (which appeared with the title “EFFUSION XXXV. COMPOSED AUGUST 20th, 1795, AT CLEVEDON, SOMERSETSHIRE”) and the word was also italicised in the version of the poem published in Poems (1803), entitled “Composed at Clevedon Somersetshire." We know that this emphasis was intended by Coleridge because he underlined the word (“so”) in the manuscript version of the poem he sent to Cottle for publication in 1796 (Rugby MS). However, the version of the poem published Sibylline Leaves in 1817 does not have the word “so” italicised.

The italicisation (or its omission) is significant in terms of how we hear the line, and also in how the line represents volume. The use of italics can create shifts of vocal tone but it can also contribute to shifts of pace and rhythm, which in turn suggests a dynamic effect, in this case, a quietening. Here, the italicization alters the rhythm of the line so that instead of the iambic pattern of “the WORLD so HUSHED,” that word “so” gains a stress, to the WORLD SO HUSHED. These three stresses in a row slow us down and the change of pace creates a feeling of intimacy—drawing us in, as it slows us down: together these contribute to the effect of diminuendo. There is a sense of quieting as we reach the word “hushed,” a slowing down which puts emphasis on the quiet it denotes, a quiet which fades to the silence of the white space at the end of the end-stopped line. The word “hushed” conveys the sense, still current, of “Reduced to silence; silenced, stilled, quieted” (OED): in slowing the pace of the line by emphasizing the word “so,” Coleridge creates a stilling effect rhythmically, and this contributes to the quietening of volume described and enacted.

The rhythmic shift in the next line, sounded in the phrase “the stilly murmur,” with its return to an iambic pattern, contributes to a steadying which suggests a quietening effect. The rhythm of the line shifts in the phrase “of the distant sea,” so that the word “distant” is emphasized after two unstressed syllables (“of the”); this shift in perspective is also suggested semantically as we shift from the proximity suggested by “murmur,” suggesting the “low continuous sound of water” (OED, 2) but also a quiet speaking voice, “A word or sentence spoken softly or indistinctly; faint or barely audible speech” (OED, 4).

This “murmur” is a quiet voice we can hear only if we are close to the sound; a shift from this suggestion of proximity to “distant” produces a fading effect, a kind of diminuendo. Once again, a shift in pace and rhythm contributes to a quietening effect. There is a slowing of pace, suggested by the thickening acoustic texture of the lines with their alliterative clustering of s sounds that concentrate in, and emphasise, the final word of the sentence, “silence”: “the stilly murmur of the distant sea/ Tells us of silence.” This is an example of the kind of interplay between sound and semantic meaning which T.S. Eliot understood was key to the auditory imagination, that “feeling for syllable and rhythm, penetrating far below the conscious levels of thought and feeling, invigorating every word” (T.S. Eliot, ‘Matthew Arnold’, in T. S. Eliot, The Use of Poetry and the Use of Criticism (London 1933) p. 119). Coleridge creates acoustic shifts in and through rhythmic and verbal textures and contextures in many different ways, including the use of emphatic markings such as underlining or italicisation as well as through shifts of rhythm and pace, as he does in these lines.

The change in register in the line “the stilly murmur of the distant sea” also contributes to a sense of historical distance, and to a related sense of acoustic distancing or quietening, diminuendo. The line, “the stilly murmur of the distant sea,” sounds archaic with its balanced pairs of adjective and noun- stilly murmur, distant sea- in which the st sounds chime with stilly and distant. The word stilly, in itself archaic, denotes not moving, and so the slowing down effect of the previous line, the world so hushed, leads to this articulation of stilly-ness. A still sea, is, of course, a silent sea, and, as we might expect, another sense of the adverb “stilly”, recorded in OED, bears this out; “In a still manner; silently, quietly; in a low voice; †secretly.” The sea is very quiet and therefore tells us of silence. It is an odd thing to say, that it tells us of silence. That of is intriguing. It’s not that the sea is silent, it tells us of – about - silence, a story of silence, perhaps. This is a playfully indirect, and perhaps we could say a quieter way of telling us that the sea is silent, a syntactic distance opens up into a deeper silence.

In “The Nightingale: A Conversation Poem,” the play with sound and semiotics takes another form: the invitation to listen at the heart of the poem is not voiced, but silent, signed rather than said:

My dear babe,Who, capable of no articulate sound,Mars all things with his imitative lispHow he would place his hand beside his ear,

His little hand, the small forefinger up,

And bid us listen! (ll.91-6)

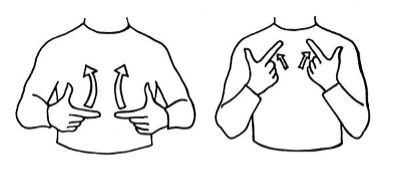

Here in these lines Coleridge is offering us the sign language of a pre-verbal baby, and inviting us to think about the silence of signs on the page. It is interesting to note that it was in the Romantic period that a new codified form of sign language for the deaf was developed in France (Jacobus: 2012, 84-88). Coleridge’s baby’s gesture can be better understood when placed in relation to some recent examples of sign language in the work of deaf poets Raymond Antrobus and Ilya Kaminsky as part of their own enquiries into the forms, dynamics and politics of signs and silence.

Antrobus’ poem “Two Guns in the Sky for Daniel Harris”, for example, commemorates the deaf man Daniel Harris killed after police officers, who had been chasing him for speeding, misinterpreted his use of sign language and shot him. The poem interrogates the difficulties of interpreting sign language; Antrobus was trained in British Sign language, which is different from American Sign. But a failure to understand sign can, as Antrobus points out in the poem, have tragic consequences. He examines the cruel irony that the ASL sign for alive looks like two guns pointing up to the sky:

Figure 2. Figure 2. ASL illustration by Oliver Barrett, which readers are left with as a closing image in Antrobus' poem "Two Guns in the Sky for Daniel Harris," (Penned in the Margins, 2018).

Coleridge’s hand sign is not ambiguous and its clarity is part of its own expressive poignancy.

In “Frost at Midnight,” composed and published in the same year as “The Nightingale: A Conversation”, this interest in signs and sounds and their correspondences is richly played out, from the very opening lines:

The Frost performs its secret ministry,Unhelped by any wind. The owlet’s cryCame loud—and hark, again! loud as before.The inmates of my cottage, all at rest,Have left me to that solitude, which suitsAbstruser musings: save that at my sideMy cradled infant slumbers peacefully.'Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbsAnd vexes meditation with its strangeAnd extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood,This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood,With all the numberless goings on of life,Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flameLies on my low burnt fire, and quivers not;Only that film, which fluttered on the grate,Still flutters there, the sole unquiet thing.Methinks, its motion in this hush of natureGives it dim sympathies with me who live,Making it a companionable form,Whose puny flaps and freaks the idling SpiritBy its own moods interprets, every whereEcho or mirror seeking of itself,And makes a toy of Thought. (CW, Poetical Works I, ll. 1-23)

The poem’s very first lines signal an interest in the relation between eye and ear in a visual rhyme, or ‘eye rhyme’ between “ministry” and “cry.” This silent eye rhyme is part of the poem’s play with the way sound is codified or represented in visual form, in the semiotics of sound in print. The sound of that “cry” is picked up later in the half-rhyme with “side” and later “life.” Perhaps it’s too much of a stretch to suggest that t the long I sound, or “eye” rhyme, is registered to the eye but not to the ear in “live.” Nonetheless, in these lines Coleridge invites us, in different ways, to move in and out between eye and ear, between rhyme seen and rhyme heard. Throughout the poem eye and ear work together and askance in unexpected ways.

Another striking feature of these opening lines is the dramatic dynamic shift from the “loud” cry of the owlet outdoors to the quiet of the indoor scene, a shift which produces a sense of intimacy and interiority and the accompanying illusion of diminuendo. That word “loud” primes our listening ears for a certain pitch of sound, which emphasizes in contrast the subsequent lines’ account of quiet. The poem’s shifting dynamics depend on and produce shifts in intimacy as it records a shift from outside to inside, from loud noise to quiet. The word “secret” in the very first line suggests both quiet and intimacy, since “secret” carries the suggestion, now obsolete, but current when Coleridge was writing, of reticence, or quiet: “Of a person: †Reserved or reticent in conduct or conversation (obsolete); not given to indiscreet talking or the revelation of secrets; silent as to any matter, uncommunicative, close.” (OED, 2 a). By giving the frost a curious sense of human agency, it “performs a secret ministry,” Coleridge draws out association of “secret” with quiet and closeness

The poem creates this sense of closeness dramatically, too, so that the reader feels as though we are standing with the poet, listening with him. This is expressed in the shift from the past tense “came loud” to the present tense “hark again!,” from the temporal distance of the past tense to the sense of immediacy suggested by HARK which instructs the reader, now, give ear, listen! The reader imaginatively is listening but also aware of being a reader, something of which the poem deliberately reminds us.

Since M.H. Abrams’s classic and influential account of the poem as one of the Great Romantic Lyrics, it has been understood in terms of vocal utterance, as a Conversation poem (Abrams, 1965). Coleridge’s “Conversation Poems” play with the dynamics of sound and its representation in curious ways. Much has been made of the vocal quality of these poems; critics have focussed on their various forms of address and the cadences of familiar conversation

. And yet the poem itself places much emphasis on non-human sounds, sounds that are increasingly abstract and hard to imagine. The owl, the crackling fire, the fluttering speck, the dream (inaudible to another), the quiet shining of the quiet moon. Indeed, the model Coleridge chose to describe the poem was musical rather than vocal or dramatic: he conceived of the poem in musical terms, as a Rondo, a form which was extremely popular in the late eighteenth century. In an earlier draft, the poem ended with six lines which describe the baby’s response to the icicles. Explaining why he cut these lines, Coleridge wrote: ‘The last six lines I omit because they destroy the rondo, and return upon itself of the Poem. Poems of this kind & length ought to lie coiled with its ‘tail round its’ head.” (CC, 16.1.1, p.456n.). Coleridge had taken Charles Burney’s General History of Music out of Bristol library a few months before he composed “Frost at Midnight” (in November 1797), and may well have read the account of the rondo in its pages (155). His interest in Burney’s book around the time he wrote “Frost at Midnight” suggests a rich and suggestive musical context for interpreting the poem’s sounds and silences.

Understood as a musical form rather than overheard speech, the poem invites a different kind of listening.

One which creates effects of volume and marks its shifts between loud and soft in playful ways. New possibilities for interpretation open up if we think of it not in terms of its orality, as a Conversation poem, to use Abram’s term, but in terms of aurality, as a listening poem. A poem which meditates on the experience of listening not just to the sound of a voice, but to the sounds of the non-human, the owls, the fire, the quiet itself. And it creates the effects of quiet through particular codes and patterns of sound and meaning.

If we put pressure on the poem’s acoustic language, its imaginings and figurings of sound, and think not only of the vocal cadences but also other forms and shapes of sound, abstracted from a notion of voice, pattern takes on a new significance. According to Marjorie Levinson, attending to visual pattern is a neglected key to understanding the poem. In a recent study she “seeks to shift the sensory register of criticism of the poem from its traditional emphasis on the acoustic to a new appreciation of the visible” (“Parsing the Frost”, online version). She emphasizes the poem's visuality, rather than the acoustic qualities and expression. I would push this further and argue that Coleridge is deeply interested in the relation and the dynamics between the visual and the acoustic but also between the visual and the aural. Patterns can be heard as well as seen. Throughout the poem, Coleridge plays with the way visual and acoustic dimensions are intimately related. This is in part because the poem is written with a sense of its own mode of reception in mind: that is to say, Coleridge was keenly aware that it might be read in silence, and so was especially thoughtful about how sound might be represented in print patterns, on the page.

There is a curious play between eye and ear, for instance, in the poem’s concluding lines:

[…] whether the eave-drops fallHeard only in the trances of the blast,Or if the secret ministry of frostShall hang them up in silent icicles,Quietly shining to the quiet Moon. (ll. 70-74)

The beautiful and strange description of a moon shining quietly prompts a question, an imagining, of what a loud shining might sound like. On the one hand, the idea of a “quiet moon” is a folk idiom to describe a new moon, and indeed the poem was written at the time of the new moon. And yet the image is so much more suggestive. It is “quietly shining to the quiet moon”: that quiet repeated in quietly, emphatically. An icicle can be silent by imagined contrast: its silence remembers the sound of dripping water before it has frozen into an icicle, or after it thaws.

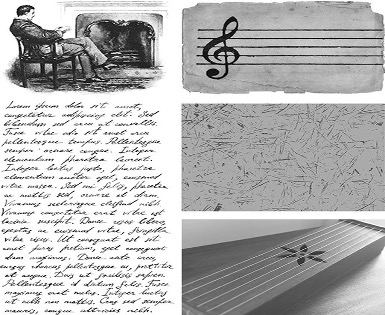

Another example of Coleridge’s interests in the play between eye and ear is the visual analogy to musical form described by Levinson: the fluttering soot on the grate, she argues, and suggests visually (in her fig. 7, reproduced below), can be read as a visual representation of a stave with a musical note. And to take this further, it is the semiotics of music, the semiotics of sound, that interest Coleridge here.

Figure 3. 18th-c Fire Grate, Journal Page, Musical Staff, Window Frost, Aeolian Harp. Fig. 7 in Levinson (2018).

vii. “the embryo science of acoustics”.

“Frost at Midnight” is a poem which explores the edges of silence. Coleridge has, as Susan Wolfson notes, an “ear for such limits, of sound suspended” (Wolfson, 2008: para. 3). There is an intriguing richness and, at times, an opacity to the poem’s acoustic language which rewards attention, and which, in turn, invites new readings and imaginings of the poem itself, and new possibilities for thinking about the quietudes of Romantic Lyric. The poem generates thinking about what it might it mean to shine “quietly”. And about how we might listen to the moon. And about the audibility and inaudibility of dreams. Setting the poem’s sonic and aural language in the context of Coleridge’s wider thinking about sound dynamics and acoustics and its imaginative possibilities, gives us some hints.

In 1827, Coleridge read Sir Charles Wheatstone’s “Experiments on Audition” and was struck by his account of the microphone, an instrument which, he explained, “rendered audible the weakest sounds” (70). Coleridge describes, in Marginalia, how it sparked a recognition of a “fond and earnest dream project of mine own …with sundry other imaginations in what might be effected in the only embryo Science of Acoustics” (197). The science of Acoustics, that “branch of physics concerned with the properties and phenomena of sound, sometimes esp. in relation to hearing or speech.” (OED,1), was just over 100 years old when Coleridge scribbled these words. As his marginal gloss suggests, Coleridge’s fascination with acoustics was apparent years before he read of Wheatstone’s invention: we find an interest in the properties and phenomena of sound registered in numerous notebook entries and poems.

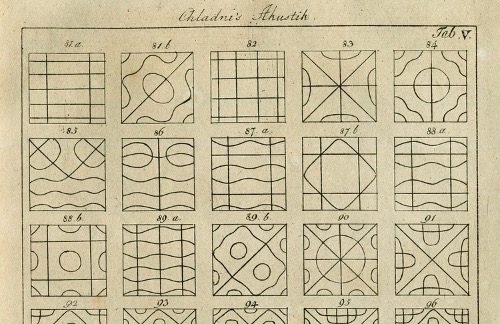

We know, for instance, that he was fascinated by the sound experiments of the musician and scientist Ernst Chladni (who was to publish the first textbook on acoustics in 1802), which seemed to show sound itself making shapes in iron filings.

Chladni drew a bow across the edge of a metal plate covered in sand before exclaiming, as legend has it: ‘The sound is painting!’ (quoted in Cox, 14). The significance of this experiment cannot be overstated: not only did it seem to reveal the material form of sound, but doing so Chladni proved that sound could travel through solid substances and could no longer “be subsumed under the ‘the science of air’ and could be considered a branch of physics in its own right” (Viktoria Tkaczyk, 27-56, 27). Chladni first published his acoustical figures in German in 1787, and gave a copy to the Royal Society in November of the same year. Coleridge may have read about the experiment in the Philosophical Magazine (3, May 1799, 389-96) in which a translation of the Jena physics professor Johann Heinrich Voigt’s 1796 account of it (“Beytrag in den Versuchen über die Klangfiguren schwingender Flächen”, Neues Journal der Physik vol. 3, part 4 (1796), 391-399) was published as “Observations and experiments in regard to the figures formed by sand &c on vibrating surfaces” (Philosophical Magazine, 3 (May 1799), 389-96, with illustrations). He may also have read of the experiment in The Analytic Review, volume 1 (July 1788, 371-2). Chladni toured Europe conducting performances of the experiment to enraptured audiences (including Napoleon, in the Tuilerries Palace); Coleridge may also have learned of the sound painting during his visit to Göttingen

, where he studied in 1799, a few years after Chladni had demonstrated the experiment (between December 1792 and early 1793, https://monoskop.org/Ernst Chladni ). The experiment was to be popularised in London in 1800 when Thomas Young repeated the demonstration to an enthralled audience at The Royal Society. The Chladni figures were part of a wider culture of acoustic spectacle in the early nineteenth century. Edward Gillen explains that in “London’s fashionable West End . . . sonorous displays, especially those of a musical nature, combined with philosophical inquiry, provided mystifying and wondrous entertainment” (1). He argues that “Chladni’s acoustic plates provided a rich example of how specialist and non-specialist audiences alike could engage with new scientific ideas from the Continent”. While I am not suggesting that Coleridge’s poems of the 1790s were influenced directly by Chladni’s experiments, I want to propose that they too register a curiosity about what he was to describe as “the Embryo science of acoustics”, which was itself part of a culture of curiosity about sound in the Romantic period.

Figure 4. Illustration of Chladni patterns in Ernst Chladni, Die Akustik (1802)

Coleridge’s own interest in the semiotics of sound and its representation is figured in the Conversation poems and based on his wider interest in science during his stay in Somerset the 1790s. As Tim Fulford has explained, the Conversation poems were influenced by and part of a wider culture of scientific enquiry. Pushing Fulford’s argument yet further, we might understand Coleridge’s Conversation poems as articulations of a growing interest in and curiosity not only about the nature of air, but also about a relate field of enquiry, the science of acoustics, and in particular, the movement and materiality of sound. In “Frost at Midnight” this interest was perhaps modulated by his sense of the poems’ expected mode of reception: he knew that it was likely to be read in silence, heard only in the mind’s ear. But it is also framed by its occasion, spoken to a sleeping baby who cannot hear him, at least not consciously.

The poem’s concluding lines meditate on the sounds and silences of water drops and icicles in a way that puts pressure on the language of listening:

[…] whether the eve-drops fallHeard only in the trances of the blast,Or if the secret ministry of frostShall hang them up in silent icicles,Quietly shining to the quiet Moon. (ll.70-74)

The word “silent” invites our listening. Here, in these lines, or perhaps I should say through these lines, our ears become subtly tuned to the sounds of silence which shifts gently into quiet. The line “quietly shining to the quiet moon,” picks up and resounds the i of silent icicles, recalling the sound of that silence even as it suggests a different sound. It’s worth noting here that the phrase is not, as it might have been, silently shining to thesilent moon – but quietly shining to the quiet moon, and this difference suggests a thawing of silence, since quiet can, but does not always or only, mean silent. Quiet can suggest a low or subdued sound (OED 1A, a, adj, “making little sound”; 2a, “making little or no noise”). That repeated word quietly dims into a shorter quiet, drawing the ear to listen in, to the possibility of the moon’s quiet sound. And the line has only 4 stresses instead of the 5 stress iambic baseline of the poem, so we are left both with a sense of lack- and anticipation - listening out for the last stress.

There’s a sense of diminishing and diminuendo, but also a feeling of completion as “quietly” turns to “quiet,” and as we move from “icicles” to the monosyllabic “moon”. This drawing in suggests both sonic diminuendo and intimacy, despite the great distance of the moon. The icicles are quiet because, unlike the water dropping from the eaves, they no longer splash and make a sound. There is a strange shift of scale and of distance here – one which prompts us to question how a moon might be quiet. That repeated word “quiet” suggests a kind of proximity and even, that it might be possible to hear the moon, that its sound might be quiet as the nearby icicles. The quiet shining of the icicles to the moon is imagined as a form of address, to the listening moon. These icicles are silent but eloquent: and yet their silence is not eloquent of the self in the way Salome Voegelin proposes. (83). Rather, it speaks of the presence of something greater. As Paul Magnuson puts it, “at the quietest moments of the year when the icicles are frozen in silence, there is a force in the world shining through the icicles.”

These silences speak of intimacy and also of something far more greatly interfused, a force in the world.

viii. Conclusion

For Coleridge, the ability to listen was fundamental to being a poet. A great poet, he suggests, writing in July 1802 to his friend William Sotheby, should be able to listen with “the ear of a wild Arab list’ning in the silent Desart” (Coleridge, Letters: ii, 810). We know that the Arab is listening, in silence – but we do not know what it is he listens to or for. The state of listening, of hearkening, for something is the poetic state. But silence also seems important: Coleridge’s test for the poet combines forms of privation – that emptiness, which shares the root ‘desert’: the dryness of deserts, the solitude of the deserted, and the soundlessness of silence. The wild Arab is alert for the slightest sound, listening FOR sound in silence. Coleridge’s words invite the reader too to listen: that word “listening” alerts us to the sound patterns instinct in the lines that follow. The poet, Coleridge goes on, should also be possessed of “the eye of a North American Indian tracing the footsteps of an Enemy upon the leaves that strew the forest, the Touch of a blind man feeling the face of a darling Child” (810). Primed to listen, the reader might pick up a suggestion of sound in the word footsteps (they are footsteps he is tracing, rather than the footprints we might have expected) and the sound of these footsteps resounds in the st sounds of strew and forest. And there is a gentle pathos in that word touch touching in sound the child as the blind man touches its face.

Thinking about different kinds of listening in a notebook entry a few months later, in September 1802, Coleridge returns to the blind man and the wild Arab as figures for sensory acuity. His choice of an Arab and a North American Indian as examples are striking and suggest, perhaps, a primitivist notion that such peoples had more acute senses than Europeans. Choosing these geographically remote listeners introduces a poignant distance between himself and the figure of the ideal listener, which in turn intensifies the dynamics of listening described. Here, the blind man and the Arab come together in the figure of “a blind Arab list’ning in the wilderness” (Coleridge, Notebooks, i. 1244): now the blindness of the listener intensifies his listening once again. And instead of the blind man feeling the face of the darling child we have, more painful, a different kind of listening, a listening which can never be satisfied, a “Mother listening for the sound of a still-born child” (ibid.) Silence here comes to represent an extreme form of loss and absence. Coleridge’s examples move through degrees of privation, from the blind Arab in the desart to the poignant expectancy of the mother listening for a sound that she will never hear.

To think about the representation and account of sound in these poems in relation to contemporary scientific instruments and innovations in acoustics, and also, as I have indicated, to a wider culture of curiosity about how sound could be represented and embodied on the page in music and in print opens up fresh thinking about the significance of silence and quiet in Coleridge’s poems, and in Romantic lyric more widely. What is needed is a new kind of listening, which includes attention to the dynamics of apostrophe, the cryptographic reading described by John Shoptaw, that, “listening for what familiar words and phrases the line echoes or calls to mind,” as well as the phonemic analysis described by James Lynch,

a composite kind of imaginative auditory attention, one which is attuned not only to the ghosts and echoes of words, and their phonetic clustering, but also to the shifting patterns and dynamics in and of sound, to the way a poem creates effects of volume. It is time that Lyric Studies expanded the range and frequencies of its listening.