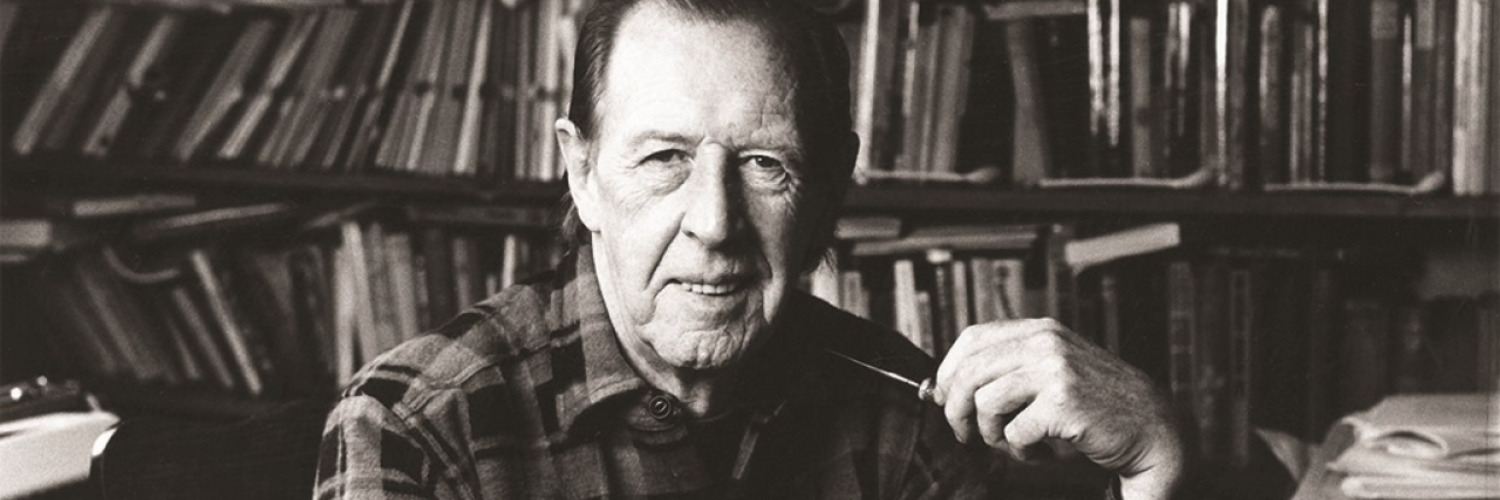

Why read Raymond Williams now? This is certainly not the first time this question has been asked. Shortly after Williams’s sudden death in 1988, Simon During wondered whether that event marked "the end of an era" or "the sign of a beginning set in motion by the program, the shifts of emphasis, he urged" (681). Ultimately, we might now say that his death was both an end and a beginning. Cultural Studies, whose contours, possibilities, and limitations were so much a part of the early debate that followed Williams’s death, has now become an established, if not dominant, component of literary studies. The wide range of its approaches has meant that Williams’s assumptions about culture have pollinated various forms of analysis rooted in understandings of culture’s centrality to nation, empire, ecosystem, and to identities formed around race, class, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability, and disability. Most of these approaches, except for class, were met with relative silence in his own corpus. But literary and cultural work today remains indebted to the quality Williams attributed to Brecht and which applies to his own work as well: an unparalleled capacity for "the ‘complex seeing’ of a multivalent and both dynamic and uncertain social process" (Politics of Modernism 91).

This collection addresses Williams’s long and complex relationship to Romantic works and to the Romantic period itself. Few works have generated as much critical thinking about Romantic writing’s literary purposes and social meanings as Culture and Society: 1780–1950 (1958), The Long Revolution (1961), or The Country and the City (1973), but many of Williams’s other works have spoken to Romanticism’s moment in different keys that our essays explore as well. Such reflection comes at a time today when Williams’s methods and legacy have come under new critical pressure. From one angle, critics like Joseph North have used Williams to stand for the domination over "criticism" by the "historical-contextualist" method he is credited (or blamed) for building. From a different angle, Williams’s legacy is now said to belong to the party of "critique" whose dark materialism appears to negate literature’s pleasures and other affects of many kinds.

These new vectors of disciplinary debate, reasserting divides between the personal and historical, the critical and scholarly, are tacitly but unmistakably at issue in the perspectives on Williams’s work we present here.

The work of Raymond Williams has by no means become dated by, or limited to, the moments of its emergence in the 1950s and 60s. In recent years a range of scholars have been moving the legacy of Williams in new directions, some surprising or unforeseen. Lauren Berlant, for one, uses Williams’s concept of "structure of feeling" to construct her materialist version of affect theory, tracking what she calls "the becoming historical of the affective event and the improvisation of genre amid pervasive uncertainty" (6). Within this process, "affective responses" come "to exemplify shared historical time" (Berlant 15). Lisa Lowe also uses Williams’s structure of feeling and his related framing of dominant, residual, and emergent forms of culture to produce a materialist understanding of intimacy, one that pluralizes intimacy to produce what she calls a "political economy" of intimacies (Lowe 18). But affect theory is not the only way that Williams continues to inflect contemporary work. At the opposite end of the spectrum, we might also read his sociology of culture as shaping the ambitions of approaches like "cultural analytics" and other computational models that aim to show how new digital techniques like network analysis can expand the scale and scope of the way we study cultural forms (Dunst).

By almost universal agreement, Williams’s writings represent an argument for the centrality of "culture" in literary, social, and political analysis, and it is around the turn of the nineteenth century, as his accounts repeatedly insist, that the Enlightenment idea of culture thickens, as it were, and through variations and complications begins to build into itself the contradictions of its development. We see this argument emerge initially in Culture and Society (1958) and develop through The Long Revolution (1961) and beyond as Williams distinguishes between two interrelated ideas of culture: first, as the development of an achieved social order akin to civilization as presented in eighteenth-century universal histories and later challenged by Rousseau and Marx, among others; and second, a related but distinct concept of culture found in the common rituals of everyday life and what Williams repeatedly calls "a whole way of life."

I

Several of our essays assert, while others imply, an important shift in Williams’s career between earlier work like Culture and Society, where he is grappling with the English moral and formalist criticism in which he had been trained, and a later stage typified by works like Marxism and Literature (1977), where he brings to fruition the new theory and methods of cultural materialism. In our lead-off essay, "Williams and the Romantic Turn," James Chandler argues that Williams’s engagement with Romanticism as a category belongs more clearly to the first phase of his career than the second, as both Culture and Society and The Long Revolution query and challenge the Romantic figure of the creative poet galvanizing "imagination" to distance us from everyday life, promising access to a "superior reality" instead (Long Revolution 32). Chandler turns his argument on a rich, surprising reading one of Williams’s least-cited books, Modern Tragedy (1966), where the dialectical movement of categories like Romanticism, liberalism, and drama form an unexpectedly decisive turning point for Romanticism’s place in modern cultural history. In what Chandler calls the sociological turn in Williams’ thinking after 1966, the moment of 1800 would remain an important pivot in the cultural history of modernity, but it was now understood as caught up in many movements and modes of writing beyond the traditional Romantic canon itself. What should be done, this volume asks in turn, with Williams’s several legacies?

The essays collected here respond to this challenge in a variety of ways, though all reflect on how we should read Romanticism in light of Williams’s early and late work. Some, like those of Kevin Gilmartin, Mary Favret, and Brian McGrath, seek to open up a reconsideration of Williams through attention to his particular treatment of Romantic authors like Jane Austen, William Cobbett, and William Wordsworth. Others, like those by Thora Brylowe and Paul Keen, use Williams’s legacy to take stock of current conversations on the situation of university study and the place of the humanities within it. Meanwhile, Jon Mee’s essay puts into question Williams’s way of counterposing "culture" to "industrialism" as a basis for thinking in broader terms about the meanings and inflections of materialism, both in its historical manifestation in Romantic era intellectual life and in critical methods arising from Williams’s work. Some essays make renewed use of Williams’s best-known work, like The Country and the City or Marxism and Literature, while others turn fresh and vigorous attention to his less cited contributions, such as Modern Tragedy, Television, or Williams’s slim Past Masters volume, Cobbett. Literary questions—of narrative, grammar, style, medium, form—claim central attention in these essays. What unites them too is an awareness of the complexity and vitality of Williams’s approach to culture and an admiration for his sustained attempts to develop a method for studying culture appropriate to its capacity for mobility and change. Building from this work, our introduction provides a context for the essays to follow while also offering an argument of its own by raising further questions on the methodological side of Williams’s oeuvre.

Williams argued for a concept of "structure of feeling" as early as his 1954 Preface to Film (cowritten with Michael Orrom), and the term appears casually in Culture and Society before being developed more seriously as a concept from The Long Revolution onward. The inflections and implications of the term changed over time, but Williams consistently used it to capture the dynamic between the personal and the historical, the means by which a complex set of relationships reveal unexpected correspondences and discontinuities, thus precipitating, as it were, distinct elements of contact out of the history "in solution" of a complex whole.

He argued that it is in the arts of a period that these elements are grasped most distinctively. As David Simpson put it in a 1995 essay, "Williams seems to want to offer art and literature as the most complex barometer of movement at the ideological level, and to propose the structure of feeling as a kind of super-sensitive indicator of such movement" (17). Within Romantic studies, the work of Kevis Goodman and Mary Favret has done as much as anyone’s to read this barometer. They use it to locate, as Goodman puts it in her book on the georgic, "that immanent, collective perception of any moment as a seething mix of unsettled elements," while reminding us that by "feeling" Williams meant especially the "unpleasurable sensations of ‘disturbance, blockage, tension’" (Goodman 3, 70). Their work and that of others show that culture and the historical present is always on the move, part of a process that must necessarily be grasped historically, though it is also pervasive below the threshold of articulation.

But there was also a complex evolution in the concept of "structure of feeling" over the course of Williams’s career. From its earliest formulations in the 1950s and early 60s, Williams found the structure of feeling visible in texts, "at the edge of semantic availability" in drama, films, or novels. Whether it was Chekhov’s particular structure of feeling in Drama from Ibsen to Brecht or Elizabeth Gaskell’s version in the industrial novels Williams studied in The Long Revolution, he located a structure of feeling in the works of individual writers and the literary conventions they either changed or introduced. Meanwhile the social sources of this feeling were inchoate, arising out of what he called "deep community," "the culture of a period," or, in his widest formulation, the "living result of all the elements in the [social] organization" (Long Revolution64–65). What was not specified was how exactly the minute particulars of a structure of feeling were connecting to the widest social realm.

Those ways of thinking about the structure of feeling were significantly altered when Williams’s work took a more explicitly sociological turn with Marxism and Literature (1977) or in his last completed work, The Sociology of Culture (1981). Marxism and Literature devoted several intensive pages to the structure of feeling, and here for the first time the idea is pluralized as "structures of feeling" (128–35, our emphasis). The plural changes the meaning and scope of the concept in several key directions. There is a telling shift from single writers to groups of writers or cultural producers—to what Williams began calling in another chapter "cultural formations" (138). While there is the same emphasis on "social experiences in solution," the terms of analysis are now far more precise. There is a new concreteness to specifying such structures in history beyond the individual writer or text, as Williams now speaks of "the complex relation of differentiated structures of feeling to differentiated classes" and other senses in which structures of feeling gain their affective force from highly particularized historical encounters (Marxism and Literature 134).

Williams’s characteristic and unparalleled ability to thicken the historical experience of his subjects comes through clearly in Kevin Gilmartin’s essay, “‘In His Time and in Ours’: Reading Cobbett (and Jane Austen) with Raymond Williams.” For Gilmartin, Williams offers a properly literary reading of Cobbett’s work, one attuned to Cobbett’s style in a manner that shows how historical method itself can be understood as a matter of style. More particularly, Cobbett allows Williams to reflect on historical process and "unanticipated historical experience." Such contingency then becomes, through Williams’s comparison of Cobbett with Jane Austen in the “Three around Farnham” chapter of The Country and the City, an encouragement to think historically about class. In Gilmartin’s account, we can see Williams’s earlier emphasis on shared historical experience transform into a more sophisticated understanding of the particularities of class, the institutional structures of culture, and the historical contingencies that make the relationship between class and culture so particular and complex.

Mary Favret’s essay, “Raymond Williams on Jane Austen, Again,” also takes up Williams’s account of Austen from the “Three around Farnham” chapter in an effort to grasp the motion and movement of historical experience. She suggests that Williams repeatedly presents Austen as a "static" writer, a subject whose contours can be taken as a given, but that the fixity of Williams’s account of Austen then sets his analysis of Cobbett and others into motion. Making her case at the level of the word, the sentence, the paragraph, and attending even to the look of the page in Williams’s published work, Favret registers the acute peculiarities of closeness and distance, of scale generally, through her toggling between the semantic units of Williams’s writing, especially as they bear on qualities of vision and seeing. For Favret, even the page itself in Williams’s work functions as an image that needs to be navigated and mapped by the eye. This visual emphasis sets up a pivot in Favret’s essay from Williams’s literary analysis in The Country and the City to his theorization of media in works like Television: Technology and Cultural Form. What happens to Austen, Favret asks, when we look at her work through the terms Williams develops for new media and focus on motion, temporality, and tempo rather than the visual and spatial terms that Williams uses to "fix" Austen in behind her wall? Favret’s reading of Austen’s adaptation for screen stands also as a salutary reminder of how reading Williams, even against the grain, can produce new perspectives on seemingly familiar Romantic texts.

II

In its subtle shifts of meaning as Williams develops the idea of a "structure of feeling" across his earlier work to his subsequent reflection on the term’s usefulness in the New Left Review interviews of 1979, we can see how the expression evolved from understanding culture as something rooted in "experience" to a conception of culture as produced by "practices." "It took me a long time," he told his New Left Review interviewers, "to find the key move to the notion of cultural production as itself material" (Politics and Letters 139). First fleshed out in his essay “Base and Superstructure in Marxist Cultural Theory” (1973), the concept of cultural production permitted an enormous range of materials to enter the purview of cultural analysis, from writing to visual and electronic media, offering a more theoretical basis for what cultural studies, then still a British set of critical practices, was already doing on the ground. Though this notion sometimes obscured the place of economic determinations in classical Marxist terms, Williams defended "cultural production" as a concept that did not make production less important than culture, but more important and pervasive than the base/superstructure model could ever allow (Politics and Letters 145). And what he had earlier sometimes attributed to a preanalytical category of naïve experience was now to be found in what he called "the common character of the respective processes of production" (139).

As Brian McGrath notes in his essay, “Determination in the Passive Voice (Wordsworth and Williams),” the chapter “Determination” comes just after the “Base and Superstructure” chapter in Marxism and Literature and before Williams’s creative rethinking of "Productive Forces." McGrath turns from these texts to tarry with Williams’s Keywords (1976) as his point of departure for teasing out the meanings of determine in Romantic poetry and Marxism alike, putting equal pressure on Romanticism’s freedom-seeking lyrical "I" and Marx’s senses of determination by wider forces. Citing Williams’s provocative phrase "I am determined not to be determined," McGrath follows the paradox into Wordsworth’s Prelude and tracks the grammatical pattern the Romantic poet shared with Williams himself, a strategic recourse to the passive voice. Here, we might say, the structure of feeling is "determined" insofar as it is simultaneously shaping and being shaped, with the inflection of both activity and passivity that McGrath draws out in Wordsworth and Williams.

Many of the implications of "cultural production" are not fleshed out in Marxism and Literature, a work of theory, but rather in his counterpart manual on methods in The Sociology of Culture, where Williams asks more pointed questions about the material "means of cultural production" and about who produces culture and how. One salient idea impressed on him by Lucien Goldmann’s work was that cultural production takes place most importantly not at the level of individual writer and his relation to some "abstract group," as in mainstream sociology, but rather between "individuals in real and collective social relations" ( “Literature and Sociology” 23). For Williams this came to mean thinking about production as carried out by highly particularized groups. His expression for these groups—"cultural formations"—has hardly ever been cited in this specific sense, in part because each term has so many wider uses that the phrase does not indicate how specific and useful it actually is. Such formations were not unknown to earlier kinds of literary history: they include "conscious movements and tendencies (literary, artistic, philosophical or scientific) which can usually be readily discerned after their formative productions" (Marxism and Literature 119). But the new conception pushes Williams further away from grand synthetic categories like "Romanticism" and closer to particular clusters whose members combined shared aesthetic and social aims. He gestures briefly in The Sociology of Culture to a Godwin circle in the 1790s, a later Shelley formation, the pre-Raphaelites, and the Bloomsbury group of the 1920s, but the idea clearly has a far wider potential range than these familiar kinds of circles or coteries.

Williams’s theoretically elaborated reworking of such groupings under the heading of "cultural formation" both investigates the internal complexities of such groups and maps them onto wider social dynamics.

A reconceived idea of such cultural formations appears in Jon Mee’s essay, “Raymond Williams, Industrialism, and Romanticism, 1780–1850.” Arguing that Williams’s idea of industrialization remained abstract and unexamined, Mee shows how his later methods of cultural materialism can be used to locate a far greater complexity in the relations between literary production and industrialism. Rather than a centralized group working in cities like London, Mee studies the northern English writers who formed durable networks through the new literary and philosophical societies from Newcastle and York to Manchester and Liverpool, forging what Mee calls the "transpennine enlightenment" that led from the Rational Dissenters of the 1780s to Elizabeth Gaskell and Robert Owen in the 1840s. The methodological gambit of his essay is to link Williams’s materialist methods of immanent critique to Latour’s tools of network analysis, following the "pattern of recurring links" that such writers forged in a particular structure of feeling underlying this English "culture of improvement." Beyond urban circles, Mee’s revisionary transpennine cultural formation reveals new dimensions possible to follow from Williams’s own conception.

Locating and studying such cultural formations became Williams’s method for confronting what his late work called the "central problem" of literary and cultural analysis—how to understand "the specific relationships through which works are made and move" ("Uses" 28). In the 1986 essay “The Uses of Cultural Theory,” he located theoretical ancestry for posing this question in the "sociological poetics" of Medvedev, Bakhtin, and others who challenged the Russian Formalists in the 1920s. Against notions of an abstract intertextuality, Williams cites what he took to be a crucial passage from Medvedev: "Works can only enter into real contact as inseparable elements of social intercourse . . . It is not works that come into contact, but people, who, however, come into contact through the medium of works" (qtd. in “Uses” 29).

This relation of works and actors was for Williams the matrix of the cultural formation. In these later writings, the terms collaborative and collaboration received increasingly strong emphasis as he also pushed harder against the figures of Romantic author, the solitary cultural producer, and the enthronement of the modern critic. Impressed at how cogently Goldmann’s work was encouraging him to think about cultural production as "an active and collaborative critical process," he recalled that his most critically embattled book, The Long Revolution, had been written with "a crucial absence of collaboration" ( “Literature and Sociology” 24).

Our final two essays draw on Williams’s later work to reflect on collaborative processes as they bear on the state of the contemporary academy. For Paul Keen in “New Maps: Raymond Williams’s Radical Humanism,” Williams’s method maps culture in part by consistently resisting the allure of theoretical abstraction in its revision of Marxist theory as Williams emphasizes the concreteness and sense of complexity needed to grasp the contradictory character of Romantic era writing. Keen stresses some of the difficulties in coming to grips with Williams’s skeptical way of "unlearning" past versions of formalism or Marxism, as for instance the extensive previous reading in theory required to grasp the interlaced arguments in Marxism and Literature. Keen assesses the pertinence of relevant work by Edward Said, Timothy Brennan, and Georg Lukacs for thinking about Williams’s characteristic way of configuring cultural critique. Granted these challenges in reading Williams now, Keen also stresses the value of the "unflinchingly dialectical nature of Williams’s work" for the public role of the humanities today and the critical tools needed for confronting the digital revolution, the crisis of the humanities, and related forms of contemporary complexity.

In her chapter, “Book History and the Politics of Work and World,” Thora Brylowe too hopes to show the relevance of Williams for newer methodologies and questions. Emphasizing the central concept of labor for making sense of literature itself and the academic contexts in which it is studied, Brylowe underscores how Williams can help us to elicit the political urgency in newer methodologies like her preferred concept of "media ecology." Her essay stresses the collaborative, labor-based processes responsible for producing books and other artifacts of culture, the "hands and minds who never wrote a word," to demonstrate how abstractions like literature are produced in bookstores, libraries, papermills, coal mines, and (today) server farms. Brylowe, in other words, uses Williams to ask about the particular people who make the media through which words and works are transmitted, as well as to show the specific material processes that produce and circulate artifacts that contain information, imaginative content, and/or ideas.

Cultural formations entailed rich and thoughtful modes of collaboration, but Williams’s idea of how their cooperative work clarified the problem of structures of feeling remained a work in progress by the time of his death. We want to conclude by citing a telling passage from the last chapters of Marxism and Literature: ‘Something new happens in the very process of conscious co-operation. . . . But it is from just this realization that the second and more difficult sense of a collective subject is developed. This goes beyond conscious co-operation—collaboration—to effective social relations in which, even while individual projects are being pursued, what is being drawn on is trans-individual, not only in the sense of shared (initial) forms and experiences, but in the specifically creative sense of new responses and formation. This is obviously more difficult to find evidence for, but the practical question is whether the alternative hypothesis of categorically separate or isolated authors is compatible with the quite evident creation, in particular places and at particular times, of specific new forms and structures of feeling. (Marxism and Literature 195)’ Passages like this, along with his later work in The Politics of Modernism, show Williams still experimenting with new ways to think through the connections between feeling, perception, and social being, and how they might be located between cultural producers at work on shared projects and a wider, emergent social awareness that is still unformed. It is worth recalling, of course, that his idea of cooperation was informed by a long socialist tradition of regarding cooperation in the labor process as vital to any creative overcoming of exploited labor, a meaning sometimes lost in more facile thinking about collaborative work today. We might also take Williams’ term "trans-individual" in another sense not available to Williams in his time, since the word evokes a notion of interpersonal networks in ways that earlier terms like collective consciousness may not. All these questions arise in Williams’s work at a time when Romantic-period scholars are searching for conceptions of cooperative authorship, constructive social networks, and other forms and interconnective means of producing cultural projects, whether literary ones at the turn of the nineteenth century, or scholarly ones in the early twenty-first. The essays in this collection speak with imagination and power as well as with different minds about such matters; we think they will be immensely suggestive about ways to think with the work of Raymond Williams once again now.