A few years ago the institution that employs me put together an advertising campaign that I enjoy imagining as Hegel-inspired. For purposes of attracting donations and student applications, the campaign’s featured slogan, "Determined Spirit," describes a shared, tenacious drive. And indeed, Clemson students often win awards for what gets called "school spirit." But given the various and sometimes competing senses of "determined," the slogan also introduces the possibility that "spirit" at Clemson is expected, even compulsory. A determined spirit, in other words, is also a predetermined spirit, a spirit determined in advance.

In his Keywords, Raymond Williams explores the complex range of definitions associated with the word determine as he focuses on the distinction between determination and determinism, where the word determination refers to an unwavering individual will and the word determinism refers to the opposite, a will caught up in general processes beyond its control. Williams writes that even the most insistent and pseudoauthoritative application of one fixed sense of the word determined cannot avoid the other line of meaning. He illustrates the potential difficulty determine introduces with the sentence, "I am determined not to be determined," where the two meanings of determine vie for control (Keywords 102). On the one hand, the "I" of the sentence is resolved to remain free from determination, free from all constraints, bounds, and definitions. In this way the "I" pursues a model sovereignty. On the other hand, the sentence also suggests that this pursuit of a model sovereignty is already and from the start determined, a sign of the subject’s unfreedom; there may be nothing less free than the subject’s supposedly free pursuit of freedom. And even these two broad interpretations of Williams’s sentence do not exhaust the interpretive possibilities, which is one of the reasons he offers it. One might still stress how the sentence produces an "I" that is resolved to be unresolved, an "I" that would prefer not to act and will say "no" to making any and all future decisions: "I am determined not to have to determine anything (myself)." Or perhaps this "I" has been determined this way, an "I" destined for indetermination: as if Williams had in mind Melville’s Bartleby or were commenting on the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Roberts. Needless to say, the sentence is not easy to translate, though as an experiment I did type the sentence into Google Translate and received this sentence in German, "Ich bin entschlossen, nicht bestimmt zu sein," which takes care of some of the difficulty determined introduces into English by translating one use of determined as entschlossen and the other as bestimmt. If one feeds this German translation back into Google Translate one receives in return: "I am determined not to be specific." Not uninteresting, but not quite the same.

For Williams, the problem of determination takes particular shape during the nineteenth century, as it becomes increasingly difficult to disentangle the concept of determination from Marxism on the one hand (as Marxism focuses attention on the ways preexisting conditions fix a course of events) and Romanticism on the other (as determined comes also to mean "unwavering" or "persistent," and as the idea of the sovereign individual, the lyric "I," takes shape). William Keach develops this line of thinking in Arbitrary Power, where he remarks on the importance of determination to the nineteenth century: "Whether as a question of the ‘general will’ of the polis or of the individual will of a political agent or writer, ‘determination’ structures nineteenth-century efforts to understand the constitution of society and culture" (22).

My interests are in part historical. With Williams’s attention in mind to the importance of determination as a concept during the nineteenth century and his attention to the ways its meaning shifts, I turn to Book I of William Wordsworth’s The Prelude, which features the word determined at several key moments. As Wordsworth begins his biographical poem, he wonders whether he was determined by some external force to be a poet and whether he is determined enough to become one. In this essay I track these two competing definitions of determined through the writing of Williams and Wordsworth, a Marxist cultural critic on the one hand and a Romantic poet on the other. As critical concepts open to caricature, Romanticism and Marxism are sometimes placed in tension: where Romanticism prioritizes the power of the individual will, Marxism prioritizes the external forces that condition it. But the texts we choose to read closely often challenge the characterizations we bring to bear on them. Williams, for instance, struggles against Marxism’s focus on economic determinism, and Wordsworth concludes Book I of The Prelude—a poem that celebrates certain forms of self-determination—by foregrounding the importance of "determined bounds," bounds that have been determined by others. In this way, both writers are sensitive to the various and sometimes competing senses of "determination" in their work.

But in placing Wordsworth alongside Williams my interests turn grammatical, for Williams and Wordsworth are often drawn to the passive voice in their writing about determination. They also both frequently employ empty grammatical subjects when writing about determination, which has the effect of making the subject of a key sentence about determination itself difficult to determine. Some of the interpretive problems posed by Williams’s sentence ("I am determined not to be determined") might be described in grammatical terms: is the first-person pronoun the agent of the action (in which case the sentence is read as active voice) or is some other, unnamed subject the agent of the action (in which case the sentence is read as passive voice)? The difference emerges when one rewrites the sentence, for instance, as "I am determined (by my class) not to be determined." If both writers share an interest in determination and its various and competing connotations, what can we learn about the concept from attending to the grammatical, even stylistic, choices writers make when writing about determination?

No Problem More Difficult

In Marxism and Literature, Williams begins his chapter “Determination” by identifying the term’s importance to Marxism: "No problem in Marxist cultural theory is more difficult, than that of ‘determination’" (83). Williams attempts to rescue Marxism from too rigid an emphasis on determination without, however, giving up on the importance of the term to cultural theory in general. As he concludes the first paragraph: "A Marxism without some concept of determination is in effect worthless. A Marxism with many of the concepts of determination it now has is quite radically disabled" (Marxism 83). Today, given developments in disability studies, the subtle personification of Marxism as "radically disabled" is difficult to ignore and worth attending to. But Williams is attempting to navigate between, for him, two undesirable versions of Marxism, neither capable of developing an adequate cultural theory: one without any concept of determination and one with too rigid a concept of determination.

Williams attempts to rescue Marx from Marxism, as he objects to the ways determinism became widely known, in Marxism, as "economism" (which Williams describes as "worthless" [Marxism 86]). Certain versions of Marxism, and certain poor readers of Marx, totalize determinism as economism and mistakenly erase from Marx any idea of direct agency. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Williams laments, Marx gives way to Marxism: "With bitter irony, a critical and revolutionary doctrine was changed, not only in practice but at this level of principle, into the very forms of passivity and reification against which an alternative sense of ‘determinism’ had set out to operate" (Marxism 86). Williams argues against this abstract determinism, for the full concept of determination is crucial to save Marxism from such abstractions: "In practice determination is never only the setting of limits; it is also the exertion of pressures. As it happens this is also a sense of ‘determine’ in English: to determine or be determined to do something is an act of will and purpose" (Marxism 87). As in Keywords, Williams in Marxism and Literature turns to the resources of language itself, here the resources of the English language in particular, for help unsettling various attempts to fix meaning and thereby produce pseudoauthoritative doctrine.

To explore why "determination" is the most difficult problem in Marxist cultural theory, Williams turns to a well-known passage from the 1859 preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, which features what Williams refers to as Marx’s "normal word" for determine, bestimmen. "It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but, on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness," writes Marx in a paragraph that Williams quotes at length in “Base and Superstructure,” the chapter that immediately precedes the “Determination” chapter (qtd. in Marxism 75). As Williams notes when he returns to the preface in the next chapter, bestimmen appears four times in Marx’s original German but only three times in the English translation (the one Williams quotes). And one appearance of determine in the English version actually translates a different German word, konstatieren. Williams does not blame the translator for this discrepancy. "The point here," writes Williams, "is not so much the adequacy of the translation as the extraordinary linguistic complexity of this group of words. This can best be illustrated by considering the complexity of ‘determine’ in English" (Marxism 84). Attuned to the complexity of such groups of words, Williams reads almost as a poet committed to language really used—and, as suggested by his reading of the word determine, language overused and worked over.

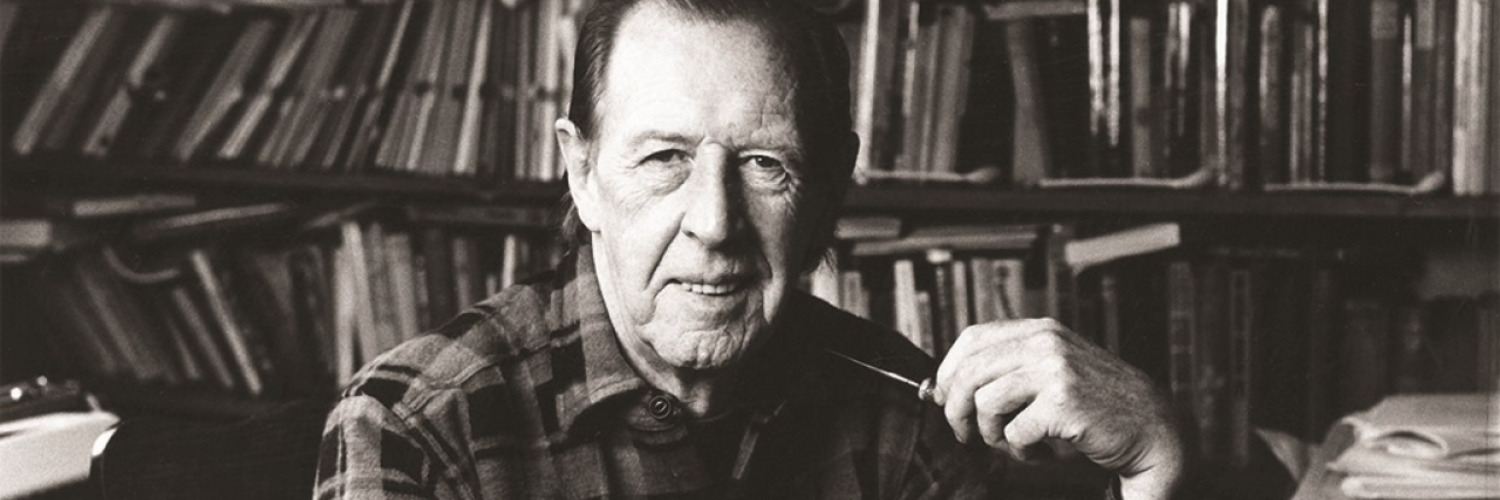

Of the various Romantic writers and poets Williams draws on to advance arguments in his many books, Wordsworth is not always the most important. Samuel Taylor Coleridge plays a more vital role in the early chapters of Culture and Society 1780–1950 and in its sequel, The Long Revolution, for instance. And yet, Williams’s repeated turns to language echo Wordsworth’s famous interest in language "really used by men" (Wordsworth, Selected 281). As Williams writes in the introduction to Culture and Society, "I feel myself committed to the study of actual language: that is to say, to the words and sequences of words which particular men and women have used in trying to give meaning to their experience" (xix). While Williams translates Wordsworth’s adverb ("really") into an adjective ("actual"), he develops Wordsworth’s poetics as advanced in the preface to Lyrical Ballads into a detailed critical method. And Williams’s commitment to actual individual statements over what he calls "a system of significant abstractions" echoes Wordsworth’s distrust of personified abstractions of ideas (Culture xix). At moments like these it can seem that Williams is a determined Wordsworthian.

Of Determined Bounds

If a poor reading of Marx absolutizes one sense of "determination," then a poor reading of Romanticism absolutizes the other (as if Romanticism named nothing other than the systematic assertion of the individual will). I turn now to Wordsworth and the opening book of The Prelude, in which Wordsworth’s poet-speaker poses two related questions: Was I determined (by Nature) to be a poet; and Am I determined (enough) to become one? Wordsworth’s The Prelude, in other words, is motivated by the question of determination, and the word determined appears in the text at two key moments in the first book, once near the beginning where he announces his longing for a "determined aim," and once near the end where he celebrates his having settled on a theme, one with "determined bounds" (Prelude 34, 64). Reading Wordsworth after Williams helps make legible the importance of determination to Wordsworth’s thinking about the self.

Wordsworth opens The Prelude by rewriting the conclusion to Milton’s Paradise Lost. In the closing lines of Milton’s poem, Adam and Eve wonder "where to choose / Their place of rest" after expulsion from Eden; and with "providence their guide," hand in hand they wander (618). Wordsworth replaces Milton’s guide, "providence," with a wandering cloud: "should the guide I chuse / Be nothing better than a wandering cloud / I cannot miss my way" (Prelude 28).

In doing so, Wordsworth negates the possible tragedy of Paradise Lost. Though Wordsworth does not know what guide to choose, there is no tragedy in the choice, for, unlike in Paradise Lost, there is no wrong choice: "Whither shall I turn, / By road or pathway, or through open field, / Or shall a twig or any floating thing / Upon the river point me out my course?" (I.29–32). Wordsworth records that after wondering for two days he arrived at his hermitage and he describes the love that greeted him. He is happy for a time.

At this point, and after some rest, Wordsworth characterizes himself as determined, as interested in determining an aim for himself, though what Wordsworth actually writes is quite complicated: "But speedily," writes Wordsworth, "a longing in me rose / To brace myself to some determined aim" (I.123–24). Characteristically, Wordsworth introduces the importance of individual will via syntax that throws into question the active, individual will. A longing arises in him, he writes, as if the longing were to some degree or other independent of him, as if the longing were not entirely his own. Though grammatically the sentence is not in the passive voice, the subject of the sentence is this longing and not Wordsworth himself, not the first person, as Wordsworth positions himself as the object acted upon. Bracing himself for some determined aim, Wordsworth progresses through Book I worrying over various possible choices for poetic composition, as undisturbed delight gives way to concern over a selection process for a proper poetic theme. As Wordsworth wonders what he should write about to prove his worth as a poet, and as he chronicles the various topics for a great poem he entertains only to dismiss, from some British theme or old "Romantic tale by Milton left unsung" to "some philosophic song" (I.180, 230), Wordsworth famously wonders "Was it for this / That one, the fairest of all rivers, loved / To blend his murmurs with my nurse’s song" (I.271–72)? Wordsworth takes stock and determines that he does not lack a vital soul and is not "naked in external things, / Forms, images, nor numerous other aids" (I.165–66), and yet he still must ask: Was it for this? The poet’s self-consciousness results in a question about determination, about the poet’s determination: Was Wordsworth determined for this? And then, subsequently, and thinking of determined as meaning "persistent," is Wordsworth persistent enough to follow through on the promise? Wordsworth’s poem, in other words, shows his sensitivity to the complexity of determination (as word and concept). And this sensitivity can seem to result in the repeated use of dummy pronouns, as the antecedent for "it" in "was it for this" is famously open and opaque.

When Wordsworth concludes Book I, having found his theme at last, he returns to the opening lines of the poem and figures himself as doubly determined. And the word itself makes a potentially surprising second appearance. Wordsworth replaces the wide range of options introduced at the beginning of the poem—where he wonders whether to follow a road or a pathway, a cloud or a floating thing, and write a romantic tale or some philosophic song—with a single option: "The road lies plain before me. ’Tis a theme / Single and of determined bounds, and hence / I chuse it rather at this time than work / Of ampler or more varied argument" (I.668–71). Wordsworth has settled on his theme, "the story of [his] life," and this theme already has a revivifying force ("One end hereby at least hath been attained— / My mind hath been revived" [I.664–65]). Wordsworth chooses a road that lies plain before him, a road, in other words, somewhat well-travelled—even though one might expect him to follow a less predetermined path. Despite the many ways we associate Romantic texts with the rise of the self-determining individual, the poem carefully anticipates and complicates such a characterization. In choosing a road, Wordsworth’s way is determined; it is before him. And he foregrounds the question of determination explicitly by comparing his theme to a road in describing its "determined bounds." Because the theme has determined bounds, Wordsworth is determined to choose it. If the opening of Book I is a return to Paradise Lost, so too is the end of Book I. But whereas Adam and Eve wander, Wordsworth hits the road. His direction, clearly marked, opens before him. Had Wordsworth followed a cloud or floating thing across an open field, his chosen path would have fit more comfortably within the usual stories one hears about Romanticism (as a celebration of nature, of the individual, of the individual imagination, etc.); but instead of wandering across an open field, Wordsworth chooses a road and, additionally, one that "lies plain before [him]."

Near the beginning of Book I, Wordsworth wonders if he was determined by nature to produce The Prelude; by the end of Book I, he has determined his theme, one with determined bounds, a theme that is not varied. In a sense the one meaning of determination (as fixed) combines with the other, as Wordsworth makes his choice and thereby asserts himself as active agent. He chooses (determines) a theme with determined bounds, and as a result Wordsworth—over the course of Book I—draws together, like Williams later, the two meanings of determination. To borrow Williams’s imagined sentence from Keywords, Wordsworth is determined to be determined. If Raymond Williams hopes to complicate a version of Marxism too enamored of "determinism" by reintroducing the importance of individual will, Wordsworth’s The Prelude complicates a too-simple version of Romanticism too enamored of "determination" as individual will, as he reintroduces the importance of determined (and determining) bounds at the close of Book I of The Prelude.

Passive Voices

I have been focusing on what we might call a lexical problem, but as I have already hinted in my opening paragraphs, I would like to turn as well to syntax and to some of the ways lexical and syntactical questions are intertwined in Wordsworth and Williams. The question of determination from Wordsworth to Williams turns on one’s ability to decide whether the subject acts (determines itself for itself) or is acted upon (is determined by something else). The grammatical, or more specifically the syntactical, corollary to the question of "determination" is something like voice, specifically the difference between active and passive voice, where passive constructions invert normal subject and object noun phrases. In the active voice, the subject of the sentence is also the agent of the action. In the passive voice, the object acted upon becomes the subject, and the agent of the action is introduced belatedly, often in a prepositional phrase. For instance, in the sentence "Wordsworth wrote The Prelude," the subject of the sentence (Wordsworth) precedes and acts upon the object of the sentence (The Prelude). But in "The Prelude was written by Wordsworth," the object acted upon comes first. By inverting subject and object, the agent of the action becomes the object of the sentence. And the object acted upon (The Prelude) becomes the grammatical subject of the sentence. For this reason, writing guides often advise against using passive voice. Famously, George Orwell strongly advises against the passive voice in “The Politics of the English Language,” where he suggests that one should "never use the passive where you can use the active" (119). Of more philosophical importance, especially for an essay that began with the difficult problem of determination, passive constructions show just how easily subjects and objects can be reversed, as the agent capable of acting becomes an object and the object acted upon becomes a subject. In other words, passive constructions show how difficult it can be to determine and stabilize the difference between subjects and objects (the agents who act and the things that are acted upon). Passive constructions also showcase how quickly the agent of the action can disappear from a sentence. In some passive constructions, that is, the agent is left, either accidentally or intentionally, undecidable (as in a sentence like "The Prelude was written"). One famous and much cited example is "Mistakes were made," where the one who made the mistakes, the agent of the action, the rhetorical (if not grammatical) subject of the sentence, goes unnamed. As Orwell argues, such a construction allows those in power to stay in power by strategically disappearing. At moments like this one, the agent is determined not to be determined.

In their related attempts to think the difficult problem of determination, both Wordsworth and Williams repeatedly use the passive voice, as their grammar and syntax raise questions about who or what acts and who or what is acted upon. In the writing of Wordsworth and Williams, it is often difficult to determine who is doing what to whom. For instance, early in the glad preamble to The Prelude and after Wordsworth asserts that he "cannot miss [his] way" for his joy is great, he uses a passive construction that leaves the precise cause of his happiness unknown:

It is shaken off,As by miraculous gift ’tis shaken off,That burthen of my own unnatural self,The heavy weight of many a weary dayNot mine, and such as were not made for me. (I.21–25)5

At first it is unclear to a reader what the antecedent for "it" is, but after a line or two it becomes clear that Wordsworth describes the burden of his own unnatural self, a burden that is shaken off. Readers are then able to reread the sentence as "The burthen of my own unnatural self is shaken off." But even when one learns what has been shaken off, the passive construction leaves undisclosed the active agent (the rhetorical if not grammatical subject).

We know who is all shook up, but who or what has performed the shaking? In this opening example, Wordsworth seems to use the passive voice to deepen the mystery of a miraculous gift. For poetic reasons, Wordsworth does not name, and so leaves undetermined, the agent of the action.

Most relevant to my purposes, Wordsworth employs passive voice in the final verse paragraph of Book I of The Prelude as well, where the question of determination is thematized most explicitly. As Wordsworth draws the first book to a close, he acknowledges that despite continuing difficulties "One end hereby at least hath been attained— / My mind hath been revived" (I.664–65). Who or what has revived the mind? Is it Wordsworth or Nature? Or the act of writing about himself and Nature? The agent of the action is again left unclear, and the effect is particularly Wordsworthian. Wordsworth turns to the passive voice at key moments like these because he does not wish to determine absolutely agents of action. To determine Nature as the active agent makes Wordsworth a passive object. He will have been determined absolutely by an external force. Conversely, to determine Wordsworth himself as the active agent makes Nature a passive object. Wordsworth’s philosophical questions about the relation between poet and Nature lead him inexorably toward the passive voice. Because it is difficult to determine one’s determination, Wordsworth is determined to use the passive voice.

Williams’s own efforts to think determination similarly result in a high degree of indetermination: determination, for Williams, is always "an active and conscious as well as, by default, a passive and objectified historical experience" (Marxism 88). He is interested in determination because it can be difficult to determine adequately when historical experience results from one’s determination (one’s active persistence) and when it results from one’s determination (one’s objectified historical experience). Williams can sound a bit like Wordsworth from “Tintern Abbey” here: as if historical experience were half-perceived and half-created. Wordsworth hopes neither to prioritize poet over Nature nor Nature over poet; and Williams, likewise, hopes to keep both meanings of determination in play. As a result, both repeatedly write in the passive voice.

In a key sentence in which Williams objects to some of the ways Marxism (against Marx, argues Williams) privileges one sense of determination over another to develop a theory of "economism," Williams uses the passive voice conspicuously: "With bitter irony," writes Williams, "a critical and revolutionary doctrine was changed, not only in practice but at this level of principle, into the very forms of passivity and reification against which an alternative sense of ‘determinism’ had set out to operate" (Marxism 86). Williams laments the degree to which Marxism’s focus on passive reification precludes attention to determination as active and conscious. But Williams chooses the passive voice in order to formulate his lament. Marx’s critical and revolutionary doctrine was changed, but changed by whom? Here and elsewhere in his writing, Williams turns to the passive voice as he attempts to rescue "determination" from a determinism that changes active agents into passive objects of cultural and economic forces. Faced with the indeterminate nature of determine in English, and in an effort to draw it out, Williams intensifies a syntactical tic.

For a second example, we can return to another passage I have already quoted. In the paragraph discussed above, in which Williams examines a translation of Marx’s preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy and points to the linguistic complexity of determine in English, the word translators often use to render Marx’s bestimmen into English, Williams writes: "The point here is not so much the adequacy of the translation as the extraordinary linguistic complexity of this group of words. This can best be illustrated by considering the complexity of ‘determine’ in English" (Marxism 84). In the second sentence quoted, Williams leaves blank the rhetorical subject of his sentence, the agent of the action, as the "I" capable of illustrating and considering complexity is left out. And this sentence is illustrative of Williams’s style more generally, for Williams not only leaves out the agent of the action but also the object acted upon: to what does "this" refer to, this "this" that can best be illustrated? An inelegant version of Williams’s sentence might read: "I will illustrate this complexity by considering the complexity of ‘determine’ in English." Williams removes the agent that will perform the action and also leaves "this" to stand alone. Once again, Williams’s syntax raises questions about determination, as Williams leaves much undetermined. He can sound quite Wordsworthian. But just as the point for Williams is not the adequacy of translation, the point for me is not the adequacy of Williams’s style. What interests me most is how often in his writing about determination Williams uses the passive voice. A cursory glance at the "Determination" chapter of Marxism and Literature will show how often Williams repeatedly uses the passive voice and begins sentences with expletives or dummy pronouns (sentences that begin with an empty grammatical subject like the "it" of "it is raining"), a construction that often follows from the passive voice. To quote from sentences early in the chapter that introduce some complexity, especially if one wishes to linger over Williams’ syntax: ‘According to its opponents, Marxism is a necessarily reductive and determinist kind of theory: no cultural activity is allowed to be real and significant in itself, but is always reduced to a direct or indirect expression of some preceding and controlling economic content. . . . In the perspective of mid-twentieth century developments of Marxism, this description can be seen as a caricature. Certainly it is often asserted with a confidence as solid as it is out of date. Yet it can hardly be denied that it came . . . from a common form of Marxism. (Marxism 83)’ Williams presents a caricature of Marxism as determinism that he then acknowledges cannot be denied. He will go on to argue for a less deterministic Marxism. But in the concluding sentences of the above quotation, Williams’s prose features a series of "it" pronouns. The "it" of "certainly it is often asserted" refers to the caricature, though who is asserting it is left open. The "it" of "yet it can hardly be denied" is an expletive, an empty pronoun that serves a grammatical function but has no real antecedent. For Williams, the problem of determination is not independent from certain grammatical and syntactical arrangements, arrangements that make "it," for instance, difficult to determine.

Wordsworth and Williams share not only an interest in the complexity of determination in English, as word and concept, but also an interest in the passive voice and in uses of language that showcase with a certain lightness of touch the ways objects can become subjects and the ways subjects can drop from view, especially in sentences that leave undisclosed and indeterminate the agent of the action.

Determined Determination

It can be hard to tell whether passive constructions determine Wordsworth’s and Williams’s abstract philosophical speculation or whether abstract philosophical speculation determines passive constructions. In general, one might be satisfied with an either/or. But when it comes to determination itself, determining how much determination (as a philosophical question, say) is determined (by grammar, say) can get complicated quickly. How can we know anything about determination if we cannot determine how much our discussion of determination is itself already determined?

When readers bring Marxist cultural criticism and Romanticism into contact, one often senses a need to choose between them. Either Romanticism is little more than an ideology that denies the importance of external economic forces, or it is a vibrant celebration of human potential. In focusing on some of the ways Wordsworth and Williams think determination with and through the passive voice, I have tried for new points of contact. If we take seriously the ways Wordsworth and Williams both foreground passive voice in their writing about determination, we discover stylistic similarities in discourses often perceived to be antithetical, especially when Williams stands in for Marxist cultural materialism and Wordsworth for Romantic idealism. We know that Williams was dissatisfied with certain versions of Marxism and Wordsworth with certain versions of idealism. Both found in "determination" strategies for resisting the pull of familiar isms and both used the passive voice to make a little more restless our attempts to characterize historical experience as either active or passive.

Theory in recent decades has become increasingly proficient at marshalling increasingly complicated philosophical and scientific concepts (let’s call them tropes) in the service of urgent speculation. But some of the most pressing social issues today also hold a grammatical edge, as those urging adoption of l’écriture inclusive in France know well. (In French, an adjective that refers jointly to masculine and feminine nouns agrees only with the masculine one, thus perpetuating [argue protesters] French linguistic patriarchy.) I sometimes worry that theory left grammar behind too quickly as theory courses proliferated in university curricula, even though we always knew (and still know) that there is no style of thought without a grammar. But what if, in place of "No problem in Marxist cultural theory is more difficult, than that of ‘determination,’" Williams had written "No problem in Marxist cultural theory is more difficult than that of passive voice"? What sort of theory would have emerged? For decades, Romanticism has played a key role in the development of theory (or Theory, or theories). I cannot determine whether Wordsworth led me to Williams or Williams led me to Wordsworth, just as I cannot tell whether interest in the question of determination leads to passive voice or if interest in the passive voice leads to questions about determination. It may be impossible to tell. To encounter the impossibility of telling, though, may be one of the only ways to open a new question.