The word brevity appears to derive from a troping of spatial linearity towards the temporal. The earliest examples of Latin brevis refer to shortness of “length in its different directions of breadth, height, or depth”—even to the length “of a circle, as merely a line, and without reference to the space enclosed” (Lewis and Short). The transfer of these spatial senses to temporal phenomena gives brevity an inherent spatiotemporal motility at issue in a long series of questions provoked by the topic of this volume. Among these questions is this one: are all our representations of time dependent on vocabularies of space?

Linked to this is the recognition that the Latin brevis and the English brief acquired, from very early in their histories, distinctly discursive and rhetorical significance. Thus the question of brevity carries important and difficult implications for ongoing debates about the materiality of language.

One obvious place to turn in thinking about romantic brevity is John Horne Tooke’s unfinished dialogic book about language, ÉPEA PTERÓENTA, or the Diversions of Purley. Before I continue with Tooke, let me give a brief indication of where I’m headed. Shelley ordered The Diversions of Purley from his bookseller in December 1812 (Letters of PBS 2: 345), certainly read it, and in the unpublished text we’ve come to call Speculations on Metaphysics dissents sharply from what he takes to be Tooke’s efforts to reduce metaphysics to a “science of words” (Clark 185). Nevertheless, Tooke’s main theoretical concerns, together with his deployment of the figure of Hermes/Mercury, play an oblique but significant role in Shelley’s writing.

The key analytical concept in Tooke’s sometimes brilliant, sometimes erroneous, sensationalist version of universal grammar is abbreviation. The term designates a dynamic that is both structural and historical. It emerges in the opening chapter from two interlocking and post-Lockean principles: (1) “The first aim of Language was to communicate our thoughts; the second to do it [quickly], with dispatch”; (2) “many words are merely abbreviations employed for dispatch, and are the signs [not of things or of ideas, but] of other words” (Diversions of Purley 1: 14). The process of abbreviation involves the derivation of conjunctions, prepositions, adverbs, and the syntagmatic constructs they make possible from nouns and verbs. The cognitive act that supplies the etymological information abbreviation elides is what Tooke calls subaudition.

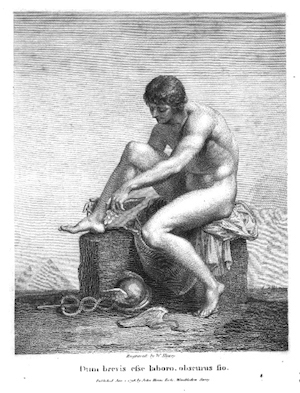

He elaborates these principles playfully as well as ponderously—and here I want to turn directly to the frontispiece of The Diversions of Purley and its connections to the dialogue in Chapter 1 between Tooke and his skeptical friend Richard Beadon.

The engraved figure of a young Hermes seated on a block of stone in the act of either putting on or taking off his winged sandals was designed and executed by William Sharpe, a well-known specialist in line engraving and Tooke’s friend and radical political ally. In broad terms the visual subject is familiar within one of the traditional representations of Hermes. But Sharpe’s figure differs in suggestive detail from this tradition—from the ancient Roman copy of a Lysippan bronze, for instance, as well as from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century versions of the subject in the Louvre. Sharpe’s Hermes is younger, his body more relaxed, the expression on his face more enigmatic as he looks at one of his pairs of wings. The pyramids in the background must allude to the syncretic identification of Hermes with Thoth, the Egyptian god of writing, and thus to Hermes Trismegistus. The caption beneath the image is from Horace’s Ars Poetica 25-6: “dum brevis esse laboro, obscurus fio” [while I labor to be brief, I become obscure].

The bearing of this quotation on Tooke’s analysis and on Shelley’s response to it is ironic. On the one hand, as Zachary Sng argues, “[the] principle of dispatch and its faithful servant, abbreviation, turn out to be curiously opposed . . . to [the] aim of communication.” Brevity often produces obscurity. On the other hand, Sng observes, while the “way of error was thus shown by the god Hermes, . . . the way out of it is revealed by the same deity” (59-60). To this insight we may add that Horace’s words in Tooke’s frontispiece syntactically and prosodically perform the brevity, and not the obscurity, they refer to.

In the Chapter 1 dialogue it is Tooke’s interlocutor Beadon who initiates an indirect commentary on the frontispiece by complaining that “you have . . . no[t] a single word to unfold to us by what means you suppose Hermes has blinded Philosophy” (Diversion of Purley 1: 24). Tooke responds by elaborating the metaphor of “the vehicle of our thoughts,” on his way to declaring that “Abbreviations are the wheels of language, the wings of Mercury” (Diversions of Purley 1. 25). It’s especially the “wings” that make evident why Tooke used the Homeric formula épea pteróenta (winged words) as his title.

B.— . . . You mean to say that the errors of Grammarians have arisen from supposing all words to be immediately either the signs of things or the signs of ideas; whereas in fact many words are merely abbreviations employed for dispatch, and are the signs of other words. And that these are the artificial wings of Mercury, by means of which the Argus eyes of philosophy have been cheated.

H.—It is my meaning.

B.—Well. . . . Proceed, and strip him of his wings. They seem easy enough to be taken off: for it strikes me now . . . that they are indeed put on in a peculiar manner, and do not, like those of other winged deities, make a part of his body. You have only to loose the strings from his feet, and take off his cap. Come—Let us see what sort of figure he will make without them. (Diversions of Purley 1: 26-7)

What interests me here is the connection between Tooke’s demystifying method and the visual:verbal figure of Hermes, whose mythologized bodily identity is made entirely dependent on a non-essential supplement. This supplement—the artificial vehicular wings—is represented in a way that disrupts both the conventional eighteenth-century image of language as the clothing or veiling of thought and the transcendental image of language as embodiment or incarnation. We might (somewhat tendentiously) call the analytical method that emerges from Tooke’s figure of Hermes a hermeneutics of abbreviation.

Hermes’ winged sandals are Tooke’s figure for abbreviation-as-speed, for a discursive brevity understood not primarily as conciseness or compactness (as in the lines from Horace) but as sheer rapidity, quickness, “dispatch” (the Lockean term he uses repeatedly, with its implications of communication and of elimination). Speed may of course produce brevity—but it doesn’t do so necessarily: Shelley’s evocations of speed sometimes go on for a long time, for long stretches of verse. For Tooke, abbreviation is not a discursive phenomenon of parole subject to the agency of particular speakers or writers; it is an aspect of langue as historically evolved system. Tookian brevity is primarily a matter of syntactical grammar and only secondarily a function of phonetic or graphemic duration.

There is, however, a persistent problem with Tooke’s conviction that “the composition of ideas” is “merely a contrivance of Language” (Diversions of Purley 1: 37) —or as Hans Aarsleff summarizes it, “that the operations of mind are really operations of language” (51). And this problem has specifically to do with abbreviation-as-speed. The development of thought is identical with the development of language—and yet, Tooke says, the speed of the former will always exceed the speed of the latter: ‘Words have been called winged; and they well deserve that name, when their abbreviations are compared with the progress which speech could make without these inventions; but, compared with the rapidity of thought, they have not the smallest claim to that title. Philosophers have calculated the difference of velocity between sound and light: but who will attempt to calculate the difference between speech and thought! What wonder then that the invention of all ages should have been upon the stretch to add such wings to their conversation as might enable it, if possible, to keep pace in some measure with their minds. (Diversions of Purley 1: 28-9)’ Language retains an otherness to thought here that, by implication, must have to do with what Saussure refers to as “the linearity of the signifer,”

which persists in differentiating language as discursive system from the mental life it makes possible and otherwise constitutes.

Shelley’s reading of Tooke would have foregrounded this problem, I suspect, and would have led him to understand abbreviation-as-speed rhetorically as well as grammatically. Language is “arbitrarily produced by the Imagination and has relation to thoughts alone,” Shelley writes in the Defence (Shelley’s Poetry and Prose 513), and yet in British Romanticism’s best-known paradigm of inspirational and compositional brevity, “when composition begins, inspiration is already on the decline” (531). As a consequence, poetry must continually renew and reawaken the metaphoricity of language as a counterforce against its deteriorating into a system of “signs for portions or classes of thoughts” that is “dead to all the nobler purposes of human intercourse” (Defence 512). “[T]he copiousness of lexicography and the distinctions of grammar,” Shelley insists, “. . .are merely the catalogue and the form” of language that remains “vitally metaphorical.” Shelley’s attraction to swiftness, rapidity, and quickness might be read, then, as a rhetorical rewriting of Tooke’s grammatical abbreviation-as-speed. Where Tooke in his way disfigures Hermes to isolate the function of his wings, Shelley may be said to refigure the ties of these “artificial” wings to Hermes’ mythographic body.

Such refiguration is at work in Shelley’s translation of the Homeric “Hymn to Mercury” (1820), parts of which read as an allegorizing of poieisis, including lyric temporality, in its Hermetic and Apollonian modes.

Rhetorically the poem capriciously (in some moments maliciously) narrates and dramatizes the first day of Mercury/Hermes’ life: twice he says explicitly (in English as in Greek) “I was born yesterday” (ll. 363, 497). Much of the poem depends on an extreme and comic durational abbreviation for which we might adapt Mieke Bal’s term “temporal foreshortening” (144). On his way to stealing Apollo’s cattle, the un-infant Mercury comes across a tortoise, “Moving his feet in a deliberate measure” (l. 30) and is instantly inspired to an act of gruesome creative violence. With a chisel “He bore[s] the life and soul out of the beast” (50) and turns its shell into the sounding-board of the world’s first lyre. Shelley makes this scene of lyric origination a moment of fiercely sadistic “dispatch”:

Not swifter a swift thought of woe or wealDarts through the tumult of a human breastWhich thronging cares annoy,—not swifter wheelThe flashes of its torture and unrestOut of the dizzy eyes—than Maia’s son5All that he did devise hath featly done. (ll. 51-6)

In his book on Shelley and translation, Timothy Webb observes that the “image of the wheel with its flashing spokes does not occur in the [Greek] original” (Webb 99). But the wheel image does occur in connection with the figure of Hermes’ speed in Tooke’s The Diversions of Purley where, as we’ve seen, it instantly gives way to wings as a metaphor for the speed of grammatical abbreviation. In Shelley’s translation, via a negative simile, Hermes/Mercury fashions the artifact of lyric energeia by transmuting slowness into swiftness in a flash of perverse brevity.

Shelley’s allegory of sonic intensity and duration turns towards a mercurial materiality of the letter in Mercury’s confrontation with Apollo over the theft of his cattle. To escape detection Mercury mysteriously makes his own and the cattles’ prints in the sand turn backwards, “So that the tracks which seemed before, were aft” (l. 98; Shelley is translating the phrase íchni apostrépsas in l. 76 of the Greek text). He then discards his (already winged?) sandals and substitutes for them sandals improvised out of tamarisk leaves that further obscure his footprints. The figure of linguistic signs as footprints is recurrent in Shelley and carries both inscriptive and tropological implications. In the “Hymn to Mercury” the image is comically played out when Apollo hauls Mercury before Jove and complains of (among other things) “the double kind of footsteps strange”:

His steps were most incomprehensible—I know not how I can describe in wordsThose tracks . . . (ll. 457-59)

The entire confrontation is framed by Mercury’s invention of the lyre and brought to a close by his passing on to Apollo an instrument imbued with mercurial rapidity, exploitation, and deception as well as with the potential of sublime pathos.

Apollo is eventually undeceived by Mercury’s cryptic traces. But he has come to be indebted to Mercury’s artificial gift of lyric energeia—a quick, opportunistic performative brevity that exploits thought’s vexed interdependence with its material articulations. As Apollo launches into a concluding encomium of the “little contriving Wight” (l. 585), he is represented as doing so in Mercury’s own terms: “His words were wingèd with his swift delight” (l. 581).

With the concluding exchange of lyre and caduceus, though, we may be left wondering about the terms on which mercurial/hermaic brevity can survive its normalizing Apollonian appropriation.