Introduction: We Fight for Grass

What may be the first appearance of “political ecology” in print offers no distinct definition or theorization. Yet Frank Thone’s little think piece entitled “We Fight for Grass,” which appeared under that heading in the Science News Letter of January 5, 1935, does articulate a strange, age-old parable of colonial avarice and climatic revenge. The topos long predates both the inauguration of the natural science of “ecology” in the 1860s and its self-conscious politicization in the 1970s, not to mention the splashy advent of a quite different sense of “political ecology” in (post) humanistic theory by way of Jane Bennett’s 2010 monograph, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Visions of what might be called “ecological retribution” — and their utopian counterpart, “ecological jubilee” — were to be the subject of this essay, for the sake of ecocriticism and Romantic “political ecology” avant la lettre, long before I stumbled upon a variant here, at one minor, modern origin of the phrase. Yet its presence, I think, promotes Thone’s much-dismissed “We Fight for Grass” into a revealing emblem for the ongoing challenge of “political ecology” in the text-based disciplines and a concise introduction to the present essay.

In Thone’s 1935 iteration of “political ecology,” the fantasy of ecological retribution arrives at the height of an unwieldy analogy that compares the incursions of Imperial Japan in Outer Mongolia to “the Indian Fighting days of our own West” (14). While “to be sure, there are differences,” Thone boils both conflicts down to an age-old antagonism between settlers and nomads: native peoples who “fight for grass” — pasture for their ruminant food sources — against the conquering plowshares of an “emergent empire” (14). The terms of the analogy are thus technically mythic even before the author actually compares Mongolian horsemen to “Centaurs” (14). The toil of tilling the soil divides fallen life from Paradise in Judaeo-Christian theology and the Golden Age from the rest in Greco-Roman cosmogony; Reformation theology and Enlightenment stadial historicism redefined such declension as progress and ranked human societies accordingly. None of these mythic backgrounds are incidental to the present inquiry. But what matters most is the moral climax of “We Fight for Grass,” when Thone suddenly pivots to the Dust Bowl then afflicting the North American prairies. His political ecology casts this catastrophe as a modality of attenuated, indigenous revenge: ‘The Indians fought for grass. They lost. The plow broke sod farther and farther westward, until in the mad, wheat-hungry years of the World War grasslands that never should have been turned over at all were broken and put into grain. Then came drought, grass-hoppers, dust storms; the Indians were in part avenged. Now we seek to replace the vanished grass. (14)’ At a distance of 85 years, the ideologies in play make easy targets. Grasslands “turned over” by an agentless “plow” elide their seizure through genocidal acts of “Indian Removal” (juridical, military, and biopolitical) that the author will neither query nor name. “We seek to replace the vanished grass,” Thone concludes, yet fail to imagine reparations for the (putatively) “vanished” people, let alone grasp how the two projects would be inseparable. Though a tone of regret replaces that of triumph, Thone’s grass-up, ecological retelling of political conflict leaves the fatalist logic of Manifest Destiny and its myth of the Vanishing Indian intact.

Yet it is precisely this heady mix of ecological regret and ethnocultural unaccountability that may make Thone’s New Deal “political ecology” a still-pertinent emblem for the state of our art. Rewriting episodes of imperial conquest from the angle of the grass, the effort prefigures now familiar forms of an ecologically motivated “nonhuman turn” and their increasingly notorious political shortcomings when it comes to those Sylvia Wynter names “Man’s human Others” (Wynter and Scott 174). Influential new materialist, object-oriented, posthumanist, and Anthropocene theories have been charged justly with “resounding silence” on matters of race and colonial history, above all by scholars in Black and critical ethnic studies whose thought, by force rather than belated epiphany, has proceeded in proximity to categories like animality, thing-hood and the land (Z. I. Jackson 216; Karera, 34, 47). The elision of pertinent non-white, non-Northern expertise marks the recent genealogy of “political ecology” as well. Giving the term new life in Vibrant Matter, Bennett neglected to acknowledge the the full-fledged academic discipline that already bore the same name. Centered in the study of the global South, Political Ecology was born among mid-century decolonization struggles and infused the purportedly apolitical natural science of ecology with the insights and methods of critical geography, Marxian structural analysis, cultural ecology, peasant and agrarian studies, and systems and dependency theory, frequently in open opposition to Third World development policies and in open alliance with indigenous and peasant movements.

What is the connection between eliding minoritized people and thought in some variants of “political ecology” and the tendency to figure climate catastrophe as a modality of their revenge? In what ways does “Anthropocene” discourse license again, and with all scientific rigor, an understanding of the weather as payback for crimes of history? Can such moralization constitute anything other than repressed theology? The theological echoes in this essay's key terms, ecological "retribution" and "jubilee,” are meant to welcome this latter question. The following contribution to the problem of “political ecology” seeks to explore this ideologically fraught mode of merging, or submerging, human histories of exploitation into the action of (also exploited) terrestrial elements — including some improbably radical, utopian variations on the theme.

Limits of time and training do not permit me to remedy the missed encounter between the two materialist formations of “political ecology” sketched above — the one a critical natural and social science, the other a posthumanist ontology of relation — by properly interdisciplinary, hemispheric means. What I can do is plumb my European Romantic archive for the site that prefigures this encounter with the greatest intensity, soliciting a practice of reading informed by critical ecologies of race. This site is the highly vulnerable, even confused conjuncture between materialist natural philosophy, Jacobin internationalism, antislavery and commercial empire bodied forth as botany (c.f. “We Fight for Grass”) in Erasmus Darwin’s 1791 epic, The Economy of Vegetation. Exemplifying the wider logic of “ecological retribution” and “ecological jubilee”, Darwin’s materialist epic and associated satire envision elements of exploited earth and dispossessed people conspiring to avenge or overthrow regimes of colonization, expropriation, and enslavement. I take seriously the way this problematic gesture contests, at a stroke, the progress of empire, the rule of “natural law,” and normative expectations about which kinds of terrestrial beings are capable of moral and political action.

The first part of this essay locates the poetic and political roots of Jacobin ecological jubilee in Golden Age pastoral, with that tradition's peculiar credulity regarding the political partisanship of other-than-human natures. Darwin’s engagement with this tradition is never finally dissociable from the English Enlightenment ideologies of which his “Lunar Society” circle formed the liberal and dissenting vanguard, including familiar and still fatal forms of techno-utopian optimism. Yet I attempt to isolate that aspect of Darwin’s techno-pastoral that exceeded such mystifications and apologetics, frightening his contemporaries with a vision of communal luxury that extended past both the rights-bearing category of the citizen-subject and the purportedly universal community of humanitarian sentiment, into the (supposedly) extra-political terrain of the earth.

Turning from ecological jubilee to ecological retribution, the second part of this essay delves into the most geological and abolitionist canto of Darwin’s Economy of Vegetation, teasing out the overdetermined connections between racialized blackness and the energetic humus of appropriated earth that Darwin’s poetry confusedly mobilizes. The section focuses on Darwin’s repeated engagements with the period’s most iconic antislavery icon, Josiah Wedgwood’s mass-produced cameo of a pleading slave in chains. I argue that Darwin’s due diligence to the extractive sources of both industrial manufacture and geological knowledge combines with his “relief poetics” — a compositional commitment to bestowing figure on the material that usually passes for ground — to issue distinctly anti-humanitarian and illiberal incitements to vengeance against slavery and colonization. In the militant visions of ecological retribution that ensue by the close of this “Earth Canto,” human and inhuman victims of this process collaborate to inhume the transatlantic traffic known as “The Inhuman Trade.”

In contrast to the new materialist vogue for leveling hierarchies in the domain of ontology, I argue, Darwin’s Economy of Vegetation belongs to the prehistory of ecological reckoning with social class, racial caste, and colonial history — that is, with the differential distribution of harm, culpability, resistance, and reparation that is the substance of ecological justice. Taken together, the Jacobin and abolitionist dimensions of his materialist “economy of nature” illuminate, in their intersection, both the ideological and the utopian horizons of a genuinely political ecology.

Jacobin Pastoral, or Plants Without Plants

After several decades of restitution by historians of literature and science, Erasmus Darwin’s encyclopedic oeuvre at last requires no general introduction in a venue such as this.

Despite the long-term triumph of a rival Romantic aesthetics that noisily broke with the doctor-poet’s prosody, philosophy, and politics, The Botanic Garden (1791) is now recognized quite simply as “the most popular and the most controversial nature poem of the 1790s” (Bewell Natures 53). The poem in fact comprises two epic, didactic parts, The Economy of Vegetation and The Loves of the Plants.

Though the Loves’ racy animations (indeed, animalizations) of plant sexuality will reenter this inquiry, our ultimate focus is The Economy of Vegetation. Following the Lucretian trick of shifting focus from single, bounded, perceptible bodies to the plural, subliminal, elemental media that pass through and between them, The Economy of Vegetation treats botanical bodies — in so far as they metabolize water, light, earth, and air — as privileged organs for the disclosure, the making phenomenal, of every chemical and energetic interchange on the globe. In each of the poem’s four Cantos, the “Goddess of Botany” summons one elemental constituency (Earth, Air, Water, and Fire, respectively), and proceeds to chronicle the action of its members “as they may be supposed to affect the growth of vegetables” (v).

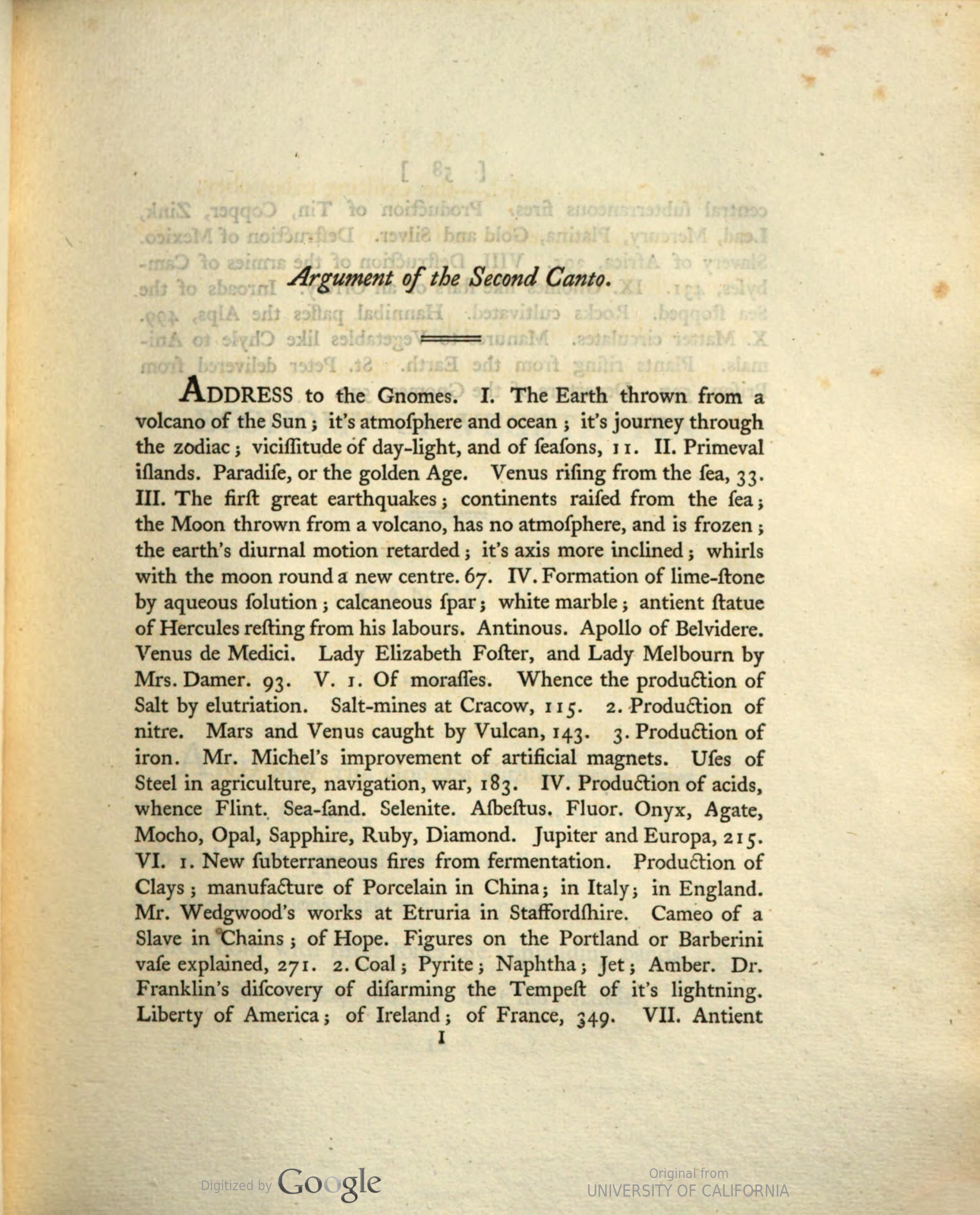

At this point, the staggering array of topics that bear upon plant life and love in this poem comes into view. As we can see from “the Argument” of any given Canto (Figure 1), the poem leaps from chemical to mythological, natural philosophical, technological, and even world-historical registers, compassing celebrations of the “Liberty of America; of Ireland; of France” and denunciations of the slave trade and the Spanish colonial “Destruction of Mexico” (57-58).

Figure 1. “Argument of the Second Canto.” The Economy of Vegetation; Part I of The Botanic Garden (1791). Courtesy of HathiTrust.

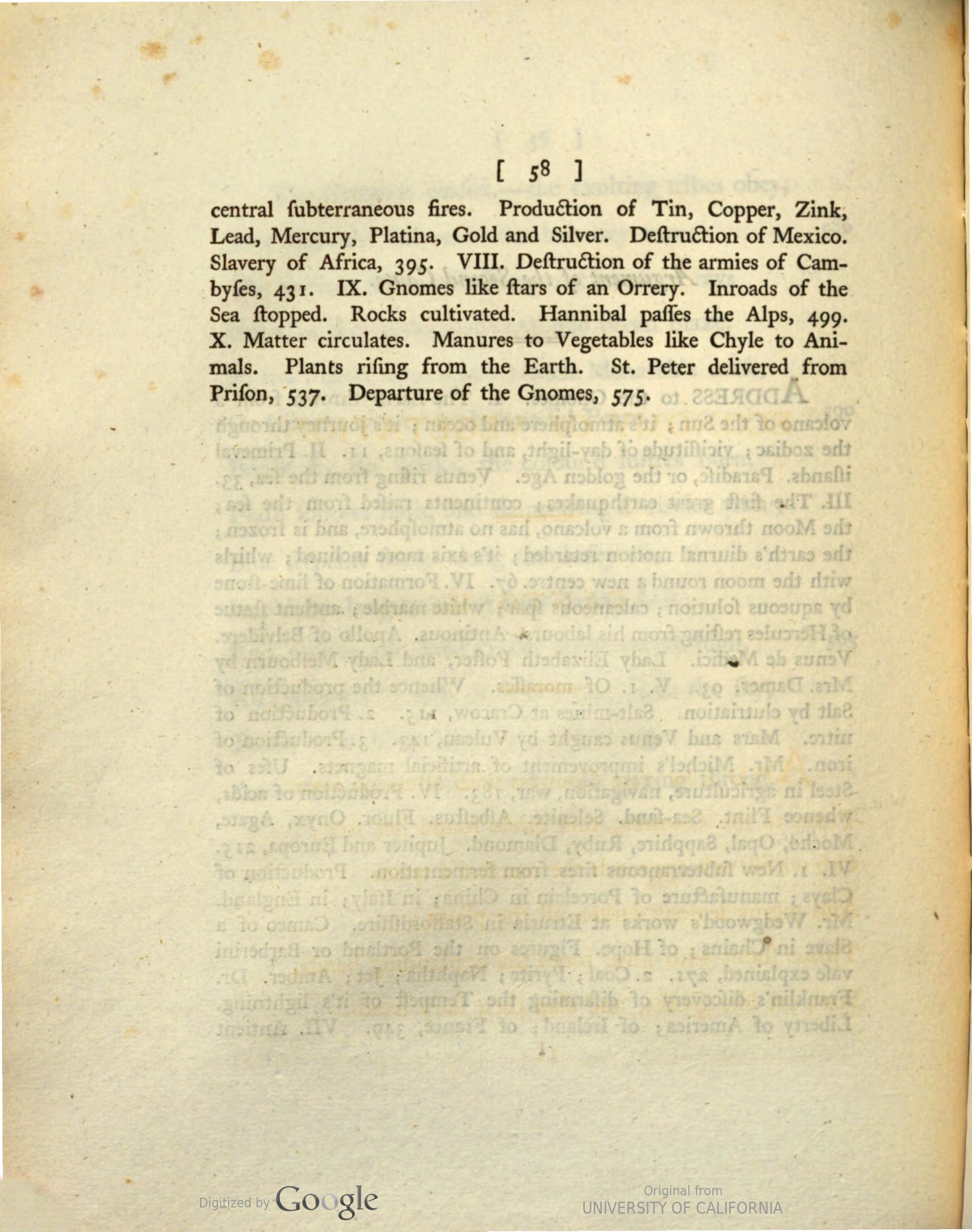

Figure 2. “Argument of the Second Canto.” The Economy of Vegetation; Part I of The Botanic Garden (1791). Courtesy of HathiTrust.

My aim in this section is to take seriously (if no less comedically!) the pertinence of revolutionary, anti-colonial, and abolitionist causes to an Economy of Vegetation, right up to the absurd, limit-possibility of politically partisan vegetables. Previous scholars have shown that Darwin’s critics on the British right provide acute diagnoses of the political and aesthetic threats his botany posed in the 1790s.

Following their lead, I examine visual and verbal parody of his floral politics, drawing new attention to the way Darwin's hostile contemporaries fit his work into a tradition of utopian pastoral writing in which other-than-human beings indeed evince surprising political proclivities.

Alan Bewell’s groundbreaking 1989 article on “Botany as Social Theory” first drew English Romanticists’ attention to James Gillray’s 1798 cartoon “New Morality,” (Figure 3; Bewell 1989), published in the Anti-Jacobin Magazine and Review.

Figure 3. New Morality; or The promis’d Installment of the High-Priest of the Theophilanthropes, with the Homage of Leviathan and his Suite.” Folding plate in the Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine, Issue 115, published August 1st, 1798 by J. Wright, no. 169, Piccadilly. Courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum.

The piece is an extraordinary visual condensation of the culture war (from 1793, also an actual war) excited in Britain by the French Revolution. There is much late-Directorate topical specificity on evidence here: a nightmare scenario in which President Revelliere-Lepaux, “high Priest of the Theophilanthropes,” has been installed in St. Paul’s Cathedral under the craven auspices of “Justice,” “Philanthropy,” and “Sensibility,” ushered in by a Napoleonic Leviathan (the obese amphibian on the left).

Figure 4. “Closeup of Gillray’s “New Morality,” revealing a bewigged figure (E. Darwin?) carrying a basket of flowers labelled “Zoonomia; or, Jacobin Plants.”" Courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

The invading monster has an English face, that of the Whig Duke of Bedford, and carries other prominent Whig politicians on its back; they are wafted into London on a frothy tide of revolutionary fervor that had, at least since Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), been figured as intoxicating liquor bubbling across the channel. A print-media “cornucopia of ignorance,” labeled with the names of a number of liberal press outlets, echoes the beast’s fat form: it overflows with ten years of English left-ish writing, from Coleridge and Southey to Priestley, Tooke, Godwin, and Wollstonecraft.

Bewell urged Romanticists to zero in on the tiny flower-seller (Figure 4) in the distant middle ground of the image, just before the ad hominem caricatures of political figures and their works fade into an anonymous popular mob. The flowers in the seller’s basket are blossoming into a riot of bonnet rouges, and the little label beneath reads “Zoonomia” — the title of Erasmus Darwin’s medical magnum opus on animal life (1794–96) — followed by the perfectly incriminating subtitle, “Jacobin Plants.” “Zoonomia . . . or Jacobin Plants”: pithy proof that Darwin’s botany was perceived as a partisan endeavor in the 1790s and of whose side it was on. Bewell moved outward from here to reevaluate botany in the period as the locus of a “radical form of pastoral poetry”. Thanks to his reading and others, we now understand Darwin’s The Loves of the Plants as Exhibit A for an English libertine botany that mobilized plant sexuality as a polymorphically perverse challenge to the contemporary mating rites of British humans ("Jacobin Plants" 132). Darwin’s “flowery porn,” as Tristanne Connolly put it, outraged conservative critics, not least because the pleasures of botanical reading were so frequently enjoyed by women.

Yet it is less clear how a pastoral that is radical in the sphere of gender and sexuality connects to the adjective “Jacobin” that would seem to stand instead, in Gillray’s cartoon and in the English conservative imagination, as a loose cipher for a somewhat different social threat — that of popular, transnational Revolutionism. Visually, the blooming Liberty Caps in Darwin’s basket amplify the raised arms and open mouths of a threatening, jubilant mob.

Let’s, then, draw out the cartoon’s stranger and more hilarious accusation that Darwinian botany is a botany in which plants take a political side, sporting or sprouting Phyrigian caps as partisans of liberty. Might other-than-human natures have moral and political prowesses and preferences, in addition to, or even as a subset of, their Loves? Here it is as if, to quote that later, flower-powered, libidinal revolutionist, Herbert Marcuse “Nature, too, awaits the Revolution” (74).

Reading Gillray’s image against itself, we can see that it bears hostile witness to something very like this thesis: not only flowers, but fish, fowl, reptiles, amphibians, and other mammals swell the ranks of the revolutionary invasion. A metamorphic front of half-human chimera (avian, simian, reptilian . . . asinine!) conveys the purportedly degrading message that it is the animal in human beings that drives their transnationally militant works and acts (in the guise of Jacobin “phil-anthropy”).

We are supposed to laugh, of course, but also to be afraid. In the eyes of his critics, it seems, Darwin and his crew of enthusiastic, polymathic, dissenting Enlightenment savants — the Lunar Society, as they called themselves — represented a dangerous, Francophilic form of socially Utopian naturalism that drew force and authority from the wider, para-juridical domain of the earth. This position is clearly part — but not, I think, a well-grasped part — of the long-term rise of “natural right” political philosophy in general and of Jacobin “natural Republicanism” in particular (Edelstein 1–25). It is also clearly connected, as Devin Griffiths has recently argued, to Darwin’s increasing notoriety as a theorist of biological evolution.

Yet both these orientations would read the flora and fauna in this image as allegories for human degradation. How might we instead thicken the notion of “radical pastoral” to account for the ridiculous and/or dire possibility of multinatural revolutionism found in Darwin’s representations of plant animacy and love?

Another brilliant parody helps specify the logic — or the fantasy — that keeps turning Darwin’s Botanic Garden into a botany of liberation. Published anonymously four years prior to Gillray’s cartoon, The Golden Age: A Poetical Epistle from Erasmus D--n, M.D. to Thomas Beddoes, M.D. (1794) purported to be written by Darwin to his friend and collaborator Thomas Beddoes, a famous experimental chemist and notorious apologist for the September Massacres.

More outrageous, even, than “Jacobins,” The Golden Age hails Darwinian plants as veritable sans-culottes. (Cheekily mistranslated to imply, yes, plants without pants.) In fact, The Golden Age attempts to expose the whole Darwinian project of versified botany as an awkward, obvious attempt to clothe the “broad,” “brawny” butts of the Paris street in decorous poetic breeches. “Attend,” calls the poem’s pseudo-Darwin to his sans-culottist comrade, “While in Rhyme’s Galligaskins I enclose / The broad posteriors of thy brawny prose” (B2).

Like Gillray’s cartoon, The Golden Age parody singles out for special ridicule the theme of nonhuman natures collaborating and rejoicing in the Revolution. “Skip, skip ye Mountains! Forests lend your Ears!,” calls “Darwin (5).” For under the rule of “red-capt Liberty” and “fair Philosophy” that the poem heralds, tongue-in-cheek, a two-fold revolution transpires (5, 4): while the human sans-culottes level their social hierarchy “to the mean muck of low Equality,” the curse of human labor relaxes, and other natures assert their own technicity (11). Plants spontaneously metamorphose into luxurious foodstuffs and manufactures, much to the delight of the rural and urban poor, who are left idle by the newfound productivity of louche, transgressively animate Darwinian vegetables. In a return to the effortless luxury of the mythic Golden Age, stock Georgic characters like the busy dairymaid swiftly regress to lazily gathering “Rich Cream and Butter from [a] herd of Trees” (10). By the climax of this part of the poem, plants have assumed the manufacture of complex commodities and luxury goods: “Tallow Candles tip the modest Thorn, / Candles of Wax the prouder Elm adorn!”; atop another grove, “Where leaves once grew, now periwigs of Hair!” (7).

The most obvious target of the parodist’s extravagant vegetable grotesques is a certain form of techno-scientific hubris. Darwin, Beddoes, and their Lunar Society cohort were at the forefront of the coal-, steam-, and expropriation-powered industrial modernization of the English Midlands; at the dawn of an “Anthropocene” age frequently dated to their precise generation and social set, they helped pioneer a now familiar and still feckless variety of techno-utopian futurism. In places in The Botanic Garden, Darwin apostrophizes steam power, prophecies air travel, and projects geo-engineering as a modality of climate control.

Taking as an epigraph one of Beddoes’s particularly enthusiastic speculations — “May we not, by regulating the vegetable functions, teach our Woods & Hedges to supply us with Butter & Tallow?” — the parody is out to caricature Lunar readiness to meddle in the natural order of things as well as to prophecy the monstrous consequences of a notably Godless faith in scientific miracles.

This rather familiar form of anti-Promethean caution against Beddoes’s and Darwin’s visionary experimentalism is not entirely fair.

But what I wish to emphasize instead is that the parodist also picks up on, and exaggerates to the point of caricature, a different, though perhaps equally delusive and damaging, form of techno-utopian ecology in Erasmus Darwin’s sans-culottist botanical poetry. For beyond the epigraph in this instructive spoof, cessation of labor becomes its crucial theme: pastoral otium in the key of freedom from toil, carrying with it release from the exigency to transform, combat, coerce, or exchange other natures. What humans (specifically, the “frisky French” and their English admirers) do in The Golden Age parody is violently revolutionize their social order, delivering the “gigantic blow” that lays Royalty, Monarchy, Ministry, Bigotry, Slavery, and God “low” (12–14). What other natures do, in the solidarity that the parodist sarcastically calls their “happiness” and “triumph,” is pitch in to resolve the resultant crisis in production. Their generous, generative metamorphoses realize and surpass that fundamental demand of the sans-culottes — "Equality and Bread!” — which itself pushed past the domain of liberal political rights and into the realm of “animal” need (Soboul 43–52; Simmons 1–12). The Golden Age epistle culminates in a materialist burlesque in which the people Burke famously characterized as a “swinish multitude” party with an actual multitude of pigs (among other flora and fauna), flourishing on uncoerced plenty and rejoicing in their general “nudity of Breech!” (15, 12)

Sketched here in negative, unflattering caricature, then, would seem to be a vision of not-merely-human “communal luxury” that, as an ecological ethos, would be deliciously, improbably predicated on working less

Focused on setting their social relations in order, the Europeans in the poem relent in their intensive transformation and domination of the (rest of the) natural world. And rather than occasioning a reversion to wilderness or (ig)noble savagery, this cessative ethos gives place to the ingenuity, artfulness, and technics of natures not usually credited with such powers. Deriving the latter vision from Darwin requires little hyperbole: The Botanic Garden, as we shall see, everywhere attributes technical and cultural ingenuity to flora, in extension of their powers of erotic and physiological transformation. Belonging, as The Golden Age parodist emphatically signals, to the proto-utopian genres of Golden Age myth, pastoral poetry, and belly-centric Land of Cockaigne folklore, the Lunar Society’s experimental philosophy and poetry thus hazards the insane, intoxicating possibility that the supposedly immutable “natural law” said to govern the non-human realm may be as fungible as our “positive” and “civil” law. What if scarcity, competition, and toil were “necessities” not of Nature but of liberal political economy, laws of a zero-sum system transposed (and enforced) upon an Earth quite capable of behaving differently? If the rules of the oikos were changed, do we really know what other natures would do? On what grounds do we assume that moral, cultural, technical, and political capacity in nature actually begin and end in those beings currently overrepresented as rights-bearing citizens and subjects of moral sensibility? “Shout, shout, ye Meads! . . . ye Corn-fields, raise your happy heads!” (15)

Lest deriving this eco-utopian vision of multinatural jubilee from its derisive caricature seem farfetched, consider that the apocryphal Golden Age epistle seemed so very like something Erasmus Darwin would write that he felt compelled to publicly disavow authorship in the Derby Mercury (King-Hele 250). Though hardly a subtle piece of work, the anonymous parody persists in “the odd distinction of having been read ‘straight,’” and it continues, to this day, to be misattributed to Erasmus Darwin in some library catalogs and criticism (Faubert 454; Reiman xii–ix; Priestman 199n12). Martin Priestman convincingly suggests that an embarrassing similarity between anti-Jacobin parodies like The Golden Age and an epic that Darwin actually had underway in the late 1790s — a poem in which, according to extant notes, “Liberty returns, and leads the golden age” under the aegis of “mild Philosophy” and Nature in the Lucretian shape of “Immortal Love!” — may have motivated Darwin to abandon that genuine Golden Age project (Priestman 261, 193-216). Satire and sincerity, original and parody, thrilling possibility and risible absurdity blur so thoroughly in the reception of such utopian political ecology that one begins to suspect that — as with the term utopian itself — the assumption of derogatory or aspirational connotations, the placement of the line between vision and farce, reveals less about the text itself than about a given reader's degree of attachment to the present order of things.

The Golden Age parody will not let readers forget that there is classical precedent for all this. The poem everywhere references Virgil’s fourth, “messianic” Eclogue, notable for infusing Golden Age myth into the pastoral mode and for transposing that Age from the mythic past to the imminent, political future.

What matters about this version of pastoral as a means to capture (and skewer) Darwin’s visionary naturalism is that Virgil’s Eclogue borrowed the stirring, Golden Age topos of an unforced, unstinting earth — “the fruitful earth unforced bare . . . fruit abundantly and without stint” to mortals “free from toil and grief" — and cast this condition of uncoerced terrestrial luxury as subject to political restitution (Hesiod 117–18, 113). An encomium to his patron Pollio, consul at the time of composition, Virgil’s poem augurs the return of the Golden Age under his stewardship, prophesying the birth of a divine ruler whose advent brings the very earth to pour forth gifts of flowers, fruits, milk, and grain. The anonymous author of The Golden Age satire of Darwin suggests that the Lunar Society cohort likewise expects the wholesale “renovation of the world," albeit "under the benign influence of French Freedom” (5n).

And here, in fact, is the first political-ecological feature to mark the classical Golden Age tradition associated, by the 1790s, with experimental utopianism and Jacobin internationalism: the notion that plants and animals and winds and waters will participate in a new political dispensation, altering the very face of the earth. On the horizon of the faltering republic, Virgil’s fourth eclogue forecasts a form of theologico-political expiation felt deep into the earth: an alteration that would “free the lands from lasting fear" (Lee 57; Virgil 13–14).

While the Golden Age renews under the rising sign of empire in Virgil, Ovid’s version harks back to an anarcho-communism of terrestrial elements: the earth (humus) “had been a common good, one all could share,” “just like the sunlight and the air” (Mandelbaum 8; Ovid 1:135–36). Justice was immanent in such an earth, as we learn when She flees it (in person of the goddess Astraea, 1:150); or which we knew already, since everything and everyone moves “uncompelled” (inmunis) but righteously (Mandelbaum 6; Ovid 1:101). When Ovid writes that “the Age” — not just its men — cultivated faith and rectitude of itself, without law, and without judge or protector, he gathers persons, animals, plants, and planet together, in an epoch of unforced generativity and righteousness (Ovid 1:89–90).

Though their political valences differ diametrically, then, both the Ovidian and the Virgilian strains of Golden Age myth share the vision of a nature that answers to justice, rather than necessity. They also share in the enactment of a poetic reprieve from the labor of coercion that is felt both by those who work the land and the land that they work, together: “the soil will suffer hoes no more, nor vines the hook” (non rastros patietur humus, non uinea falcem) (Lee 59; Virgil 40). Yet Virgil also presses to the point of irony, perhaps to the point of transparent fantasy, the Golden Age vision of spontaneous luxury and worklessness without privation. As the Eclogue’s landscape “spontaneously” overflows with goods that conform to aristocratic taste, Virgil — and Darwin’s parodist after him — manages to underscore the eye-brow-raising convenience for (certain) humans of that which the earth is said to give freely (sponte sua) in her golden mood.

Most hyperbolically, rams and sheep turn themselves rich colors - purple, saffron, scarlet - gamely obviating the need to dye their wool or skins. In Virgil's "technicolor" animal skins (Rosenmeyer 217), the later parodist of Erasmus Darwin finds his mark: where "nature" is poetically induced past fruiting and farming into textile manufacture and manipulation, there is an emblem for the hubris of experimental philosophy and textual artistry at the dawn of the Industrial Age.

The parodist clearly sees a distinction without a difference between trying to intervene technically in plant fertility (to "regulate the vegetable functions") and the Golden Age vision of their spontaneous technicity that he summons to ridicule that project (B2). The latter is ideological cover for the former, and both instantiate what Anti-Jacobin satirists on the British right would soon distill as the core Darwinian/Jacobin fallacy: "Whatever is, is wrong." The ethos not only inverts the quiescent motto of that responsible couplet artist, Alexander Pope, but also constitutes a dangerous and unchristian suggestion to the rabble that labor is not their lot in this life.

For, in fact, in the shadow of Virgil’s pastoral irony, the earth’s supposedly unforced freedom can appear to differ precious little from her forcible transformation: do not other natures live to serve human desires in Golden Age ecology? Celebrating their creative powers à la Darwin (like celebrating their “resilience,” in a contemporary idiom), may be little more than an alibi for subjecting them to every serviceable transformation.

From a Marxian perspective, meanwhile, is not nature’s productive “automatism” in the Golden Age merely a wishful erasure of human producers from the picture, if not a fantasy of total automation?

Such crucial, demystifying critiques can never finally be gainsaid.

But neither, I would argue, can they finally exhaust the provocation of utopian techno-pastoral.Read credulously, four features of the mode stand out as utopian in historical retrospect, \ in so far as they would break the frame of the politics of nature that triumphed in the interim, up to and including our normative sense of political ecology.

The first feature concerns pastoral adynata and impossibilia — those “miraculous dislocations of natural law", like sheep that turn colors and trees that grow wigs, that have been hallmarks of pastoral rhetoric since Theocritus (Rosenmeyer 216). While these expressions are typically read as tropes for impossibility itself, if not signs of divine intervention, they also effect, as I suggested above, a provocative decoupling of the concept of nature from those of necessity and determination. In such figures, nature ceases to play the role of indifferent background to human suffering and triumph, or of the repetitive cycle from which the arrow of human history breaks, or of the ironclad physical determination from which we wrest our uniquely human moral freedom. Instead, other natures freely take part in the action in a manner that cannot quite be explained away as anthropomorphism.

And in so far as Golden Age pastoralists depict impossibilia as effects of political regime change, they also call into question the tenacious metaphor of nature as law (jus naturae) and the presumption that the power to suspend it is exclusively sovereign or divine.

Now that “Anthropocene” weather relentlessly historicizes the lawlike regularities of the Holocene environments we once knew, it is perhaps worth considering the behavior of terrestrial natures under the sign of their potential freedom and actual coercion, rather than their supposed necessity.

Secondly, the eco-utopian pastoral imaginary that I have traced through Darwin to Virgil and Ovid’s Golden Ages manifests an unfamiliar, indeed anti-Promethean, form of technophilia. Though present in Ovid’s self-cultivating grains, and, especially, in Virgil’s “technicolor animals,” images of the spontaneous technicity of other natures may reach their literary climax in Darwin’s The Loves of the Plants. There, Flax is cast as the “Inventress” of weaving, ably fashioning her own fibrous body into a textile; the Carline Thistle plays the “fair Mechanic” whose far-floating seeds precede the Montgolfier brothers in the “invention” of the hot air balloon, and Papyra [papyrus] is credited with introducing semiotic systems into human cultures (2:66–84, 7–66, 105–18). Darwin’s suspicious parodist reads such images of vegetable ingenuity as covert allegories for the experimentalists’ own plans to manipulate plant biology. But taken straight, Darwin’s notion of vegetable ingenuity emerges from a thoroughgoing naturalist perspective that has ceased to respect the anthropo- and androcentric distinction between the fruits of biological generation and the works of technical genius.

Situating “invention” and “representation” within the realm of generative reproduction and deviation, Darwinian techno-pastoral foregrounds the precedence and participation of other natures as coauthors in the history of art, technology, and mediation. Yet such technophilic naturalism, and this is the third point, would remain indistinguishable from familiar technologies of domination, were it not for the copresence of the pastoral insistence on leisure. Only the pause that the pastoral mode places on the workaday world and the working day ensures that the visionary technics in evidence arise not from increased human manipulation but, on the contrary, from giving space or leaving room for other beings to take up, differently, the activity of transformation to which some human societies have relentlessly subjected the other constituents of the earth.

Finally, this strange form of techno-pastoral utopianism permits a political ecology to come into view that foregrounds the authentically political axis of freedom and coercion, as opposed to the now common preoccupation with the ontological axis of “human” and/versus “nonhuman” being. It is true that an open ontology — an ontology that does not presume to dictate the capacities of various kinds of being in advance and that does not invest in the human “exception” — is propitious, if not prerequisite, for an ecological point of view. Yet it is a mistake to imagine that abolishing hierarchy among categories of being accomplishes anybody’s political liberation. In fact, where ontological leveling masquerades as political ecology achieved, it necessarily thwarts and mystifies the basic politicization of ecology.

This is because matters of justice, exploitation, and repair in the realm of ecology have never concerned the human and/versus the non-human; they have instead to do with certain humans exploiting certain other human and nonhuman beings. An analytic grounded in ontological categories of being has no means to grasp this asymmetrical and differential distribution of responsibility and harm. In this context, parables of ecological jubilee acquire their peculiar utopian, counter-ideological purchase. For, however distortedly, they begin by imagining not ontological equivalency but an end to coercion. This, I would argue, is a genuinely political gambit.

How, then, does this peculiar eco-utopian imaginary we have been tracing comport with the facts of racialization, colonization, and enslavement that enabled and fractured “the human” and his rights during Darwin’s era of their revolutionary ascendancy and counter-reaction? To explore this question, I turn, finally, to Darwin’s The Economy of Vegetation, focusing on the political ecology of slavery and abolition in that poem. Here, the human and non-human “Others of Man” welcomed into the poem’s Jacobin ecology clearly emerge as demanding and exacting allies, rather than, as I worried above, figures of wish-fulfillment or alibis for the history of technological and colonial domination. Darwin’s techniques of figuring earth and ground in The Economy, I argue, push past the interests of his own bustling, industrial bourgeois milieu to issue in distinctly illiberal, anti-humanitarian incitements to multinatural vengeance against chattel slavery and settler colonialism. In black counterpoint to our visions of “ecological jubilee,” The Economy’s parables of “ecological retribution” attempt to join forces with the many expropriated natures (human, nonhuman, dehumanized) forced into complicity by the transatlantic slave trade on the eve of a militant black Jacobinism.

Relief Poetry and the Race for/of the Ground

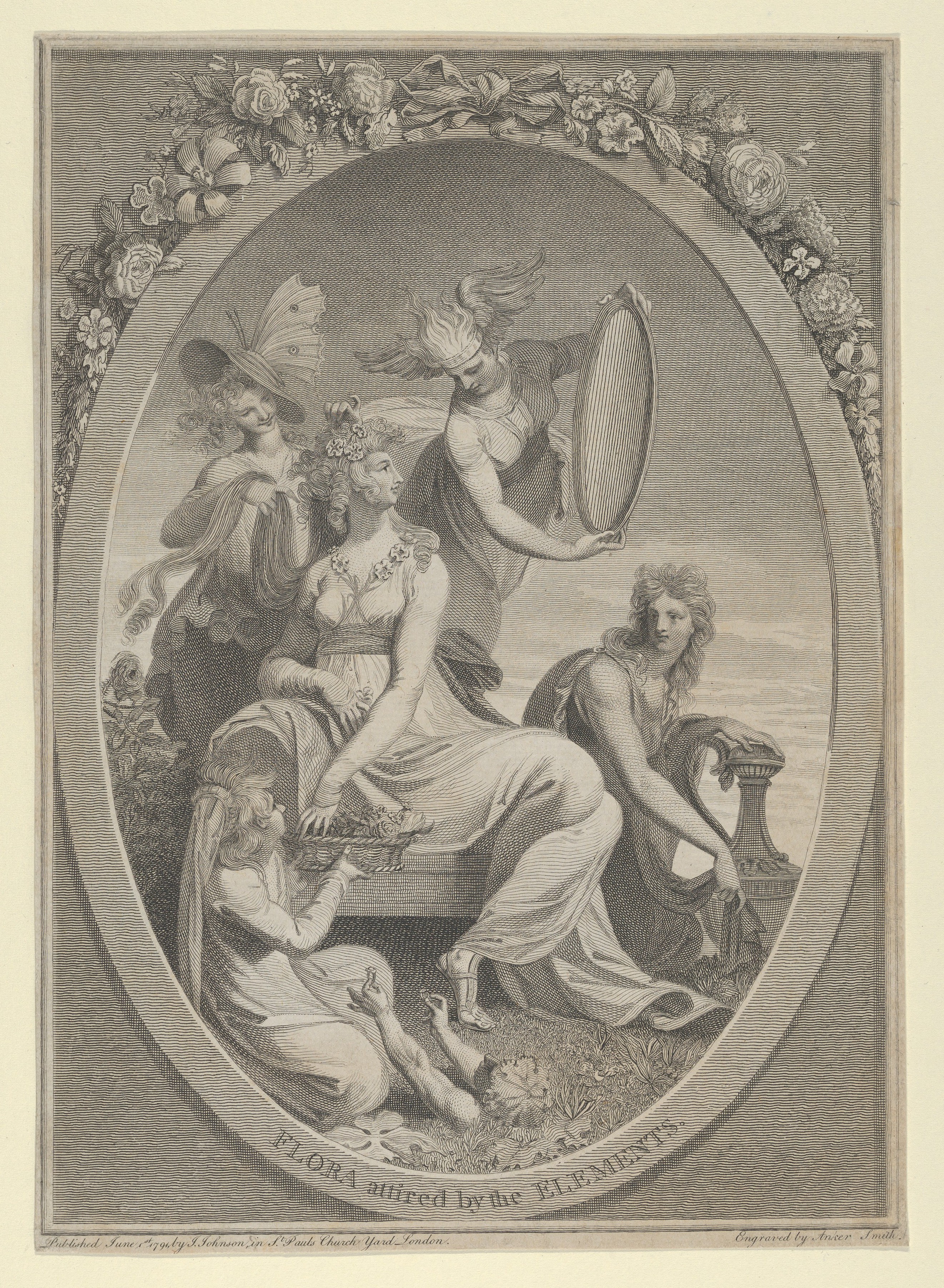

If the class politics of Darwin’s visions of communal luxury were transparent enough to make for easy parody, grasping the ecological intersection between race and class in his work requires a subtler appreciation of the poet’s figurative and compositional tactics. The brilliant Swiss-English graphic artist Henri Fuseli’s frontispiece to The Economy of Vegetation provides a perfect introduction (Figure 5). The frontispiece is supposed to represent the Goddess of Botany, “Flora, attired by the Elements,” in correspondence with the four, element-focused cantos through which the poem purports to tell the “physiology of plants.” And indeed, Fuseli’s frontispiece provides an allegorical persona for each element: Air, with her dashing butterfly hat; Fire, with a mirror to represent the action of light; Water, with an appropriate vase; and Earth offering up a sampling of her gorgeous vegetation. But who, then, is the extra, extra-earthy figure in the very bottom of the frame, reaching up from the ground, as plants do, but with brawny arms and a cap of weeds?

Figure 5. “Flora Attired by the Elements.” Frontispiece to The Economy of Vegetation, designed by Henry Fuseli and engraved by Anker Smith. Published June 1st 1791 by Joseph Johnson, St. Paul’s Churchyard. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1963.

As Fuseli intimates with this picture, supernumerary, subterranean figures like this one proliferate in the second canto of The Economy of Vegetation, the one that is devoted to the elemental activity of “earth.” Here, the actions of soils, earths, and minerals are at stake and all manner of quasi-animate beings, from slumbering seeds to incipient statues, Bastilled prisoners, oppressed Irishmen, and Africans in irons, linger in stony latency to release themselves, or be released, from the ground. As the syntax of that last sentence suggests, the distribution of agency and patience across figure and background is particularly fraught when it comes to the canto’s joint task of personifying elements of earth — that is, figuring the ground—and depicting the action of that and those who have been, in Darwin’s phrase, “disanimated” or reduced to that terrestrial matrix.

The addressees of this Earth Canto, elements of ground whom Darwin personifies as “Gnomes,” bear this figural burden: they operate as a force of frankly de-carceral natality, even as they do not quite cease to embody the inhuman, inanimate states of imprisonment and (social) death in which certain beings are interred, not to mention the stony walls, tombs, and prisons that contain them. In any case, their personification means allowing the background to surge into relief, usually at the cost of someone or something else (Canto 1, l.73). Reading Darwin’s Earth Canto alongside anticolonial ecologies of race allows us to see how the kitschy, elastic, preternatural figure of the “Gnomes” — etymologically, earth-men — come to signify the condition of imposed identification and possible allegiance between varieties of exploited ground and the racialized classes of beings conscripted to work them. Such earths and such human beings are linked by economies of extraction that Darwin cannot but trace in doing due diligence to the sites and sources of Enlightenment geological and mineralogical knowledge.

But before leaving Fuseli’s image, notice its ekphrastic function: as an engraving of a (fictional) cameo, the frontispiece offers another indispensable clue to Darwin’s mediatic art in The Economy. Critics, then and now, have agreed that Erasmus Darwin’s poetic style is highly visual, rife with allegorical personifications and written “principally to the eye,” as he put it himself, as if in proper neoclassical deference to poetry’s “sister art,” painting (ut pictura poeisis) ("Loves" 48). But the meaning of writing “to the eye” changes in light of Darwin’s understanding of the neurophysiology of sight. To address the eye with a printed word, he explains in his biomedical masterwork, Zoonomia, is to trigger cascades of associated tactile experience, literally disposing the reader’s nerves of touch to reconstitute the three-dimensional feel of the signified with her own body (Goldstein “Nerve poetry”). Darwin’s allegories of reading thus stress the kinesthetic reconstitution of poetic lines as three-dimensional forms: William Cowper attested to the effect as “Meet[ing] the eye with a boldness of projection unattainable by any hand but that of a master” (qtd. in Packham 147). Given this foundational semiotic relation between plastic plenitude and visual abstraction, it is no wonder that specimens of relief sculpture (tomb decorations, architectural ornaments, medallions, cameos, and coins) are privileged objects of Darwin’s poetic attention in the Botanic Garden.

Dramatizing the emergence of plastic forms from undifferentiated ground, objects sculpted or molded in bas-relief were ready allegories for the kind of cognitive experience Darwin hoped to produce through poetry by virtue of the physiology of reading.

As the prototype for Darwin’s poetry, the minor art of bas-relief declines to produce autonomous, free-standing forms, in favor of scenes in which form continually issues from a material ground. Likewise, Darwin’s didactic figural strategies systematically redistribute attention towards grounds and surroundings, refusing (or failing) to extricate focal agents and objects from their contextual supports and dramatizing the difficulty of selecting what to bring into relief. In addition to explaining much readerly disorientation, Darwin’s dizzying commitment to foregrounding backgrounds and magnifying the minor accounts for the most distinctive and obvious formal feature of his poems — the extensive apparatus of footnotes that supports each column of verse like a prosaic pedestal.

With a root in relevare, to lift up, but also to offer help or relief, what I term “relief poetry” captures the immediately political and sentimental pathos of a poetry saturated with the problem of what or whom to elevate, make visible, and animate by setting the reader’s living nervous system into sympathetic motion.

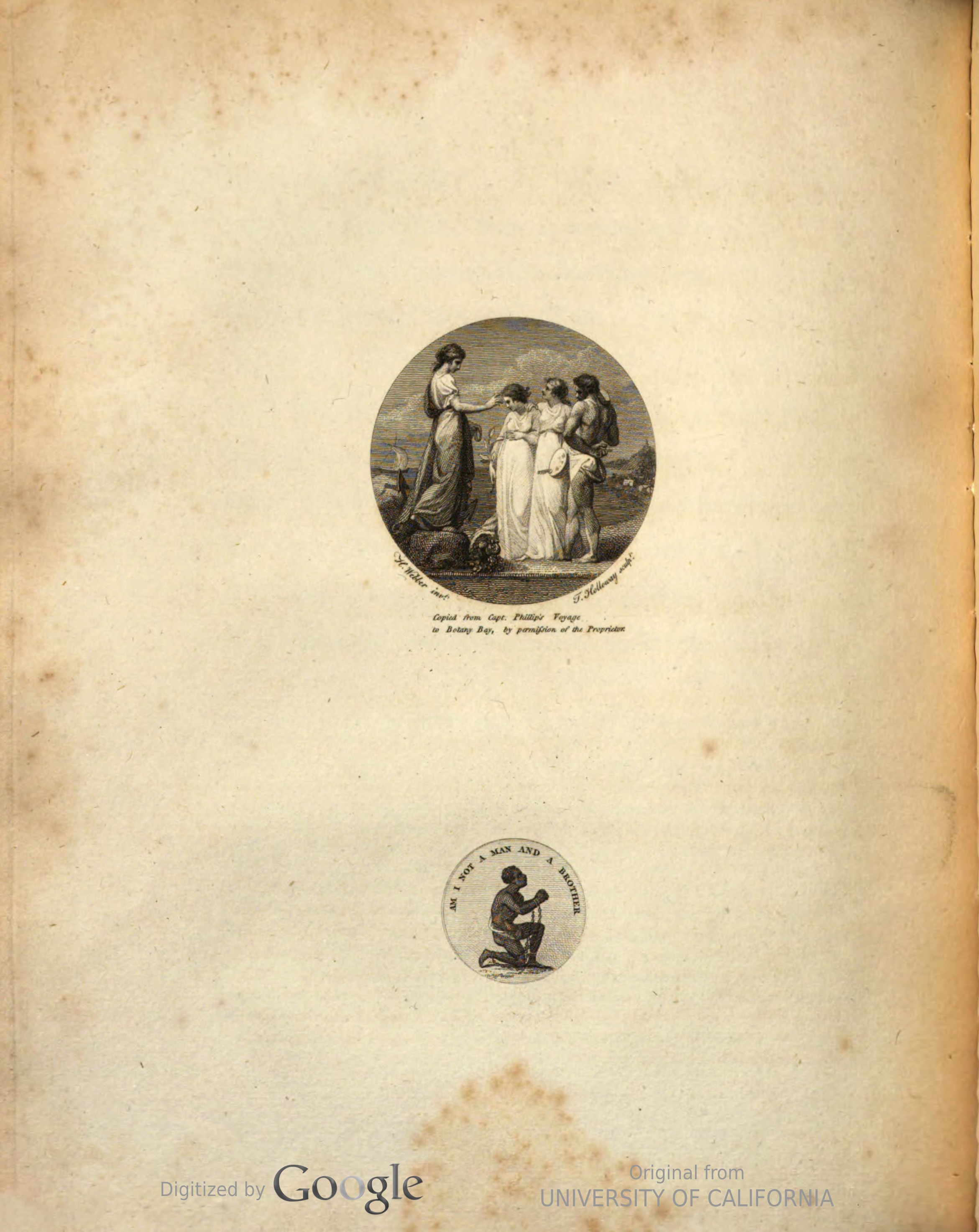

The intimate connection between relief poetics, mineral extraction, industrial manufacturing, and chattel slavery in the (Political) Economy of Vegetation comes to a head when Darwin embeds the most iconic token of the contemporary transatlantic abolitionist movement in the middle of his Earth Canto (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Illustration of the Wedgwood Anti-Slavery medallion appearing in Canto II of The Economy of Vegetation. Pictured above it is the Wedgwood cameo “Hope attended by Peace, and Art, and Labour”; see note 38, below. Courtesy of the HathiTrust.

This bas-relief medallion first appears in the course of the canto’s survey of the formation of clays and the manufacture of ceramics. Commissioned in 1787 as the seal for the London Committee of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST), the image was a smash hit in abolitionist circles, especially after Darwin’s Lunar Society friend and collaborator, the porcelain manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood, put it into mass production as a wearable cameo at his state-of-the-art factory, Etruria (Figure 7). In an irony apparently lost on those who wore it, the SEAST’s emblem against human commodification became quite the fashionable commodity: the cameo was set in snuffboxes and worn in bracelets and hairpins; like an earlier modern “meme,” it crossed the channel and the Atlantic, switching genders, settings, and media in diverse adaptations (Clarkson 191–92; Hamilton 631–52). Responding to a batch he received from Wedgwood in a 1798 letter, Lunar Society foreign correspondent Benjamin Franklin described a marked alteration in “the countenances” of those to whom he had distributed the cameo, attesting to the medallion’s particular power as a plastic relief artifact: “I have seen such marks of being affected by contemplating the figure of the supplicant (which is admirably executed) that I am persuaded it may have an effect equal to that of the best written pamphlet in procuring favour to those afflicted people” (qtd. in Hamilton 635).

Figure 7. “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” Anti-Slavery Medallion, Josiah Wedgwood & Sons, produced in Staffordshire, UK, after 1787. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Division of Cultural and Community Life.

Leading English abolitionist Thomas Clarkson credited the icon with helping to “keep up a hatred of the trade among the people” and “turning the popular feeling in our favour” during the many intervals when the Society’s parliamentary efforts were stalled (188, 191). Typifying both the propagandistic efficacy and the limits of the mainstream white abolitionist imagination — which preferred to picture a “supplicating Negro” begging kinship recognition (in the nearly unanswerable form of a negative rhetorical question) to the ongoing fact and fear of slave and Maroon uprisings in the colonies — the image also did its share of damage. In casting the enslaved person's humanity and freedom as a “gift” in the (presumptively white) spectator’s power to bestow, such visions of “the emancipation moment” symbolically steal a person’s freedom a second time by usurping their power to seize it (Wood 29).

Nor is such an analysis merely a product of hindsight. In his 1801 novel of the Haitian Revolution, The Daughter of Adoption, John Thelwall put the logic of what Marcus Wood calls “the horrible gift of freedom” in the mouth of a revered old white philanthropist in St. Domingue who surprises a radical young friend by not celebrating the news that the islands’ slaves “have thrown off the yoke” (160). “‘And is it possible, sir, after what I have heard from your lips,” the young man asks incredulously, “that you can be averse to the emancipation of your sable brethren?’” The older man replies: “I would die to emancipate them; but I cannot wish for their revolt” (160). At the core of the white Englishman’s stated, humanitarian preference for the “slow” but “certain” operation of “the sympathy of mankind,” then, Thelwall reveals a refusal to relinquish that power to emancipate the slave in which the colonist’s supremacy is staked at a value equal to that of his own life.

Darwin’s first pass at the cameo focuses on its production in Wedgwood’s factory, attempting to channel “the fair medallion’s” transmedial, transatlantic efficacy in verse, even as it draws out the occulted labor and materials behind its sentimental surface:

GNOMES! as you now dissect with hammers fineThe granite-rock, the nodul’d flint calcine;Grind with strong arm, the circling chertz betwixt,Your pure Ka-o-lins and Pe-tun-tses mixt; 300O’er each red saggars burning cave preside,5The keen-eyed Fire-Nymphs blazing by your side;And pleased on WEDGWOOD ray your partial smile,A new Etruria decks Britannia’s isle—Charm’d by your touch, the flint liquescent pours 305Through finer sieves, and falls in whiter showers;10Charm’d by your touch, the kneaded clay refines,The biscuit hardens, the enamel shines;Each nicer mould a softer feature drinks,The bold Cameo speaks, the soft Intaglio thinks. 310To call the pearly drops from Pity’s eye,15Or stay Despair’s disanimating sigh,Whether, O Friend of art! the gem you mouldRich with new taste, with ancient virtue bold;Form the poor fetter’d SLAVE on bended knee; 315From Britains sons imploring to be free . . .20

Commenting on passages such as this some thirty years ago, Maureen McNeil shrewdly observed that Darwin’s industrial poetry erased workers from the scene, instead attributing labor “to ‘gnomes’ who magically perform the work required” (17, 19). Yet equipped with mining and prospecting hammers, presiding over kilns, grinding pigments with a “strong arm,” molding and glazing forms with a “charm’d . . . touch,” these “GNOMES” certainly insinuate the working people at Wedgwood’s factory and across his far-flung supply and production chain. Rather than eliminate human producers, Darwin’s incessant apostrophes to earth-men in the plural encompass human laborers together with the materials, tools, and machines they work, conjoining both sources of occulted value that contribute to the animate “magic” of commodities. “Charm’d by your touch,” Darwin repeats, the molten metals pour, harden, refine, take shape, and shine: “The bold Cameo speaks, the soft Intaglio thinks.” What ultimately “speaks” and “thinks” through the “bold Cameo” in this passage is an industrial supply and production chain, from clay harvesting to mineral mining, chemical processing, and factory finishing. At stake is a kind of proto-Marxist prosopopoeia that makes the commodity’s power an indexical expression of the human labor and globally-sourced materials that went into its production.

Darwin’s remediation makes clear that these occulted agencies (“GNOMES”) contribute to the semiotic and affective efficacy of the cameo (its power to “speak,” “think,” and “call the pearly drops from Pity’s eye, / Or stay Despair’s disanimating sigh”). But as we will see, it is not quite clear that their meaning agrees with the milquetoast motto — Am I Not A Man and a Brother? — actually printed thereon.

On the earthen side of Darwin’s gnomic conjunction, a “new” materialist emphasis on nonhuman agency — particularly on the kind of “natural technicity” I explored in the previous section — is indeed emphatic in this section of The Economy of Vegetation. Mineral processes of taking shape and appearing, including in splendid, highly wrought forms, are literally and scientifically at stake in the Earth Canto, as in this passage on the process by which acids transmute chalk into gemstones:

Hence silvery Selenite her chrystal moulds,And soft Asbestus smooths his silky folds;His cubic forms phosphoric Fluor prints,Or rays in spheres his amethystine tints.Soft cobweb clouds transparent Onyx spreads,5And playful Agates weave their colour’d threads;Gay pictured Mochoes glow with landscape-dyes,And changeful Opals roll their lucid eyes (219–26)

In another context, to speak of stones weaving, folding, printing, and tinting their garments — to write of stones molding spheres and cubes, painting landscapes, or “roll[ing] their lucid eyes” back at the spectator — would constitute gross and indecent anthropomorphism. But such figures operate differently in a poem that systematically traces the chemical and geological production of spectacular mineral forms, revealing very real, yet very nonhuman powers to fashion the kind of shapes that humans achieve largely through artistry and technique. These mineral productions include not only rigorously geometrical forms but also mimetic similitudes of other natures: rocks and gemstones that assume the shape of wisps of hair, floral petals and spines, striated sands and tree rings, land- and seascapes. The Earth Canto also explores the mineral dimension of plant and animal vitality: Darwin traces the blush of blood-borne iron beneath a rosy human cheek and the “dark mould, white lime, and crumbling sands” that nourish and awaken dormant seeds (542). By virtue of the recently discovered chemical processes of oxidation, respiration, and photosynthesis traced in the poem, moreover, elements of earth actually effectuate animation and its signs in the poem: breath, energy, growth, motion.

Darwin’s scientific realism on the question of the relation between earthly materiality and technical artistry, between geochemistry and biological animation, means that his “GNOMES” certainly personify a sphere of suppressed identity between “earths” and “men,” bodying forth at once the action of minerals in and on human beings and of human beings in and on the earth. But as usual, summation at the level of human/nonhuman ontology will occlude the political burden of the not-quite-, not-merely-human “gnomes” in their pointed marginality and plural, collective action. Reading Darwin’s Earth Canto in its entirety in fact helps mitigate the present tendency to mistake ontology for political ecology that is writ large in those theories of the “Anthropocene” that urge the suppression of difference under the (negative) universal sign of human peril.

To repeat what ought to be obvious, at stake in the ecological predicament said to have begun in Darwin’s generation is not a question of the relation between the anthropos and the earth but of certain human societies exploiting certain other human societies and the nonhuman beings that condition their existence. And it is in the latter side of this asymmetrical relation — the human and nonhuman beings brought together as expendable resources throughout the history of New World colonization and capitalization — that the gnomic conjunction earth-men increasingly figures forth in Darwin’s poem. Such conjunctions are crucial to a political ecology capable of recognizing historical reparations as intrinsic to any project of ecological repair.

From the perspective of critical geography, Kathryn Yusoff has suggestively sketched the conjunction between (certain) earths and (certain) men at stake in the pre-history of fossil capital and “Anthropocene” geology. The “coal-black” subjects of chattel slavery and the earths subjected to fossil fuel extraction were forcibly conjoined, she argues, by “blackness” as an “inhuman categorization” that marked those who bore it as appropriable energy sources for colonial expansion and industrialization. To foreground just one literal, metabolic example of the link between England’s industrialization and its expanding colonial empire, West Indian plantation sugar and East Indian tea fueled the “wage slaves” at the base of England’s new industrial economy, those soot-blackened persons that populate both William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience and Darwin’s West Midlands region, known as the “Black Country.”

Yet Yusoff’s theory of “black inhumanist poetics,” like Monique Allewaert’s notion of “parahuman” allegiance among the beings yoked together by plantation ecology/economy, reveals not only histories of subjugation but also illicit practices of “freedom in the earth” unleashed when expropriated subjects of “inhuman categorization” tip their compulsory intimacy with the land into strategic alliance and multinatural insurgency (Yusoff xii, 15; Allewaert 7).

When Yusoff suggests that early American black inhumanist artistry can attest to “a gravitational force so extravagant, it defies gravity”, we can perceive the elective affinity between the long history of Afro-futurism and the eco-utopian “suspensions of natural law” this essay has traced by way of pastoral (100). At stake is a form of multinatural allegiance that upends not only positive laws but also the natural laws taken for their necessary ground.

Written from the contradictory heart of a dissenting, abolitionist Enlightenment centered in England’s industrializing Midlands, Darwin’s poetry ultimately manages to limn and solicit such insurgent potential within the differentially “inhuman” terrestrial collectivities that it apostrophizes without being able to activate or control. Though critics from the Anti-Jacobin forward have mocked the topical miscellany characteristic of Darwin’s poem, there is a logic to the poem’s movement in the Earth Canto, and it is frankly and increasingly - anti-colonial. In fact, Darwin traces, with subtle but intensifying condemnation, the very trajectory mapped by Yusoff’s “inhuman geography,” the geo-logic that unites the histories of fossil capital with that of colonial slavery.

Here, in brief, is that sequence of movements. From industrial-scale cameo-production in Wedgewood’s factory, Darwin next surveys the nearby fields of “sable COAL,” pointedly touching on the dark distillates of “fossil oil”: “pitchy” Naptha, and Jet, eponymously black (349, 351–52). He gives particular attention to Amber, a petroleum sublimate whose electrical properties, in Darwin’s lithic retelling, galvanize the American and French Revolutions (“man electrified man” [368]) through the person of Benjamin Franklin only to stumble on the long colonial history of the Americas and, again, the present reality of Black enslavement (353–94). In such sequencing, the volatile blackness of fossil earth forms a link between the poem’s repeated confrontations with chattel slavery in an Age of Revolution, as if the racialized conjunction between usable earth and useable people held the key to grasping the noncontradiction between the victory of the Rights of Man and an ongoing “inhuman trade.”

Darwin builds to a second engagement with Wedgwood’s medallion by castigating his countrymen as successors to the Spanish colonial profiteers who “slaughter’d half the globe”:

Whence roof’d with silver beam’d PERU, of old,And hapless MEXICO was paved with gold.Heavens! on my sight what sanguine colours blaze!Spain’s deathless shame! the crimes of modern days!When Avarice, shrouded in Religion’s robe, 415 5Sail’d to the West, and slaughter’d half the globe;While Superstition, stalking by his side,Mock’d the loud groans, and lap’d the bloody tide;For sacred truths announced her frenzied dreams,And turn’d to night the sun’s meridian beams. — 420 10Hear, oh, BRITANNIA! potent Queen of isles,On whom fair Art, and meek Religion smiles,Now AFRIC’s coasts thy craftier sons invadeWith murder, rapine, theft,—and call it Trade!— The SLAVE, in chains, on supplicating knee, 425 15Spreads his wide arms, and lifts his eyes to Thee;With hunger pale, with wounds and toil oppress’d,“ARE WE NOT BRETHREN ?” sorrow choaks the rest;— AIR! bear to heaven upon they azure floodTheir innocent cries!—EARTH! cover not their blood! 430 20

The closing anti-slavery exhortation, paraphrasing the Wedgwood cameo’s scene and motto, has the ring of a sentimental set piece: an appeal to universal brotherhood keyed to the supposed humanitarian impulse of a British readership.

But the passage also stages a limit to this fashionable, consumable form of speaking and feeling for the enslaved person. There is more to say, it seems, but “sorrow” — whether the enslaved person's or the poet’s, in his overweening sympathy — “choaks the rest.” And here the poem itself emphatically “chokes” on a kind of grievance not so easily produced and consumed: the lines sputter apart in a flurry of dashes, chiasmi, and an awkward enjambment that together shatter Darwin’s highly regular meter and end-stopped lineation. At this breaking point, the materialist nature poem capitulates into a kind of curse or prayer (the language is biblical) that radicalizes Darwin’s overall poetics of deflecting attention towards the background. Calling on the elemental milieu for relief - “AIR! bear to heaven upon thy azure flood / Their innocent cries! — EARTH! cover not their blood!”—the speaker cedes to these elemental media that quintessential artistic power of lifting something up for notice or preservation. Now the air is to bear up the slaves’ protest, the earth to ensure that their wrongly-spilled blood continues to surface. In the absence of a divine Book of Judgment, the vast material and semiotic re-combinatory that Darwin scientifically believes the globe to be is called upon to retain the evidence of the damage, to amplify the smothered voices, to enact retribution or reparation. This scene of natural justice seems to me the moral counterpart of the joyous multi-natural jubilee that tore hierarchies to the (fertile) ground.

If this were a canonical Romantic lyric poem, if it operated according to good negative aesthetic principles, it would probably stop here, at the threshold that marks the unsayable, even sublime, alterity of the Other’s suffering. But this poem is didactic, scholarly, thorough. And it is after material retribution. Having diligently followed the minerals, so to speak, through that zig-zag, transatlantic course that connects the precious metal mines of Spanish colonial Mexico and Peru (which first fueled the demand for enslaved African labor) — home to the coalfields of the English Midlands (whose incipient industrial working classes are fueled by West Indian sugar) — across the channel to revolutionary France (about to be galvanized by insurrection in Saint-Domingue), Darwin’s “GNOMES” have picked up a racialized and explicitly militant charge:

When Heaven’s dread justice smites in crimes o’ergrownThe blood-nursed Tyrant on his purple throne,GNOMES! YOUR bold forms unnumber’d arms outstretch,And urge the vengeance o’er the guilty wretch. (431–34)

And indeed, Darwin finishes out the canto by seeking evidence of what I called, at the outset “ecological retribution” — that is, he sifts through his vast natural historical archive for signs of elemental forces departing from the moral indifference usually presumed to be their law.

What emerges across the canto’s remaining episodes is a revisionist natural history in which terrestrial elements conspire with racialized subjects to reverse and avenge the progress of empire. Darwin reprises the ancient story of the Persian general Cambyses II, who attempted to “subdue Ethopia,” only to have his armies subsumed by burning sandstorms in the deserts of Northeast Africa: “wave after wave the driving desert swims, / Bursts over their heads, and inhumes the struggling limbs” (435n, 489–90; emphasis added).

In this retelling, what seems like natural disaster is fostered by the “vindictive hands” of the canto’s ever-present “Gnomes” — those half-human, half-earthen collectivities that have changed over the course of the canto from solicitous minsters of the poem’s every topical whim to militant, “resistless” agents of political violence (460, 487). Their “infuriate surge” inhumes the invaders in “one great earthy Ocean” (487, 494). Night then “bow[s] his Ethiop brow,” as if to sanctify the action, before the poem turns to celebrate the “Afric Warrior,” Hannibal, to whom the very Alps yielded passage, that he might “sh[ake] the rising empire of the world” (495, 529–41). Implicitly, over the course of this movement, Darwin has threatened that the earth will inhume that is, smother - with earth - the "inhuman trade" in which his own well-being is implicated and which gives the lie to contemporary pretenses of universal humanism and humanitarian sentimentalism alike.

Are such dark pastoral adynata, no less than the Golden, utopian ones — for in both cases, other-than-human beings suspend the laws of nature by taking a moral or political side — simply preposterous and ironic, impossibilia connoting impossibility itself? Are the twinned, utopian poles of multinatural vengeance and multinatural jubilee anything other than “bad faith” in the presumptively materialist context of Darwin’s poem — examples of the eschatology for atheists that Steven Goldsmith has detected in much new materialist thought? Or examples of unchallenging recourse to a common form of Providentialism, in which the elements are once again instruments of a just God? ("Almost Gone" 417) Maybe. Yet in the present context of global climate destabilization, it feels difficult not to read the destructive behavior of the elements as commentary on the history of human production and consumption as well as to recognize that the Holocene regularities we have known have never been as immutable as “natural law.” Moreover, and more to the point of Darwin’s groping attempts at a natural philosophy and poetics of abolition, some Black Studies scholars’ critiques of mainstream Anthropocene and new materialist theory advocate a similar form of attention to the poetic conjuncture between other-than-human beings and human subjects of dehumanization — between what is called “nature” and those “genres of being human” rendered illegible by one ethno-class’s over-representation as Man (Wynter, "Re-Enchantment" 183, 186; "Unsettling" 273, 281, 316-18, 331).

Zakiyyah Iman Jackson observes that because the racialization of some expressions of humanity as insufficiently human structures the very field of non-human being for modern Western metaphysics, attempts to move “beyond the human” without confronting race as intrinsic to the matter at hand cannot but perpetuate humanism’s historical ignorance and silence regarding Black critiques and praxes — not least those “irreverent to the normative production of ‘the human’” all along (216). It ought to go without saying that other-than-white thought and practice, early and late, has a good deal to teach Anthropocene perpetrators about comporting otherwise with other-than-human beings. Yet although the precedence and brilliance of minoritized thought on this score frequently goes unacknowledged, the inherence of racialization in the actual and theoretical territory of ecological concern for other-than-human beings is not optional: “terrestrial movement toward the nonhuman is simultaneously movement toward blackness, whether blackness is embraced or not” (Z. I. Jackson 217).

By turning so incessantly to the ground in his Economy of Vegetation, has Darwin found a way of registering the threat and promise of a kind of terrestrial justice meted out by and for subjects scarcely discernible therefrom — sustaining, and threatening his gorgeous Botanic Garden with their "inhuman," inhuming power? Not so improbably, perhaps, when the glaring fact of the “inhuman trade” revealed to anyone who cared to see that the other-than-human realm was rife with human being uncounted as such. For a natural philosopher and poet such as Erasmus Darwin, moreover, such dispossessed subjects shared space with genres of plant, animal, and mineral being whose capacity for meaning-making and historical transformation was likewise undreamt and underestimated in mainstream metaphysics.

I hope to have suggested that, issuing from deep within the culture of the perpetrators, the doggedly terrestrial movement of Erasmus Darwin’s Botanic Garden cannot but express the historical, epistemological, metabolic, and metonymic associations between the earth’s energetic darkness and that of its (literally) denigrated subjects. But more than this: the poetics draws this racialized dimension of the ground into relief, apostrophizing the human humus in such a way as to hail the retributive and reparative ingenuity of this association without enfolding it in the discourse of Man. Darwin’s awkward, impure anti-colonialism appeals not to the wrath and rapture of God but to that of the interred, those scarcely distinguishable from the ground and thereby able to partake, for better or for worse, of its more-than-human power. Who knows what other natures, in their freedom, might do, were we to cease foreclosing that possibility by force and by philosophy?