This essay examines the role of loyalist visual satire in the making and shaping of political notoriety during the period 1795-1825. Its subject is John Thelwall, the first non-elite English radical to be caricatured with reference to a recognisable physiognomy in the 1790s and, by contemporary reputation at least, the most influential and politically dangerous of the English Jacobins. It will be argued that Thelwall presented loyalist caricature with a particular set of problems. First, Thelwall enjoyed a particularly high public profile as a platform orator and lecturer in the 1790s, which meant that his face was well enough known to justify representation in more precise terms than those customarily used to depict the anonymous “Jacobin beast.” Even those that had never seen him might still recognise an accurate caricature because at least two engraved portraits and one bust on a commemorative conder coin were in circulation by the time of the 1794 Treason Trials and these likenesses share many physiognomical features in common. Second, much of Thelwall’s notoriety derived from his animated manner and volatility on the platform, which, taken together with his relatively small physical stature, offered caricaturists a vehicle for attitudinal, rather than simply facial, representation; but if Thelwall’s energetic manner was a subject for derogatory satire, it was also, conversely, the very thing that made him attractive to audiences. Third, Thelwall’s physiognomy was not remotely bestial. As contemporary biographers like John Aiken well understood, the heavy facial characteristics of a famously swarthy target like Fox, or Pitt, a man who “possessed no advantages of person or physiognomy, the first of which was ungraceful, the second repulsive” (200), were far more easily exaggerated and lampooned by caricaturists. In Thelwall’s case, the most likely effect of the sort of grotesque or sub-human representation commonly afforded in caricature to stock Jacobin figures would be personal anonymity rather than recognition, while faithful portraiture ran the equally undesirable risk of flattery. It will therefore be argued here that strategies are identifiable in the practice of James Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank by which Thelwall’s physiognomy and bodily energy were (differently) negotiated and accommodated within a broadly loyalist discourse, although neither artist found the assimilation particularly easy. Only when Thelwall announced his retirement from public life and retreated to Llyswen at the end of 1797 did caricaturists settle upon a common form of unambiguous representation and, from this moment on, Thelwall became a cartoon signifier of radical defeat and deflation.

Since most plebeian English Jacobins of the 1790s were unrecognisable to the wider public, caricature representations tended to adopt a familiar visual language. Jacobins, like Frenchmen, were invariably ragged, ignorant, unkempt, ungainly and cowardly with poor complexions, Neanderthal brows and gaping mouths. In both attitude and physiognomy, they were unprepossessing. Although the relatively respectable reformers Horne Tooke and Joseph Priestley had both been the subject of likeness caricatures prior to Thelwall’s rise to prominence in 1794, the only plebeian English Jacobin deemed worthy of personal attention between 1792 and 1793 was Tom Paine. But Paine was a writer, not an orator, and since most people had no idea what he looked like, caricaturists did not trouble themselves with his likeness. Consequently, Paine was recognisable in caricature only by his proximity to objects with which he was associated, most commonly a copy of Rights of Man, an excise book, or a pair of stays.

Besides Thelwall, the London Corresponding Society’s best known public figure in 1795 was John Gale Jones, another radical whose fame was dependent upon his oratory. But, perhaps because he was not tried for treason in 1794, Jones’s profile never appeared on commemorative tokens, and no engraved portrait is known before 1798. Consequently, when occasional reference was made to him in anti-Jacobin caricatures he was no more identifiable from his features than Paine had been.

The pseudo-science of physiognomy reached the height of its popularity in England at precisely the same time that Thelwall was honing his oratorical style and Gillray, Cruikshank and Thomas Rowlandson were fully developing the art of political caricature. Johann Caspar Lavater’s Essays on Physiognomy, originally published in German some twenty years earlier, were available to English readers in twelve versions and in five different translations during the 1790s. Lavater’s theories linking the body and the structure of the face to standards of morality and intellect were extraordinarily influential, not only among artists and their teaching academies, but among popular radicals seeking rational and scientific pathways to social and political virtue on the one hand and physiology on the other. Thelwall, who had signalled his interest in definitions of vitality by publishing a controversial essay on the subject in 1793, was an advocate and so too was Godwin. Indeed, the most popular of the 1790s editions of Lavater’s Essays was translated by the playwright Thomas Holcroft, a member of the Society for Constitutional Information and, like Thelwall, indicted and committed to Newgate for treason in 1794.

Nor did the popularisation of Lavater occur in a vacuum. A related attempt to “scientifically” measure intelligence and beauty against such material variables as head shape, nose length or the depth of the forehead was first published by the Dutchman Petrus Camper in 1791, for instance, and then translated for an edited and popular English edition in 1794. Camper’s work, moreover, was specifically concerned with the replication of these physiological ideas in the arts. Given public familiarity with both Thelwall’s physiognomy and his explosive bodily performance, caricaturists had every opportunity to adopt a more personal approach in their handling of Thelwall than they had deployed against Paine, and every encouragement to fully pursue it. As Gillray’s elderly friend, the one-time Tory MP Viscount Bateman, would later remind him, “It is in your hands to lower the opposition. Nothing mortifies them so much as being ridiculed and exposed in every window” (qtd. in Donald 170). However, although the two most prominent print satirists of the period, Gillray and Cruikshank, both made use of physiognomical likeness in dealing with Thelwall, they addressed the problem of his physical energy in diverging ways.

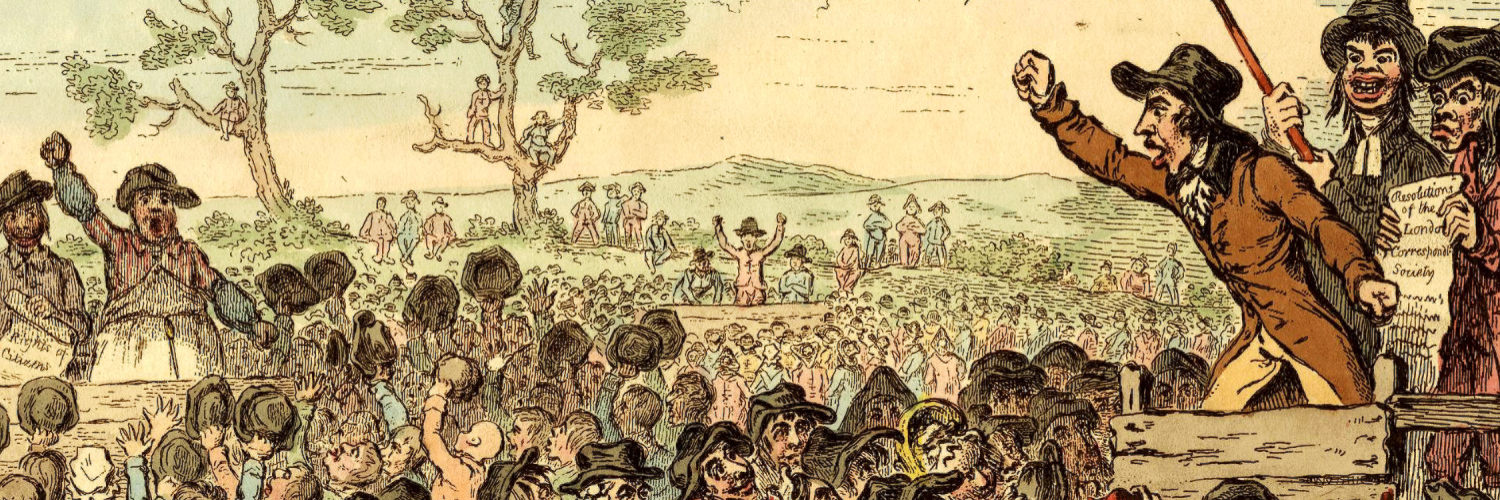

Fig. 1 James Gillray, Copenhagen House (1795). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1851,0901.759].

Thelwall’s first appearance in caricature is also his best known. Gillray’s Copenhagen House (1795) depicts the mass outdoor LCS meeting of 12 November 1795 and was published four days after it. Thelwall is not named in the print, nor is he identified from speech bubbles or rolls of paper with “lectures” written on them, as he would sometimes be in later efforts. But he is clearly identifiable from his physiognomy and from what we might term his oratorical attitude. Gillray, who had studied physiognomy in the Royal Academy schools, was, like any trained artist of the period, well acquainted with the contents of Lavater’s Essays, and in 1798 would make direct reference to them in a satire entitled Dublures of Characters or Striking Resemblances of Physiognomy, in which members of the Foxite Opposition were made to reveal a series of satanic alter-egos. The association made by Gillray between face, expression and body in his depiction of Thelwall for Copenhagen House closely echoed Lavater’s assertion that “the affections of the mind should express themselves by the voice, the gestures, but especially by the countenance, and man should thus communicate to man his love, his resentment and the other emotions of his soul by a language perfectly infallible and universally understood” (Lavater 51). Thelwall understood platform performance in these cohesive terms too, for as he saw it, it is “uniformity and animation which should give life to [these] lectures” (Tribune 3: 137). Only a month before the Copenhagen House meeting, he had apologised to an audience when poor health inherited from prison forced him, “a shattered feeble remnant of a man” (3:137), to deliver lectures reduced to “a statement of facts and principles and the conclusions that result from them,” rather than “enter into digressions that would arouse my passions and feelings and occasion me to speak with particular warmth and animation” (3: 17). Without the uniform engagement of heart and body with mind and voice, he feared, a lecture lost its capacity to inspire. This uniform engagement is deeply embedded in Gillray’s representation of Thelwall, accentuated by a profound separation from both the collective grotesquerie of his dullard audience and the more prosaic attitudes of the less accomplished orators on the other two platforms. While the lowly status of his platform colleagues is indicated by their shabby clothing and trades (butcher, dissenting minister and barber), Thelwall appears dressed as a gentleman of sorts, elevated materially and figuratively from the LCS and its audience, in a greatcoat and a ruffled stock.

Fig. 2 Isaac Cruikshank, Cool Arguments!!! (1794). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1851,0901.759].

If we are invited to read a degree of irrational anger in the clenching of his fists, and uncouthness in the gaping of his mouth, it remains a considerably kinder portrayal than the oddly twisted form given to Thomas Erskine, Thelwall’s principal defender a year earlier during the Treason Trials, by Isaac Cruikshank in Cool Arguments!!! (1794). Gillray’s Thelwall retains a degree of balance and self-possession that Cruikshank’s Erskine has almost lost, the barrister’s awkward body satirically betraying the “cool argument” of the title, and rendering him in the process considerably more comic than the bête noir of Jacobinism. Thelwall was no stranger to the political dynamics of empiricism and distortion in the manufacture of “likeness,” or the delicate balance between truth, poetic licence and caricature, and wrote about it at some length. In the course of his pedestrian tour from London to the West Country to visit Coleridge in 1797, he studied the classical busts at Wilton House and noted discrepancies between the recorded features of various Roman heroes and villains and their historical reputations. He was fascinated by the conflicting messages suggested by Seneca’s “open mouth and the mixture of voluptuousness and intellectual power blended in the lines and solid parts of the face” because he regarded Seneca as a genius too flawed “to live with the purity of a philosopher.” But two busts of Brutus, whose love of liberty and virtue Shakespeare and a great many historians had been so careful to record, presented a physiognomy that was “assassination personified.” Here was cause for thought. “What shall we say to this? Are the portraits fictitious? Or have we been imposed upon by legendary panegyrics?” The latter, he decided, was the more likely answer. The politically motivated distortions of history might always be exposed by returning to the evidence of the face itself. “Perhaps our admiration of Brutus or Cassius may have been carried too far,” he reflected. “For my own part, establish the authenticity of the likeness and I will believe the testimony of a man’s countenance in preference to his historian” (“Pedestrian” 30-32).

Fig. 3 Henry Richter, John Thelwall (1794). Photo by S. Poole.

Fig. 4 William Ridley (after Henry Richter), John Thelwall (1794).

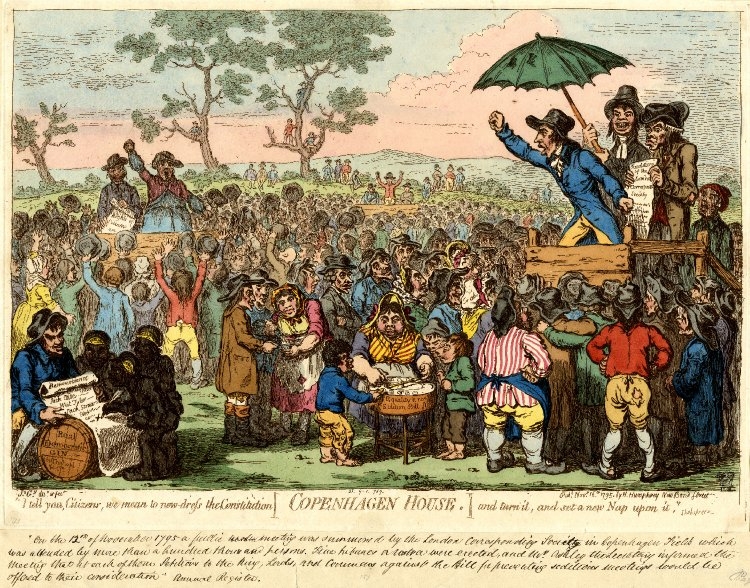

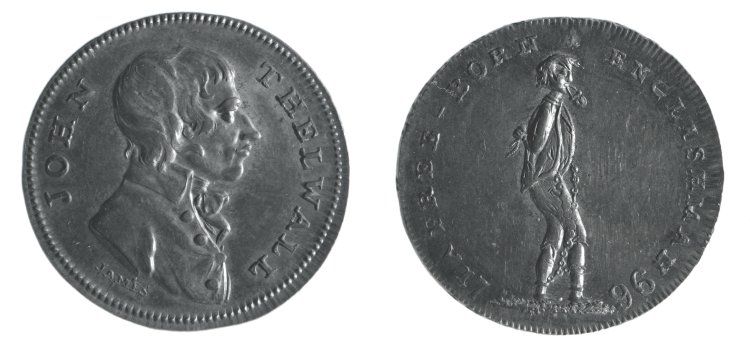

By the time of the Copenhagen House meeting, Gillray had at least two serious portraits of Thelwall upon which to draw, both derived from sketches taken in the Tower by Henry Richter, the brother of Thelwall’s co-defendant, John. These two engravings are equally careful in their recording of Thelwall’s slim body, long nose, strong chin, slight pinching of the brow (both this and the rolled scroll recalling classical representations of Demosthenes), thin, fashionably cropped hair cut back from the forehead but just over the ears, and an elaborately ruffled stock. It is fair to assume that this is a close enough approximation to Thelwall’s actual appearance at the age of thirty, and as portraits they correspond quite convincingly with the sharp featured bust of Thelwall that appeared on commemorative conder tokens at roughly the same time.

Fig. 5 Conder token with head of John Thelwall (1796). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum # SSB,237.70].

Fig. 6 William Hazlitt (attributed), Portrait of John Thelwall (c. 1800-05). © National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig. 7 Anon., Head of John Thelwall from Public Characters, 1800-1801. Photo by S. Poole, from a copy of Public Characters in the Library at Downside Abbey, Somerset.

To these we can add John Hazlitt’s portrait in oils, and the miniature profile line drawing that accompanied his appearance in Public Characters, both made about six years later when Thelwall had “retired” from politics. These various portraits may be read as self-conscious attempts to emphasise physical signs, not of oratorical enthusiasm or of reason lost but of reason secured. They emphasise the performative element of Thelwall’s public persona as transitory and self-controlled, and provide a balance both to the appearance of spasmodic excitability on the platform and to some of the crude representations of the diseased and emaciated Jacobin body so characteristic of the visual language of loyalism.

Although Gillray made no attempt in this print to miniaturise his subject, Thelwall was the first to admit his own “want of figure” and “feeble constitution” (“Prefatory” 64), for as we learn from his second wife, Cecil, “his chest was narrow; part of his pleura had firmly adhered to his ribs” (Mrs. Thelwall 40). Thomas Noon Talfourd regarded Thelwall as “small” and “compact” (298), and the Bow Street Officer James Walsh concurred; he was “a little stout man with dark cropt hair,” quite unlike the dominant figure in Copenhagen House. This smallness of stature did not make him appear feeble, however, for he was strongly built and held himself well. Talfourd, in fact, also remembered Thelwall as “muscular,” with a body sturdy enough to support “a head denoting indomitable resolution, and features deeply furrowed by the ardent workings of the mind” (298).

The perception of balance between passion and reason was of particular concern for public speakers like Thelwall for, as Godwin would have it, every orator was prone to “a due mixture of spices and seasoning” in his delivery, since “quiet disquisition and mere speculative enquiry will not answer his purpose” (20). Bombastic enthusiasm, Godwin feared, led to exaggeration and over-emphasis and risked a counter-productive incitement to irrational acts of violence. It is well known that Thelwall challenged Godwin over these allegations during the public debates over Pitt’s Gagging Bills in 1795, and it is clear that Godwin felt his case proven by the intemperate nature of Thelwall’s rebuttals, and the “angry temper” that gave rise to them. “It is impossible for me to answer the farrago of abusive language you send me,” Godwin retorted (Cestre 203-04). Godwin was not alone among Thelwall’s political sympathisers in airing his misgivings about the orator’s volcanic temper. Talfourd put it this way: “Thelwall spoke boldly and vehemently at a time when indignation was thought to be a virtue . . . . [S]peech was, in him, all in all, his delight, his profession, his triumph, with little else than passion to inspire or colour it” (296). More than once Thelwall intimated that the passions of the heart should not be held accountable to the reasonings of the head, but rather the two should be Socratically harmonized, though few thought he had achieved it. An inevitable consequence of oratorical passion, it was argued in one anti-Jacobin tract, was that “the multitude echo the variable will of the demagogue, he wields their dreadful caprice and hurls it at whatever opposes his own interests. The multitude is the unenlightened part of a Nation; and the multitude is the tool of the demagogue” (Rights of Citizens 116).

If the representation of Thelwall’s features in Richter and Hazlitt’s portraits was intended to invoke a calm and intellectual counterpoint to platform energy, it was nevertheless subject to alternative readings by loyalist writers who saw in it less a revelation of the self than a concealment. The anti-Jacobin novelist George Walker, for example, who used Thelwall undisguisedly as a model for his sinister and classically minded democratic orator in The Vagabond (1799), considered these same features to reveal “a little dark-complexioned man with a most hypocritical countenance and a grin of self-applause mingled with contempt” (79).

Physiognomical interpretation was, unsurprisingly, of considerable interest to Thelwall, who confirmed his belief in Lavater’s strictures on more than one occasion, and took more than a passing interest in the facial and cranial peculiarities of his own family. To Peter Crompton of Liverpool he assessed his son Algernon in 1798: “I have a thousand Shandean notions about him—the peculiar form of his head, the remarkable cast of his features, and the thousand antic forms into which he is every now and then distorting them fill me with many a proud and many an anxious thought.” In fact, Thelwall was confident enough of his own features to seek comment from Coleridge on a now lost self-portrait, either written or drawn in 1796, and the satisfaction with which he regarded the strong lines of his own nose and chin may be judged from the rude remarks he would later make about the supposed weaknesses of his literary adversary Francis Jeffrey’s.

Since Jacobin self-representation was partly to be a balancing act between base demagoguery and Demosthenian assertion, Thelwall was careful to embrace and improve upon Lavater’s unification of voice, gesture and countenance in the construction of his own public self as well as in the advice he later gave to his elocution students. There was an important distinction to be made between histrionic excess or the “theatrical elocution” of the stage, and the sort of expressive oratory that arose from “the harmony of features, voice and action.” Controlled gesticulation, moreover, was natural to the “deportment of all persons when excited,” a “natural part of eloquence” in fact, and its “habitual restraint the chief cause of graceless and extravagant action” (Selections-York 2). Thelwall’s students were lectured on physiognomy and encouraged to cultivate facial expression as a natural accompaniment to vocal inflection and bodily stance. The “fashionable insipidity” of an “inexpressive countenance,” Thelwall told them, suggested only a “vacancy of mind” (Selections-Hull). Moreover, insipid oratory was the consequence of a conspiracy amongst modern elocutionists “to reduce almost all public speaking but that of the stage to one sympathetic monotony of tone and look and attitude” so that “all expression of attitude and feature . . . ought to be confined to the mummeries for which they are supposed to have been invented” (Vestibule 20).

A holistic approach to vitality and character is a constant trait in Thelwall’s writing. From our introduction to his imaginary companion and virtual alter-ego, Ambulator, in The Peripatetic of 1793, with his “small, but erect and manly form, his open brow, his strong but softened features, and his forward-darting eye, which reveal to the physiognomist the internal graces and dignity of his mind” (88-89), to the manifesto-like appeals of the Vestibule of Eloquence seventeen years later, Thelwall consistently linked the science of physiognomy with improving elocution, deportment and intellect. Language alone would not suffice; on the contrary, “nature’s epitome, like nature’s self, must sympathise through every element: motion and look and attitude must manifest the inspiration of genuine feeling; and every portion of the frame must be vital with expressive eloquence” (Vestibule 21). Gillray, whose own practice was largely based upon an appreciation of exaggerated animation and physiognomical distortion, was clearly fascinated by Thelwall and his attitude towards him remained characteristically ambiguous. In Copenhagen House, the dynamic contrast between Gillray’s Thelwall and Gillray’s crowd is not intended to confer much credit upon the latter; indeed, the argument of the print is dependent upon the accentuation of distance between the two. Understandably, Thelwall rejected any association between his crowd and Burke’s swinish multitude, and used physiognomy once again to refute the charge. “I am not speaking to an unenlightened and uninformed auditory,” he declared, “I can perceive countenances, many of which I know, and in many of which, though I do not know them, I can read the lines of intelligence and education” (Tribune 3: 248). Gillray may not have been prepared to accept that but, like Coleridge, he was not unaware that “Thelwall is the voice of tens of thousands” (Coleridge, Plot 20-21), and the clear evidence of Thelwall’s personal magnetism did not present obvious strategies for hostile loyalist caricature.

Thelwall certainly felt his own persuasive genius, “for he had the satisfaction of seeing persons filling considerable stations in society who had at first gone to hear him with every hostile intention, become his warmest approvers; and very frequently, in after life, he was greeted by men of first-rate intellect and staunch reformers, with their acknowledgement that he was their political father” (Mrs. Thelwall 405-06).

Fig. 8 Anon., Billy’s Hobby Horse (1795). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1876,1014.30].

Fig. 9 Isaac Cruikshank, The Royal Extinguisher (1795). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1868,0808.6487].

The exceptionalism implicit in Gillray’s image can be demonstrated by comparing it to the only previous attempt by a caricaturist to represent LCS oratory, the anonymous Billy’s Hobby Horse (1795) in which the St. George’s Fields meeting of 29 June 1795 forms part of the background. The only speaker that day was John Gale Jones, visible in the print with his arm raised, but no attempt has been made at likeness or oratorical posture and the meeting’s marginal position behind the principal figures of Pitt and John Bull reduces its role to one of commentary and context rather than argument and agency. We might also note the immediate and wholesale plagiarism of Gillray’s figure by Cruikshank in The Royal Extinguisher (1795), published a few days after Copenhagen House, and avoiding the political ambiguity underpinning Gillray’s print. In Cruikshank’s hands, Thelwall, though bodily identical, has become ridiculously Lilliputian; railing punily against Pitt’s towering Gulliver while the shelter of Gillray’s sun umbrella has been replaced by a gigantic candle snuffer. By contrast, Gillray’s ambivalent refusal to treat the LCS as a serious threat was not particularly helpful to ministerial arguments for the suppression of free speech and public assembly in the wake of the attack on the King’s coach a few weeks earlier. Indeed, some of the most diminutive and ineffectual figures in Copenhagen House are the central representations of Fox and Pitt as children chancing their luck on an EO table while an unrestrained Thelwall thunders above their heads. Perhaps to avoid the ambiguity of presenting the public with the sort of irrepressibly energetic Thelwall they might actually recognise, therefore, Cruikshank changed tack after the passage of the Two Acts, divorced the orator from his popular constituency and re-fashioned him as a dupe of the Foxite Whigs.

Rumours of a closer working relationship between the Fox and the LCS began to circulate publicly late in 1795. Cruikshank had already placed Fox, Sheridan and Stanhope in the Lilliputian crowd surrounding Thelwall in the Royal Extinguisher, and Gillray had made them leaders of the mob that attacked the King’s coach on October 29th in his highly ambiguous Republican Attack. These rumours gathered pace, however, after Fox and several of his parliamentary allies attended Thelwall’s speech against the Gagging Bills at the last mass outdoor meeting of the Society on 7 December (Morning Post 8 Dec. 1795). This was followed by a series of debates on “the most probable means left of saving the country from the despotism of the minister” in the Westminster Forum at which John Gale Jones claimed he had been waited upon by prominent Whigs and invited to join a general coalition against Pitt (Thale 330). In fact, according to Cecil Thelwall’s account, “Thelwall was the means of this union which now took place between the Whig Club and the London Corresponding Society,” for each had become “necessary to the preservation of the other,” although the LCS officially denied having anything to do with it (Mrs. Thelwall 399). Rumours circulated during the general election campaign of 1796 that Thelwall was intending to contest war minister William Windham’s seat at Norwich, but in fact he busied himself in supporting Fox at Westminster, where the Whig leader and the Pittite Admiral Allan Gardner were involved in a three-cornered contest with Thelwall’s first political mentor, John Horne Tooke. Thelwall had quarrelled with Tooke after the Treason Trials, but hoped now to see him elected with Fox at Gardner’s expense. He used the campaign to make a number of speeches calling for cross-party radical unity to defeat the ministry, but although Fox was returned, Gardner forced Tooke into third place.

Despite appearances, Tooke and Fox had not in fact entered into a coalition, but government supporters made capital from it and were quick to point out that, “among the worthy electors in the interest of our senator were to be numbered Citizen John Thelwall, Citizen John Gale Jones, and not a few members of the Corresponding Society” (Bisset 3: 381). This too was the theme of Thomas Rowlandson’s Sir Alan Gardiner at Covent Garden (1796) in which, not for the last time, Thelwall’s unwise associations left him headless, along with both Hardy and Tooke. This was the first caricature print to use the verbal joke “tell-well,” a nick-name for the lecturer that first surfaced in The Times in 1794.

Fig. 10 Thomas Rowlandson, Sir Alan Gardiner at Covent Garden (1796). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1935,0522.4.70].

Shortly after this, Thelwall left London for his first provincial lecture tour and ceased for a time to be of interest to the capital’s satirists. However, when Fox found himself as without influence in the reconstituted parliament as he had been in the previous one, he led his party into a symbolic secession from the House, citing as causes Pitt’s retreat into cabinet government and the intransigence of the ministry over reform and the continuation of the war. Instead, he proposed co-operation with the extra-parliamentary reform movement who would otherwise be either “too weak to resist the Court” or, more ominously, prone to dangerous “excesses” (Public Advertiser 8 Aug. 1797). Unsurprisingly, Fox’s loyalist critics suspected darker motives, for “telling the People that their parliament will not listen to reason” was “little short of an invitation to civil war” (Wells 65-66). The suspicion that radicals like Thelwall and Tooke were secretly plotting with disaffected parliamentarians like Fox, Stanhope, Sheridan and the Duke of Bedford to overthrow the State proved irresistible to satirists and in June, Thelwall reappeared as a pivotal figure in a series of critical prints by Cruikshank.

Fig. 11 Isaac Cruikshank, The Diversions of Purley (5 June 1797). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1868,0808.6637].

Fig. 12 Isaac Cruikshank, Delegates in Council (9 June 1797). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1868,0808.6641].

These prints do not address Thelwall’s bodily energy, however, partly perhaps because other ministerial propagandists were emphasising the success of the Gagging Acts in stopping his mouth. “It is all over with me,” he is made to lament in one pamphlet,

Where shall I sedition roarIn what room my tribune placeThelwall’s business is no moreStopp’d for ever is his race. (Decline 17-18)

For Cruikshank, however, Thelwall was more dangerous without his lectern than with it. In these prints, he may be recognised from his likeness and from textual allusions to lecturing, but he is otherwise unremarkable as he consorts privately with his influential new allies. In the first of them, The Diversions of Purley, Thelwall appears as part of the secessionist coalition with Erskine, Fox, Sheridan, Stanhope and Grey. He is no longer the orator but the secretive plotter, in a busy nursery, scissoring “old fashioned” aristocratic ermine to make swaddling for Fox’s monstrous offspring, master Revolution and miss Sedition. Should his profile be insufficient to identify him, he addresses a figure who breaks into the frame from the left with a query, “Did you hear my last lecture?” This figure is Horne Tooke, whose best known work provides the satire with its title, and who answers Thelwall with another question, “Have you heard from Sheerness”? Together, Tooke’s question and his peripheral position provide a commentary on Thelwall’s role as intermediary between Fox and Tooke on the one hand and between Jacobinism and the naval mutinies on the other. The mutiny at the Nore, close to the Kent coast at Sheerness, had broken out simultaneously with the second mutiny at Spithead, Portsmouth. John Gale Jones had been sent on a lecturing mission to the Kentish dockyards in 1796 and the LCS had gone to some trouble to encourage radical societies at Portsmouth. They were now widely suspected in the loyalist press of agitating amongst the sailors and schooling them in political and democratic demands. In May, The True Briton had claimed Thelwall was on the Isle of Wight, “not an indifferent spectator, doubtless, of the late proceedings at Spithead,” and Cruikshank’s allusion is not unpredictable (12 May 1797). Diversions of Purley was followed four days later by a second comment on the mutinies, The Delegates in Council. Thelwall, having flitted from his Janus-like role between Fox and Tooke to the lower deck HMS Sandwich at the Nore, was now placed in a more sinister position as familiar, prompter and grog-server to the mutineers in the negotiation of terms with Admiral Buckner. Tooke resumes his rightful position under the table with the Foxite parliamentarians, but Thelwall stands openly beside his grotesquely drawn plebeian associates, fixes the Admiral squarely in the eye and issues instructions: “Tell him we intend to be masters,” he says, “I”ll read him a lecture.” Here, Cruikshank persuades his audience, was a man uniquely comfortable in both Opposition and insurrectionary circles and apparently able not only to move between them with ease but to direct operations from an assumed position of authority.

Fig. 13 Isaac Cruikshank, Watchman of the State (20 June 1797). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1868,0808.6644].

Later in the month, Cruikshank produced a third related image, The Watchman of the State. As in Diversions of Purley, Fox is the central figure, this time in the character of an absconding watchman, deserting his post and abdicating his responsibility to keep the more extreme wing of the democratic coalition under control. Lauderdale and Bedford watch and applaud while Horne Tooke, Sheridan, and Stanhope lay gunpowder trails to destroy the constitution, the Commons and the Lords. A diminutive Thelwall, with a paper marked “Norwich lectures” in his pocket, once again provides the link with extra-parliamentary mischief making, this time lighting a taper from Stanhope’s lantern in a bid to destroy aristocracy.

In all three of these prints, Cruikshank’s approach is different from Gillray’s. Thelwall’s physiognomy is reproduced with sufficient accuracy to make him recognisable, and his features do not undergo even the slight comedic distortions made use of by Gillray. But no allusion is made to his oratorical voice or to his bodily energy. He is in fact quite unremarkable, and this, perhaps, is Cruikshank’s point. What makes Thelwall dangerous is not the bluster and posturing of his high profile public performances but his chameleon-like ability to flit between various reform parties, belonging to none but at ease in any. Given Thelwall’s self-evident personal attractions and his polymathical intellectual dabblings in science, philosophy and the arts, some loyalist approaches to Jacobinism identified a framework of fluidity, sophistry and adaptability in the belly of the beast. As the arch-loyalist Robert Bisset put it, seemingly with Thelwall in mind: ‘One prominent feature often mentioned in Jacobinism is its versatility . . . . He is at one time a pamphleteer . . . we have him next as a novel-monger . . . next the Jacobin tries his hand at play-writing . . . the Jacobin now changes himself into the form of a lecturer, and from his tub his nightly nonsense pours . . . dabbling a little in metaphysics which are too deep for being fathomed by his line of understanding, he next comes upon us as a political philosopher . . . he turns critic next, and as a reviewer attempts to spread the beneficial doctrines and precepts of the various works he brings out in his other manifold capacities . . . he is a Socinian, a Methodist, a Seceder, a Presbyterian, a Roman Catholic, or a Mahometan; he has projected to be a Hindoo; he has been seen in the mosque and on his way to the pagoda, he struts at the school desk, he pops upon us in the conventicle, and assails us on the roadside. (Bisset 2: 242-43)’ Duplicity of this kind is rarely betrayed by low appearance or bad physiognomy; on the contrary, when understood on these terms, the Jacobin may be anonymous, prosaic, unnoticed. The Jacobin was not the first folk-devil to be constructed in this way for it had also been the fate of the eighteenth-century sodomite, another sinister figure variously imagined to be recognisable from his posture, speech and clothing, or alternatively concealed by outward shows of the ordinary. Sodomites did not always conform to the popular stereotype, lamented the pamphleteer Emanuel Collins in 1756; on the contrary, their insidious posturing as something they were not made them doubly dangerous. They “fly generally to large cities to hide themselves in the multitude, and seek security in the crowd . . . . Undaunted and upright they crowd our publick walks, unaw’d by guilt, and unappal’d by the fears of any impeachment” (1, 7). Like Jacobins, they were masters of facade and pretence, “lurking,” as one newspaper put it in an attempt to forewarn its readers, “under the different characters and disguises of a solicitor, a gentleman of an estate, a steward to a nobleman, a cook, a tapster, and other shapes” (Newcastle Courant 24 Sept. 1737).

Fig. 14 James Gillray, Promis’d Horrors of a French Invasion (1796). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1851,0901.823].

The contrast between Cruikshank and Gillray’s practice at this time was further demonstrated in the latter’s complex and highly finished Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion – or – Forcible reasons for Negotiating a Regicide Peace (1796). In this print, Gillray’s captivation by Thelwall’s energy and his ambivalence towards him is clear once again. Small in body but active and highly spirited, a recognisably sharp-featured Thelwall takes the Great Bedfordshire Ox (his opposition ally, the Duke of Bedford) by the tail and, with a well-aimed kick and a wave from a rolled copy of his lectures, encourages him to up-end a flailing Edmund Burke at the doorway of Brookes’s club in St James. Like Cruikshank, Gillray uses Thelwall more as an abettor and instigator than a direct agent, but he is possessed by a comic joie de vivre that scarcely suggests the “promis’d horrors” of the design. The loyalist message of the print is compromised in any case by Gillray’s insistence on using dice, playing cards and an EO table in White’s Club to cloud our sympathies for the misfortunes of a dissolute Royal Family (the Prince of Wales and the Dukes of Clarence and York).

Fig. 15 James Gillray, End of the Irish Invasion (Jan. 1797). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1868,0808.6585].

Gillray was not uninterested in the Corresponding Society’s relationship with the seceding Foxites, but unlike Cruikshank, he used the unlikely coalition as a vehicle for light comedy, doomed to failure, and ultimately the cause of Thelwall’s undoing. He is never a threatening figure in Gillray’s work; rather, he is transformed from a fountain of energy in 1795-96, to the representation of Jacobin defeat by the beginning of 1797. InThe End of the Irish Invasion (1797), a comment on the dispersal of Hoche’s invasion fleet off the coast of Ireland in 1796, French complicity with the Foxite/Jacobin coalition founders in storm-tossed seas and Thelwall is figuratively shipwrecked alongside Erskine and the Whig secceders. With his lectures in his pocket, and a pack of playing cards bobbing on the water behind him, Thelwall’s political “gamble” has failed and he is, quite literally, out of luck and out of his depth. A few days later in another Gillray satire, The Tree of Liberty must be Planted Immediately (1797),

Fig. 16 James Gillray, The Tree of Liberty Must Be Planted Immediately (Feb. 1797). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1868,0808.6594].

Thelwall is once again a victim of hubris. Having failed to learn the lessons of his own lectures on classical history, his severed head lies slightly to the side of those of the Whigs, meaningfully separated from them by the executioner’s axe and resting upon a signifier of his own folly, a notice announcing “lectures upon the fall of the republic.” It is true that Gillray featured a revitalised Thelwall the following year in The New Morality (1798),

Fig. 17 James Gillray, The New Morality (1798). Photograph by S. Poole, image reproduction for non-commercial purposes, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

but this was a directed commission for the Anti-Jacobin magazine and prompted as much by a specific reference in Canning’s accompanying verse as any decision of his own. The revitalisation is in any case compromised once again by defeat, robbing Thelwall of power and influence despite his deportment. As assorted English Jacobins pay homage to Larevelliere Lepaux—the “High Priest,” as Canning put it, of the French cult of “Theophilanthropy”—Thelwall, portrayed as a railing imp on Bedford’s Leviathan shoulders, has become more feeble-bodied than before. In severely mud-spattered clothing, Thelwall is clearly no longer the “voice of thousands” and there is now an absurdity to his animation. The mud is an allusion to Thelwall’s hostile reception from loyalist mobs during recent provincial lecturing engagements at Derby, Norwich, Stockport and Ashby de la Zouch, and referred to in Canning’s verse: “Thelwall and ye that lecture as ye go, / And for your pains get pelted, praise Le Paux . . . .” By the time of this print’s appearance, Thelwall had in any case ceased to pose any significant threat because he had publicly announced his retirement to Llyswen, Wales, at the end of 1797.

Fig. 18 Thomas Rowlandson, A Charm for a Democracy (1799). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1851,0901.958].

The Anti-Jacobin’s prime target in 1798-99 was not the individual influence of the charismatic lecturer in any case, but Opposition newspapers and essayists. Apart from the usual Whig suspects, Thelwall’s companions in the New Morality’s procession of villains include Godwin, Coleridge, Southey, Holcroft, and Priestley besides representations of the Morning Chronicle, the Courier, the Star and the Morning Post. In A Charm for a Democracy (1799), produced by Thomas Rowlandson for the Anti-Jacobin Review, another motley procession of radicals presides over a seditious cauldron heated by a bonfire of Jacobin texts, including Thelwall’s Rights of Nature, to a fare blown by a newsboy from the Courier. But this is a print that celebrates radical defeat; it is anything but alarmist. Thelwall stands in line, prematurely aged, his lectures tucked under one arm but effectively silenced. “I’m off to Monmouthshire,” he says. In loyalist discourse, the withdrawal of voice left Thelwall an empty windbag, his vitality extinguished, his lectures ineffective when committed to print. The Anti-Jacobin was in buoyant mood:

Tied up, alas! Is every tongue,On which conviction nightly hung,And Thelwall looks, though yet but young,A spectre. (“The Jacobin” 135)

Fig. 19 Samuel de Wilde, School of Eloquence and Grace (1808). Photograph by S. Poole, image reproduction for non-commercial purposes, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

As Llyswen recluse and then professional elocutionist over the subsequent twenty years, Thelwall received little attention from satirists. When he did, it was only to suggest confluence between respectable cover and Jacobin intent, and only because the next generation of Whigs after Fox’s death were finding it no easier to exert lasting political influence. In The School of Eloquence and Grace (1808), a complex engraving for the Satirist, a large party of washed up Whig parliamentarians, defeated in the election of 1807, have booked themselves into Thelwall’s Bedford Square Institute to have their inarticulacy and other ineptitudes examined. Thelwall opened the Institute in 1806 to “pupils who have impediments of utterance, of whatever description . . . who may either labour under the like imperfections or be desirous of improvement in the accomplishments of reading and recitation, conversational fluency, public oratory, and the principles of criticism and composition,” and in a later prospectus he made specific overtures to parliamentarians who, “may depend upon every attention that can be instrumental either to the improvement of their oratorical powers or the direction of their studies” (qtd. in Duchan 139).

Given an Opposition that still included erstwhile political colleagues of Thelwall’s like Erskine, Burdett, and Horne Tooke (all of whom appear in the print), the Satirist’s suggestion that a little Thelwallian eloquence and grace wouldn’t go amiss was sharply observed. Grenville’s political failings, it is suggested here, were compounded by his lack of figure as much as his defective oratory, and it is as appropriate to Thelwall’s holistic theories of vitality that Grenville must submit to having extraneous flesh carved from his buttocks to improve his balance, as it is for Lord Henry Petty to be taught how to stand for dancing by Thelwall’s wife. The failure of men like these to carry political argument is signified most clearly by the ungainly oratorical attitude of Thelwall’s old adversary, William Windham, so unsuccessful in his attempts to shame ministers over the British bombardment of Copenhagen that a bust of Demosthenes falls from the wall behind him.

Thelwall’s failure to recapture the political limelight when he re-emerged into public life at the end of the Napoleonic Wars can be measured by the indifference of the early nineteenth century caricature trade after the death of both Isaac Cruikshank and Gillray. Thelwall came out of retirement to lend support to the moderate reformer John Cam Hobhouse at Westminster during the election of 1818 and spoke on a number of platforms as a “veteran” reformer. As the newly appointed editor of The Champion newspaper, he appeared occasionally in satirical prints as a wizened and ineffectual figure in the radical crowd, in stark contravention of suggestions in sympathetic journals like the Monthly Magazine that his return to the political stage was “characterised by his usual eloquence and energy” (48 [1819]: 566). George Cruikshank included him in two caricatures during these years, The Funeral Procession of the Rump (1819), and Coriolanus Addressing the Plebeians (1820), in the first of which his sorry figure traipses along in the wake of Hobhouse’s election defeat, expressing itself “ashamed of [his] company,” who include not only Burdett but some unidentified “acquitted felons.” In the second, he lines up with the radical crowd’s more moderate wing (the elderly Cartwright, Hobhouse and Hone), and looks more inconsequential than ever. Thelwall’s marginalised position in the radical canon reached new heights, however, in what was probably the last caricature ever to feature him, The Reign of Humbug (1825).

Fig. 20 George Cruikshank, The Funeral Procession of the Rump (1819). Photograph © S. Poole, image reproduction for non-commercial purposes, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Fig. 21 George Cruikshank, Coriolanus Addressing the Plebeians (1820). © The Trustees of the British Museum [Museum #1859,0316.152].

Fig. 22 Thomas Howell Jones, The Reign of Humbug (1825). Photograph © S. Poole, image reproduction for non-commercial purposes, courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

Uniquely, this was no loyalist print, but one composed as a frontispiece by Thomas Howell Jones for the radical republican William Benbow’s short-lived satirical journal, The Town. The very prominent Thelwall, posturing once again as a gentleman elocutionist, takes his place amongst a pantheon of public figures regarded by Benbow as modern irritants, time-wasters and imposters. Having taken fright and abandoned the Champion when the fiercely loyalist Constitutional Association threatened to prosecute him for seditious libel in 1820, and having at the same time loosened his political ties even with moderate men like Hobhouse, Thelwall was dismissed more readily than ever before by popular and less “respectable” stalwarts. In Howell Jones’s print, Thelwall has only his continuing association with the Monthly Magazine to (literally) support his compromised political apostasy, and finds himself surrounded by every kind of frivolous financial speculator, corrupt politician, disingenuous bishop and confidence trickster (including Brougham and Burdett) in Benbow’s firing line. In fact, he occupies a central position in a “humbug” world characterised in Benbow’s prospectus by “every species of imposture, dupery and quackery” and whose inhabitants “shall stand exposed in their native deformity.”

The wider public, to whom Thelwall had once directed his political energies, are shown facing away from his misdirected oratorical flourish to become dupes of the revived campaign against Catholic emancipation instead of making demands for reform. Thelwall’s irrelevant cry from atop his barrel, “My lectures on elocution . . . ,” goes, literally, over everyone’s head.

We may conclude then not only that Thelwall’s caricatured persona stayed consistently true to his actual physiognomy over a thirty year period (which is interesting in itself), but that, during the early years when it most mattered, both Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank—albeit in different ways—were far too interested in the apparent contradictions in their subject’s persona to reduce him unproblematically to an ugly Jacobin signifier like Paine. Thelwall emerges instead as a complex caricature, either a man whose slight frame, masked expression and quiet adaptability negate the strength of his oratory and reveal a political chameleon who is not, perhaps, the one-dimensional firebrand of popular construction, or alternatively a man whose credentials as a firebrand are unquestionable but whose darker motives and seditious character are far from clear. These ambiguities were only reconciled by Thelwall’s running to ground in 1797-98, due largely to the concerted efforts of the legislature, the connivance of the judiciary and the brute force of loyalist mobs. More than a decade ago, E. P. Thompson persuasively traced the multi-layered silencing of the “Jacobin Fox” in these terms, and it has been suggested here that both James Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank’s satires offer a visual commentary on the process by which this was achieved as well as the language in which it was expressed. However, the success of Pitt’s ministry in engineering the silence and defeat of Thelwall in 1798 has yet to be measured as a factor in his relatively unconvincing return to politics in 1818-20. The re-embodiment of the most feared democratic orator of the 1790s as the patron saint of lost causes, diluted principles and political humbug began in visual satire with Gillray in 1797. For all of Gillray’s oft-cited political ambivalence, his deflated Thelwall was perhaps of greater service to loyalist discourse than was Cruikshank’s alarmism, an approach to the problem that defied any obvious solution and which tended not only to question the effectiveness of the Gagging Acts but to suggest they had actually prompted clandestine plotting. Thelwall’s portrayal in print satire as the embodiment of radical defeat remained current for almost two more decades and did nothing to ease his assimilation back into the reform pantheon. Despite the re-energised mass platform movement for the popular franchise in the period between the close of the French wars and the passing of the Great Reform Act, Thelwall had come to stand for the failure of Jacobin aspiration. Alienated from former allies in the LCS like John Gale Jones and Alexander Galloway, who both threw in their lot with the new leaders of the reform movement—Cobbett, Hunt and even some of the Spenceans—Thelwall took his place alongside middle-class advocates for a limited extension of the suffrage and remained easy prey to charges of apostasy. For loyalist and radical illustrators alike, Thelwall’s reappearance in the early nineteenth century was marked by the forging of political alliances, as hopeless as they were disingenuous, and in the adoption of uncontroversial “professional” channels for the dissipated expression of what had once seemed a most terrible and dangerous energy.