Jean-Francois Lyotard argues that true learning can only occur once we begin to “learn to unlearn” our various expertises (101). Each time we return to a text or a question we must “recommence . . . [and] always begin in the middle” (100–101). This collection of essays, Teaching (the) Romantic / Romantic Teaching, would seem to bear witness to this fact; it might easily be retitled Pictures from the Scene of Unlearning. When Kate Singer and I first issued the call for this volume, we were interested in collecting essays that might have slipped through the cracks of our many themed volumes (Teaching Romanticism and Technology, Teaching Global Romanticism, etc.). The types of essays we were hoping for would examine new collective and individual intuitions of pedagogy, reimaginings of the concerns of cognition, language sensitivity, and world-making; in other words, we were looking for reports of pedagogical practice that shared certain premises about the world with the Romantic-era writers we write about and teach. If the kinds of “soul making” that Keats and Charlotte Smith engaged in was in a certain sense uncategorizable, then perhaps it should not surprise us that the ideas, techniques, and teachings through which its pedagogy is constituted might also defy categorization.

In any case, we were overwhelmed by the response to our call. We received far more excellent proposals than could ever fit into a single volume. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, when so many folks are doing such amazing work, we decided we wanted to create a more robust platform from which teachers of Romanticism could articulate and share their experience and intellectual labor. As a result, what you are now reading is volume one of a two-volume set.

Why all of this interest in pedagogy at this particular moment? One answer may be that when we are in the classroom, however that may look (my current classroom during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is virtual and distanced), we are best positioned to see the text from a new perspective and to discover a new relation of text to world. The inherent multiplicity of the classroom situation, and its ever-varying constituencies, makes this possible. As such, teaching holds open the possibility of seeing in new ways; it socializes the text by requiring that we continually “recommence” (Lyotard 105).

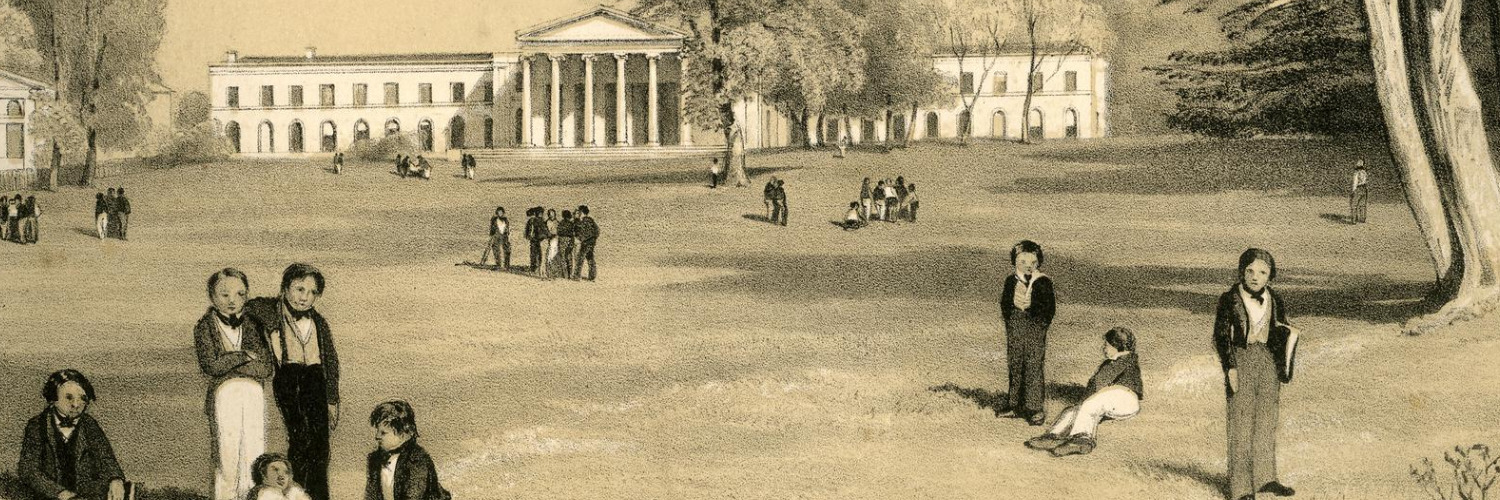

The essays collected here are keen examples of this revisionary and processual pedagogy. They ask us to reconsider our relationship to the two key moments of any pedagogical “project,” what was and what is yet to be (Sartre 91). As such, the essays in this collection move beyond mere contextualization. Sarah Maitland’s “Teaching Frankenstein in the Post-Columbine Classroom” narrates the efforts of her class to understand the social and psychic underpinnings of the Creature’s action by contrasting his narrative to fragments from the journals of the Columbine High School shooters. Catherine Ross’s examination of the curriculums of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century elite English schools not only enlightens readers of Romanticism by situating canonical poets in their own pedagogical milieu, but also suggests exercises designed to reproduce the effects and experience for our twenty-first-century students. One senses in these essays a profound commitment to the living history of a Romanticism that is constantly being learned and unlearned, sketched out, erased, complicated, and rewritten according to the ever-shifting exigencies of the political and pedagogical field. Also included in this collection are two excellent essays focused on poetry and poetics, each addressing a different aspect of verse practice or lyric theory. Elizabeth Walker’s essay, “‘Brown Study’ Aesthetics in Romantic Literature,” describes her attempts to reframe, with her students, Romantic-era practices of reverie and lyric production in terms of William Cowper’s poetic reflection as described in The Task. Carrie Busby’s essay, using Wordsworth as a model, focuses on the “acoustic ecologies” of Romanticism, past and present, suggesting that the reverberative effects of sounded-out poetic environments and subjectivities are perceptible on several levels in poetry, and, importantly, achievable in the classroom. Finally, we present two mixed-genre essays. Rachel Feder’s collaborative “field study” is a speculative essay composed with her students. It asks and addresses the question, what if, in Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, Marianne becomes pregnant when she and Willoughby visit Allenham House? Kathryn H. Warren’s contribution closes our volume. A full-throated defense of Romanticism as a living force, Warren’s essay asks us to bring all of ourselves into the classroom and to model for our students what it means to “take things personally.”

We are so grateful to all these writers for their originality, perspicacity, and courage, and are happy to be able to provide their essays with, if not a fixed and stable home, then at least a space that they can shelter in place.