In 1751, at the nascence of the print-saturated age that would continue to see unprecedented heights, Samuel Johnson invented a figurative use for the term ephemera in his Rambler 145. The insect whose life spans a mere day becomes equivalent in Johnson’s terms to newspapers, “the Ephemerae of learning,” those “productions . . . seldom intended to remain in the world longer than a week” (Johnson). Despite his defense of these writers of ephemera, Johnson’s turn of phrase nonetheless carries notions of death and decay. The printed page loses its value when it loses its immortality, Johnson reports, and when its production outstrips its longevity.

Johnson’s claim, though intended solely for periodical publications, presages the publishing boom to come. The Romantic period saw an explosion of printed material, ushered in by the end of perpetual copyright in 1774, new technologies that led the charge toward mass production, and the nearly insatiable appetite of a newly formed reading public.

There is debate over the extent to which this “reading revolution” is particularly Romantic, with H. J. Jackson making the case that literacy rates were on the rise before the Romantic period and mass production would not come until the Victorian age. Even if these technologies had not practically realized the boom in production and distribution of knowledge, their presence and promise changed the conversation about reading and publishing. We can reconsider the term “revolution” without denying there was considerably more print for Romantic readers and that readers’ engagement with any material could now be ephemeral. The concept of information overload far predates that contemporary term; in the Romantic period, like today, expanded access made the feeling more acute. Many Romantic readers felt the need, with the surfeit of information, to make their engagement more lasting. One way Romantic readers—and our students—could meet this need is through collection, and later indexing and reflection, in commonplace books.

Commonplace books allowed Romantic readers to confront the overload of printed pages by editing their own volumes, pushing back against the new technology through a deliberately antiquated and painstaking form of collection and transcription revived, as William St. Clair notes, from “the manuscript miscellanies of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries” (226). The desire to order information is not foreign to traditional student populations, millennials who are digital natives, or even the population I teach, nontraditional students in online and distance degree completion programs. The world is one where Buzzfeed has perfected the art of the listicle, programs like Pinterest and Tumblr allow users simple forums through which to bookmark, follow, and find. As the most popular search engine, Google’s stated mission is “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” Through adopting a sustained practice of commonplacing, my students and I position ourselves as best we can as Romantic readers, confronting in the internet age a similar expansion of ideas and information.

Asking students to inhabit the genre through an integrated and sustained set of hands-on activities that reimagine the means of traditional recall, synthesis, and analysis expands their grasp of the historical factors that condition texts. Commonplacing literally and figuratively collapses the distance between texts, drawing them into a conversation that resembles the way Romantic readers met these same works. We encounter our readings, not as discrete works of genius huddled under authors’ names in anthologies, but as part of a larger cultural conversation integrally tied to those who produce literature and to those who consumed and still consume these works. There is something powerful in confronting the materiality of texts—even, paradoxically, through digital means—that, at its best, empowers students as readers, collapsing the distance between their experience and what can seem so foreign.

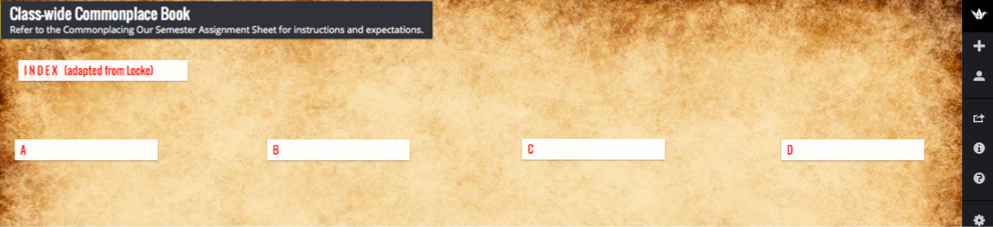

I developed the “Commonplacing Our Semester” project for an online course, English 411: British Romantic Literature, to be offered to students in an interdisciplinary degree completion program. The semester-long project pushes students to move from collection and organization to synthesis and reflection. Students keep individual commonplace books, contribute to a class-wide commonplace book, and reorganize and reflect upon their shared commonplace book in place of a traditional final exam. The purpose of these assignments is to foster students’ understanding of the historical and personal value of the commonplace book as a genre and to ensure students’ engagement with thematic threads within the Romantic period. I prescribe fixed parameters for the class-wide commonplace book, leaving the individual assignment more fluid and open to creative, yet still historically relevant, interpretations. As our commonplacing is a sustained project, I take pains to create continuity in style and structure across teaching materials, including assignment sheets and “quick start” guides for students (which are made available with this article, along with a reference aid for those interested in incorporating these assignments in their classrooms).

Students initiate their understanding of the genre though archival research of commonplace books housed in the Harvard University Library’s Open Collections Program and further their understanding through adopting the practice themselves. Students’ research informs their choice of purpose and technology for their individual commonplace books. The class-wide commonplace book takes John Locke as its model. Commonplace books allowed readers to amass information, similar to the way blogs and social media forums offer records or catalogs of information. Some Romantic readers, influenced by Locke’s popular treatise A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books (1706), used indexing to track commonalities. This added layer of organization was not an end unto itself; it was meant to spur further critical thought, with usefulness, according to Locke, the chief goal of commonplacing.

There are stellar examples of undergraduate commonplace book assignments using pen and ink, blogs or Pinterest, even an Atlantic article proclaiming “‘Commonplace Books’: The Tumblrs of an Earlier Era.”

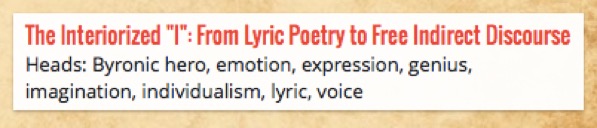

For the shared commonplace book, I use Padlet, a free note-taking program that may in comparison look rudimentary but allows users to manipulate the page beyond sequential readings or targeted searches for single items. Students transcribe weekly quotations, devising what Locke called “heads” for the index, motifs or tags for each quotation. Students refine their thinking in the final exam, which requires a further reorganization of the collected quotations and heads into thematic threads. To successfully complete the exam, students must return to our semester’s work to find common places among what they collectively and cumulatively have contributed. Looking back, they recognize patterns that have emerged in our thinking about Romanticism and how we might define Romanticism given our class’s concerns. Their accompanying essays take up issues of process—how and why students chose the themes they did—and consider Romanticism as both an intellectual movement and historical period. The two parts of the exam help students synthesize the wealth of material we have gathered over the course of the semester into manageable pieces that suggest larger questions of categorizing the Romantic period.

Curating an Online Experience

Effective use of technology is essential to my teaching, as most of my courses are taught either asynchronously and wholly online or through other distance means. The online course is its own genre, dependent upon the written word as its means of communication. In contrast to live discussion, participants, both students and instructors, craft and (ideally) have time to polish what it is they want to say. But reading 250 words is a different experience than hearing 250 words. My most successful online courses avoid attempting to replicate the experience of a live classroom. I attempt, instead, to embrace the genre, working within the limitations and the possibilities of the virtual classroom.

As online educators, we are curators of the learning experience. Embracing the medium through which we communicate with students involves not simply amassing information but reimagining it. The majority of my students are taking full course loads online, in addition to their 9-to-5 jobs, which require many more hours in front of a computer screen. Not only do I organize learning modules with information overload in mind, but I also draw this concept into the virtual classroom. With its dependence upon the written word, our digital medium reflects commonplacers’ active engagement with written text. Even the social aspects of commonplacing—circulating the book among friends, transcribing a favorite line or penning an original verse for its owner—use written modes of communication. We, too, rely on the written word.

In my experience, providing students with as much detail as possible about major assignments upfront—despite the potential for information overload—assuages student fears in an online learning environment. I introduce the semester-long engagement with commonplace books in the course’s first learning module with a lengthy assignment sheet I title “Commonplacing Our Semester.” (Link to the full document through Figure 1 below.)

The introductory sections of this assignment sheet link Romantic reading experiences with our own, specifically through the “Consider while Commonplacing” box on page 2. This part asks students to consider modern equivalents of commonplacing through tagging, sharing to save, and bookmarking, while introducing terms common in modern conversations about technology—information overload fatigue and information literacy. The last page of the assignment sheet reassures students that feeling information overload is an intentional part of our learning experience.

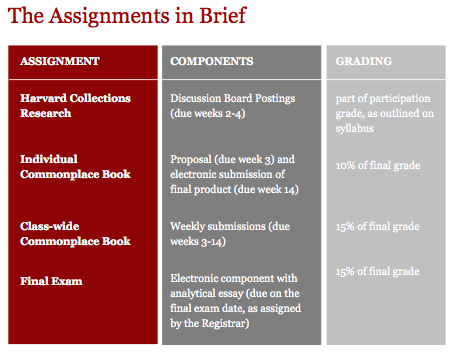

After a brief introduction to commonplacing as a Romantic practice, the assignment sheet details the four component parts of the semester-long project: archival research of primary source material; an individual commonplace book that students propose and keep throughout the semester; a class-wide commonplace book they share digitally with their colleagues; and a final exam that requires reorganization and reflection upon the shared piece. Despite my desire for transparency, I leave off details of the final exam until late in the semester so that students’ commonplacing stems from their experience of the weekly readings and our exploratory discussions, not from a prescribed end goal. These four components total a little over 40% of students’ final grades, as explained in Figure 2 below, with the remainder of the semester’s final grade divided among a close reading essay (20%), researched argument (25%), and participation on discussion boards (15%).

I am keenly aware that assignment sheets, especially in a wholly online format, can add to information overload. But a digital classroom does not allow for asides and clarifications that occur when reviewing a document in person. Structure is key to producing materials that are thorough yet manageable. Repeated visual elements within and across the two assignments sheets underscore significant requirements and guide students to see the project as a whole.

Understanding the Genre: Harvard Library’s Open Access Collections

Commonplacing allows students a way to arrange information and empowers students to feel a sense of ownership over this knowledge. To ground students in the practice of commonplacing, I assign two short and digestible readings: William St. Clair’s brief historical overview of Romantic era commonplace books from The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period (224-29) coupled with the homepage of Harvard’s commonplace book digital archive. I require little secondary reading so that students’ understanding of the genre comes from their archival research into the nearly 100 commonplace books digitized by the Harvard University Library’s Open Collections Program as part of its Reading collection.

Large digitization projects like Harvard’s make the kind of work I propose here possible for larger institutions and for students whose resources may be limited. Harvard’s open-access resource offers millions of digitized pages, curated into six themed projects. The project we use, the Reading collection, houses manuscript and printed material related to reading as a solitary and social practice, including a subsection for commonplace books. But these projects themselves represent a glut of information that can overwhelm the online learner accessing them on a home PC.

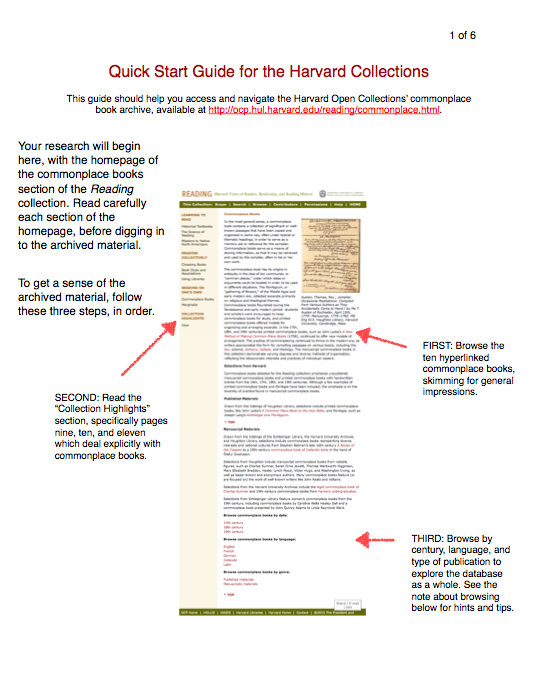

To ease this potential information overload, I developed a Quick Start Guide to the Harvard Collections (linked below in Figure 3) with visual steps for accessing and navigating the archive, along with explanations of Harvard’s terminology, tips for the site, and links to pertinent Romantic materials. Harvard’s selections span the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries and five languages, in both printed and manuscript forms. The database provides digital surrogates, often without transcriptions or translations, which can be daunting for undergraduates. Few of the books themselves are fully searchable, but the links on the commonplace book homepage can focus students’ individual efforts. For example, as shown in Figure 3 below, I direct students to read first the ten commonplace books linked in the overview section on the homepage. I then ask that they explore the Reading “Collection Highlights” (specifically pages nine, ten, and eleven which deal explicitly with commonplace books) before searching by century, language, or type of publication and navigating one by one the full list of items.

The purpose of this research is not necessarily to engage the content of the commonplace books but to recognize the forms these books take. The assignment sheet guides students’ research, asking specific questions, inset on page 5, to help them recognize visual and organizational patterns. Even if students cannot always read the language (or the handwriting), what comes into focus is that there is variety within accepted formats. Students share their findings through discussion board posts from which we craft a working definition of the genre.

Students find that while all were repositories of information for later reflection, some commonplace books were also scholarly tools, study aids, or means for inspiration, both professional and personal. They contained clippings and transcriptions, sketches, and, as Hester Lynch Piozzi playfully titled hers, Minced Meat for Pyes and Scrap & Trifle. They ranged from beautifully ornate to messy and chaotic. The Reading “Collection Highlights” section explains, “Each commonplace book was unique to its creators,” and, yet, they belonged to a distinct category with recognizable forms.

Applying the Theory: Individual and Shared Commonplace Books

Once we have compiled a rough definition of the genre, we move to practices of commonplacing. The freedom within boundaries that characterizes Romantic commonplace books is why I assign two forms: the individual and shared commonplace books, both requiring weekly entries that engage that module’s readings. The individual commonplace book’s grade is based on a brief proposal and electronic submission of the commonplace book in full at the end of the semester. Even if students wait to compile all entries at the close of the semester, they will still meet the goals for this component: self-directed engagement with assigned readings and parsing connections between the historical facets of the genre and modern resonances of commonplace books.

The assignment sheet’s section “To Consider When Writing Your Proposal” suggests possible purposes, entries, and technologies to guide students’ proposals, but they are not bound by these suggestions. Students, like their Romantic predecessors, may choose to collect only particular types of material (poetry, for example, like this nineteenth-century collection of ballads) or group their collections thematically, as did eighteenth-century commonplacer Thomas Austen in separate manuscripts on poetry and plays, religious poetry, theology and philosophy, and devotional literature and sermons. They may choose material related to their area of study or future profession in the vein of Charles Sumner’s example in which he not only compiled his own commonplace book centered on law, but also published The Lawyer’s Common-place Book, with an Alphabetical Index of Most of the Heads which Occur in General Reading and Practice.

Or the book might be intended for someone else as in Hester Lynch Piozzi’s commonplace book collected for her adopted nephew John Salusbury Piozzi. Students’ individual collections, like many commonplace books in the Romantic era, might confine themselves to sententiae, whose quotations out of context comprise little more than inspiration for the collector.

These individual commonplace books—while they must engage Romanticism and our semester’s readings—should move beyond that as well, with a clear focus of their choosing.

The students’ shared commonplace book, on the other hand, returns to one of the original and more canonical uses of the genre—as study aid—and adopts a prescribed format taken up by many commonplacers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, one adapted from John Locke’s A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books (1706). This guide contains a letter written by Locke detailing his method of commonplacing, along with the recipient, Jean Le Clerc’s, prefatory advice for commonplacers, both of which I assign to students.

This method became so popular that publishers printed commonplace books “upon the plan recommended and practised by John Locke,” such as the ones Ellis Gray Loring and George Ripley kept, and, in 1831, Charles Sumner published The Lawyer's Common-place Book based on Locke’s formula, all of which I ask students to reference.

Locke and Le Clerc assert the usefulness of commonplace books—that “it is of Service to have Collections of this Kind, both that Students may learn the Art of putting Things in Order, as also the better retain what they Read” (sequence 13). What Locke adds—and what publishers later capitalize on—is a clear methodology for keeping an index.

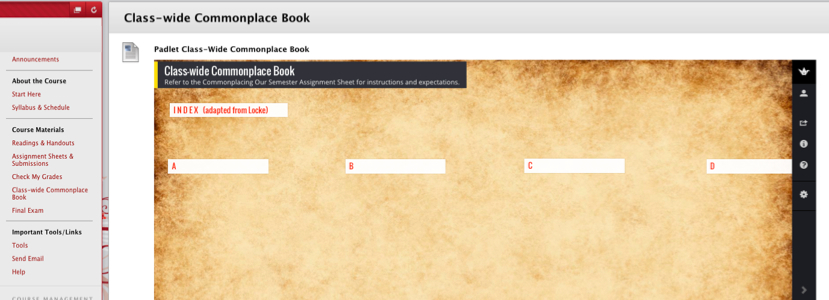

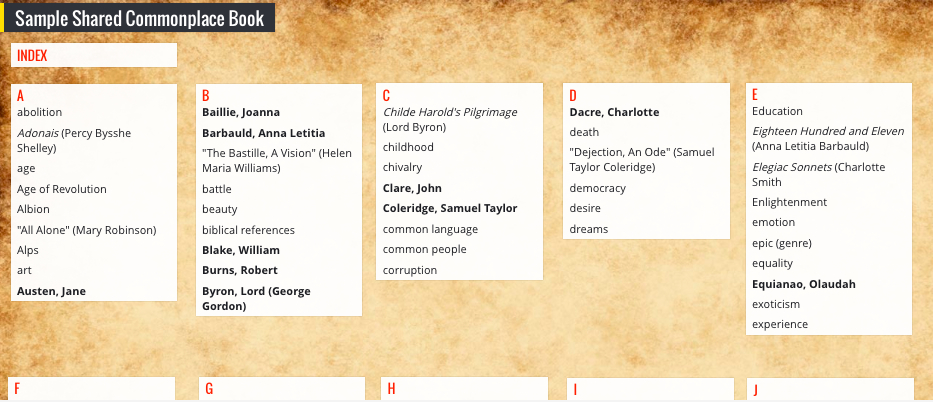

This organizational principle, in brief, involves an index with what Locke calls “heads,” what literarily we would call motifs, or, on the internet, tags. (I consciously use the term “heads” since a primary learning outcome for this component is for students to apply practically Locke’s theory.) Locke’s method, in its most simplified form, is as follows: at the beginning or end of the book, the commonplacer designates blank pages with alphabetical columns into which heads are accumulated, as seen below in Figure 4. When adding content throughout the commonplace book, the commonplacer keeps running heads in the margins of the pages that are then cross-referenced in the index with the page number. Even in our simplified form (explained in more detail in the next section), indexing requires students to move beyond note taking to employing pattern recognition and engagement with literary motifs. “Locke’s ‘New Method,’” Stephen Colclough notes, “still encouraged readers to record extracts from their reading under headings, but these were now to emerge from their reading rather than dictate it” (33). My students, like the Romantics before them, engage in an active process of reading and interacting with material collected that results in an intentionally ordered book instead of a dizzying collection of quotations with little use beyond their initial transcription.

![Image taken from page 496 of 'The Works of John Locke, etc. (The Remains of John Locke ... Published from his original manuscripts.-An account of the life and writings of John Locke [by J. Le Clerc]. The third edition, etc.) [With a portrait.]', uploaded on Flickr by The British Library.](/sites/default/files/imported/pedagogies/technology/images/jones-4Thumb.jpg)

Commonplacing in Action: Organizing with Padlet

In my online classes, we translate Locke’s method for commonplacing using Padlet, a free note-taking program.

Locke and Le Clerc argue that commonplace books are not solely a repository of knowledge but are meant to be useful, with that usefulness dependent on indexing. Padlet, unlike sequential repositories of information like Tumblr or Pinterest, offers a more seamless way to adapt Locke’s method. Padlet provides a digital notepad whose virtual surface allows users to order more readily its contents.

The interface is user-friendly: double click to add a textbox and drag and drop to move textboxes or to attach links, audio, video, documents, other padlets, and more. As with any new program, getting used to the interface provides certain challenges, even for those who routinely take online classes. Like with the Harvard Collections, I provide a Quick Start Guide for Padlet (linked in full in Figure 5).

I recommend Padlet as well because any wall can be embedded into an online learning management system (like Blackboard or Moodle) or class website to better integrate the learning experience, especially for students who may be accessing the class from multiple devices. I compiled a Quick Reference Guide for Instructors Using Padlet (linked in Figure 6 below) for Romantic Circles readers who may wish to incorporate parts or all of this assignment into their classes. It explains general usability and describes Padlet’s features, while also providing step-by-step visual instructions for how to prearrange and embed a Padlet wall to use for the class-wide commonplace book assignment. Even if students house their walls on Padlet’s site, instead of creating an embedded wall in a course’s management system or website, there are multiple levels of privacy, from password protected to public, with an unlimited number of users whose level of access can be tailored through permissions. There are options to send emailed notifications when users modify a wall, and, if not embedded, URLs are customizable (with student names for their individual commonplace books, for example).

After completing research into Locke’s method of indexing, specifically by reading Locke’s guide and referencing commonplace books styled after his method linked in the Commonplacing Our Semester assignment sheet, students begin weekly entries on our Padlet wall. Each entry consists of two parts: a single quotation from that week’s textbook reading and “heads” (Locke’s term for motifs or tags) added to the index that the student generated for this quotation.

To prepare for weekly entries to the class-wide commonplace book, I prearrange and embed a Padlet wall with the index, consisting of separate text boxes (what Padlet terms “posts”) for each letter of the alphabet, followed by a subheading for weekly entries, as shown in Figures 7 and 8. One shortcoming of Padlet is that the virtual surface stops immediately after the last post, which impedes maneuverability. I add a “placeholder” post, seen in Figure 8, dragging it down the page until there is ample space for students to add entries.

The basic form of an entry, seen in Figure 9, includes three parts: a student’s name and module week number in the title line; the material from that week’s reading the student wishes to contribute; and a list of running heads, which are the motifs the student assigns to the passage quoted. I limit the length of quotations (10 lines for poetry, 250 words for prose) to keep the page manageable and to avoid another potential form of information overload. I offer bonus points for students who add heads to their classmates’ posts, denoted by their name in parentheses after the head, as in the figure below where Student B has added “innocence” and “experience” to another student’s entry. Padlet also offers an unobtrusive way to attach documents to text box entries with explanations as to why students selected the particular passage.

The second weekly requirement is to add the heads students have generated to the alphabetical index at the top of the wall, along with entries for author (in boldface) and title (styled according to MLA rules and followed by the author’s name in parentheses), as in Figure 10. Students must be diligent about checking the index so as to add heads created by classmates that they might not have considered, but which are relevant to their contributions.

Whereas printed commonplace books allow for page numbers to be added to the index, Padlet’s digital surface provides a continuous screen, unbroken by discrete sections. To replicate the cross-referencing gained through pagination, I ask students at the end of the semester to further organize the class-wide commonplace book so that entries are grouped according to larger thematic concerns germane to our ongoing discussions of Romanticism. This final requirement of the semester-long commonplace book assignment (which counts as the final exam) has two graded parts: the reorganization of quotations and heads on Padlet and an accompanying essay explaining students’ rationale for this new organization. The exam requires students to choose thematic threads to act as umbrella concepts under which the accumulated quotations and heads could be housed. I limit the exam to six to eight thematic threads, with all heads distributed among the themes and only five quotations assigned to each. The final exam assignment sheet, available under Figure 1, explains this process in further detail. Steps for realizing this assignment in Padlet are included in the Quick Reference Guide for Instructors Using Padlet.

One benefit of this assignment is its cumulative nature, which happens by way of students returning to our class-wide commonplace, not for revision but for reimagining, informed by the whole of the semester and the work of classmates. In this, the assignment may realize the best of what we would hope from all of our social media: the collection and distribution of knowledge that gains from its communal nature new perspectives on that which is shared.

A Common Reading Experience

In a digital age, we confront, as Romantic readers did, the limits of media. How does—or should—one preserve ephemera? What does it mean to collect within a digital medium—a repository that is intentionally not tangible, unable to be physically held or even held in the promise of perpetuity? One way to address these questions is to adopt a means of collection that is less passive than the now familiar modes of bookmarking, sharing to save, and tagging.

Reflecting a practice Romantic readers perfected, our commonplacing combats information overload. It also allows for a sense of ownership over material students often feel distanced from, a feeling shared by Romantic compilers, many of whom were excluded from purchasing printed books but who could fashion their own via commonplacing. Romantic commonplace books reflected their compiler’s individual tastes but, paradoxically, were also “frequently the work of multiple hands and circulated among multiple readers within particular circles of friends” (Lynch 137). We, too, compile our own texts, sharing not only insights gleaned from the texts but also the act of creation. Using the means available to us in the digital age, we embody, as best we can, the place of Romantic readers.