This essay comes out of our collective experience as an instructor (Michelle Levy) and two students (Ashley Morford and Lindsey Seatter) in a blended class (consisting of undergraduate students and graduate students) taught at Simon Fraser University in the summer of 2014, a course that was redesigned, and retaught, in the summer of 2015. This course, “Reading the Literary Manuscripts of the Romantics,” required students to complete a final digital project. In what follows, we explore the reasons for assigning a digital project as well as the opportunities and challenges that we encountered. Throughout the essay and in our conclusion, we provide a series of pedagogical guidelines based on our experience that we believe can improve student learning. We have also developed a companion website, Digital Projects in the Romantic Classroom which we hope will be of use to instructors contemplating integrating digital projects within their own pedagogy. The website includes descriptions and links to model projects created in both the 2014 and 2015 iterations of the course, video tutorials that demonstrate the basics of digital site design, various course materials, and an extensive bibliography.

Course Objectives

ML: “Reading the Literary Manuscripts of the Romantics” is an upper-division course focused primarily on five authors (Jane Austen, Lord Byron, John Keats, Mary Shelley, and Dorothy Wordsworth, with some attention to Percy Shelley and William Wordsworth as well). The course readings are designed to engage students with questions of textuality and textual migration, to study how literary works transitioned from one media (usually script) to another (usually print). We also read texts (such as Dorothy Wordsworth’sGrasmere Journals and Jane Austen’s juvenilia) that were not published during the authors’ lifetimes to ask why they were withheld from print, or better yet (and to quote Margaret Ezell), what are authors “attempting to do” by disseminating their works in handwritten form (23).

My own research in media history, and in particular the varieties of media by which literary texts were disseminated in the period, informs the nature of the investigations we undertake in the course. Students are asked to interrogate the texts they read in their anthologies and critical editions, to reconstruct the complex textual history that is usually omitted in student editions, and thus to consider how the material forms in which these texts circulated affect meaning. In other words, I want students to think about the interactions between linguistic and bibliographical codes (McGann 56-57).

Although we typically associate the Romantic period with the technology of print, manuscript production was ongoing, and not only in the sense that almost every print work necessarily began as a handwritten document. Manuscript production and circulation continued as it had for generations, as an alternative to print—for material that was intended for a social readership, or otherwise too risky for print. Scholars like Peter Stallybrass have in fact argued that print created more opportunities for manuscript production—a dramatic rewriting of the narrative of media succession, whereby a new technology (like print) is seen as replacing an older technology (like manuscript). Very recently, we have seen that digital media, contrary to expectations and predictions, has not replaced the printed book. Rather, print and manuscript, like print and digital media, are interdependent, though in the Romantic period the abundance of print has meant that we often lose sight of how authors persisted in their use of the older technology of script.

Digital media offers great promise because it makes the study of manuscripts far more accessible to researchers (including students) than they ever have been. Furthermore, digital resources and digital assignments allow students to represent manuscript far better than is possible in the print essay, as linking and screen shots enable students to draw the original manuscripts into their own projects in new and exciting ways.

The Romantic period offers rich opportunities for the exploration of these questions of textuality and mediation. It is no accident that many of the leading textual theorists of the last fifty years—Jerome McGann, Donald Reiman, Jack Stillinger, and Kathryn Sutherland, to name only a few—have developed their theoretical interventions through the study of the physical manuscripts and printed books of Romantic authors. Their editions, as well as their theoretical work in the field of textual scholarship, are a result of the extensive manuscript (and print) record that survives. Romantic authors were one of if not the first generation of writers for which manuscript witnesses survive in profusion, allowing for the reconstruction of textual history in ways that are impossible for previous generations of authors. Further, many of our period’s authors were inveterate tinkerers, both in manuscript and print: Wordsworth, for example, constantly revised his texts over his fifty-plus-year career; Mary Shelley substantially re-revised Frankenstein thirteen years after its first appearance; and, according to Jack Stillinger, some eighteen versions survive of Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (v).

In addition, authors of the Romantic period were acutely aware of their audiences, and how medium affected the reception of literary works. Robert Southey’s comments on the piracies of Don Juan expresses this understanding perfectly: “‘“Don Juan” in quarto and on hot-pressed paper would have been almost innocent--in a whitish-brown duodecimo, it was one of the worst of the mischievous publications that have made the press a snare” (Senior 128). I want students to grapple with the understanding that Southey expresses—that a text published in one format (expensive quarto) could be perceived to be “almost innocent,” whereas the appearance of the identical text in another format (cheap duodecimo) was deemed “mischievous,” even dangerous. Countless other examples could be found: the effect of reading a poem in the author’s autograph offers a different experience from than reading the identical poem in a newspaper, a print collection, or an author’s collected works. I also want students to engage with the reasons why authors might elect to circulate their literary texts in handwritten form, and to explore patterns of textual movement. A poem might, for example, be first exchanged in manuscript within a coterie, and then subsequently printed. Alternatively, it might be printed and circulated in manuscript simultaneously, or the reverse might be true, as when poems were copied from print. Authors also often shuttled their texts between different print forms – consider Charles Lamb’s “Elia” essays. They first appeared in the London Magazine, and then were collected for separate publication in book form. The two versions are not only textually different, but they also carry different bibliographical signification as well. Ultimately, the course aims to involve students as much as possible in reconstructing the linguistic and bibliographical codes that imbue texts with meaning.

Benefits of a Final Digital Project:

ML: In previous undergraduate courses, I had offered students the option to submit a final project in digital form rather than as a standard print essay, and I had always been pleased with the results. As the digital project was not required, it was taken up by interested students but passed over by most. This result is not surprising, since I offered little formal instruction, with students mostly forced to fend for themselves in the construction of a digital project.

With the summer 2014 iteration of “Reading the Literary Manuscripts of the Romantics,” taught in the summer of 2014, I decided to make the final digital project required. There were several reasons why I thought the time was ripe for such an approach. In the first place, although the course is focused on literary manuscripts of the Romantic period, my students would not be in a position to view, in person, a single physical manuscript discussed in the course. Indeed, a course like this is only possible because of the release of digital facsimiles and editions of manuscript material, particularly Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts, Romanticism: Life, Landscape, and Literature (featuring the Wordsworths’ manuscripts), the Shelley-Godwin Archive, and the Harvard Keats Collection.

These sites all provide access to photofacsimiles of manuscripts of major authors, some with transcriptions. Thus, by necessity, students would be using digital materials and, as a consequence, students would have to be taught to become conscious and critical of the effects of digital remediation. Asking students to construct their projects within a digital medium seemed a natural outgrowth of this engagement with media history and digital material. As we explored the ways that texts historically migrated across media platforms, students were primed to explore how their own writing could be disseminated and might be transformed by the use of digital platforms. Finally, because their primary source material was in digital form, and because manuscripts are expressively visual, a digital platform would enable students to incorporate these resources in a digital project far more easily than in a traditional print essay.

AM and LS: As graduate students, we found that one of the most substantive benefits of creating a multimodal digital project was that it could serve as the foundation for an evolving research portfolio. Instead of drafting a standalone final essay, which is generally the culminating assessment for courses taught in the humanities, a digital project provides a space for creating and collecting scholarly research over an extended period of time. This means that the assignment has a life beyond the initial classroom evaluation and can become a platform for showcasing our work in alternative academic and non-academic settings (Hess 34). Conceptualizing digital projects as evolving portfolios can also serve as a springboard to graduate studies or to work opportunities both within and beyond the academy.

Another benefit beyond the classroom is that students can make digital projects more widely accessible. For instance, if a student makes their digital project public (as with a website), their work is openly accessible to larger populations and subject positions. The visitor statistics for Ashley’s Frankenstein: Troubling Understandings of the Other project offer a small example: in the first year that the project whas been up and running, it has received a wide range of visitors from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Qatar, Spain, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Many of these visitors have discovered the website through search engines. Some visitors have been professors, others have been students working on Frankenstein-related class projects, and the subject positions of many other visitors remains unknown. Even if a student does not make their project public, they can control access by inviting others to view it. Thus parents, friends, fellow students, admission committees, and potential employers can observe and engage in student research and writing that is usually confined to the classroom, thereby making visible (if only to a confined circle) the benefits and skills associated with our discipline.

By design, the format of a digital assignment—its fluid, easily mutable existence—invites students to continue editing, revising, and enhancing the material presented online, even after the course is complete. This invitation—coupled with the strong sense of ownership students feel over work that has evolved directly from their own research interests—can motivate the continual development of the project. This has been our collective experience. For example, Ashley has continued to re-imagine, edit, and alter her site during her doctoral studies. For example, Ashley is now developing her site into a doctoral project. Lindsey’s project, Digitizing Literature, has evolved from a classroom assignment into a culminating Master’s project and, more recently, into a professional portfolio that showcases a history of academic work. Looking back on the development of these projects demonstrates an evolution of student-led research.

When students direct their own research, they gain a sense of ownership over their work and leadership over their academic program. Our digital projects have been key components of our admission to doctoral programs and our hiring into research positions. We have found that showcasing a digital project as part of a curriculum vitae evidences that a student possesses skills as both a traditionally-trained and digitally-literate scholar.

Because digital projects have the potential for a life beyond the scope of a semester, they can serve as a bridge towards professionalization. Working in the Romantic period, we are lucky to inherit a prestigious lineage of innovative digital scholarship. Aggregatione project sites such as Jerome McGann’s NINES and Laura Mandell’s 18thConnect represent the vast and varied multimodal projects taking place in Romantic literary studies. For students who pursue their digital projects beyond the classroom—evolving their work into honor’s theses, graduate projects, or professional research interests—preserving their work under an umbrella such as the Advanced Research Consortium (ARC) may be held as the ultimate goal. Not only do these sites provide opportunities for peer review, they also enable connections between individual projects, promote standards, enforce professional practices, and perpetuate an online identity of rigorous scholarship. Professionalization can be neglected as an objective of academic coursework but by creating assignments that develop the “skills, identities, norms and values” associated with quality digital work, the classroom can become an arena for digital humanities credentialing (Rockwell and Sinclair 177-178). The professionalization skills gained in the creation of digital projects can offer opportunities outside of the academy as well. For instance, both Lindsey’s and Ashley’s digital projects have resulted in opportunities to build WordPress sites outside of academia.

ML: Students who do not continue into graduate work (who and these students comprise the majority of our my students) also benefit from their involvement in digital projects. If one of our strengths as a discipline is teaching our students how to read and write critically, we must also recognize that as the media ecology we inhabit shifts and print loses its former dominance, “print, essayistic literacy” will also have to adapt (Williams xii). Written communication increasingly takes place in digital forms, and we can take the lead in not only teaching our students how to read and engage with online materials, but in how to produce them. Indeed, it seems that it should be part of our mission to teach students how to write—cogently and expressively—for online media, skills that they will need “if they hope to communicate successfully within the digital communication networks that characterize workplaces, schools, civil life, and span traditional, national, and geopolitical borders” (Takayoshi and Selfe 3).

AM and LS: In addition to providing a life beyond the classroom, we believe that digital projects provide students with the opportunity to pursue their own research interests, to approach familiar texts with a fresh perspective, and to experiment with new methodologies. While these pursuits are attainable within a traditional print essay, there is an aspect of play and experimentation with digital project creation. As Bonds suggests, digital experimentation and play allow students to develop more fully, to discover and produce their own knowledge rather than simply mimic the knowledge of a teacher, which can happen when students write traditional essays (Bonds 150).

The initial experience of creating in a digital space can be disorienting for traditionally trained humanities students. However, learning to work within a new digital platform like WordPress and having to approach a research project through a new medium can be exhilarating, leading to revitalized engagement with the material being studied and expanding the methods that students can draw on to present and communicate ideas. As the model projects demonstrate, the opportunities to play with, experiment with, and incorporate the digital through hyperlinking, adding multimedia, and personalizing design aspects (like header images) give these assignments more scope for creativity and for engagement with primary materials than is typical in traditional assessments. Additionally, the digital platform offers students the opportunity to oscillate between creative and critical work as they face the new challenges of site design and media integration alongside the more familiar tasks of close reading and scholarly commentary. This balance is often missing from traditional assessments where students are limited to working within a word processing document that will be printed on paper.

Yet it must be acknowledged that the print essay continues to have some benefits over the digital platform. There is the familiar argument that reading from a printed text allows for better retention of information than reading from a digital text does, that “the physicality of a printed page may matter for those reading experiences when you need a firmer grounding in the material. The text you read on a Kindle or computer simply doesn’t have the same tangibility” (Konnikova para. 5). Additionally, in terms of the writing process, digital platforms like WordPress lack simple, clean ways to incorporate footnotes or endnotes; while MLA formatting helps to alleviate this issue, as it encourages in-text parenthetical citations, the ability to incorporate discursive footnotes or endnotes remains a challenge. Further, while it is easy to continue to develop digital projects on platforms like WordPress, the print essay is, of course, by no means stagnant; class essays can develop into conference papers, which can develop into honors theses or (for those few students who continue on in academia) graduate capstone papers, which can develop into journal articles, and so on. Indeed, the first assignment of this course is a traditional print essay, which students were encouraged to use as a springboard foundation into for their digital project.

The ability to work directly with a range of online materials—digitized manuscripts and rare books, video clips and images—can also help reorient the usual instructor-student hierarchies by refiguring the student as the creator, instead of merely the receiver, of information. In our course experience, the ability to work directly with digitized versions of unique primary sources moved us from the position of student to the position of researcher. Interacting with these materials, which are locked in exclusive manuscript vaults thousands of miles away from our classroom, would have been impossible without leveraging our access to their digital surrogates.

Pedagogical Challenges of Digital Assignments:

ML: When I began to teach courses with digital projects, I had fairly rigid expectations of what they would look like: a digital edition of literary text. Practically speaking, students were advised to select a short text that had been somewhat overlooked in the scholarship (so that they could master the critical background). Ironically, given what I thought to be my attentiveness to possibilities of new media, I imagined students creating digital editions that were based on a model of the print edition; specifically, I had Broadview Press’s literary editions in mind. Having edited a critical edition for Broadview, I was familiar with this format and esteemed it as a pedagogical model, with its richly historicized introductions, annotations, and appendices of primary material. Several students followed this model, choosing to develop editions of shorter works (such as short pieces from Austen’s juvenilia, Austen’s later manuscript fiction, or little-studied essays by Anna Barbauld).

Nevertheless, I realize now that, in imagining the output to be a digital edition, I was inadvertently applying a print-based model, and one that imposinged unnecessary limitations on the kinds of projects students could pursue. I also overestimated my ability to provide students with adequate instruction on editorial theory, which proved too difficult to teach with proper rigor in a course with so many other balls in the air. Fortunately, most of the students navigated (or circumnavigated) this aspect of the project. Some did so by selecting texts that exist in only one version, a highly sensible solution that avoided many thorny editorial issues. Others, who were dealing with texts that survive in multiple versions, rather than fixing on (or creating) a single edition, instead sought to study those very issues of migration and change between versions. Thus, many of the final projects were not editions at all, but essays constructed in digital space that analyzed different versions of a text. For example, Ashley’s project considers Percy Shelley’s revisions to the draft manuscript of Frankenstein; others, such as Lindsey’s, examined the transition of Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere Journals from their manuscript sources to the early print editions (edited by William Knight and Ernest De Selincourt) and into excerpts used in current teaching anthologies. Many of these projects succeeded in enabling students to think critically about textuality. And projects can also emerge that are less textually-focused but rather seek to curate and thus explore critically a small selection of related poems, such as Byron’s separation poems, or Percy Shelley’s poems to Jane Williams.

In teaching the course for the first time in 2014, I still did not fully overcome the false assumption of digitally-savvy students. Jim Mussell debunks this common assumption, explaining that “the technical competence of the young is routinely overstated” (203). By treating the digital assignment as similar to a print essay, I failed to realize that students would need more guidance at each stage of the process and would require more time to prepare their final digital project than was necessary for a print essay. I had invited Matt Huculuk, from the University of Victoria, to offer a workshop on the use of WordPress, but that was about halfway through the semester: had it been held earlier, it may have assuaged student anxiety about the technical aspects of the project. Unlike a print paper, which students (at this stage in their academic career) can draft very quickly (if circumstances require), a digital project requires a longer timeline, with more opportunities for experimentation and failure, and with more time for planning and design.

In the second iteration of the course, in 2015, more time was devoted to technical skill development. I was fortunate enough to have Lindsey and Ashley serve as “digital coaches” (see Branscum and Toscano 95-96) for my students, and we are hoping, with the Digital Projects in the Romantic Classroom website we have created, to offer this kind of digital coaching to other instructors and students. One other way in which we have attempted to overcome the technical learning curve has been to reconceive the course as a series of cumulative assignments that build towards the final digital project. The challenge has also been to convince students to take a longer view of their coursework; from the instructor’s perspective, I had to overcome the practice of conceptualizing assignments as discrete units, a practice driven in part by a concern that the students should not be able allowed to reuse work from a previous assignments.

One other pressing issue that arose in contemplating the assignment of a digital project was the question of what platform to use, and with that, of sustainability. Originally (and as part of my edition-based thinking), I wanted to find a platform that was oriented to scholarly digital editions, one that might even allow for students to use TEI-XML for their projects. Although there are a few platforms in development that will allow for the implementation of TEI markup—including CRWC-Writer and Islandora Critical Edition—none are currently available for implementation. WordPress—being extremely easy to use, open source, and free—had much to recommend it. It had been successfully used by Matt Huculuk in his undergraduate courses, and these projects were viewable by my students as potential models.

Additionally, I was using WordPress for the course website, so students would necessarily become familiar with how to use its basic features. I also made my peace with the issue of sustainability; for reasons already articulated by Ashley and Lindsey, a digital project built in WordPress is likely to be more durable and extensible than the ephemeral student essay, which has little hope of reaching an audience beyond the original instructor, and no expectation of survival beyond that term, or, at most, the life of the computer hardware on which it is written. Perhaps somewhat paradoxically, WordPress might offer a more stable archival structure than its traditional counterpart.

AM and LS: For many students in the “Reading the Literary Manuscripts of the Romantics” class, WordPress was an unknown and, therefore, unexplored platform. Reflecting on the summer 2014 course, key aspects of a WordPress project— such as the ability to make static pages, parent pages, and child pages—were confusing for some of us to learn, and extra time, care, and external research/reading of online documentation or user message boards was needed to ensure that we understood these components. The intense anticipation of the technical learning curve that precedes the development of a successful digital project is often enough to discourage experimentation within this new medium. In addition to the learning curve, a digital platform, like a website, will often not reflect the same linear structure of a traditional essay through its mandatory introduction, body, and conclusion. As humanities students, many of us have years of experience composing argumentative papers for print and the vast majority of, at least, upper division students find great success and enjoyment in working within this genre of assessment. While the standard academic essay has proven over time to be a useful argumentative tool and an appropriate vessel for student evaluation, multimodal projects have yet to achieve this same clout. Therefore, students may approach the challenges of a digital project with apprehension regarding its usefulness or relevance to their humanities education.

We believe that these fears may be overcome by providing students with hands-on instruction to ensure that they possess the ability skills to purposefully navigate through, and successfully create with, these platforms. This necessitates that class time and instructor attention must be devoted to teaching the technical side of working within digital media. We hope that the video tutorials we have developed to provide step-by-step guides to key aspects of WordPress can be used by others to enable students in the digital humanities classroom to utilize WordPress with confidence. One other strategy is to provide students with models of digital projects prepared by students in past courses. Being able to explore different projects allows students to see what is possible, and concretizes the different set of expectations between a print essay and a digital project.

Additionally, given the initial challenges that working in a digital environment presents for many students, it is important that proponents of this type of assessment clearly illustrate what can be done “with digital media that we [can] not do otherwise” (Kuhn, Johnson, and Lopez 1). In their article and interview series “Speaking with Students,” Kuhn, Johnson, and Lopez identify some of the value-added learning experiences of born-digital work, including acquiring the skills of “advanced digital literacy”; “deploying the registers of text, image and interactivity”; and creating a space to actively engage an academic audience in “unprecedented ways” (1). By showcasing the unique value of digital scholarship, a niche can be created for this type of work as an acceptable humanities assessment. We have tried to exhibit these valuable learning opportunities by creating video tutorials that help teach students how to work with both text and media, and by creating a space that showcases past projects, visualizing the possibilities of a digital project and encouraging future students to engage in these scholarly conversations.

Another challenge is learning to integrate media and hyperlinks in a purposeful and meaningful way. During the course of creating our digital projects for the 2014 semestercourse, we were encouraged to provide embedded images and hyperlinks in order to embrace the multimodal advantages of a digital space. So too does one of the video tutorials created for the 2015 course strive to equip students with the tools to hyperlink and embed images, video, and audio so that the student projects can successfully interact with other digital platforms. Yet while it may be easy to think that connecting different sources of information to one another (as a website may hyperlink to another related website) is an interactive act, Lev Manovich emphasizes that interactivity is deeper: true interactivity is a psychological or mental process (71). In “The Myth of Interactivity” (from The Language of New Media), he argues that “the concept of interactivity” as used with regard to digital media “is a tautology” (71). As he says, “Once an object is represented in a computer, it automatically becomes interactive” (71). Thus, while instructors may encourage students to hyperlink and embed, it is important for us to be guided to do so with careful consideration and intent. Instructors should ensure that students are made aware that hyperlinks and embedded images may connect their site to other sites, but that this act does not guarantee that their digital project will be intellectually stimulating. If the hyperlink or embedded image is not a key source or component of the project’s main idea or argument, or if it does not help to guide, develop, or build the project’s idea or argument, then the hyperlink or embedded image is probably unnecessary.

AM and LS: Because WordPress is designed as a personal blogging platform, many of its features and its fundamental structure are not conducive to building a digital literary project. Unfortunately, at this time, there are no open source digital edition builders available, so students must learn to work within the limitations of this program or one like it. One potential problem for students is that the free version of WordPress does not provide any plugins for annotations. If students are inclined to build a text-based edition, being unable to efficiently markup the text is a serious limitation. Digitizing Literature ran into this problem and navigated around it by embedding site-internal hyperlinks, but this solution is less than ideal.

Additionally, WordPress lacks the coded search capability of a custom TEI-XML site. This means that while the WordPress search engine can identify the words displayed on each webpage, it is unable to access information that could be embedded in humanistic markup. For example, if TEI-XML were used to encode place names or person names in a document then a site user, who was interested in this type of information, would be able to call up all the encoded instances instead of having to search individually for each proper name. This type of categorical searching opens up an entirely new way of accessing or using the text at hand. Furthermore, as TEI-XML is a discipline standard in the humanities, this incompatibility is a significant loss, though WordPress’s ease of use makes it an acceptable trade-off, at least when working with undergraduate students.

ML, AM, LS: Evaluation of students’ digital projects presents challenges, both from the instructor’s and the students’ point of view. The expectation of most students at this later stage in their academic career is that a research essay will be graded based on: the competence of their research; the soundness and originality of their argumentation; the persuasiveness of their close reading; and the clarity and elegance of their writing. With a digital project, all of these components persist as requirements, but with the additional burden of students being asked to translateing their research into (what will likely be) a new digital medium. In essence, students are being asked to use a new language to present their research and writing, and this can cause anxiety on the part of students and the instructor, who rightly may be concerned that they are demanding too much. Many students have worked for years to craft arguments for and present textual evidence on the printed page; therefore, transitioning the print-based essay into digital form requires thought and planning. Further, students may find basic tasks, such as editing and proofreading, more difficult within a digital environment. For all of these reasons, assessment provides a new set of challenges problems to the instructor, who wishes to encourage experimentation and creativity while at the same time maintaining high standards for argumentation, analysis, and composition. One way to address this problem is by providing students with explicit grading rubrics, and staging feedback throughout the course through peer review and both formative and summative assessment (the former providing feedback to students while they are still working on their projects, and the later provided after they have completed and submitted the project). Example materials for these various forms of feedback are available on our companion site.

Although many issues were resolved by the second iteration of the course, some remain. In particular, argumentation that spans many web pages can be difficult to sustain. Students have been encouraged to include introductions and conclusions that state and restate their overarching claims, but a digital project seems tomay require a different style of argumentation. Further, students use images and moving pictures far more than in print-based essays, and literature students must therefore develop analytical skills appropriate to those visual media. Of course, the inclusion of images and video often raise issues of copyright and proper citation. One strategy used in the second iteration of the course was to require students to include a works cited for images, but thorny issues, such as whether students can take screenshots and otherwise use images from other resources, persist.

Best Practices

ML, AM, LS: In the list of best practices that follows, we offer a series of suggestions that address many of the pedagogical challenges we have identified. Our main recommendations are (1) that the students be given explicit guidance, throughout the course, in how to construct a digital project, through the use of hands-on workshops and video tutorials, the provision of written documentation, and the presentation of previous student projects as models; (2) that the course assignments be understood cumulatively, such that students are encouraged to re-use material from previous assignments in the final project; and (3) that the timeline for producing the digital project be staged over the course of several weeks.

The following table discusses a series of pedagogical interventions over the course of the term, to help guide students through the development of the project. Links are provided to our web-based tutorial guides and course material.

|

Stage within Course |

Pedagogical Intervention |

Links |

|

Early |

Proactive Instruction in Digital Technology: Students should be given an introduction to WordPress (or other digital platform), with terminology and a practical guide to demystify it. A formal tutorial early in the semester describing the technical particulars avoids the assumption that all students are digitally savvy. |

Video Tutorials: Creating a WordPress Site; Creating a Page; Adjusting Theme & Customizing; Final Project Technical Guidelines |

|

Models of Digital Projects: Students should be shown models of digital projects prepared by students in other courses to gain a better sense of possible projects. |

||

|

Middle |

Cumulative Design of Course Assignments: Given the steep learning curve, students are encouraged to integrate their earlier assignments (in this course, a traditional print essay, due about a third of the way through class), into the final project. |

|

|

Digital Coaching: As they begin to conceptualize their project, students must be given instruction in best practices in site design, and for incorporating multimedia and hyperlinks. The Final Project Proposal encourages them to begin to think through these issues by requiring a diagram of their site and a discussion of other design and organizational elements |

Video Tutorials: Integrating Media & Hyperlinks ; Digital Site Design |

|

|

Formative Assessment: Students should be asked to prepare a final project proposal for feedback and evaluation. In this proposal, students should be asked to think about their research question, methodology, and how they will design their website to best represent their argument/evidence. As part of their proposals, students are asked to diagram the design of their project site for feedback, or to provide an URL to a shell site that can be viewed for feedback. |

||

|

Late |

Peer Review: Given that students may not be prepared for the challenges of revising and proofreading a digital assignment, and will almost certainly produce more text than they do in print-based assignments, time should be allotted for peer review. Peer review can be conducted in class and/or digitally. |

|

|

Evaluation Rubric: Students should be provided with a detailed rubric of assessment for their digital project. As this project may take many different forms, it is important that general principles and expectations be enunciated and quantified. |

Conclusion

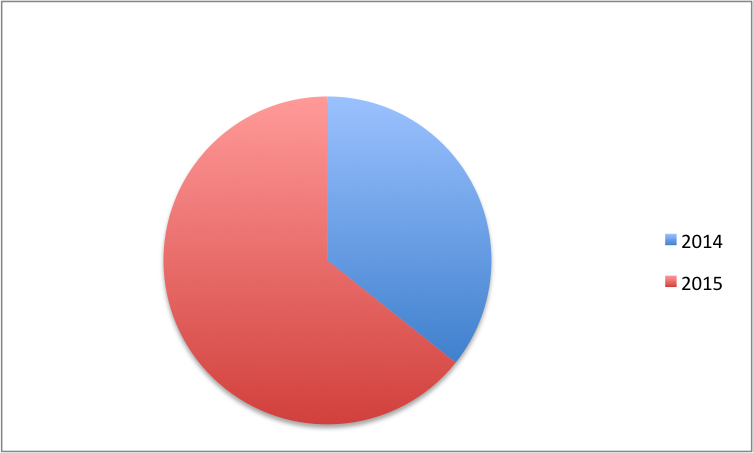

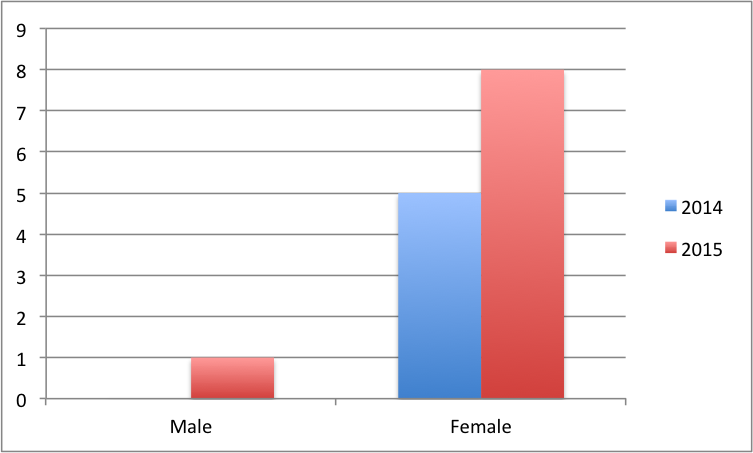

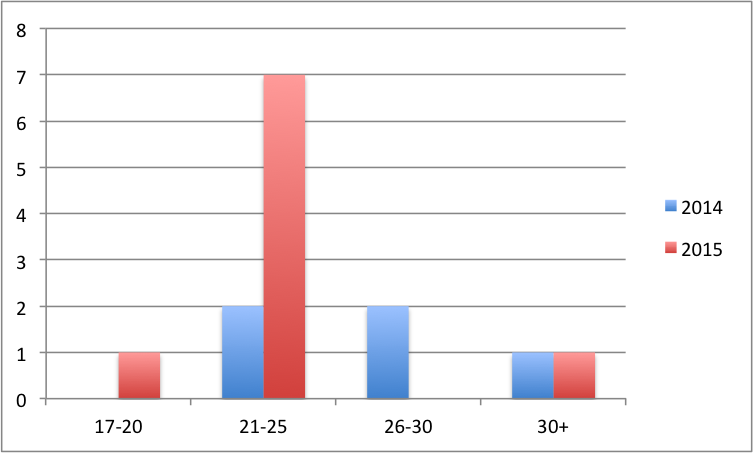

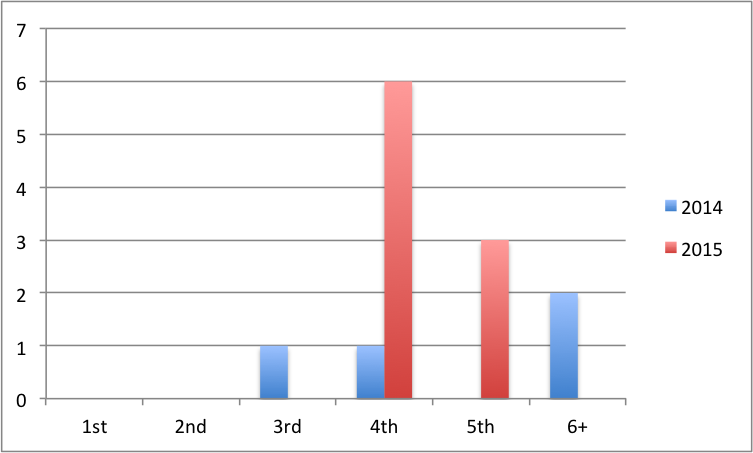

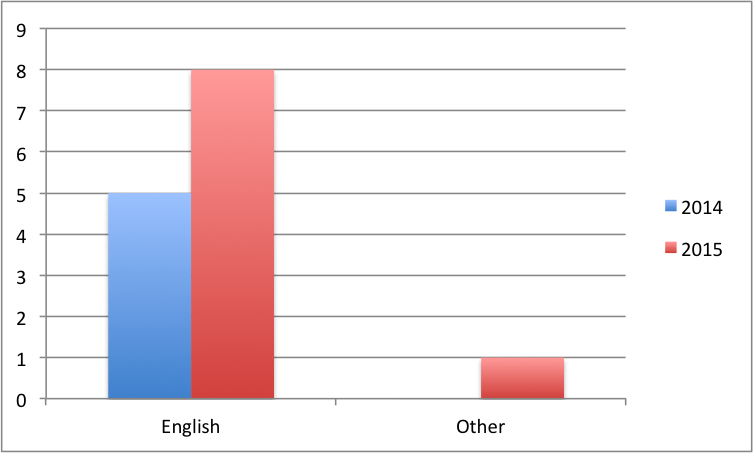

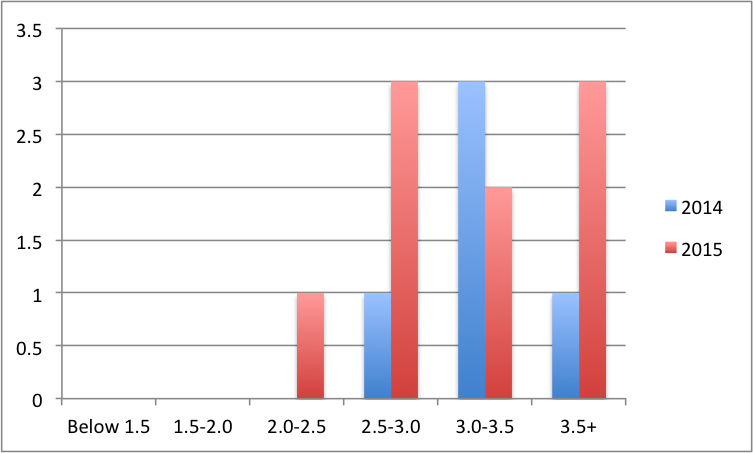

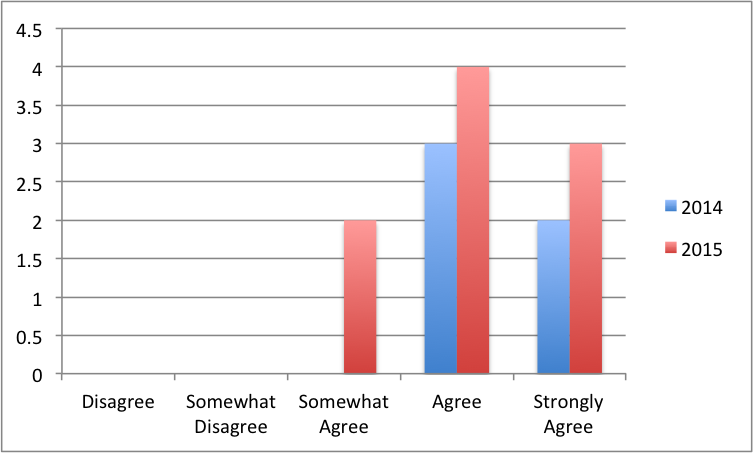

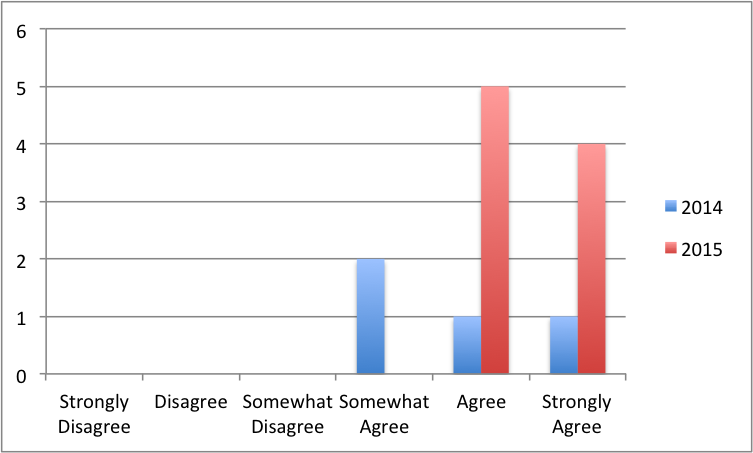

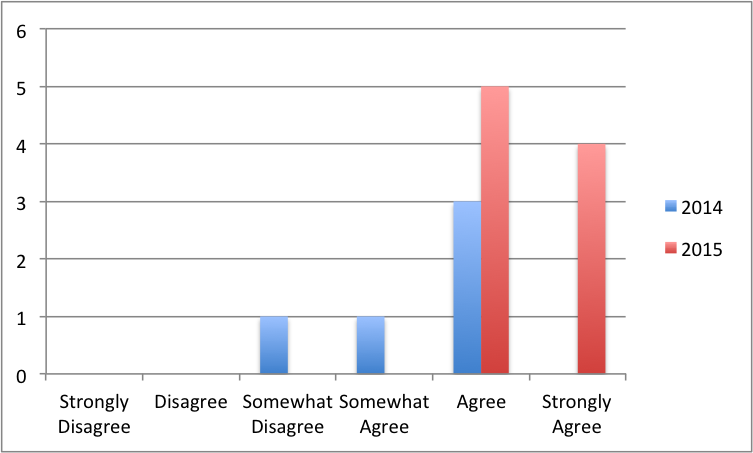

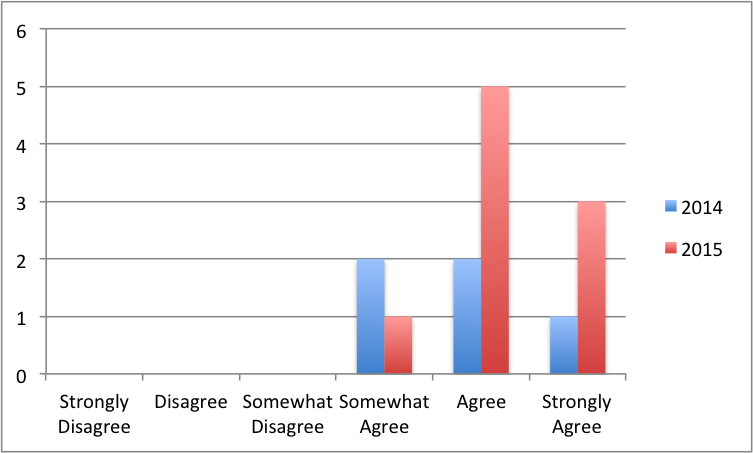

We would like to concluding by reporting on results of student evaluations of the course. The students in both the 2014 and 2015 iterations of the course were asked to complete an anonymous online survey following the conclusion of the course this summerin the fall of 2015. The purpose of the survey was to determine how the students found the course material and structure, specifically the integration of technology through assignments and evaluations.

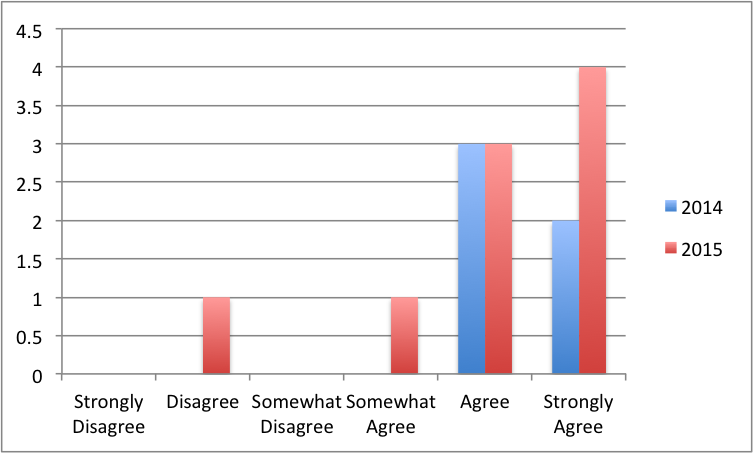

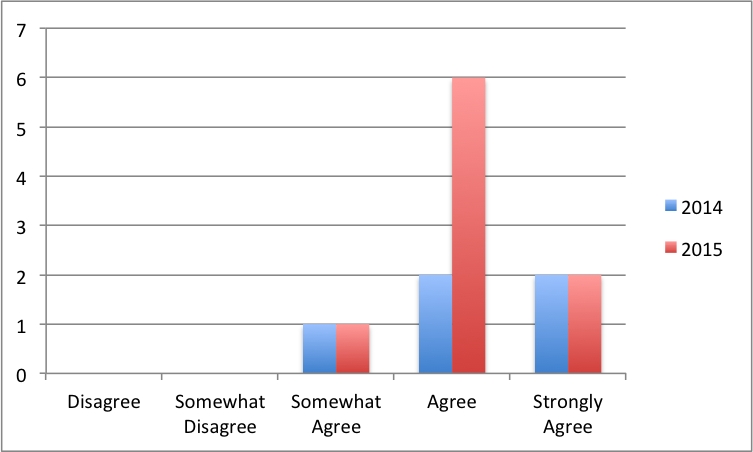

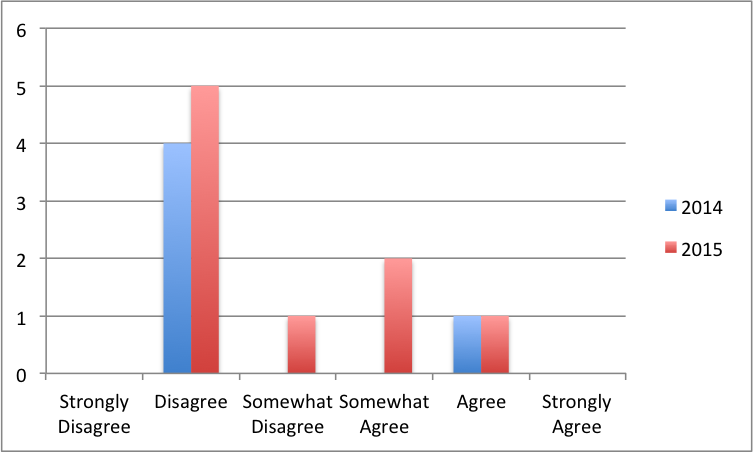

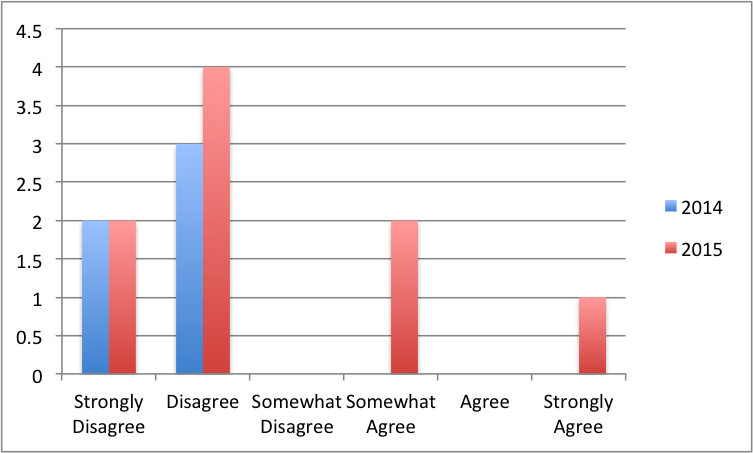

Fourteen students completed the survey: five from the inaugural class of 2014 and nine from the second iteration in 2015. While three of the students originally hesitated in registering for the course because of the digital element, all of the students enjoyed learning to use the digital tools and agreed that they were helpful for studying English (Q.13, Q.9, Q.10).

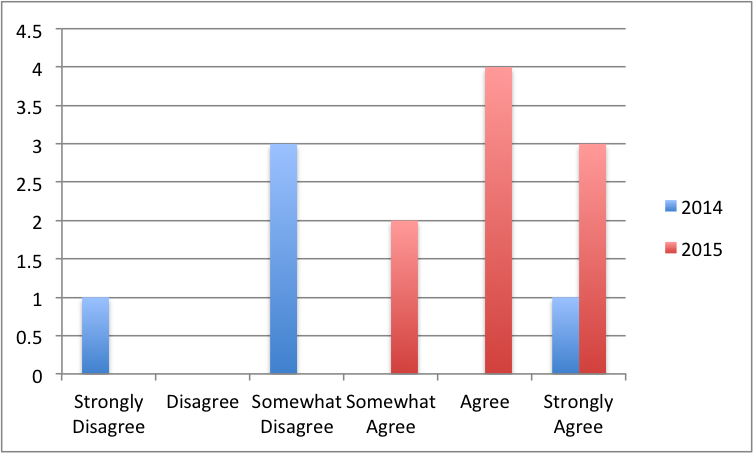

Overall, the students felt that their technological skills improved over the duration of the course; the students also felt more confident in their use of WordPress at the course’s culmination (Q.15, Q.16). On average, the students in the 2014 class felt less confident in the explanation of digital tools than the 2015 class: of the five students in the 2014 class, three answered this statement with “agreed”, one with “somewhat agreed”, and one with “somewhat disagreed.” By comparison, the 2015 students answered either “strongly agreed” or “agreed” (Q.17).

As these survey results suggest, the exploration and suggestions made in this paper are not only based on pedagogy theory and our reflections, but also on participant evaluations. The changes made to the course had a positive impact on the students’ confidence in both using digital tools and in their mastery of WordPress as a content management system. The resounding agreement that the digital tools provided meaningful strategies for understanding were a useful window into English literature both supports our objective for this course and bolsters our argument for the importance of integrating humanistic research with technological innovation.

Works Cited

Branscum, John and Aaron Toscano. “Experimenting with Multimodality.” Mulitmodal Composition: Resources for Teachers, edited by Cynthia L. Selfe, Hampton P, 2007, pp. 83-98.

Appendix A: Student Survey

Question 1: What course did you take?

- English 427W Summer 2014

- English 427W Summer 2015

Question 2: What is your gender?

- Male

- Female

- Write in preferred gender term

- Prefer not to say

Question 3: What is your age?

- 17–20

- 21-25

- 26-30

- 30+

Question 4: What year of university are you in?

- 1st

- 2nd

- 3rd

- 4th

- 5th

- 6th+

Question 5: If your major English?

- Yes

- No

Question 6: If your major is not English please specify what it is.

Answers not included to protect student privacy

Question 7: What is your cumulative grade point average?

- 3.5+

- 3.0-3.5

- 2.5-3.0

- 2.0-2.5

- 1.5-2.0

- Below 1.5

Question 8: I enjoyed the use of digital tools in this course.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

Question 9: I found diital tools useful in studying English

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

Question 10: I would prefer to use a platform other than WordPress

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

Question 11: If you would prefer to use a platform other than WordPress, please include the name of this platform below.

Answers not included to protect student privacy

Question 12: I hesitated in taking this course because of its digital element.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

Question 13: If you had concerns about the digital element before taking this course, please explain what they were.

Answers not included to protect student privacy

Question 14: Before entering this course I felt confident with the digital tools we used.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

Question 15: After finishing this course I felt confident with the digital tools we used.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

Question 16: I felt that the digital tools we used were adequately explained.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

Question 17: If you disagreed with the question above please explain what components required greater explanation.

Answers not included to protect student privacy

Question 18: I was supported in my use of digital tools.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree

Question 19: I enjoyed the cumulative nature of the assignments.

- Strongly agree

- Agree

- Somewhat agree

- Somewhat disagree

- Disagree

- Strongly disagree