Recent Thelwallian conversations have grown from and reflected back upon the essays in John Thelwall: Radical Romantic and Acquitted Felon.

Conversational exchange was congenial to Thelwall himself, as the medium of “philosophic amity” he anticipated at the end of his West Country tour in summer 1797 (Retirement 129). Both Robin Jarvis and Michael Scrivener have shown how Thelwall’s “Pedestrian Excursion through Several Parts of England and Wales during the Summer of 1797” expressed an “intellectual mobility” that combined remarks on picturesque beauty with “the social labor and political conflicts that also are part of the land’s meaning” (Scrivener 224). The “Pedestrian Excursion” and its postscript “The Phenomena of the Wye, During the Winter of 1797-8” are exemplary instances of what Scrivener terms the “social creativity” of Jacobin writing (295), a creativity also manifest in what Judith Thompson has noted as the democratic temper of Thelwall’s experiments with form and genre in The Peripatetic (11, 18, 29).

“The Phenomena of the Wye” records a late stage of Thelwall’s west country excursion. It was published in the Monthly Magazine for May and July 1798, before the other instalments of the “Pedestrian Excursion” appeared between 1799 and 1801. This arrangement is peculiar. Perhaps Thelwall intended it to distract attention from the missing segment of his excursion—what occurred between Thelwall setting-off from Bath with “solitary step” (“Pedestrian” 55) and his arrival in the middle of the autumn at the Wye Valley on his “first visit to [those] parts” (“Wye” 5). If that was indeed the design, it didn’t work. The missing section of the tour was in fact its principal purpose, as announced by Thelwall in his prefatory remarks: a visit to his “invaluable friend” Samuel Taylor Coleridge at Nether Stowey (“Pedestrian” 17).

As reconstructed without reference to the “Pedestrian Excursion” the visit to Stowey has been seen to mark Thelwall’s retreat from metropolitan radicalism and ‘“the vortex of public contention” to become the “new Recluse” of Liswyn Farm, and, later, a Lecturer on Elocution (Retirement xxiii, xxxviii).

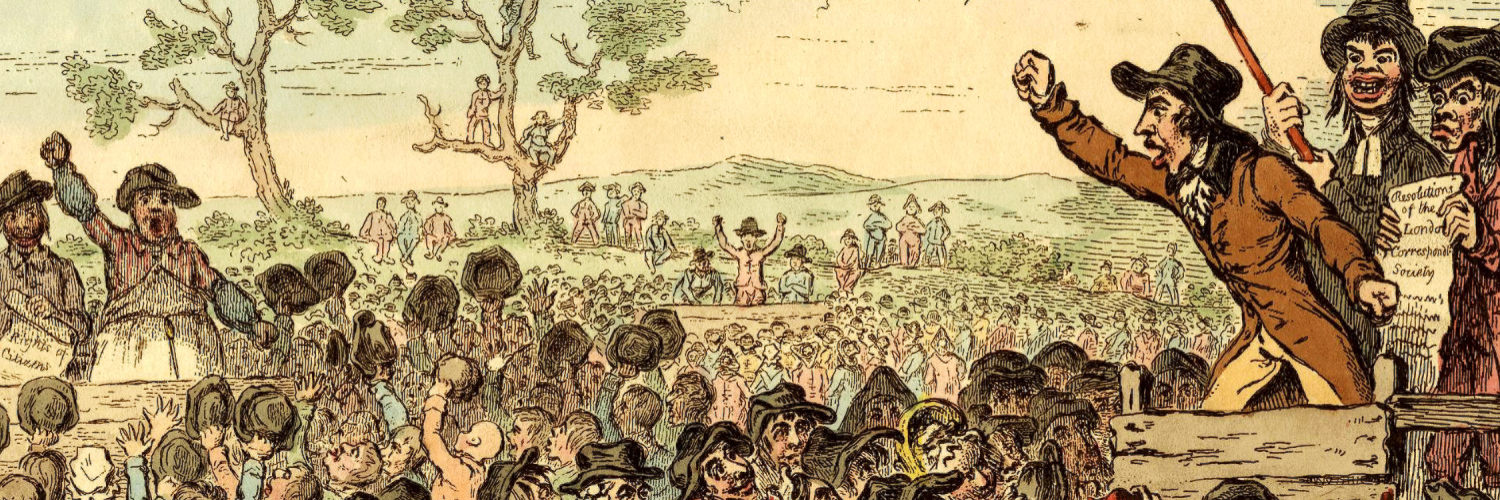

That “turn” might summarise Thelwall’s trajectory from London in 1795 through to Liswyn in 1801, a trajectory impelled negatively by persecution, disappointment, and marginalisation and positively by the wish for friendship, correspondence, and affection. The subsequent lapse of “philosophic amity” leads to “retreat,” “retirement,” and “reinvention,” from which Thelwall re-emerges with a new identity as an elocutionist. Several essays in John Thelwall: Radical Romantic challenge this profile, by pointing to continuities between Thelwall’s political lectures and his practice as an elocutionist. Simply put, as a political lecturer in the 1790s, Thelwall was the voice of the inarticulate; in later years his elocution helped the tongue-tied to speak for themselves. As the popular orator of the Corresponding Society Thelwall had lisped and stammered at the tribune; Thelwall the speech therapist lectured on “Bonaparte and the Spanish Patriots” at the Angel Inn, Tiverton.

When in the mid-1790s the London Corresponding Society was forced underground it adopted the cover of the “School of Eloquence,” a school in which Thelwall—had he chosen to do so—might have continued his political lectures. He didn’t so choose. He set off first to East Anglia, and was rebuffed by riots. He then trekked north to Derby, to find the offer of a newspaper editorship had been foreclosed. With London in 1797 a no-go area for him, there was little option but to step westwards on a walking tour towards a correspondent, not as yet encountered in person, who appeared to promise all that Thelwall was denied elsewhere in England: familiarity, affection and intellectual fellowship.

In this article I want to offer some further arguments for a continuity between Thelwall up to the “Pedestrian Excursion” in 1797, and the Thelwall who re-emerged from Liswyn Farm. I want to attend to Thelwall and the sense of place, and to ask what it meant at that moment to step westwards in the hope of establishing “a more immediate and intimate communication” with friends settled in the West Country (“Pedestrian” 17). Within that narrative of continuity, I want also to speculate about the breaks and fractures signalled by the published version of Thelwall’s “Pedestrian Excursion.” As presented in the Monthly Magazine, the anticipated “communication” with his friend produces a dislocation in the “Excursion” narrative that prompted Thelwall to publish the “Phenomena of the Wye” first, and separately from, the “Excursion” it should have concluded. In this arrangement of the narrative, the episode of friendly communication with Coleridge is completely excised.

*

Thursday, 29 June 1797. Thelwall and his friend Wimpory set off from London between nine and ten o’clock in a heavy shower of rain. Their route will take them out of London to Windsor, Basingstoke, Andover, Salisbury, Amesbury, Stonehenge, Winterborne Stoke, Wylye, Fonthill, Wardour Castle, Mere, Frome, Bristol and Bath . . . and eventually to the Wye Valley. Broadly speaking Thelwall was following earlier travellers such as Thomas Gray and William Gilpin, and William Wordsworth on his 1793 venture westwards from London, via the Isle of Wight, Salisbury and the Plain, to Bath and Bristol. If we include Wordsworth’s wider poetic migrations between 1793 and 1798 we might say that Thelwall was tracking a topography of the imagination that led from the desolate vistas represented by an early poem like Salisbury Plain to the human landscapes of Lyrical Ballads. Thelwall, likewise, abandoned the persecutions of London and headed westward in the hope of human community, and for Thelwall, too, the westward journey would produce significant challenges and transformations.

The social, cultural and political observations that inform Thelwall’s “Pedestrian Excursion” have been widely noted, and comparisons have rightly been made with Arthur Young and William Cobbett.

More can I think be said, and one keynote is Thelwallian diversity. Thelwall is familiar to us as a journalist poet, orator, lecturer, leader of popular societies, speculative scientist, and elocutionist. He was also a published dramatist, pamphleteer, autobiographer, novelist, and diarist. His other identities include Thelwall the political agent, songwriter, editor, pedestrian, naturalist, farmer, and collector. To these we can add his early years in his father’s silk business; apprentice to a master-tailor; epic poet; trainee lawyer; aspirant actor, and would-be historical painter. I wrote in “The Lives of John Thelwall” about his various identities as a “private citizen,” “Citizen Thelwall,” “Brother Thelwall,” Sylvanus Theophrastus, John Beaufort, “the new Recluse,” “Citizen John,” “Citizen Jack,” “the famous Thelwall,” and “the lisping orator.” And I suggested that it is possible to map a comparable diversity in other areas of Thelwall’s life—for example in his travels and tours throughout England. It’s worth emphasising these earlier selves, because we overhear many of their voices in the course of his “Pedestrian Excursion.”

Who are they? A non-exhaustive list, arranged alphabetically, includes the following Thelwalls, all of whom we hear from in the course of the “Excursion”:

- Thelwall the Agriculturalist, concerned with crops, farm and land maintenance, and the condition of the soil.

- Thelwall the Antiquarian, who is intrigued by the mutilated wooden monument at Salisbury Cathedral, and speculates on the astronomical function of Stonehenge (“Pedestrian” 29, 37).

- Thelwall the Art Historian, who appears throughout the “Excursion,” comments on the chapel paintings at Amesbury House and finds occasion to remark on contemporary painters such as West, Barry, Northcote and Fuseli (34-36).

- Thelwall the Architect, ready with an opinion on “the fine florid Normo-Gothic style” of St. Mary Redcliffe at Bristol, the interior of Salisbury Cathedral and “[t]he many-shafted pillars and Saracenic (or Normo-Gothic) arches that divide the nave and circles . . . handsome, uniform and in excellent proportion” (53, 28).

- Thelwall the Classical Historian “nurtured with the love of Roman liberty,” whose appreciation of Roman busts, coloured by his knowledge of the times, gives us “the bloated, intemperate, licentious, effeminate, mischief-meditating countenance of Nero, with his pursed-up, pouting, distorted mouth, and assassin arm wrapped up in his cloak” (31).

- Thelwall the “confidential correspondent” of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (17).

- Thelwall the Economist prepared to expatiate on “National Debt,” “Circulating Medium,” “Waste Lands,” and the rural wages of labourers (“Wye” 10-12).

- Farmer Thelwall, as concerned as the agriculturalist about “the state, cultivation, and the fertility of pastures,” drainage, the size of farms and the condition of farm buildings (“Pedestrian” 22).

- Thelwall the Gallant, with an eye to the “mistress of the house” who is “somewhat handsome” (24-25).

- Thelwall the Industrialist, whose childhood experiences inform his remarks about the silk-mill near Basingstoke, and the cloth mill at Frome (26-27, 48-49).

- Thelwall the Journalist—the published text of the “Excursion” is a gleaning from his more extensive “observations” (17).

- Then there is Thelwall the Landscape Painter and Gardener, ready with comments on Poussin, Claude, and the layout of Windsor Great Park (“Wye” 3; “Pedestrian” 21).

- Thelwall the Pedestrian, the Peripatetic, and the Picturesque Traveller.

- Thelwall the Politician who remarks briefly on liberty and justice and resists an “elaborate dissertation” (“Pedestrian” 32).

- Thelwall the Public Figure or “Celebrity” who is recognised at Frome and suddenly and unexpectedly finds himself “in the midst of friends” (48).

- Thelwall the Utopian Thinker, who “formed Utopian plans of retirement and colonisations” (21).

- And finally, to round up this list, there is Thelwall the Bon Viveur on the watch for his next meal: bread and milk (20); tea and rolls and cream (21); eggs, bacon, and ale (25); new milk (26); “animal food” (27); ham, eggs, salad, gooseberry pies and ale (41-42); a cold leg of lamb, lamb chops and salad (46). All of this country fare is sampled en route to Stowey.

So Thelwall assumes diverse identities and discourses, adapts himself to occasion, and, except for the moment when he is recognised at Frome, travels across country incognito. And we hear accordingly little of what Thelwall felt in himself—the “Excursion” concerns itself with the physical, material detail of landscapes, buildings and contents, soil, wages, the condition of rivers, the cleanliness or otherwise of inns, and the palatability of food. When we part company from him at Bath, he is headed further west into Somerset, to meet his confidential correspondent “well known in the literary world” (17). We shall meet Thelwall again as the different creature of the “Phenomena of the Wye” articles, and as Thelwall himself leaves a gap in his narrative I am going to take this opportunity to offer a few conjectures about what it meant to step westward to Nether Stowey in summer 1797.

Thelwall’s “eccentric ramble” westwards was exactly that: a trajectory outwards from the city towards a location off-centre, away from the uproar of public life towards a “more immediate and intimate communication” with a private friend (“Pedestrian” 17). The Quantock Hills, two days from London by the fastest coach, offered the geographical and psychological sense of remove and reassurance that had already attracted Coleridge from Bristol and, more recently, Wordsworth and his sister from London via Dorset. Here, as Richard Holmes’s biography of Coleridge showed us, were the provincial landscape and culture that inspired Coleridge’s early visions.

One question occurs. Why the Quantocks? Wouldn’t another region of England, Wales or Scotland have served as well? At a period of political and social unrest the Quantocks might be thought to have offered shelter from political persecution such as Thelwall had endured, and the shaded coombs and windswept uplands both nurtured and disciplined literary composition. This is the landscape Coleridge celebrates in Fears in Solitude and yet, rather than offering a remove from the centre of unrest in London, Somerset was the historical heartland of rebellion—as Coleridge, a Devonshire man, certainly knew. A dozen miles from Nether Stowey was Taunton, a parliamentary stronghold during the Civil War and an important centre for Non-conformity with an academy (c. 1670-1759) linked to the network of dissent that criss-crossed the country. The Duke of Monmouth’s challenge for the throne in 1685 had gathered momentum in Dorset, only to meet defeat at “sad Sedge-Moor”—Thomas Hardy’s phrase (line 8). Hundreds were executed in Judge Jeffreys’s “bloody assizes” that followed. When the French planned an invasion attempt in 1797, they targeted a remote area of the Somerset coast close to Coleridge’s home at Nether Stowey. Was this fortuitous? A matter of wind and tide? Or did the French anticipate a welcome from locals whose forebears had experienced murderous retribution? Certainly Coleridge and Wordsworth found a like-minded friend in Thomas Poole, the tanner of Nether Stowey who had founded a poor man’s club in the village (Poole’s enemies thought of the club as a private army over which he had “intire command”).

For Thelwall, the excursion to Somerset was less an escape from the dangers of London than a homecoming in a provincial landscape long associated with resistance—a resistance that in the days of King Alfred had arguably led to the foundation of England itself. The geopolitical history of the West Country was unquestionably a factor in the Home Office decision to dispatch the spy—Coleridge’s “Spy Nosy”—to report on “the famous Thelwall” and the “nest of democrats” at Alfoxden, and we can see those associations continued in the next generation. Ten years later, in 1808, Leigh Hunt’s friend J. P. Marriott founded the Taunton Courier—a liberal newspaper, modelled on Hunt’s London Examiner, that circulated throughout the West Country. On the first page of the first issue, 22 October 1808, the Taunton Courier carried an advertisement for Thelwall’s forthcoming lecture on “Bonaparte and the Spanish patriots” at the Angel Inn, Tiverton. Hunt’s brother John, publisher of the Examiner, actually made his home in 1819 a few miles from Taunton at Cheddon Fitzpaine: it was a settlement long postponed, for the Hunt brothers were descendants of an ancient Devonshire family from South Molton. The assertive political-cultural independence of The Examiner in which Shelley and Keats found their first readers was a West Country inheritance, and that inheritance is arguably why Thelwall, Coleridge and Wordsworth had also relocated from London to the Quantocks at a moment of political crisis and impending repression in the mid-1790s. Often thought of in terms of “retreat,” “retirement,” and “disengagement,” the road to Nether Stowey was taken by those, like Thelwall, who sought continuity, confidentiality, and communication at a time of “default” in the centre. Thelwall’s “eccentricity” signalled his refusal to abandon the cause: his wayward trajectory to the west was a homing-in on the one area of the country likely to prove receptive to his democratic campaign. If that was indeed his expectation, the experience proved somewhat different from what he had anticipated—hence the fracture in the published narrative of the “Excursion.”

Thelwall’s “familiar and confidential correspondence” with Coleridge was the conversation of t wo friends whose political ideals overlay intractable differences. Thelwall was a materialist, as his Essay on Animal Vitality and the “Pedestrian Excursion” demonstrated. The Essay argued that spirit “must be material,” possibly the mysterious “electrical fluid” that was simultaneously “a fine and subtle, or aeriform essence” that is “superadded to matter” (116-17). In the “Excursion” Thelwall’s concern is “observations”—social, topographical, picturesque, architectural, economic, agricultural, gastronomic. Indeed, apart from the state of his stomach, we hear almost nothing about Thelwall himself—no impressions, no hint of personal feelings, no imaginative response. As a single suggestion of what might have been possible, Wordsworth evidently heard about or looked over Thelwall’s journal and noted his observation of how “tasteless inhabitants . . . have daubed their houses, and one in particular, the very colonnade before his door, with green paint” (“Pedestrian” 19). “Tintern Abbey” removes all inhabitants from the scene, and restores a natural continuity between the landscape and “pastoral farms / Green to the very door.” Thelwall is concerned with taste, or its lack, as materialised by “the country houses of persons long immured in large cities” (20). Wordsworth’s more impressionistic vision tells us of his wish to see a landscape in which human presences almost pass unnoticed.

At Stowey Thelwall, Coleridge, and the Wordsworths talked, walked, dined, and recited poems and plays, and as David Fairer has recently argued, it rapidly became clear that Thelwall’s materialism was at odds with Coleridge’s idealism and spirituality. That apparent conflict did not preclude some interassimilation, as I suggested in tracing “Tintern Abbey”’s conversation with Thelwall’s “Lecture on Animal Vitality” (Politics of Nature 93-95). Thelwall, likewise, obliged to quit Nether Stowey, was aware of Coleridge’s experiments with landscapes of feeling in his recent poem “This Lime-Tree Bower my Prison.” That awareness is apparent in Thelwall’s own blank verse poems, “Lines Written at Bridgewater” and “To the Infant Hampden,” and also in “The Phenomena of the Wye, during the Winter of 1797-8” to which I now want to turn by way of concluding.

There are some continuities between the narrative of the “Pedestrian Excursion” that in chronological terms preceded the “The Phenomena of the Wye” but, as indicated already, saw print rather later. As apparent are some notable differences. In particular, “The Phenomena of the Wye” shows us Thelwall moving towards a more subjective, mediated vision that discovers emblems or symbols of his own feelings in the landscape. The “eccentric ramble” of Thelwall’s recent past greets the “intricate meanders” of the Wye in a moment of self-recognition that is also an acknowledgement of survival amid “eternal diversity” (“Wye” 4). If we do not hear the thoughts and feelings of the “pensive wanderer” who saunters along the banks, the sight of “successive strata of sand, of gravel, and of rock” glimpsed through the “transparent stream” is suggestive of depth and retrospection (as in Coleridge’s sonnet “To the River Otter”) (4). Thelwall the materialist is now prepared to grant that a scene may be “enchanting” and may result in “curiosity inflamed”; the atmosphere can be “thick,” and a sky “sullen” (3). Here are “mingled impressions” (4), a “transparent veil” (7), “rays of sun tingling with transient glow” (6), and “a sort of wild and awful music” reminiscent of the poems of Ossian (8). Thelwall was on the way to realising how the language and rhythms of poetry offered the release, the response, and the “intimate communication” he had sought in making his “Excursion” to meet Coleridge at Stowey (“Pedestrian” 17). As he tapped into his own experiences and feelings in the post-Nether Stowey Poems Written in Retirement of 1801, Thelwall was already alert to poetry’s potential to liberate those whose speech was as fractured as his own. Thelwall’s “road to Nether Stowey” led beyond the village limits, to the Wye, to Liswyn, and, ultimately, to his Institute of Elocution at Lincoln’s Inn Fields.