Almost two centuries after his death, the Romantic-period political reformer John Thelwall is undergoing a remarkable critical renaissance. In the past five years alone he has been the subject of three conferences, a four-volume selected writings, an inaugural collection of essays, diverse articles and chapters, a dramatic premiere, a special issue of the journal Romanticism, and a campaign to restore his grave.

In the recent opinion of one scholar, Michael Scrivener, “a strong argument can be made that one does not understand Romanticism in sufficient depth if one has not engaged seriously the oeuvre of Thelwall” (Rev. of Peripatetic). The discovery in 2004 of a three-volume faircopy of Thelwall’s poetry that includes several previously unknown compositions, notably a satire on the leading poets of the day, makes only the most recent addition to that strikingly diverse oeuvre.

A quintessential Romantic polymath, Thelwall also composed political lectures and pamphlets; a controversial essay on the principle of life; five collections of poetry;

three anti-imperialist plays; an abolitionist, feminist novel; a novelistic miscellany in verse and prose; periodical essays and reviews; and copious writings on elocution and speech therapy.

That these works have gone largely unremarked for so long is owing partly to their rarity, and partly to their author’s “radical” stigma. Along with Thomas Hardy and John Horne Tooke, Thelwall was a key defendant at the Treason Trials of 1794, when the Pitt government attempted to suppress the radical reform movement by depriving it of its leaders—and its leaders of their heads. (The penalty for “compassing” and “imagining” the king’s death was hanging.)

Although the prosecution’s claims that the defendants had been conspiring to depose the king and establish a French-style republic would not stick, the “acquitted felon” label stayed with them for life

(for a time, however, friends like Coleridge preferred to think of Thelwall as a “virtuous High-Treasonist” [Letters 1: 259]).

With the exception of Charles Cestre’s 1906 study, John Thelwall: A Pioneer of Democracy and Social Reform in England during the French Revolution, based partly on six manuscript volumes purchased at auction in 1904 and now lost,

Thelwall was largely relegated to the footnotes of history until the mid-twentieth century, when he emerged as a hero of the British left in E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963). Since then, he has become a recurrent figure in studies of late eighteenth-century political culture. Singling him out as the foremost republican writer in Britain after Paine’s flight to France in 1792, Gregory Claeys argues in The Politics of English Jacobinism: Writings of John Thelwall (1995) that Thelwall’s adaptation of the Lockean natural rights tradition in response to widespread poverty resulted in a “new vision of economic justice” that laid a foundation for the development of socialist and liberal thought in the nineteenth century (liii).

Meanwhile, Thelwall’s equally innovative and prolific literary and elocutionary works have attracted increasing attention since the publication in 2001 of both Michael Scrivener’s Seditious Allegories: John Thelwall and Jacobin Writings and Judith Thompson’s edition of Thelwall’s verse-and-prose work The Peripatetic of 1793. In the intervening decade, scholars have begun to challenge earlier dismissals of Thelwall as a “mediocre poet” (Thompson, Making 172) and a prosodist-elocutionist who would have been “none the worse of a hanging” (Saintsbury 157). The most recent additions to a growing body of Thelwall scholarship include Incle and Yarico and The Incas: Two Plays by John Thelwall (2006), edited by Scrivener and Frank Felsenstein; the four-volume Selected Political Writings of John Thelwall (2009), edited by Corinna Wagner and Robert Lamb; and the collection John Thelwall: Radical Romantic and Acquitted Felon (2009), edited by Steve Poole. The latter grew out of two Thelwall conferences held in 2007 to mark the end of a successful campaign to restore his weathered gravestone in Bath, where he died of “some affection of the heart” while on an elocutionary lecture-tour in February 1834, age sixty-nine (“Mr. Thelwall”).

Like the gravestone, Thelwall’s oeuvre stands in need of further attention. Indeed, we are only just beginning to appreciate the diversity, originality, and coherence of a career that spanned four decades and brought Thelwall into contact with the leading Romantic writers, artists, thinkers, and activists. E. P. Thompson accurately remarked that Thelwall “straddled the world of Wordsworth and of Coleridge, and the world of the Spitalfields weavers” (Making 172). A leading representative of “romantic sociability,”

Thelwall also belonged to overlapping Romantic circles centred variously around Godwin and Holcroft; the radical publishers Daniel Isaac Eaton and Richard Phillips; the democrat-physicians Henry Cline, Astley Cooper, and Peter Crompton; the Norwich intellectuals William Taylor, Anne and Annabella Plumptre, and John and Amelia Opie; the Derby Philosophical Society members Erasmus Darwin and William and Joseph Strutt; the Westminster reformers Francis Place, Francis Burdett, John Hobhouse, and John Cartwright; and other figures including “the disputation metaphysical Hazlet [sic],” “poor Gilly” [Gilbert] Wakefield, Robert Southey, Charles Lamb, Thomas Noon Talfourd, and Henry Crabb Robinson.

Yet Thelwall’s practice is not in the end strictly comparable to any of theirs. He drew self-consciously on all the major traditions and discourses of the day to create a body of work as “radical” and heterogeneous as the conjunction of political, medical, and cultural discourses that informed it. If, as Thelwall maintained, “style is the shadow of mind” (Peripatetic 71), it is notable that his was consistently humane and democratizing, even when repression forced him to take a vow of “inviolable silence” on political issues (Retirement xxxvi).

The range of Thelwall’s interests and the scope for new archival discoveries are manifest in a “find” I made in the National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum, just as I was completing the editing of this collection: a copy of George Wilkins’s play The Miseries of Inforst Marriage (1629), owned and annotated by Thelwall.

The play may have been part of the large library that Thelwall amassed on the success of his career as an elocutionist in the early nineteenth century, the contents of which were sold at auction in 1820, as detailed in Patty O’Boyle’s essay in this collection. In addition to underlining and marginal scoring, Thelwall’s copy of the play bears two evaluative notes. The first, written on the flyleaf and signed “J. T.” (with “John Thelwall” added by a different hand), praises the “witty foolery” of the first scene, “which reminds us so strongly of the characteristic humour of Shakespeare’s Clowns,” and regrets that later scenes fall short of this standard; the second note, written on the back of the last page, remarks that it was “miserable want of judgment in the author” not to give the play a “tragical catastrophe.” The volume thus adds to the growing body of Thelwall annotations and inscriptions—including those on Bowles’s Sonnets, Coleridge’s Biographia Literaria, and Wordworth’s Excursion—that candidly supplement what we already know of his professional and personal opinions. The volume also suggests how Thelwall was remembered in the later nineteenth century. A note by Alexander Dyce (1798-1869), the literary scholar who bequeathed the play and thousands more works to the South Kensington Museum, identifies its previous owner as “John Thelwall,—a person of some talents in literature, & of great notoriety in consequence of his having been tried for high treason.”

Capitalizing on this conjunction of new material and renewed critical momentum, the present volume aims to help restore Thelwall to his rightful place in history and Romantic studies by publishing a varied selection of papers from a two-day conference that Judith Thompson and I co-organized at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, in October 2009. “The Art and the Act: John Thelwall in Practice” sought to highlight the conjunction of arts and acts in Thelwall’s theory and practice, while bringing together the British and North American Thelwall communities in a geographically and historically significant location. An Atlantic midway point between the UK and the US, Halifax was the site of a Canadian, and more specifically Nova Scotian, conjunction of literature, oratory, and reform, manifest in the achievements of the nineteenth-century journalist and politician Joseph Howe, the inventor and speech scientist Alexander Graham Bell, and the adult educator and co-operative movement pioneer Moses Coady.

Both the conference and this volume take inspiration from Thelwall’s ideal of unrestricted intellectual exchange in an expanded public sphere. Insisting on the futility of government attempts to silence the radical movement through arrests, surveillance, harassment, and “gagging” laws, Thelwall remarked that ‘a sort of Socratic spirit will necessarily grow up, wherever large bodies of men assemble. Each brings, as it were, into the common bank his mite of information, and putting it to a sort of circulating usance, each contributor has the advantage of a large interest, without any diminution of capital. (“Rights” 401)’ Adapting Thelwall’s metaphor to the present day, we see Romantic Circles as the “common bank” to which scholars can each contribute their mite to enact “a sort of Socratic spirit” through the electronic circulation of ideas. This collaborative effort will, we hope, generate a “large interest” both by attracting a wider audience for Thelwall’s works and by taking advantage of the unique capacity of Romantic Circles to re-connect the printed word with image, voice, and gesture in the dynamic way for which Thelwall himself was renowned.

In addition to this “Praxis” volume, the larger project John Thelwall: Recovery and Reassessments will include two components in the “Scholarly Resources” section. “John Thelwall in Time and Text” combines a chronology of Thelwall’s life and times with the fullest bibliography to date of his published works, letters, and manuscripts. The result of a collaborative pooling of “mites” of information at the Thelwall conference in Halifax, this “common bank” offers a much-needed resource for the study of Thelwall, especially in the continuing absence of a modern or complete biography.

We hope that it will be updated to reflect new discoveries and connections, perhaps in conjunction with biannual Thelwall conferences.

The second scholarly resource to be offered here is “John Thelwall in Performance: The Fairy of the Lake,” which documents the first full production of a Thelwall play, his Arthurian romance The Fairy of the Lake of 1801, a politically and autobiographically resonant allegory of the times. A co-production by the Dalhousie University Theatre Department and the Halifax-based Zuppa Theatre Company, the play opened in October 2009 in conjunction with the Thelwall conference. Footage of the performance brings to life the oral and performative dimensions of Thelwall’s practice discussed in several contributions to this volume. The accompanying interviews explore the challenges and decisions involved in updating a piece of radical Romantic theatre for modern audiences, while the essay by Judith Thompson illuminates the Fairy’s origins and literary contexts, and locates it within Thelwall’s oeuvre.

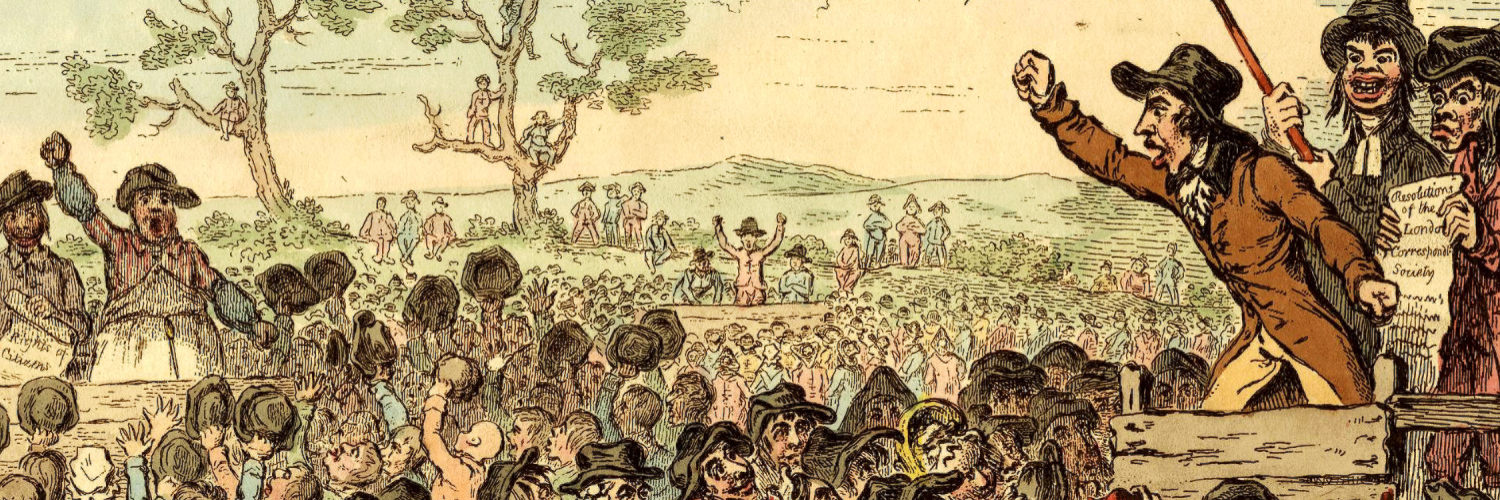

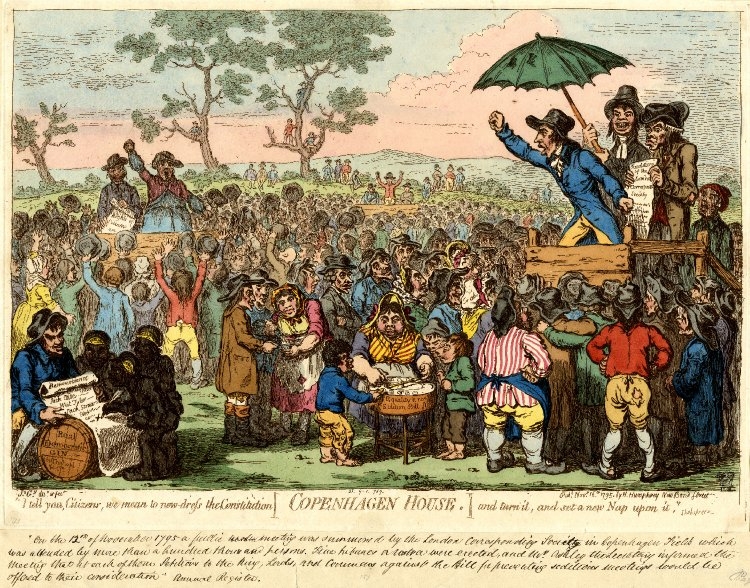

Together these three components of “John Thelwall: Recovery and Reassessments” take advantage of Romantic Circles’ interconnected hypermedia platforms to offer an online equivalent to the multiple platforms erected at the mass meetings of the reform societies in the mid-1790s, where Thelwall’s voice reached thousands. (Thelwall objected to the political system of “virtual representation” championed by Burke, but had he known it as a digital phenomenon, he would surely have embraced it as yet another means of expanding the public sphere.) The caricaturist James Gillray’s depiction of Thelwall addressing the crowd that gathered in the fall of 1795 at Copenhagen Fields, outside London, has become iconic in studies of radical Romanticism.

A line inscribed below the image has him declaring, “I tell you, Citizens, we mean to new-dress the Constitution, and turn it, and set a new Nap upon it.”

In fact he called on his audience to speak out in a “manly, determinate, and constitutional way” in defence of their liberties without fear of reprisals, while reminding them that even William Blackstone, in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, had regarded the resistance of oppression as a constitutional right (Speech-Nov 19, 9). With characteristic rhetorical flourish he added, “it is better to have your throats cut like the Pigs you have been compared to, than to be hanged like the Dogs to which you have not yet been assimilated” (18). As Steve Poole notes in his contribution to this collection, Gillray depicts Orator Thelwall ambiguously: he faithfully captures Thelwall’s physiognomy and elevates him in dress and position above the other figures, but he also expresses a potentially incendiary anger in Thelwall’s clenched fists and open mouth.

Yet firebrand orator was only one of Thelwall’s many modes and personas. Echoing Machiavelli, Thelwall declared that ‘[u]niformity of principle and versatility of means are perfectly reconcilable; and he who wishes to promote the public cause must vary his mode of action with the change of time and circumstances: as the same line of conduct may be at one time beneficial, and at another injurious. (Speech-Nov i)

’ Following Thelwall through his diverse “modes of action” is one of the main challenges for Thelwall scholars today. How specifically did he adapt his practice to the times, and in keeping with what principles? In seeking to answer those questions, the essays collected here also aim to reassess existing Thelwall scholarship.

Both objectives come into focus in Nicholas Roe’s opening contribution, which considers what factors might have drawn Thelwall westwards in the summer of 1797, when he made his watershed visit to Wordsworth and Coleridge in Somerset. In his groundbreaking 1990 essay “Coleridge and John Thelwall: The Road to Nether Stowey,” Roe recovered the story of a close friendship and political affinity that Coleridge tried later to suppress. Returning to this important moment in literary history, Roe now takes stock of two newly republished essays that Thelwall composed at this time: “A Pedestrian Excursion through Several Parts of England and Wales during the Summer of 1797” and “The Phenomena of the Wye, during the Winter of 1797-8.” For Roe, the essays’ non-chronological publication and conspicuous silence on the subject of the Stowey visit reflect the depth of Thelwall’s disappointment when his hope of friendship and intellectual fellowship among the poets failed to materialize. Roe’s essay thus contributes to the recent case for continuity in Thelwall’s practices before and after 1797, when he retreated into “exile” on a small farm in Wales, from which he re-emerged four years later a self-made professor of elocution and speech therapist. In Roe’s view, Thelwall’s excursion of 1797 did not mark a retreat from metropolitan radicalism so much as a reorientation toward the “more subjective mediated vision” of the “Wye” essay that would find fuller expression in Thelwall’s Poems Chiefly Written in Retirement of 1801.

As Roe’s essay makes clear, the “Pedestrian Excursion” and “Wye” essays are also noteworthy for giving voice to the remarkable diversity of identities that Thelwall adopted throughout his life and career: not only writer and orator, theorist and therapist, journalist and critic, but also agriculturalist, antiquarian, historian, economist, industrialist, painter, pedestrian, and picturesque traveller. That last, still largely unfamiliar persona comes to the fore in Mary Fairclough’s essay on the evolution of Thelwall’s engagement with the politics of the picturesque, notably in the “Pedestrian Excursion” and “Wye” essays. Challenging E. P. Thompson’s view that the essays’ “conventional rehearsals” of the discourse of the picturesque demonstrate Thelwall’s failure to sustain his radicalism in the face of persecution, Fairclough argues that they in fact carry forward an attempt begun in The Peripatetic to “rethink and recalibrate such engagement” and develop alternative means of “seeing” the landscape. In Fairclough’s view, Thelwall achieves a material exploration of the landscape and its social configurations that at least partially reconciles it with his political radicalism and anticipates his renewed public engagement in the next decade, also on materialist principles.

The pervasive influence of Thelwall’s scientific materialism—his belief that all life is a result of the modification of matter

—is the subject of Molly Desjardins’s essay on the political, elocutionary, and therapeutic implications of Thelwall’s associationist understanding of the human mind. Reading Thelwall’s observations on the treatment of speech impediments in A Letter to Henry Cline (1810) alongside the earlier materialist arguments of An Essay towards a Definition of Animal Vitality (1793) and the associationist premises of a much later essay “On the Influence of the Scenery of Nature,” Desjardins calls attention to the consistency of Thelwall’s aims across decades and modes of action: both as a political activist and an elocutionist, she argues, Thelwall employed his electrifying powers of speech as a sort of “vital stimulus” to form and re-form associations within and between minds in an expanded public sphere.

Thelwall’s attention to the individual body as an instrument of communication and microcosm of the body politic is a recurrent focus of the essays in this volume and of other recent scholarship.

With Emily Stanback’s contribution, however, a new dimension comes into view: the impaired body as the site of an ideological struggle that shaped modern attitudes towards disability over the next two centuries. Analysing Thelwall’s little-known writings on the treatment of speech impediments and “idiocy” in the context of the history of medicine, Stanback calls attention to alternative manifestations of Thelwall’s humanizing, democratizing ideals. At a time when attitudes toward illness and impairment were still inconsistent yet often pathologizing and marginalizing, she argues, Thelwall offered a strikingly progressive and egalitarian approach guided by a lingering Jacobin faith in the human capacity for self-improvement. In the process, Thelwall seems to have anticipated a modern definition of autism and ventured some of its earliest recorded descriptions.

Thelwall’s interest in “the enfranchisement of the fettered organs” (Cline 9) was no doubt influenced by his own efforts to overcome the speech impediment for which he was nicknamed the “Lisping Orator” (Mrs. Thelwall 40); it was also shaped by his struggles with the legal and political impediments to free expression imposed throughout his career. Despite both forms of impairment, Thelwall became renowned as a powerful speaker. His epitaph records that “[i]n his utterance Englishmen experienced the full beauty and energy of their native speech. His oratorical powers were only surpassed by his devoted zeal and unflinching efforts to promote the best liberties of his fellow men.” Hazlitt described Thelwall more ambiguously, as “[t]he most dashing orator I ever heard [. . .], a volcano vomiting out lava” (264).

Those who objected to his politics, meanwhile, saw Thelwall’s oratory as a ready target for satire. He appeared in the anti-Jacobin novels of the day as Citizen Ego, John Bawlwell, and the regicidal Mr. Rant.

As Nicola Trott remarks of this last portrayal, so we might say of them all that they amounted to a second and arguably more successful trial for high treason (xii). And this “trial” was not confined to literature.

In an unprecedented analysis of the role of visual satire in shaping Thelwall’s public profile, Steve Poole examines the often contrasting strategies by means of which loyalist caricaturists, notably James Gillray and Isaac Cruikshank, “negotiated and accommodated” Thelwall’s uniquely recognizable features and demonstrative oratorical manner. A complex and ambiguous symbol of radical energy until his retreat to Wales in 1797, Thelwall thereafter became “a cartoon signifier of radical defeat and deflation.” Poole’s essay illuminates the iconography of the period as well as the philosophical and physiognomical debates that informed it, in which Thelwall himself was engaged. Taken together, Poole notes, these caricatures offer a visual commentary on what E. P. Thompson referred to as the hunting of the “Jacobin fox” (“Hunting”). Indeed, Poole regards Thelwall’s return to politics in the 1810s and 1820s as “relatively unconvincing.” In his view Thelwall did not so much redirect his earlier energies as dissipate them in uncontroversial “professional” channels.

Clearly, the nature and extent of Thelwall’s radicalism after 1800 remains an open question, and answering it demands closer attention to his later pursuits. This is precisely what Angela Esterhammer provides in her essay on Thelwall’s short-lived monthly periodical the Panoramic Miscellany. Launched on the model of the Monthly Magazine after Thelwall’s cursory dismissal from its editorship in 1825, the Panoramic aimed to continue the Monthly’s mission of public information and improvement. Esterhammer shows that while observing many common journalistic practices of the time, Thelwall’s Panoramic stood out for its international outlook and, above all, its “dialogic orientation.” In various ways, the Panoramic sought to provoke quasi-conversational exchange with its male, middle- and working-class contributors and readers, while taking a more deliberately didactic approach to female readers. For Esterhammer, the Panoramic demonstrates the persistence of Thelwall’s commitment to public education, criticism, and unrestricted communication even as late as 1826. Her essay complements Michael Scrivener’s earlier analysis of Thelwall’s journalism in the Tribune, the Champion, and the Monthly Magazine (“The Press”), and should also be read alongside Scrivener’s republication of several of Thelwall’s letters from this period, both for a sense of the financial aspects of his late ventures and for his pained awareness that by 1832 he was already slipping out of the “liberal remembrances of the now triumphing advocates of Reform” (“Letters” 149).

Although the Panoramic Miscellany was to be Thelwall’s last published work, his legacy as a writer, lecturer, artist, lover, and peripatetic adventurer found new and sometimes paradoxical expression in his children, and especially his son Weymouth Birkbeck (1831-1873). In her often surprising closing contribution to this volume, Patty O’Boyle reconstructs the story of the life and career of this “son of John Thelwall” as he continued and subverted his father’s talents and principles, carrying early nineteenth-century Romantic idealism into the colonial heart of darkness in Central Africa. By lifting the pall of anonymity that has long rested on this last direct descendant of John Thelwall—whose middle name was a tribute to the founder of the mechanics’ institutes at which Thelwall lectured around the time of Weymouth’s birth in 1831—O’Boyle also sheds light on his father’s life and achievements from a longer historical perspective. In tandem with the essays by Poole and Esterhammer, O’Boyle’s essay begins to address the vexed question of Thelwall’s eclipse and persistence in the nineteenth century.

All together, the essays collected here mark both continuity and new directions in the rapidly emerging field of Thelwall studies. Much like Thelwall and Coleridge in the mid-1790s, they “answer and provoke”

each other on topics of mutual interest, notably Thelwall’s scientific materialism; his use, figuration, and treatment of the speaking body, both real and imagined; the connection between his printed and spoken words; his historical legacy; and the adaptability of his modes of action. In the context of the recent surge of interest in Thelwall, these essays also testify to the continuing relevance and appeal of his “radical” principles. Efforts are now underway to launch a Thelwall Society and erect a commemorative English Heritage “Blue Plaque” in London, where in 2014 a major Thelwall conferenc e will explore his relation to medical science and mark the 250th anniversary of his birth. The launch of a Thelwall Web site, a modern edition of his abolitionist, feminist novel The Daughter of Adoption (1801), and the publication of two monographs on his work all promise to help sustain the pace of this ongoing recovery.

If, as Steve Poole has noted, it can no longer be maintained that by 1800 the “Jacobin fox” was dead (Introduction 11), this volume and the larger network of activities to which it belongs confirm that Thelwall and his body of work are finally finding new life.

Judith Thompson and I wish to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), the University of King’s College, and Dalhousie University for their support of the conference “The Art and the Act: John Thelwall in Practice” on which this Romantic Circles project is based.