Let me begin by quoting a well-known Byronic passage:

. . . I rose,Forgetful of our former woes;And rushing from my couch, I dart,And clasp her to my desperate heart;I clasp—what is it that I clasp?5No breathing form within my grasp,No heart that beats reply to mine,. . .And art thou, dearest, changed so much?As meet my eye, yet mock my touch? (III.1287-92)10

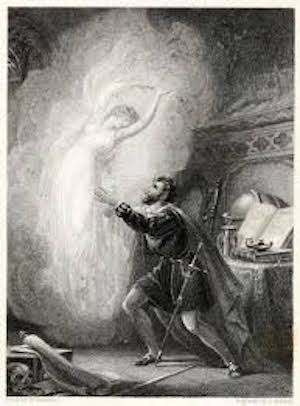

While this passage is taken from Byron’s fragment tale, The Giaour, written in 1813, the illustration I have provided above depicts a very different hero attempting to embrace his own lost love, the spirit of Astarte from Byron’s 1817 dramatic poem, Manfred. And yet, unless you knew something about Byron’s poetry, it would be difficult to distinguish between the poetic narrative of the Turkish Tale and the image I have shown you. The text appears to match the image very closely. Nor is this the only similarity between the two poems: critics and reviewers have long remarked on their shared indulgence in mysteries around unspoken and unspeakable crimes and representation of gothic action, made only darkly visible in The Giaour through a multi-perspectival and fragmentary structure and in Manfred by its echoing of what Byron referred to as Augusta’s “absurd, obscure hinting style of writing full of megrims and mysteries” (BLJ V:231-2). They have also long been associated with obfuscation and scandal if not because of their poetic style then at least because of their shared plot details

—we might remember the Giaour’s insistence that he did not kill his lover (“Not mine the act, though mine the cause,” [1061]), and Manfred’s similar confession (“I loved her, and destroyed her . . . Not with my hand, but heart . . .” [II.ii.117-9]). Arguably, this was rather a moot distinction for the heroines in question.

These strong textual resemblances, however, serve to highlight the very different manner in which these very works have been approached by the artists and illustrators of Byron’s poetry. Exploring some of the most widely circulated nineteenth-century illustrated editions reveals that the character of Leila is rarely represented, with artists preferring to focus on the vendetta between men—the Giaour and Hassan—which is the real “action” at the heart of the poem. One can choose from a wide array of images of these two testosterone-driven men, locked in a deadly, albeit vaguely libidinal, combat, while Leila appears very rarely. On the other hand, Leila’s spectral sister, Astarte, has a much more material presence in these printed texts and appears countless times in engravings or illustrations.

What I would like to explore in this essay is the way in which the illustrations of these two heroines reveal a great deal about the public response not so much to Byron’s poetry, but rather to their own projected narratives and fantasies about Byron on to his poetry. Perhaps counter-intuitively, I will argue that by taking a careful look at the ways in which Byron’s heroines are illustrated, we are granted a window into the public view of the poet himself.

To begin with the erasure of Leila, one must ask why poor Leila is left to languish in poetic oblivion while Astarte is so frequently represented. Given that their stories are so similar, why are not their visual fates?

On one level the answer is probably pretty straightforward. The plot of The Giaour is often read as political allegory, and Caroline Franklin reminds us that, while the character of Leila is in part based on a real woman “rescued” by Byron while on his travels, she is also strongly “compared to [her] native land of Greece” (38-40). Critics such as Jerome Christensen (93), and David Roessel (56), specifically associate her form with the image of the corpse-like Greece, the victim of Turkish oppression and violence,

while Alan Richardson complicates this reading by drawing our attention instead to Leila’s identity as a Circassian Beauty—the quintessentially desirable woman in nineteenth-century terms (221). Even while playing a role in such political allegories, however, she stands in for a type (the Orientalized, Eastern beauty), rather than an individual woman.

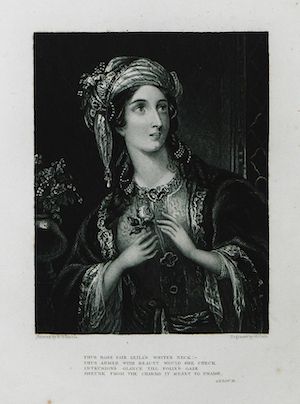

As such, it is possible to read Leila not as a woman or as a fully defined character, but rather as a marker in a political allegory: the symbol of a victimized and Orientalized beauty, the site of political turmoil and hybridity, or very specifically as “Greece, but living Greece no more! / So coldly sweet, so deadly fair” (Giaour 91-2). Certainly, the few images we have of her show her in a highly Orientalized dress, vaguely vapid in appearance and often staring into the middle distance (Figures 2 and 3).

She is just one of the many Byron “Beauties” to appear in the popular collections depicting the leading ladies of his poetry, which serve as a mere pretext for the creation of exotic albums filled with lush images. In no way do these engravings serve as illustrations of the poems or their action, and what is notable about Leila’s image is that she could be represented by any young woman from the Peloponnese.

Astarte, however, has a far more complex and sensational history. One reason for this is that she was based on a real woman and was repeatedly identified as a representation of Byron’s half-sister and lover, Augusta Leigh. As Peter Manning quite rightly observes, “In an understandable effort to circumvent the scandalmongering that befuddled earlier interpretations, criticism has tended lately to minimize the importance of incest in the drama” (77). Modern critics are wary of indulging in biographical readings of the play and even when read biographically, recent criticism has denied Augusta her role in the drama. Peter Cochran thus argues that “Astarte—all that Manfred offers by way of heroine—is often taken, by those intent on creating sensation at all costs, to be a version of his half-sister Augusta; but I’d argue that in her remoteness and verbal economy Astarte is closer to Annabella” (Manfred 15).

And yet, whatever modern criticism might think of Astarte’s identity or poetic function, Byron’s contemporaries were generally in agreement that Augusta was the model of Manfred’s criminal love.

Having said this, I won’t rehearse the, indeed, sensational and often unpleasant details of the affair between Byron and Augusta, nor go over all the shocked references to it by the poem’s reviewers. To summarize briefly: when Manfred was published in 1817, shortly after Byron’s ignominious departure from England, London society was waiting for yet more scandal to feed the growing interest in the unfolding saga of his separation from Annabella. Few reviewers of this new poetic drama missed the fact that Astarte was described as the sister and the lover of this Byronic hero, and the commentaries on the poetic drama did little to quell the crescendoing gossip. La Belle Assembleéremarked rather coyly that “this drama is interesting, yet there are many domestic allusions, from which works of a dramatic nature should ever be free” (Reiman II:107). The European Magazine, however, issued its own more damning and decidedly more pointed review of Manfred in August of 1817, first summarizing the incest plot for its readers and then suggesting that this crime was the key to—if not Manfred’s—then at least the poet’s hidden meaning. Here, we are told, the “wretched brother more fully, though still darkly and ambiguously, alludes to the early circumstances of his life, (which) will more clearly enable readers to judge if we have made a correct guess at the elucidation of the noble poet’s story” (Reiman II:963). Such reviews seem mean spirited, but there is much to suggest that Byron was very aware of the brouhaha that he would create with Manfred’s publication. He noted in a letter to Augusta written in March of 1818 that he is curious as to whether the publication of Manfred has caused a “pucker” (qtd. in Lovelace 168). Augusta wrote back that she had been hurt both by the subject matter of the poem and by Byron’s apparent insensitivity to her plight, left behind as she was to face the Manfredian music on her own. “A propos of ‘puckers’ I thought there was unkindness which I did not expect, in doing what was but too sure to cause one—& so—I said nothing—& perhaps should not but for your questions” (qtd. in Lovelace 168). And a pucker there was. The Hon. Mrs. Villiers, an ally of Annabella Milbanke, wrote to the poet’s estranged wife that the Day and New Times of June 1817 had released a review of Manfred in which “the allusions to Augusta are dreadfully clear. No avowal could be more complete. It is too barefaced for her friends to attempt to deny the allusion” (qtd. in Lovelace 166).

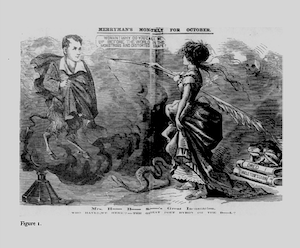

So strong was the assumption that Manfred represented Byron’s (as well as his tortured hero’s) confession of a secret sin that other reviewers also made explicit reference to it. The reviewer for the Theatrical Inquisitor, for example, worries “we hope for the sake of manhood and morality, that the rumor is incorrect which has identified his inmost feelings with the subject before us” and we as readers are urged to “turn away from this book at this repulsive point” (Reiman V:2266-7). Indeed, many critics in either veiled or quite brazen terms make reference to Manfred as a potential clue to the events leading up to the poet’s separation from his wife. Their greatest frustration, however, was that Byron’s absence from England made it impossible to see the effect that these accusations and condemnations had on him. Guilt could not be read on his countenance as one might the visage of any of his great “Conradian” heroes because he was well and truly hidden from society’s gaze. This was Byron’s great advantage and Augusta’s recurring tragedy. For, if Byron’s behavior could not be scrutinized for signs of moral depravity and guilt, then his partner-in-crime’s behavior could. It is for this reason that Augusta, left to the vigilant reforming zeal of Annabella and her circle, was rigidly policed and regimented so as to erase or obfuscate any possible outward signs of a criminal relationship to Byron. She was publicly “forgiven” and supported by Annabella, but only to ensure that she did not go to join her half-brother in Italy; her letters were rewritten by Annabella and her actions supervised so as to produce the most convincing image of innocence. In so doing, Augusta protected not only her own reputation, but Annabella’s as well. Augusta agonized over how to redeem her reputation after Byron’s departure, and when the spectral shadow of her past rose before her in the image of Manfred’s Astarte only a year later it was a considerable blow. What Augusta knew, and what Byron failed to acknowledge, was that it was not to the Byronic hero of Manfred to which the public turned to decipher the truth of the poet’s incestuous relations, but to Astarte/Augusta. Augusta quite literally stood in for Astarte in the popular imagination of the day, as is made very clear by the infamous publication of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1869 Lady Byron Vindicated. Stowe, freed from her promise of discretion to Annabella by her death, reveals to the world “the truth” about Augusta and Byron (236-7). A cartoon that appeared in Merryman’s Monthly in October of 1869 makes the connection to Manfred very clear, referencing as it does in its description, Stowe’s raising of Byron’s demonic spirit in this writer’s own version of the Manfredian “Incantation.”

As Jerome McGann alerts us, the Incantation was thought to refer back to its 1816 iteration as the fragment of a Witch’s Drama, commonly believed to be a sly swipe at Annabella.

Here, Manfred/Byron appears as a demonic spirit through Stowe’s conjuring. It came as no surprise, then, when Ralph Lovelace, Ada Byron’s son,

felt the need to publish his own 1906 defense of his grandmother under the title, Astarte: A Fragment of Truth. As he observes in the purple prose for which the entire text is remarkable, “Astarte (Augusta) was haunted and ridden by a spectral Astarte vivified for a flash of time out of the eternal silences to prophesy judgment by the infernal gods upon Manfred” (Lovelace 70). For Byron’s contemporaries and even for subsequent generations, Manfred was a play that was first and foremost about deciphering Augusta, for it was only by reading and understanding her poetic incarnation, Astarte, that one could now hope to learn anything about the poet himself.

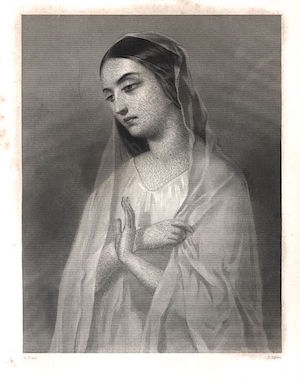

With this in mind, what are we to make of the ways in which Astarte is depicted? One of the earliest images of Astarte appears in Finden’s Byron’s Beauties in 1836.

Like the images of Leila we have already seen, the image of Astarte in Finden’s Byron’s Beauties (Figure 6) is taken out of its narrative context—even more so than in the illustrations of Leila who at least looked appropriately Turkish in dress. Finden’s Astarte, however, is represented as a Greek goddess, perhaps gesturing to a Hellenized version of the Persian deity, Ishtar. In true Hellenic style, she sports carefully coiled hair, Chiton, and an arm bracelet. Innocent and demure, this Astarte seems an unlikely partner for Manfred, not to mention her being curiously dressed for a resident of the Alps. The text that accompanies the heroine’s image is noteworthy: Byron’s heroines, it is insisted, “are solitary symbols of loveliness which need no foil” (Finden vii). They are admirably adapted for isolated pictorial illustration, we are told, since their charm exists not in “the dramatic action in which they are engaged,” but “in their intensity of individual feeling” (Finden vii). The artist of this portrait of Astarte is careful to remove any possible hint of a context that might draw the reader’s attention back to the action of Manfred and its scandalous associations in part because this album was produced specifically for young women and devotees of the poet. The illustration itself is accompanied by a long quotation from “Professor (John) Wilson,” a frequent contributor to Blackwood’s Magazine where he served on the editorial board, often publishing under the alias “Christopher North.” Wilson, who was made professor of moral philosophy at Edinburgh University in 1820, positions Astarte as “young, beautiful, innocent.” He does not deny her guilt but assures us that she has been “murdered—judged [and] pardoned” (qtd. in Finden vii). She was, Wilson insists, a soul cleansed of sin: “At last, she rises up before us in all the mortal silence of a ghost, and with fixed, glazed, and passionless eyes, revealing death, judgment, and eternity” (qtd. in Finden vii). What we find in her figure, then, is all passion spent. If there had been any guilt, we need not concern ourselves with it. Innocence and purity now reside in her looks and the implication is that, since a judgment has already been passed on Byron, the presumed instigator of the crime, it would be presumptuous of us to attempt a judgment of our own. Along these same lines, a production of Manfred was mounted in Covent Garden in 1834 for a total of 36 performances.

Augusta attended one of them and saw herself represented in angelic form, surrounded by spirits as she embarked on the salvation of her fictional brother. In this adaptation of the play, when Manfred is about to die, Astarte appears before him and cries out: “Manfred! Look up! I do forgive thee” (qtd. in Cochran, Theater 175).

And so again, all is forgiven, heaven sought, judgment passed.

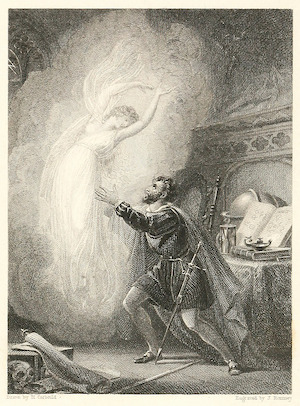

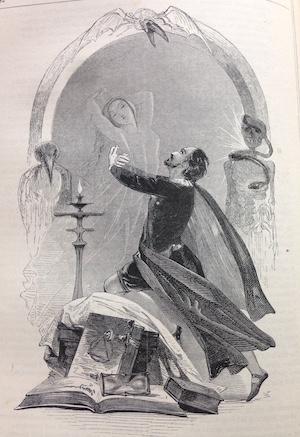

In two slightly later illustrations, we see the act of judgment in process. In an 1838 illustration (Figure 7), Manfred reaches out to embrace Astarte, who, again looking like a Hellenic deity, arches away from his grasp in a gesture of modesty and evasion.

She is surrounded by a bright cloud or nimbus and her arms stretch up to the heavens. Manfred’s gesture, while clearly reaching out to the image, is as much one of adulation and reverence as desire. His sword points down to the ground in the shape of a cross and a skull lies in the corner as a memento mori. The room he inhabits is in every other way, scrupulously academic, with open texts, a globe, and instruments. The second image (Figure 8), almost certainly crudely copied from the first (circa 1854), represents a similar composition but a very different moral.

Astarte is now a voluptuous siren, her breasts fully exposed to her brother’s gaze beneath her diaphanous shroud. Manfred encircles the form in a gesture of passionate excitement, his robes rising with his sudden movement. His sword has morphed into a candelabra that symbolically burns, shall we say, rather brightly. The background has also undergone a tonal shift; it is now a sepulchral and gothic space, its décor given to skulls, crows, and snakes. Astarte, far from reaching up to heaven in a celestial arabesque, now reaches behind her head, her hand a claw that visually echoes the beak of the vulture above her. The iconography is equally clear. In this interpretation of the action, Manfred and Astarte have been judged—and damned—for their sins.

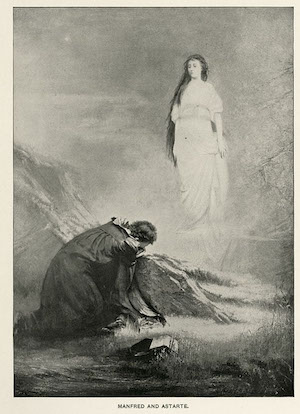

By the mid-century, the interpretive attitude to Byron’s drama and potentially to Byron’s judgment shifted again. Astarte has left the pagan Elysian fields for a more conventional realm of Christian blessedness. It would seem that a pagan gesture of forgiveness from a Hellenic Astarte was too ambiguous for Byron’s defenders: the blessing now had to come from the Virgin Mary herself. Indeed, in the following two images of Astarte, dated 1849 (Figure 9) and 1891 (Figure 10) respectively, the young woman takes on all the iconographic attributes of the intercessor of man with God. In the first image, the iconography is so reminiscent of classic Mariology as to belie the context of Manfred all together. She might as well be an icon. In the second image, the artist at least places Manfred in the picture, who bends in reverence to the spirit before him.

A book lies open on the ground beside him and gone is the paraphernalia of the sorcerer dabbling in an infernal realm. This is an image of a sinful man in a state of repentance and humility—hardly the image of Byron’s disdainful Manfred who defies the spiritual forces that threaten him with a sneer.

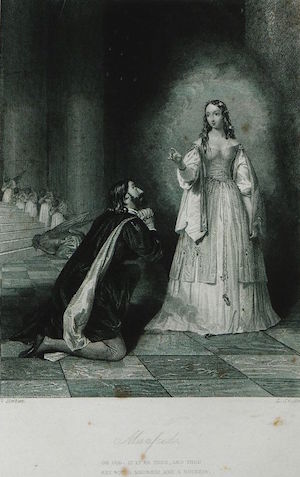

The final Astarte image I want to discuss, however, is by far the most interesting. (Figure 11)

The original painting is by John Roberts Herbert, who produced several Byron illustrations in the late 1830s, including images of Don Juan, the Corsair, Beppo and Foscari, all circa 1838.

Once more we have the Madonna and penitent composition that we have seen before, but with some important variations. At this point, even the book has disappeared from Manfred’s side, and he now simply kneels, hands clasped in supplication before the figure of Astarte, who is once more surrounded by a celestial nimbus. But the lovers are no longer alone. Now a row of angels can be seen lining the wall behind the central figures, their heads buried in their hands in sorrow.

How are we to read this interpretation of the action? Is this an image of the act of forgiveness with the angelic host appearing as evidence of Astarte’s innocence and thus Manfred’s redemption? Arguably not. In fact, this engraving is the most damning of all those we have seen thus far, partially because in this representation of Astarte, unlike all the others, she is depicted in modern dress. No longer does she resemble a goddess, a muse, or even the Virgin Mary—now she looks like a young woman just about to step out for a ball. If one studies the dress style of the late 1830s and early 40s—tight bodice, layered with an overskirt, full sleeves and off the shoulder cut—one sees that this Astarte embodies it perfectly. (Figure 12) Even the chain girdle that hangs from Astarte’s waist (something that was very popular in the sixteenth century, it is true) made a fashion comeback in 1836 London as a Chatelaine. (Figure 13)

Herbert has carefully woven elements of the old and the new here, but his Astarte would not at all be out of place in a contemporary society ballroom—or, indeed, in Augusta Leigh’s circle.

What is Herbert doing in this image? Why is his Astarte so clearly marked as a modern woman? The answer, of course, is that he has very cagily drawn the acknowledged but unspoken parallel between Astarte and her supposed biographical model, Augusta. If this hypothesis is correct, then the message does not bode well for Byron’s spiritual state. For, while it is possible to read the gesture of Astarte as one of absolution, I think this unlikely given a comparison with a second Herbert painting from 1851, “The Judgment of Daniel” (Figure 14).

Here, too, the blessed figure holds a hand up in exactly the same gesture that we see from Astarte, but in the case of Daniel, we can be certain that this expresses condemnation and not absolution, since he is in the process of condemning the elderly judges to death for their false accusations of Susanna, now found innocent of adultery.

The Byronic hero is explicitly being chastised and judged by Augusta’s stand-in, Astarte. Penitent though he may appear, he is not forgiven, and the angels weep in despair at the sight of his figure bathed in ominous shadows. Unlike the Covent Garden Astarte, this spirit does not speak in a voice of forgiveness, but her lofty silence speaks volumes.

To conclude, there is something rather poignant in these many nineteenth-century images of Astarte as a powerful force who dominates, judges, and directs the Byronic hero’s moral path. For if ever there was a figure less likely to be held up as a moral guide, it was Augusta. But we have been complicit in this process too: our critical reluctance to be seen as sensational and our refusal to study the very real role that Augusta played in Byron’s life, creative or otherwise, has silenced Astarte/Augusta and made her as invisible as Annabella could have wished. This is not to say that Augusta and the issue of incest should be seen to be at the heart of Manfred or indeed any other text by Byron—but to ignore her presence seems to me equally wrongheaded. Having been silenced and bullied into at least the performance of middle-class morality after Byron’s departure for the continent, Augusta, alone and isolated, was never allowed a public voice again. On her deathbed, after a painful decline, she had tried to communicate one last message to the world. Predictably, it could not be understood.