I want to begin with Manfred on the Jungfrau, one of the poem’s key moments of reckoning in which Byron’s hero struggles to apprehend the trajectory of his own fall and end, literally and figuratively. Contemplating a leap from the precipice to his death on the rocks below, he also meditates Satanically on the vector of his moral degeneration and the death-in-life that it has entailed:

There is a power upon me which withholds,And makes it my fatality to live;If it be life to wear within myselfThis barrenness of spirit, and to beMy own soul’s sepulchre, for I have ceased5To justify my deeds unto myself—The last infirmity of evil. (I.ii.23-9)

This essay amounts essentially to an extended footnote to those lines—and particularly to those final clauses: “for I have ceased to justify my deeds unto myself—the last infirmity of evil.” I hope to expose some unresolved energies or faultlines in this passage that divide the moral vision of the play. As the driving action throughout, Manfred pursues a certain kind of cessation or relinquishment, the dark twin or obverse of the repentance and recalled curse that determines Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound. Manfred tells the Witch of the Alps that his solitude is “peopled with the Furies” (I.ii.131), just as Shelley’s Prometheus is tormented on his rock by Jupiter’s “tempest-walking hounds,” who show him visions of his own terrors (Promtheus Unbound I.331). That is, both heroes are tortured by furies that are also interior anxieties and fears (one might say that the various scenes of supernatural aggression in both works are essentially records of panic attacks). Both heroes have something to get over: Prometheus, his vengeance and Manfred, his conscience. Manfred the play offers a mordant, Byronic version of the thesis that Shelley will also advance in his philosophical psychodrama: you become a demi-god by giving things up. In relinquishing his anger, Shelley’s hero regenerates the cosmos and also makes himself oddly irrelevant: his Puff-the-Magic-Dragon-like retreat to a cave where he will sit with Asia “as the world ebbs and flows” (III.iii.24) marks both his ascension and retreat into pair-bonded solipsism. Manfred’s quest is more ostentatiously self-centered, and yet he pursues a form of emptying out that might negate the self entirely. Manfred is a dead reckoning of the negative way.

So, to begin: how do we gloss these lines? The interpretive problem starts with the quadruple negative, further destabilized by one of Byron’s ambiguous dashes: “I have ceased / To justify my deeds unto myself— / The last infirmity of evil.” Two primary questions arise. First, is it the justification of one’s ill deeds, or the cessation of that justification, that Byron intends as “the last infirmity of evil”? The dash makes it possible for the final phrase to govern either the infinitive (“To justify my deeds unto myself”) or the entire preceding clause (“I have ceased to justify my deeds unto myself”). Second, by “the last infirmity of evil,” does Byron mean the ultimate stage of evil, or the last remaining flaw in evil’s otherwise-perfect constitution?

Maybe Milton can help. Byron’s “last infirmity” phrasing adapts a passage from “Lycidas”:

Fame is the spur that the clear spirit doth raise(That last infirmity of Noble mind)To scorn delights, and live laborious dayes. (70-3)

For Milton, “last infirmity” means the final remaining weakness after all other errors have been purged. “Fame is the spur,” but it also remains a recognizable flaw in a “Noble mind” that should be above concerns for applause and praise. Moreover, Milton himself is here adapting a line from Tacitus’s Histories (IV.6): “etiam sapientibus cupido gloriae novissima exuitur (the desire for glory is the last thing relinquished, even by wise men). So, as Byron inherited the phrase, “last infirmity” meant the final weakness to be overcome or shed, the longest-lived flaw. But “last infirmity of evil” complicates the question—since evil itself can be thought of as infirmity, and thus the “last infirmity” would be in fact the crowning weakness, the consummate infirmity, the final summit or stage of descent into pure evil.

We are left with two options so far: whatever the phrase “the last infirmity of evil” modifies, that thing is either the last grace, the final scrap of goodness that mitigates evil (a “last infirmity” in the mode of Milton and Tacitus), or the last step on the ladder of degeneracy, the ultimate state of sin. So, what does the phrase modify? Well, again we have two primary opposing choices: either the claim “I have ceased to justify my deeds unto myself” or the infinitive “to justify my deeds unto myself”—that is, either self-justification or the cessation of it. These oppositions, then, ultimately resolve into two primary interpretive choices, once you cancel out the positives and negatives: self-justification is either the worst thing or the last hope in the moral vision of Byron’s play.

Jerome McGann has indicated that he sees Manfred as a critique of hypocrisies and an exposure of self-deceptions. He writes in Byron and Romanticism: “We are sinners who want to cover our sins, to mitigate their depth. This desire is precisely ‘the last infirmity of evil’ that Byron wrote his play to engage” (92). In this view, self-justification arises from a guilty conscience, and manifests itself in a dangerous sense of righteousness. Plenty of evidence suggests that this was Byron’s view, particularly around the time of the composition of Manfred, when he was angry at Lady Byron and her allies and raging over the hypocrisies of English society. The “Incantation” from Manfred is precisely an “In-cant-tation,” a curse on cant and an excoriation of the “false tears,” “serpent smile,” “unfathomed gulfs of guile,” and the “shut soul’s hypocrisy” that were at once Annabella’s, her maid Mary Jane Clermont’s, and Byron’s own—not to mention those of Castlereagh and Romilly, whom he hated (I.i.201-71). Those who justify their deeds unto themselves adopt an essentially Satanic moral posture, reversing the polarities of good and evil—“Evil be thou my Good” (Paradise Lost IV.110)—something like James Hogg’s Justified Sinner, who is far more dangerous, far more evil, because of his sense of righteousness. Robespierre and the Terror stand somewhere in the near distance. As Alan Liu writes of the French Revolution, ‘Thus where the plot of the Revolutionary tragedy might have remained the angry sentence, “war demands sacrifice,” Justice at last legitimized demand to make the sentence read, with an assurance and dignity so supernal that we might well think of the angel-interpreter comforting Hagar: “war justifies sacrifice.” (159)’ In other words, to justify evil is to weaponize it, to make it active as not only necessary, but “good.” In such a view, to cease in this self-righteous activity and admit one’s hypocrisies would be a prelude to confession: self-justification becomes the worst stage of evil, while its cessation is the first step and the last grace that might lead to redemption.

The problem with this reading, of course, is that Manfred hardly appears redeemed on the Jungfrau. Quite the contrary, he feels a “barrenness of spirit” as if he has become his “own soul’s sepulchre” (I.ii.26-7). The general thrust of the passage suggests a state of dejection and acedia, as if Manfred has yielded up moral questions in despair. He has ceased to justify his deeds, ceased to provide morally or ethically inflected accounts of his actions, even to himself, and thus attained the summit of evil, having given in to the “last infirmity” in “this long disease my life,”—to allude to the title of McGann’s keynote address, and to Pope (Pope, “Epistle” 132). In such a state, Manfred hears no voice of conscience, not even a perjured one: he just gives up and does what he wants—except he only wants what he can’t have: forgetfulness, oblivion, forgiveness, Astarte. In this view, self-justification is the last grace, and its abandonment signifies a descent into the slough of sin’s infirmity. Yet Manfred still glimpses evil from where he stands: he has not yet moved to a place where “evil” as such ceases to exist—his conscience is not totally gone. Making this statement, he voices a judgment on himself, meaning he has not stepped beyond moral calculation, even though he finds himself on the dizzy brink of complete amorality. He still wants to forget, which means he still remembers; and he will soon plead Astarte for forgiveness, which means he still feels guilt and remorse. It’s not over yet: on the Jungfrau, Manfred is not yet beyond good and evil.

In his opening soliloquy, Manfred asserts a post-mortal perspective, claiming that

Good—or evil—life—Powers, passions—all I see in other beings,Have been to me as rain unto the sands,Since that all-nameless hour. I have no dread,And feel the curse to have no natural fear,5Nor fluttering throb, that beats with hopes or wishes,Or lurking love of something on the earth. — (I.i.21-7)

In this comprehensive devaluation of “all I see in other beings”—good, evil, life, powers, passions—and of his own feelings for earthly things—dread, fear, hopes, wishes, and love—Manfred asserts a cold impermeability to human existence. But there are two things he has not renounced: nature and himself—or, more accurately, the beauty of the external world and his own tormented conscience. Getting over these things will occupy him for the rest of the play. We observe a series of encounters with natural scenes—from the Jungfrau, to the personified Witch of the Alps, to his farewell to the sun, and finally, to his address to the moon shining on the mountains—all of which involve varying degrees of longing and admiration. He says on the Jungfrau, “Beautiful! how beautiful is all this visible world,” but he rejects the Witch of the Alps whose beauty might have redeemed him in a Wordsworthian vein, and he concludes his thoughts on the Coliseum remembering how the moonlight left

. . . that beautiful which still was so,And making that which was not—till the placeBecame religion, and the heart ran o'erWith silent worship of the Great of old,—The dead, but sceptred Sovereigns, who still rule5Our spirits from their urns. (III.iv.36-41)

The turn from nature (moonlight on the Alps) to memory (moonlight on the Coliseum) and thence to “silent worship of . . . / The dead” marks a transition away from external beauty to internal experience, in a recognizably Byronic mode of transfiguration (III.iv.39-40).

In admitting that other spirits rule his spirit, Manfred edges closer to the final renunciation the drama requires. Despite the ostensible defiance and willfulness of the last scene, he undergoes his final relinquishment: essentially, he gets over himself. And his last gesture—to reach for the hand of another human (either Manuel or the Abbot, depending on the version)—suggests a last abandonment of his walled interior stronghold. Perhaps now finally, truly giving up on self-justification, he moves past evil to another order—and I am thinking here of Nemesis saying of Astarte, “She is not of our order” (II.iv.115). In an entry on “applause” in The Gay Science, Nietzsche has occasion to quote the Tacitus passage on the desire for glory: ‘The thinker does not need applause or the clapping of hands, provided he be sure of the clapping of his own hands: the latter, however, he cannot do without. Are there men who could also do without this, and in general without any kind of applause? I doubt it: and even as regards the wisest, Tacitus, who is no calumniator of the wise, says: quando etiam sapientibus gloriae cupido novissima exuitur -- that means with him: never. (sec. 330, p. 144)’ Here we glimpse the case of Manfred, beyond self-justification and beyond Nietzsche’s limits, one who believes he can do without the clapping even of his own hands: “I have ceased to justify my deeds unto myself,” even though that renunciation is always the novissima exuiter, the last thing to go. To escape his self-imposed torments, the bite of conscience, Manfred must also abandon his self-regard: only then, as a kind of stoic empty vessel, can he achieve the calmness of his passing.

As I suggested at the outset of this talk, much of Manfred might be understood as the record of a panic attack or nervous breakdown, with the last lines as aftermath. The same thing happens to Prometheus in the first act of Shelley’s drama: one of the Furies says to him, “we will rend thee . . . nerve from nerve, working like fire within” (I.475-6) before she and her sisters torment him with scenes of his worst fears and causes for despair. To triumph over these attacks, Prometheus and Manfred both have to let it go: the past, the struggle, the violently-defended self. For Manfred, this means a move from the murky Gothic “witch-drama” he has been inhabiting towards the high equipoise of classical tragedy. As the play progresses, Manfred seems less of a Shakespearean and more of a Sophoclean or Senecan protagonist, quoting the last words of Nero to the Abbot—“It is too late” (III.i.98)—and thinking of the Roman Coliseum shortly before his death.

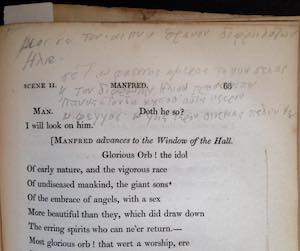

His final words, “Tis not so difficult to die” (III.iv.151), strike a distinctly classical note, the culmination of this trend. In partial confirmation, a contemporary reader of Manfred made marginal pencil notes in Greek in an 1817 copy of the second edition (Figure 1). The lines are from Sophocles’ Ajax, which our reader heard echoed in Manfred’s farewell address to the sun in Act III, scene two:

And you that drive your chariot up the steepOf Heaven, Lord Helios . . . you,Sweet gleam of daylight now before my eyes,Sun-God, splendid charioteer, I greet youFor this last time and never any more.5O radiance, O my home, and hallowed ground (II.845-6, 856-9)

Or, as Manfred says in part, “thou dost rise, / And shine, and set in glory. Fare thee well! / I ne'er shall see thee more” (III.ii.23-5). Taking his leave of nature and his place among the noble minds of classical antiquity, giving into or finally shedding his last infirmities, Manfred becomes a hero by losing himself, for good…and evil.