Editor’s note: The Kenyon Transcript

reproduces, in an attractive but unknown hand, most of the letter Dorothy Wordsworth wrote for William Johnson in late 1818. It is itself a letter, sent to “Miss Hutchinson” (probably Sara) in January 1819.

Though it omits introductory material that occupies more than a page in Dorothy’s own copy (DCMS 51); it also supplies roughly 300 words missing from DCMS 51 because of a tear in that manuscript’s last page. The Kenyon Transcript differs from DCMS 51 in punctuation, orthography, and other details. Certain spelling variations (e.g., “Seathwate,” “Scar Fell”) may be hearing errors rather than transcription errors; possibly the scribe worked from dictation. For particulars on this document, reasons for calling it the “Kenyon Transcript,” and ongoing research concerning it, please see the section appendix.

[in pencil and in a different hand:

101J. ? Dorothy Wordsworth]

October, 1818.

“I must inform you of a feat that Miss Barker and I performed

on Wednesday the 7th of this Month - I remained in Borrowdale after

Sir G. and Lady Beaumont and the Wilberforces were gone and

Miss Barker proposed to me that the next Day she and I should

go to Seathwate,

beyond the Black lead mines at the head of

Borrowdale and thence up a mountain called at the top

Ash Course – which we suppose may be a corruption

of Esk Hawes, as it is a settling between the mountains, over which

the people of Eskdale are accustomed to pass in going to Borrowdale,

and such settlings are generally called by the name of the Hawes

as Grisdale Hawes, Buttersmere

Hawes from the German word

Hals (the neck) – At the top of Ash Course – Miss Barker had

promised me that I should see a most magnificent prospect;

but we had some miles to travel to the foot of the mountain,

and accordingly we went thither in a Cart – Miss Barber,

her

maid and myself – we departed before nine oClock – The Sun

shone the sky was clear and blue, and light and shade fell in

huge masses upon the mountains, – the fields below glittered

with the dew where the beams of the Sun could reach them -

and every little stream tumbling down the hills seemed to add

to the chearfulness of the scene. – We left our Cart at

Stonethwaite,

and proceeded with a man to carry our

provisions, and a kind neighbor of Miss Barbers, a states-

man and Shepherd of the Vale, as our Companion & Guide. -

We found ourselves at the top of Ash Course, without a weary

limb, having had the fresh Air of Autumn to help us up by its

invigorating effects, and the sweet Warmth of the unclouded

sun to tempt us to sit and rest by the way. – From the top

of Ash Course, I beheld a prospect which would indeed have

amply repaid Me for a toilsome journey, if such it had been;

and a sense of gratitude for the continuance of that [end p 1. / 1r]

vigour of body which enabled me to climb the high mountain

as in the days of my youth, inspiring me with fresh chearfulness

added a delight – a charm to the contemplation of the magnificent

views before me which I cannot describe – Still less can I tell

you the glories of what we saw. – Three Views each distinct

in its kind, we saw at once – the Vale of Borrowdale – of

Keswick, of Bassenthwaite, of Skiddow, of Saddleback, Helvellyn,

numerous other mountains – and still beyond – the Solway

Frith and the Mountains of Scotland – Nearer to us on the

otherside and below us, were the Langdale Pikes – their own

Vale below them, Windermere, and far beyond after a long

Long distance – We saw Ingleborough in Yorkshire – But how

shall I speak of the peculiar deliciousness of the third Prospect!

At this time that was most favoured by Sun shine and shade -

The green Vale of Esk – deep and green, with its glittering serpent

stream was below us, and on we looked to the mountains near

the Sea – Black Comb, and others and still beyond to the Sea itself

in dazzling brightness. – At this same Station making what may

be called a 4th Division, turning round, we saw the mountains

of Wasdale in tumult, & Great Gavel though the middle of the

mountain was to us as its base, looked very grand – We had

attained the object of our journey; but our ambition mounted

higher – We saw the summit of Scar Fell,

as it seemed, very

near to us – We were indeed three parts up that mountain & thither

we determined to go, we found the distance greater than it had

appeared to us, but our Courage did not fail; however, when

we came nearer we perceived that in order to attain that

summit which had invited us forward – we must make

a great dip, and that the ascent afterwards would be

exceedingly steep and difficult, so that we might have been

benighted if we had attempted it, therefore unwillingly we gave

it up, and resolved, instead, to ascend another pike of the

same mountain, called the pikes and which I have since [end p. 2 / 2v]

found the measurers of the mountains estimate as higher than the

larger summit which bears the name of Scaw Fell, and where

the man is built, which we at the time considered as the point

of highest honour. – The Sun had never once been overshadowed

by a Cloud during the whole of our progress from the Center of

Borrowdale; at the summit of the pike there was not a breath

of air to stir even the papers which we spread out containing

our food – There we ate our dinner in summer warmth – and

the stillness seemed to be not of this world – We paused & kept

silence to listen and not a sound of any kind was to be heard

– We were far out of the reach of the Cataracts of Scaw Fell, & not an

Insect was there to hum in the Air – The Vales which I have

before described lay in view; – &, side by side with Eskdale,

we now saw the sister Vale of Donnerdale terminated by the Duddon

Sands - but the Majesty of the mountains below us and close to us

is not to be conceived – We now saw the whole mass of Great Gavel

from its base – the den of Wasdale, at our feet – the Gulph im-

-measurable – Grassmere and the other mountains of Crummock

–Ennerdale and its mountains – and the Sea beyond. – While we

were looking round after dinner our Guide said to us that we

must not linger long for we should have a storm – We looked

in vain to espy the traces of it – for mountains, Vales, and Sea were

all touched with the clear light of the Sun – “It is there,” – he said,

pointing to the Sea beyond Whitehaven, and, sure enough, we there

perceived a little Cloud or Mist, unnoticeable, but by a Shepherd

accustomed to watch all mountain bodings – We gazed all round

again, and yet again, fearful to lose the remembrance of what lay

before us in that lofty solitude, and then prepared to depart – Mean

-while the Air changed to cold, and we saw that tiny Vapour

swelled into mighty Masses of Cloud which came boiling over

the Mountains – Great Gavel, Helvellyn & Skiddew

were wrapped

in Storm; yet Langdale and the mountains in that quarter

were all bright with Sun shine – Soon the Storm reached us –

We sheltered under a Crag, and almost as rapidly as it had [end p.3 / 2r]

come, it passed away; and left us free to observe, the goings on of

storm and sunshine in other quarters

– Langdale had now its

share, and the Pikes were decorated by two splendid Rainbows

– Skidda also had its Rainbows; but we were truly glad to see

them and the clouds disappear from that mountain, as we knew

that Mr & Mrs Wilberforce and all their family (if they kept the intention

which they had formed when we parted the Night before) must certainly

be on Skaddow

at that very time, – and so it was – They were there

and had much more rain than we had – We indeed were hardly

at all wetted, and before we found ourselves again upon that part of

the mountain called Ash Course every Cloud had vanished from

every summit – Do not think we here gave up our Spirit

of Enterprize – No! I had heard much of the Grandeur of the Pass

of the Stye from Borrowdale to Wasdale, & of the Grandeur of the

view of Wasdale from Stye head the point from which Wasdale

is first seen in coming by the road from Borrowdale but though

I had been in Warsdale I had never entered the Dale by that road,

and had often lamented that I had not seen what was so much

talked of by Travellers. – Down to that Pass then (for we were

yet far above it) we bent our course by the side of Ruddle Gill

a very deep red chasm in the mountain, which begins at a

spring – that spring forms a stream which must at times be

a mighty Torrent, as is evident from the Channel which it has

wrought out thence by sprinkling Tarn to Stye-head and

there we sat and looked down into Wasdale. – We were now

upon Great Gavel, which rose high above us – opposite was

Scaw fell, and we heard the roaring of the stream from one of

the ravines of that mountain, which though the bending of Wasdale

head lay between us and Scaw Fell, we could look into, as it

were, and the depth of the ravine appeared tremendous – it

was black, and the Crags were awful – We now proceeded

homewards by Stye head Tarn along the road into Borrowdale

Before we reached Stonethwaite a few Stars had appeared,

and we travelled home in our cart by moonlight. I ought”

to [end p. 4 / 2v]

“to have described the last part of our ascent to Scaw Fell Pike – There

not a Blade of Grass was to be seen – hardly a cushion of Moss, and

that was parched and brown and only growing rarely between the

huge blocks and stones which cover’d the summit & lie in heaps

all round to a great distance – like Skeletons or bones of the Earth

not wanted at the Creation and there left to be covered by never

-dying lichens, which the Clouds and dews nourish and adorn

with Colours of the most varied and exquisite beau[ty]

and endless

in variety – No gems or flowers can surpass in colouring the beauty

of some of the masses of stone, which no human eye beholds,

except the Shepherd or Traveller is led thither by curiosity –

and how seldom must this happen! – The other eminence is

[that] which is visited by the adventurous Traveller; – and

[the Shep]herd has no temptation to go thither in quest of his

sheep; for on the Pike there is no food to tempt them. – [We]

certainly were singularly fortunate in the day; for when we

were seated on the summit, our Guide, turning his eyes

thoughtfully round said to us “I do not know that in my

whole life I was ever at any season of the Year so high

upon the mountains on so calm a day” – Afterwards, you

know we had the Storm which exhibited to us the grandeur

of earth and heaven commingled yet without terror – for we

knew that the Storm would pass away; for so our prophetic

Guide assured us - I forgot to tell you that I [esp]ied a Ship

upon the glittering Sea while we were looking over Eskdale –

– “Is it a Ship?” replied the Guide – “Yes it can be nothing else

dont

you see the shape of it? – Miss Barker interposed – “It

is a Ship, of that I am certain – I cannot be mistaken, I am

so accustomed to the appearance of Ships at Sea –” The Guide

dropped the argument; but a minute was scarcely gone

when he quietly said – “Now look at your Ship, it is now

a horse” – So indeed it was, with a gallant neck and head

– We laughed heartily, and I hope when I am again

inclined [end p. 5 / 3r]

inclined to positiveness I may remember the Ship and the

horse upon the glittering sea; and the calm confidence, yet

submission of our wise Man of the Mountains; who certainly

had more knowledge of Clouds than we, whatever might be

our knowledge of Ships. – To add to our uncommon performances

on this Day Miss Barker and I each wrote a letter from the top

of the Pike to our far distant Friend in South Wales – Sara Hutchinson

[Source and destination addresses written sideways in middle block of page]

Ellesmere January three 1819

Miss Hutchinson

[free?] Hindwell

Kenyon Radnor

I believe that you are not much acquainted with the

Scenery of this Country, except in the Neighbourhood of Grasmere,

your duties when you were a resident here, having confined

you so much to that one Vale; I hope, however, that my long

Story will not be very dull; and, even I am not without

a further hope, that it may awaken in you a desire to

spend a long holiday among the mountains, and explore

their recesses. –”

[end p. 6 / 3v]

II. Appendix: Ongoing Research on the Kenyon Transcript

Though known to scholars for decades, the document our edition calls the Kenyon Transcript remains mysterious. It has traditionally been catalogued as Dorothy’s “Letter to William Johnson,” but this designation is slightly misleading. First of all, Dorothy had no direct part in creating this document; indeed, there is no way to know if she even authorized it. Second, it was not mailed to William Johnson. It might have been mailed by him, or under his supervision, but that is a separate matter—see our conjectures in the following paragraphs. It seems best, all things considered, to emphasize that this is a copy of the Johnson letter, not the letter itself. It was a new document created with a different audience in mind.

We have limited information about the Kenyon Transcript’s making. The editors of William and Dorothy Wordsworth’s letters (second edition), Moorman and Hill, supposed that the copyist might be John Carter, William Wordsworth’s longtime clerk. However, handwriting comparison shows that this tentative attribution is incorrect. Ultimately, we do not know for certain who made the transcript or why, but we do have several clues.

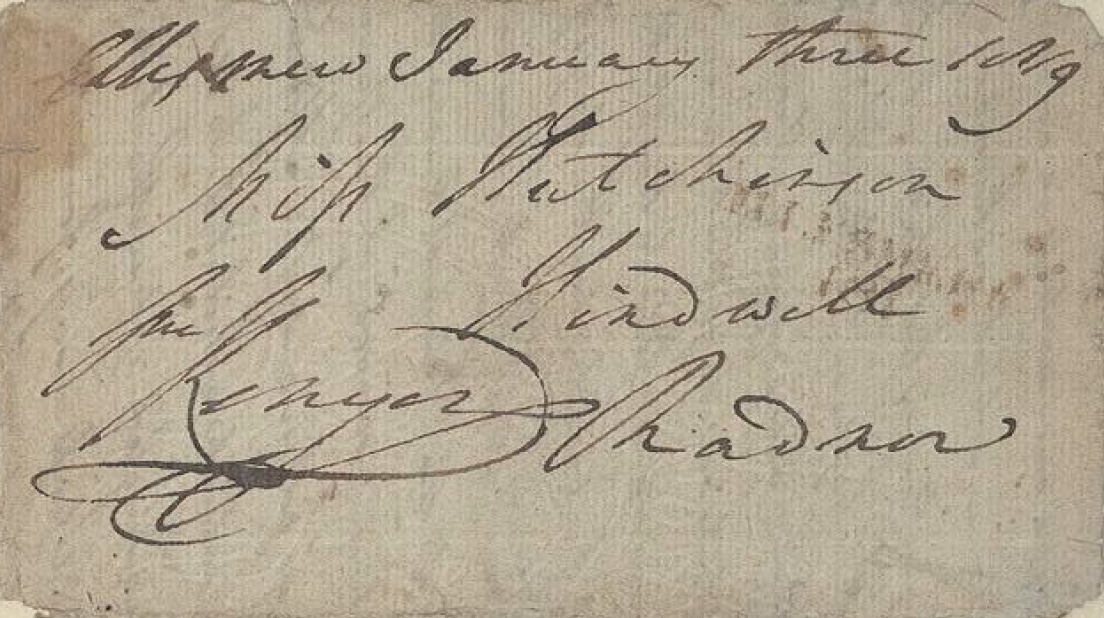

Though a letter, in some ways the Kenyon Transcript hardly seems like one: it includes no salutation, no signature, no epistolary framing at all aside from the fact that it is folded, addressed, and mailed. However, its address panel provides essential information (fig. 1). This panel features different handwriting from the body of the text (perhaps two different hands, in fact—one for the date line and the other for the address) and reads, “Ellesmere January three 1819 / Miss Hutchinson / Hindwell / Radnor.” Inserted on the left is “free[?] Kenyon,” which we take to be a parliamentary frank.

Figure 1. Detail from the Kenyon Transcript: the address panel directing the letter to “Miss Hutchinson.” The date line appears to be in one hand, the rest of the panel in another. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust).

Ellesmere is a market town in Shropshire. “Miss Hutchinson,” presumably, is Sara Hutchinson,

who is mentioned briefly in the transcription. Hindwell is the Hutchinson family farm in Radnorshire, South Wales.

Kenyon must be an MP or a peer, since he can post a letter without charge.

Summarizing, then, the Kenyon Transcript is a copy of Dorothy Wordsworth’s late-October 1818 letter to William Johnson that was made sometime between then and 3 January 1819. It was sent from Ellesmere to the Hutchinsons’ home in Radnor, some 47 miles away, under a certain Kenyon’s franking privilege. With these facts in mind, we can begin to reconstruct a possible history of the manuscript.

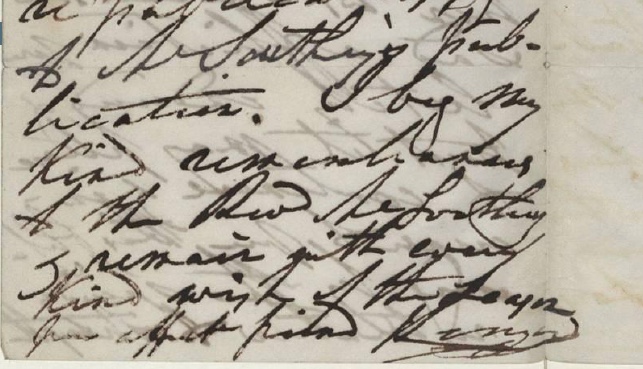

Who might Kenyon be? We propose that he is not, as some might suppose, John Kenyon, who appears frequently (in later years) in the Wordsworth family correspondence,

but rather George, Lord Kenyon, 2nd Baron Kenyon (1776–1855). Comparing the signature on the address panel with signatures on known letters of Kenyon’s, we find a close match (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Handwriting sample (including signature): letter from Lord Kenyon to Thomas Davies, 31 December 1842. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust).

Lord Kenyon, a lawyer and staunch promoter of the Church of England, was among other things a patron of educational reform. Kenyon might not have known Dorothy Wordsworth personally,

but he knew several of her friends. Consequently, unfolding the history of this transcript involves reconstructing a social network. The first character of note, naturally, is Johnson himself, the recipient of Dorothy’s original letter, who had become close to the Wordsworths during his 1811–1812 curacy in Grasmere. Johnson knew the Hutchinsons as well and might have wished to forward Dorothy’s account to Hindwell in any case. But what was Johnson’s connection, if any, to Kenyon? It turns out that Johnson was affiliated with an organization called the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales (hereafter “National Society”), founded in 1811, and that Kenyon was one of that organization’s vice presidents.

The National Society established schools employing the “Madras System” of mutual instruction pioneered by Dr. Andrew Bell, the next important character in our story. Bell and Kenyon were allies in their shared educational projects; and Bell, like Johnson, was a friend to Dorothy and William Wordsworth.

Indeed, it was Bell who hired Johnson away from Grasmere in January 1812 (supported by recommendations from the Wordsworths, though they were sorry to see him leave) to place him at the head of his model Central School in London. We also know that Bell was acquainted with the Hutchinsons as well as with Dorothy’s climbing companion, Mary Barker.

Robert Southey’s Life of the Rev. Andrew Bell indicates that, through Bell, William Johnson had met Lord Kenyon by at least August 1812, when Kenyon visited the Central School and “spoke most highly of Mr. Johnson’s superintendence.”

Over time, the three men had numerous interactions, including at meetings of the National Society.

In December 1818, not long after Dorothy’s Scafell Pike ascent, Johnson and Bell together visited Lord Kenyon at his seat, Gredington Hall, which was at Hanmer, near the Welsh-English border.

This could have been the occasion for Johnson to share with his two friends his remarkable letter from Dorothy Wordsworth—the moment also when the copy was made and sent to Hindwell. Why mail it from Ellesmere? This is also uncertain, but Ellesmere was just five miles from Gredington Hall, and Kenyon had established a school there. Possibly he, Bell, and Johnson went there for an inspection. Additional research may shed light on this question. In any case, we know that the document was mailed under Kenyon’s frank and that it originated at or near his home; this is our reason for calling it the Kenyon Transcript.

After visiting Kenyon at the end of 1818, Bell went straight to the Lake District, where he spent several days with the Wordsworths before taking lodgings at Keswick, near the Southeys.

William Johnson, too, visited the Wordsworths in January 1819, arriving just five days after Bell’s departure.

In short, Dorothy’s writing was probably circulating among this entire set of acquaintances—people who often communicated in person when not doing so by letter.

Several questions remain. Judging from the handwriting, Kenyon did not personally duplicate Dorothy’s remarkable ascent narrative, but who did? Not Bell or Johnson—their hands, too, were quite different. Possibly a clerk for one of these men was the scribe, or perhaps one of them wished to test an amanuensis.

Further research on Kenyon’s, Bell’s, or Johnson’s papers may yet allow us to identify the copyist with certainty. Even then, however, we shall be left with a puzzle, not knowing precisely why the copy was made and sent. One can, of course, imagine scenarios: for instance, Johnson, along with Bell and Kenyon, might suspect that the Hutchinson family would enjoy reading Dorothy’s account, especially because Sara was mentioned in it and had already been teased by “wish-you-were-here” notes written by Dorothy and Mary Barker at the Scafell Pike summit. (Indeed, the fact that the Kenyon Transcript begins without preamble makes one wonder if the recipient were already expecting it.) And then, Johnson might appreciate an excuse to reach out to his old friends, the Hutchinsons—at one point, Sara and others thought that Johnson might be a good match for her younger sister Joanna, who was also at Hindwell in January 1819.

Perhaps Johnson, still unmarried, held on to similar thoughts. Of course, this is all speculation.