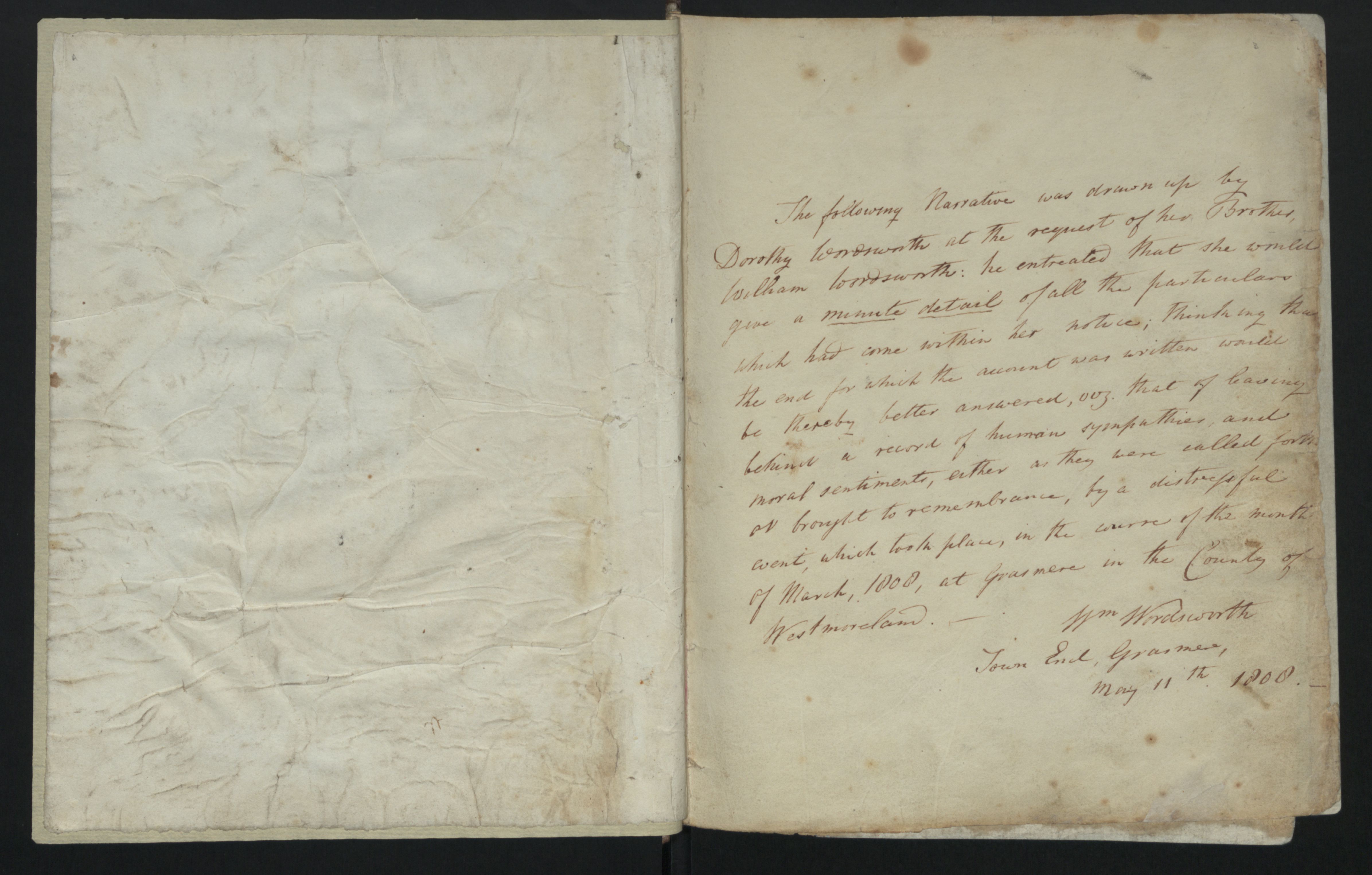

Figure 1. Inscription by William Wordsworth, signed “Town End, Grasmere, May 11th 1808”—his preface to DCMS 64. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

The following Narrative was drawn up by

Dorothy Wordsworth at the request of her Brother,

William Wordsworth: he entreated that she would

give a minute detail of all the particulars

which had come within her notice; thinking that

the end for which the account was written would

be thereby better answered, viz. that of leaving

behind a record of human sympathies, and

moral sentiments, either as they were called forth

or brought to remembrance, by a distressful

event, which took place, in the course of the month

of March, 1808, at Grasmere in the County of

Westmoreland. __.

Wm Wordsworth

Town End, Grasmere

May 11th, 1808.

A Narrative concerning George & Sarah

Green of the Parish of Grasmere

addressed to a Friend.

You remember a single Cottage at the foot of Blentern Gill_ it is the only dwelling on the western side ^of the upper reaches of the Vale of Easedale, and close under the mountain; a little stream runs over rocks and stones beside the garden

wall, after tumbling down the crags above:

I am sure you recollect the spot: if not, you remember George and Sarah Green who dwelt there. They left their home to go to

Langdale on the after noon of ^Saturday the 19th of March last: it was a very cold day with snow showers. They fixed upon that time for going because there was to be a Sale there;

in Langdale,

not that they wanted to make ⟨any⟩

purchases; but to mingle for the sake of mingling

a little amusement with the main object of the Woman’s journey, at least,

which was to see her Daughter who was in service there, and to settle with her Mistress about her continuing in her place. Accordingly, after having spent a few hours at the Sale, they went to the house where the young Woman lived, drank tea, and set off homewards

at about five o’clock, intending to cross right over the Fells, and drop down just upon their own Cottage; and they were seen, nearly at the top of the hill in their direct course, by some Persons in Langdale ^.

and were never more seen alive. It is supposed that soon afterwards they must have been bewildered by a mist, otherwise they might almost have reached their own Cottage at the bottom of the hill on the opposite side before daylight was entirely gone. They had left a Daughter at home, eleven years of age, with the care of five other Children younger than herself, the youngest an Infant at the breast; and they, poor Things! sate up till eleven o’clock expecting their Parents: they then went to bed, thinking that

they stayed all night in Langdale because of the weather. All next day they continued to expect them, and again went to bed as before; and at noon on Monday, one of the Boys went to the nearest house to borrow a Cloak, and, on being asked for what purpose, he replied that his Sister was going to Langdale, as he expressed it, “to lait their Folk,” meaning to seek their Father and Mother, who had not come home again, as they had

expected them, on Saturday. The Man of the house started up immediately, staying that “they were lost!”_ he spread the alarm through the neighborhood,

and many Men went out upon the hills to search; but in vain: no traces of them could be found; nor any tidings heard, except what I have mentioned, and that a Shepherd who had been upon the Mountains on Sunday morning had observed indistinct foot-marks of two Persons who had walked close together. Those foot-marks were now covered with fresh snow: the spot where they had been seen was at the top of Blea Crag above Easedale Tarn, that very spot where I myself had sate down <three>

six years ago, unable to see a yard before me, or to go a step further over the Crags. I had left W.illiam

at Stickell Tarn. A mist came on after I had parted with him, and I wandered long, not knowing whither. When, at last, the mist cleared away I found myself at the edge of the Precipice, and trembled at the Gulph below, which appeared immeasurable. Happily I had some hours of daylight before me, and after a laborious walk, I arrived at home in the evening. The neighbourhood of this Precipice had been

searched above and below, wherever foot could come; yet, recollecting my own dreadful situation, I could not help believing that George and Sarah Green were lying somewhere thereabouts. On Tuesday

as long as daylight lasted the search was continued. It was like a sabbath in the Vale: for all the Men who were able to climb the heights had left their usual work, nor returned to it till the Bodies of the unfortunate Pair were found, which was on Wednesday afternoon. The Woman was first discovered upon some rough ground just above the mountain enclosures beside Mill Beck, in Langdale, which is the next stream or torrent to that which forms Dungeon Gill Waterfall. Several Persons, the day before had been within a few yards of the spot where she lay; but her body had then been covered with snow, which was now melted. Her Husband was found at no great distance: he had fallen down a Precipice; and must have perished instantly, for his Skull was much fractured. It is supposed that his Wife had been by his side when he fell, as one of her shoes was left midway on the Bank above the precipice; afterwards (probably having stumbled over a crag) she had rolled many yards down the breast of the hill. Her body was terribly bruised. It is believed that they must have perished before midnight, their cries

or shrieks having been distinctly heard by two Persons in Langdale at about ten o’clock; but they paid

little attention to the ^sounds,

thinking that they came from some drunken People who had been at the Sale. At that time the wretched Pair ^had no doubt resigned all hope of reaching their own home, and were attempting to find a shelter any where; and, [two illegible deleted words] at the spot where they perished they might have seen the lights ^from the windows of that same house where their cries were actually heard. Soon after the alarm had been spread on Monday afternoon (and from that moment all were convinced of the truth; for it was well known that if the Mother had been alive she would have returned to her sucking Babe) two or three ^Women, Friends of the Family (Neighbours they called themselves; but they live at the opposite side of the dale) went to take care of the poor Children, and they found them in a wretched state “all crying together.” They had passed two whole days (from Saturday noon till Monday noon) without seeing any body, waiting patiently and without fear; and when the word came that their Father and Mother must have died upon the hills it was like a thunder- -stroke.

In a little time, however, they were somewhat pacified; and food was brought into the house; for their stock was almost exhausted, their Parents being the poorest People in the Vale, though they had a small estate of their own, and a Cow. This morsel of Land, now deeply mortgaged, had been in the

possession of the Family for many generations, and they were loth to part with it: consequently they had never had any assistance from the Parish. George Green had been twice married. By his former Wife he has left one Son and three Daughters; and by her who died with him four Sons and four Daughters, all under sixteen years of age. They must very soon have parted with their Land if they had lived: for their means were reduced by little and little till scarcely anything but the Land was left. The Cow was grown old; and they had not money to buy another; they had sold their horse; and were in the habit of carrying any trifles that they could spare out of house or stable to barter for potatoes or meal.

Luxuries they had none they never made tea, and when the Neighbours went to look after the Children they found nothing in the house but two boilings of potatoes, a very little meal, little bread, and three or four legs of lean dried mutton.

The Cow, at that time, did not give a quart of milk in the day. You will wonder how they lived at all; and indeed I can scarcely tell you. They used to sell a few peats in the summer, which they dug out of their own hearts’ heart, their Land; and the old Man (he was sixty five years of age) might earn a little ^ money by doing odd jobs for his neighbours; but it was not known till now (at least by us) how much distressed they must have been: for they were never heard to murmur or complain. See them when you would, both were chearful; and when they went to visit a Friend, or to a Sale they were decently dressed. Alas! a love of Sales had always been their failing, being perhaps the only publick meetings in this neighbourhood where social pleasure is to be had without the necessity of expending money, except, indeed, our annual Fair, and on that day I can recollect having more than once seen Sarah Green among the rest with her chearful countenance_ two or three little-ones about her; and their youngest Brother or Sister, an Infant, in her arms. These things are now remembered; and the awful event checks all disposition to harsh comments; perhaps formerly it might be said,

and with truth, the Woman had better been at home: but who shall assert that this same spirit which led her to come at times among her Neighbours as an equal, like them seeking society and pleasure, that this spirit did not assist greatly in preserving her ^ in chearful independence of mind through the many hardships and privations of extreme poverty? — Her Children, though very ragged, were always cleanly, and are as pure and innocent, and in every respect as promising Children as any I ever saw. The three or four latest born, it is true, look as if they had been checked in their grown for want of full nourishment; but none appear unhealthy except the youngest, a fair and beautiful Infant. It looks sickly, but not suffering: there is a heavenly patience in its countenance; and, while it lay asleep in its cradle three days after its Mother’s death, one could not look upon it without fanciful thoughts that it the Babe

had been sent into this life but to be her Companion, and was ready to follow her in tranquil peace. It would not be easy to give you an idea of the suspense and trouble in every face before the bodies were found: it seemed as if nothing could be

done, nothing else thought of, till the unhappyunfortunate

Pair were brought again to their own house: - the first question was “have you heard anything from the Fells?” On the second evening I asked a young Man, a next-door Neighbour of ours, what he should do tomorrow? “Why, to be sure, go out again,” he replied, and I believe that, though he left a profitable employment (he is by trade a Shoe-maker) he would have persevered daily if

the search had continued many days longer, even weeks. My Sister

Mary and I went to visit the Orphans on the Wednesday morning

: we found all calm and quiet_ two little Boys were playing about

on the floor_ the Infant was asleep; and two of the old Man’s up-grown Daughters wept silently while they pursued the business of the house: but several times one of them went out to listen at the door_ “Oh!” said they, “the worst for us is yet to come! we shall never be at rest till they are brought home; and that will be a dreadful moment.” _ Their grief then broke out afresh; and they spoke of a miserable time, above twenty years ago, when their own Mother and Brother died of a malignant fever_ nobody would come near them, and their Father was forced himself to lay his Wife in her coffin. “Surely,” they often repeated, “this is an afflicted

House! and indeed in like manner have I since frequently heard it spoken of by Persons less nearly concerned; but who still retain a vivid remembrance of the former affliction. It is, when any unusual event happens, affecting to listen to the fireside talk in our Cottages; you then find how faithfully the inner histories of Families, their lesser and greater cares, their peculiar habits, and ways of life are recorded in the breasts of their Fellow-inhabitants of the Vale; much more faithfully than it is possible that the lives of those who have moved in higher stations, and had numerous Friends in the busy world can be preserved in remembrance, even when their doings and sufferings have been watched for the express purpose of recording them in written narratives. I heard a Woman, a week ago, describe in as lively a manner the sufferings of George Green’s Family, when the former two Funerals went out of the house as if that trouble had been the present trouble. Among other things she related how Friends and Acquaintances, as is the custom here, when any one is sick, used to carry presents; but, instead of going to comfort the Family with their company and conversation, laid their gifts upon a Wall near the house, and watched till they were taken away.

It was, as I have said, on the Wednesday that we went to visit the Orphans. A few hours after we had left them John Fisher came to tell us that the men were come home with the ^dead

Bodies. A great shout had been uttered when they were found; but we could not hear it, as it was on the Langdale side of the Mountains. The Pair were buried in one Grave on the Friday afternoon. My Sister and I attended the Funeral. on the Friday afternoon. A great number of people of decent and respectable appearance were gathered together assembled

at the House. I went into the parlour where the two Coffins were placed with the elder of the Mourners sitting beside them: the younger Girls gathered about the kitchen fire, partly amused, perhaps, by the unusual sight of so many persons in their house: the Baby and its Sister Jane (she who had been left by the Mother with the care of the Family) sate on a little stool in the chimney-corner, and, as our Molly

said, after having seen them on the Tuesday, “they looked such an innocent Pair!” The young Nurse appeared to have touches of pride in her important office; for every one praised her for her notable management of the Infant, while they cast tender looks of sorrow

on

them both. The Child would go to none but her; and while on her knee its countenance was perfectly calm_ More than that: I could have fancied it to

it seemed to express even thoughtful resignation. Mary and I We

went out of doors, and were much moved by the rude and simple objects before us_ the noisy stream, the craggy mountain down which the old Man and his Wife had hoped to make their way on that unhappy night_ the little garden, untilled,_ with its box-tree and a few

peeping flowers! _ _ The furniture of the house was decayed and scanty; but there was one oaken Cupboard that was so bright with rubbing that it was plain it had been prized as an ornament and a treasure by the poor Woman then lying in her Coffin. Before the Bodies were taken up a threepenny loaf of bread was dealt out to each of the Guests: Mary

was unwilling to take hers, thinking that the Orphans were in no condition to give away any thing; she immediately, however, perceived that she ought to accept of it, and a Woman, who was near us, observed that it was an ancient custom now much disused; but probably, as the Family had lived long in the Vale, and had done the

like at funerals formerly, they thought it proper not to drop the custom on this occasion. There was something very solemn in t

The funeral procession ^was very solemn

– passing through the solitary valley of Easedale, and, altogether, I never witnessed a more moving scene. As is customary here, there was a pause, before the Bodies were borne through the Church-yard Gate, while part

of a psalm was sung, the men standing with their hats off heads uncovered

. In the Church the two Coffins were placed near the Altar, and the whole Family knelt on the ground floor

on each side of the Father’s Coffin, leaning over it. The eldest Daughter had been unable to follow with the rest of the Mourners, and we had led her back to the house before she got through the first field; the second fainted by the Grave side; and their Brother stood like a Statue of Despair, silent and motionless; the younger Girls sobbed aloud. Many tears were shed by persons who had known little of the Deceased; and all the people who were gathered together appeared to be united in one general feeling of sympathy for the helpless condition of the Orphans. After the Funeral the Family returned to their melancholy home. There was a Sale of the furniture on the Thursday following; and the next day the house was left empty and silent. A Lady from Ambleside had fetched the four little Boys on the day of the Funeral, to keep

them till it should be settled how they were to be disposed of. I saw them go past our door; they walked up the hill beside the Car in which they had been riding, and were chattering to their new Friend, no doubt well pleased with the fine(38)

Carriage. We had been told that she was going to take them and bring them up entirely herself; and my Sister came down stairs with tears of joy in her eyes. “Aye,” said our Neighbour, Peggy Ashburner “that Woman will win Heaven for protecting the Fatherless and Motherless;” and she, too, wept. Afterwards, however, we were undeceived, and were afraid that the Lady’s kindness was ill-judged, that it might unsettle them when they should be taken away from the grand house to a more humble dwelling. There are eight Children left under sixteen years of age. The eldest, a Girl, is in service, the second has lived with us more than half a year, and we had intended parting with her at Whitsuntide; but as soon as when

we heard of the loss of her Parents, we determined to keep her till she also is fit for service. The eldest, and only remaining Son of George Green by his first Wife will maintain one of the Boys and bring him up to his own trade; so that there remain five to be provided

for by the Parish; for, after the Father’s estate is sold and the Mortgage paid off, little or nothing will remain for his Family. It is the custom at Grasmere, and I believe in many other places, to let, as they call it, those Children who depend wholly upon the Parish, to the lowest Bidder, that is, to board them out to with Persons who will take them at the cheapest rate; and such as are the least able to provide for them properly are often the readiest Bidders, for the sake of having a little money coming in, though, in fact, the profit can be but very small: but they feel that they get something when the money comes, and do not feel exactly what they expend for the Children because they are fed out of the common stock. At ten years of age they are removed from their boarding-houses, and generally put out as Parish Apprentices, at best a slavish condition; but sometimes they are hardly used, and sometimes

all moral and religious instruction is utterly neglected. I speak from observation: for (I am sorry to say it)

that we have daily before our eyes an example of such neglect in the Apprentice of one of our near

Neighbours. From the age of seven or eight till he was eleven or twelve years old the poor Boy was employed in nursing his Mistress’s

numerous Children, and following them up and down the lanes. Sunday was no holiday for him; he was not, like others, dressed clean

on that day; and he never went to Church. I recollect, when I first came to live in this Country, a little more than eight years ago, observing his vacant way of roaming about. I remarked that there was an appearance of natural quickness with much good temper

in his countenance; but he looked wild and untutored: it was the face of a Child who had none to love him, and knew not in his heart what love was. He is now sixteen years old, and a strong, handsome-featured Boy; but though still the same traces of natural sense and good-temper appear, his countenance expresses almost savage ignorance, with bold vice. To this day he does not know a letter in a book; nor can ^he say his prayers, (as Peggy Ashburner expressed it strongly in speaking of him to Sara) “That poor Lad, if aught were to happen to him cannot bid God bless him!” _ His Master has a couple of crazy horses, and he now employs him in driving carrying slates to the next market_town, and, young as he is, he has often come home intoxicated. Sometimes, no doubt, the liquor is given to him; but he has more than once been detected in dishonest practices, probably

having been tempted to them by his

desire of obtaining liquor. I hope and believe that it does not often happen in this neighbourhood that Parish Apprentices are so grossly neglected as this Boy has been; and I need not give you my reasons for thinking that there is not another Family in Grasmere who would have done the like: nor even could it have been so bad even in this instance if the Boy had not come from a distant place, and consequently the Parish Officers are not in the way of seeing how he goes on; and I am afraid that, in such cases, they seldom take the trouble of making inquiries. You will not wonder, after what I have said, that we have been anxious to preserve these Orphans whom we saw so uncorrupted from the possibility of being brought up in such a manner, especially as there is

little possibility no likelihood that they would all have been quartered in their native Vale. From the moment we heard that their Parents were lost we anxiously framed plans for raising a little sum of money for the purpose of assisting the Parish in placing them with respectable Families; and to give them a little school-learning; and I am happy to tell you that others, at the same time,

were employing their thoughts in like manner; and our united efforts have been even more successful than we had dared to hope. It was a month yesterday since the sad event happened, and the Children are all settled in their several homes, ^in and all are in the Vale of Grasmere, except the eldest Boy, George, who is with his Brother at Ambleside. A Subscription has been made for the purpose of adding a little to the weekly allowance of the Parish, and to send them to School to apprentice the Boys, and to fit the Girls out for service; and, if there be any overplus, it is to be dealt out among them as they shall prove deserving, ^or according to their several needs

to set them forward in Life. It was

very pleasing to observe how much all, both rich and poor, from the very first appeared to be interested for the Orphans; and the Subscription_book, which we have seen this evening, is equally creditable to all ranks. With five guineas, ten guineas, three guineas, is intermingled a long list of shillings and sixpences, and even one threepence_ many of these ^smaller contributions

from labouring people and Servants. A committee of six of the neighbouring Ladies has been appointed to overlook

the Children and manage the funds. They had a meeting; and it was agreed that Mrs Wordsworth and Mrs King should engage with two Families who were willing to take three of the Orphans, much

less for the sake of profit than from the liking to Children in general, and from a wish to see these Children well taken care of, who had been left in circumstances of such peculiar distress. Another Lady had commission to conclude an engagement with a third Person who was willing to have the charge of the Infant and her Sister Jane. This

Lady, who

, I am sorry to say, cannot do a charitable action without the pleasure of being busy

, was galled that the whole concern had not been entrusted

to her guidance, and had before (without any authority) herself (though only recently come into the Country and having no connection with Grasmere) engaged to place all the children with an old Woman of in indigent circumstances, who was totally incapable of the charge. I will not blemish a narrative of events so moving, which have brought forward

so many kind and good feelings, by entering into the cabals and heart-burnings of Mrs North

. It is enough to say that Miss Knott, the Lady who has had the four Boys under her protection since

the day of their Parents’ Funeral, came to conduct the three youngest and their two Sisters to their new homes, attended by Mrs North Mrs -----

. George, the eldest, had been left at his Brother’s house

, where he is to remain. The Ladies called at our door in their way; and I was deputed to attend them in my Sister’s place

, John being very ill

, and his Mother could not unable to

leave him. I had the satisfaction of seeing all the five Children hospitably welcomed. It had been declared with one voice by the people of the Parish, men and women, that the Infant and her Sister Jane should not be parted. The Woman, who was to have the care of these two, was from home, and had requested a Neighbour to be in the way to receive them when they should come. She has engaged to instruct Jane in sewing and reading, being, according to the phrase in this Country “a fine Scholar”. Her Husband is living; but she has never had any Children of her own. They are in good circumstances, ^having a small estate of their own

, and her husband ^a Blacksmith by trade

, is a remarkably ingenious and clever Man; and she appears to be a kind-hearted Woman, which is shewn by her motives for taking these poor Children. She said to my Sister with great simplicity and earnestness “I should not have done it if we had not been such

near relations, for my Uncle George’s (namely the late George Green’s) first Wife and my Husband’s Mother were own Sisters,” from which odd instance of

relationship you may judge how closely the bonds of family connection are held together in these retired vallies. Jane and her Sister took possession of their new abode with the most perfect composure: Jane went directly to the fireside, and seated herself with the Babe on her knee: it continues to call out “Dad” and “Mam!” but seems not to fret for the loss of either: she has transferred all her affections to her Sister, and will not leave her for a moment to go to anyone else. This same little Girl, Jane, had been noticed by William and Mary ^ my Brother and Sister

some months ago, when they chanced to meet her in Easedale; at first not knowing who she was. They were struck, at a distance, with her beautiful figure and her dress, as she was tripping over the wooden bridge at the entrance of the Valley; and, when she drew nearer, the sweetness of her countenance, her blooming cheeks, her modest, wild and artless appearance quite enchanted them. William ^ My Brother could talk of nothing else for a long time after ^when

he came home, and he

minutely described her dress, a pink petticoat peeping under a long dark blue Cloak, which was on one side gracefully elbowed out, or distended as with a blast of wind by her carrying a basket on her arm

; and a pink bonnet tyed with a blue ribband, the lively colours harmonizing most happily with her blooming complexion. Part of this dress had probably been made up of her elder Sister’s cast-off cloaths: for they were accustomed to give to their Father’s Family whatever they could spare; often, I believe, more than they could well afford. Little did William ^ my Brother

at that time think that she was so soon to be called to such important duties; and as little that such a creature was capable of so much: for this was the Child who was left by her Parents at the head of the helpless Family, and was as a Mother to her Brothers and Sister when they were fatherless and motherless, not knowing of their loss. Her conduct at that time has been

the admiration of every body. She had nursed the Baby; and, without confusion or trouble, provided for the other Children who could run about: all were

kept quiet_ even the Infant that was robbed of its Mother’s breast. She had conducted other matters with perfect regularity, had milked the Cow at night and morning, wound up the clock, and taken care that the fire should not go out, a thingmatter

of importance in that house so far from any other, a tinder-box being a convenience which they did not possess. This little Girl I saw, as I have told you, take her place in her new home with entire composure: I know not indeed how to find a word sufficiently strong to express what I mean: it was a calmness amounting to dignity, which gave to every motion a perfect grace. We next went with two Boys in petticoats to a neat Farm_house: the Man and his Wife came down the lane a hundred yards to meet us, and would have taken the Children by the hand with almost parental kindness; but they clung to Miss Knott, the Lady who had fetched them from their Father’s Cottage on the day of the Funeral, & had treated them tenderly ever since. The younger sate

upon her lap while we remained in the house, and his Brother leaned against me: they continued silent; but I felt, some minutes before our departure, by the workings of his breast, that the elder Boy was struggling with grief, at the thought of parting with his old Friend. I looked at him, and perceived that his eyes were full of

tears: the younger Child, with less foresight, continued calm till the last moment, when both burst into an agony of grief. We have since heard that a slice of break and butter soon

quieted their distress: no doubt, the good Woman’s kind looks, though she gave to the bread and butter the whole

merit of consoling them, had had far more effect. She is by nature loving to Children, mild and tender_ inclining to melancholy, which has grown upon her since the sudden

Death of a Son, twenty years of age, who was not only the pride of his Father’s House, but of the whole Vale. She has other Children; but they are scattered abroad, except one Daughter, who is occasionally

with her, so that she has

of late spent many hours of the day in solitude; and her Husband yielded to her desire of taking these poor Orphans, thinking that

they might divert

her brooding thoughts. She has begun to teach them to read; and they have already won the hearts of the rest of the Family by their docility, and quite affectionate dispositions; and my Sister thought when she was at the house the other a few days ^ ago

, that she perceived a more greater of chearfulness

in the kind Woman’s manners than she had observed in her for a long time. They, poor Things! are perfectly contented; one of them was overheard saying to the other, while they were at play together, “My Daddy and Mammy’s dead

, but we will never go away frae this House.” We next went with the last remaining one of our charge, a Boy seven years old: his sorrow gathered while we were in the Chaise at the apprehension of parting from his Friend: he repeated more than once, however, that he was glad to go ^ to the house whither we were taking him; and Miss Knott, turning to me, said that

he had told her that

he should like to live with John Fleming (that was

the Man’s name) for he

had been kind to his Father and Mother, and had given them two sheep last year. She also related what seemed to me a remarkable proof of the Child’s sensibility. There had been some intention of fixing them

at another place, and he was very

uneasy at the thought of going thither, because, as he said, the Master of the House had had a quarrel with his Father. It appears that George Green and John Fleming

had had

a particular regard for each other; he was the Godfather of his Friend’s Daughter Jane, to whom he says he will give a fleece of wool every year to spin for ^ her own stockings, [illegible deleted word] and, from the day that the death of their Parents was known, he expressed a wish to have the care of little John. The manner in which he greeted the Boy, who could not utter a word for weeping, corresponded with this; he took hold of him, and patted his head as lovingly as if he had been his Grandfather, saying, “Never fear mun! thou shalt go upon the hills after the sheep; thou kens my sheep!” then (addressing himself to us) he went on_

“This little

Lad and his Brothers and Sisters used always to come to our Clippings, and they were the quietest Bairns that ever I saw, we

never had any disturbance among them.” Meanwhile poor John did not cease crying, and continued to weep as long as we remained in the house; but we have since seen him as happy and contented as plenty of food and kindness could make any Child. His Master is feeble and paralytic; but he spends most of his time out of doors, looking about

his own fields, or following the sheep. In these walks he had formerly no Companion but his Dog and his Staff: now, at night and morning

; before and after school hours, the Boy goes with him_ I saw them last night

on their return homewards; little John was running here and there, as sportive as a mountain lamb; for the Child may wander at will after his own fancies, and yet be a faithful attendant upon his Master’s course; for he creeps at a slow pace, with tottering steps. Much as the old Man delights in his new charge, his Housekeeper appears to have

little less pleasure in him: I found her last night knitting stockings for him out of

yarn spun from the Master’s fleeces, which is a gratuitous kindness, their allowance being half a crown weekly for

board and lodging. I said to her that I hoped the Boy was dutiful to her; and she replied that there was no need to give him any

correction, for he did nothing amiss, and was always peaceable, _ and happy too; and she mentioned

some little circumstances which proved

that she had watched him feelingly; among the rest, that on Saturday, his weekly holiday, he had gone with her and her Master to a mountain enclosure near Blentern Gill, where they had some sheep; they passed by his Father’s door, and the Child said to her (looking about, I suppose, in one of the Fields which had belonged to his Parents) “My Mother’s Ewe has got a fine Lamb.” The Woman watched his countenance, as she told us

, and could not perceive that he had any painful thoughts; but was pleased to see the new-dropped

Lamb and his Mother’s Ewe. The Ladies returned to Ambleside after we left John Fleming’s house. Mrs North

, it hurts me to say it, in her way to our door where we parted, appeared sullen and dissatisfied that she had not had the whole

management of the concern; but Miss Knott, who had a true interest in the Children’s well-doing

expressed great pleasure in what she had observed of the people who had taken charge of them, adding that she trusted the Family would prosper, for she had never seen or even heard

any set of Children that were so amiable as the four who had been under her roof: they were playful but not quarrelsome; and, though with hundreds of objects around them that were perfectly new and strange, they never had done any mischief, hardly had had need of a caution! The contentedness with which they have taken to their new homes proves that no wayward desires had been raised in them by the luxuries among which they had lived for the last three weeks; and we have been truly happy to perceive that our fears that this might happen were ill-grounded. Not only the Ladies of the Committee (except the one I have mentioned) but all the Persons

in Grasmere with whom I have conversed, approve entirely of the several situations in which the Orphans have been placed. Perhaps the irregular interference of Mrs

may have called forth a few unbecoming expressions of resentment from some of the Inhabitants of

of the Vale; but I must say that the general feelings have been purely kind and benevolent, arising from compassion for the forlorn condition of the Orphans and from a respectful regard for the memory of their Parents who with unexampled chearfulness, patience and self-denial, had supported themselves and their Family in extreme poverty; and have left in them a living testimony of their own virtuous conduct: for the Children’s manners (I again repeat it) are of one innocent, [illegible deleted word] and affectionate in a remarkable degree, so that each of them has already made Friends of [illegible deleted word]. I am almost afraid that you may have thought that

my account of the characters of the

Children is but a Romance, a dream of fanciful feeling proceeding in great measure from pity, pity producing love; yet I hope that the few facts which I have mentioned concerning them will partly illustrate what I have said. You will conclude with me that if the conduct of the Parents had not shewn an example of honesty, good-temper, and good manners these happy effects could not have followed: but I believe that the operation of their good example was greatly

aided by the peculiar situation of themselves and their Children. They lived in a lonely house where they seldom saw any body

. These Children had no Playfellows but their own Brothers and Sisters; and wayward inclinations or uneasy longings, where there was no choice of food or toys, no luxuries to contend for, could scarcely exist, they seeing nothing of such feelings in their Parents. There was no irregular variety in the earlier part of their infancy and childhood, and when they were old enough to be trusted from home they rarely went further than their own fields, except to go on errands; so that even then they would be governed by the sense of having a duty to perform. No doubt many Families are brought up in equal solitude and under the same privations; and we see no such consequences; and I am well aware that these causes have often a baneful effect if the Parents themselves be vicious; but such very poor People as in their situation most resemble these are generally in a state of dependence; and the chain which holds them back from dishonesty or any disgraceful conduct is by no means so strong. While George and Sarah Green held possession of the little estate inherited from their Forefathers they were in a superior station; and thus elevated in their own esteem

they were kept secure from any

temptation to unworthiness. The love of their few fields and their ancient home was a salutary passion, and, no doubt something of this must have spread itself

to the Children. The Parents’ cares and their chief employments were centred there; and, as soon as the ^ children could run about, even the youngest could take part in them while the elder would do this with a depth of interest which cannot be felt, even in rural life, where people are only transitory occupants of the soil on which they live. I need not remind you how much more such a situation as I have described as favourable to innocent and virtuous ^ habits and

feelings than that of those Cottagers who live in solitude and poverty without any out-of-doors employment. It is pleasant to me here to recollect how I have seen these very Children (with no Overlooker except when it was necessary for the elder to overlook the younger) busied in turning the peats which their Father had dug out of their

field near their own house,

and bearing away those which were dry (in burthens of three or four) upon their shoulders. In this way the Family were bound together by the same cares and exertions; and already one of them has proved that she maintained this spirit after she had quitted her Father’s Roof. The eldest, Mary, when only fourteen years of age, spared a portion of her year’s wages to assist them in paying for

the Funeral of

her Grandfather. She is a Girl of strong sense, and there is a thoughtfulness and propriety in her manners which I have seldom seen in one so young; this with great appearance of sensibility which shewed itself at the time of her Parents’ death, and since, in her [illegible deleted word]

anxiety for her Brothers and Sisters. Much, indeed, as I have said of the moral causes tending to produce that submissive, gentle, affectionate, and I may add useful character in these children, I have omitted to speak of the foundation of all, their own natural dispositions, or rather their constitutional temperament of mind and body. I am convinced from observation that there is in the whole Family a peculiar tenderness of Nature; perhaps inherited from their Father, whom I have several times heard speak of his own Family in a manner that shewed an uncommonly feeling heart; once especially: two or three years ago, when his Boy George had scalded himself and was lying dangerously ill, we met him in Easedale; and he detained us a full quarter of an hour while he talked of his

Child’s sufferings and his surpassing patience. I well remember the poor Father’s words “He never utters a groan_ never so much as says Oh Dear! but when he sees us grieved for him encourages us and often says “Never fear, I warrant you I shall get better again.” These circumstances and many more which

I do not so distinctly recollect the old Man repeated with tears streaming down his cheeks; yet we often saw a smile of pride in his face while he spoke of the Boy’s fortitude and undaunted courage. I have said that George Green had been twice married, and that his Son and Daughters by the first Wife are in a respectable condition of life; but he had not only brought up thus far his own large Family; but also two Children, a Son and a Daughter, whom his Wife had borne before marriage. He received eighteen pence weekly towards the maintenance of each, and brought them up as his own Children. I do not know what Sarah Green’s general conduct before marriage may have been, further than that she was a young

Woman when these Children were born. She had been a Parish Apprentice and therefore, probably, a neglected Child, and, having had the merit of conquering her failings, she for that cause may perhaps be entitled to a higher praise than would have been her due if she had never fallen. Her conduct as a Wife and a Mother were was

irreproachable. Though she could not read herself, she had taught all her Children,

even to the youngest but one, to say their prayers, and had encouraged in them a love and respect for learning; the elder could read a little though none of them had been at school more than a single month in the course of the last summer

, except Sally whose schooling was paid for by a Lady ^ in whose house she had been who had had her in her house a short time. Since their Parents’ death two of the Boys have gone regularly to school; and George, the eldest, takes particular delight his Book. The little Fellow used to lie down upon the carpet in Miss Knott’s parlour poring over the

“Reading-made-Easy” by firelight and would try to spell words out of his own head. The Neighbours say that George and Sarah Green had but

one fault; they were rather “too Stiff,” unwilling to receive favours; but the “keenest Payers,” always in a hurry to pay when they had money, and for this reason those who knew them best were willing to lend them a little money to help them out of a difficulty; yet very lately they had sent to the shop for a loaf of bread, and because the Child went without ready money the Shopkeeper refused to let them have the bread. We, in our connection with them have had one opportunity of remarking (alas! we gained our knowledge since their death) how chearfully they submitted

to a hard

necessity, and how faithful they were to their word. Our little Sally wanted two shifts: we sent to desire her Mother to procure them; the Father went the very next day to Ambleside to buy the cloth, and promised to pay for it in three weeks. The shifts were sent to Sally without a word of the difficulty of procuring them, or anything like a complaint. After her Parent’s death we were very sorry (knowing now so much of their extreme poverty) that we had required this of them, and on asking whether the cloth was paid for (intending ourselves

to discharge that debt) we were told by one of the Daughters that she had been to the Shop purposely to make the enquiry, and found that, two or three days before the time promised, her Father had himself gone to pay the money. Probably if they had lived another week longer they must have carried some article of furniture out to barter for that week’s provisions. I have mentioned how very little food there was in the house at that time_ there was no money,_not even a single halfpenny!_ The pair had each threepence in their pockets when they were found upon the mountains.

With this eagerness to discharge their debts they combined an their unwillingness to receive favours ^was so great that the Neighbours called it pride,

or as I have said “stiffness”. Without this pride (for we must call it so) what could have supported them? Their chearful hearts would probably have sunk, and even their honesty might have slipped from them. The other day I was with Mary Cowperthwaite; the Widow of one of our Statesmen; she began to talk of George and Sarah Green, who, she said, “had made a hard struggle; but they might have done better if they had not had quite so high a spirit.” She then told me that

she had called at their house last summer to look after some cattle that she had put upon George Green’s Land. Sarah brought out a phial [illegible deleted word] with ^ containing

a little gin, ^ in it

, poured out a glass of it

, and insisted that her visitor should drink, saying, “I should not have had it to offer you if it had not been for that little thing,” pointing to the Cradle, “it has been badly in its bowels,

and they told me that a little common gin would mend it.” Mrs. Cowperthwaite took the gin, much against her mind, on condition that Sarah Green should drink tea with her the next Sunday, which she promised to do, and Mary Cowperthwaite told her that that [sic] she would have a bundle of old

cloaths ready for

her to take home with her

; however she did not go on the Sunday afternoon; and Mrs. Cowperthwaite

says that she believes that the fear of receiving this gift had

prevented her: for she had never seen her at her house afterwards, though the promise was made many

months before her Death. It is plain that the poor Woman had had no secret cause of offence against her intended ^ who would have been

benefactress; for on the day on which she died she had followed Mrs Cowperthwaite’s Son all up and down at the Sale withersoever he turned

, urging him to request his Mother to take her Daughter Mary as a Servant, she being then in service at a publick House, a situation which she did not altogether approve of. Within the last few days of her Sarah Green’s

life her thoughts had been very much occupied with her Children. On the day before she died she went to Ambleside with butter X to sell, and talked with our neighbour, John Fisher, about her Daughter Sally, who is with us

, and said she should “think of him,” that is, be grateful to him as long as she lived for having been the means of placing Sally at our house, regretted that we could not keep her longer

; but, in her chearful way, ended with “we must do as

well as we can.” On her road home

she fell into company

with another Person, and talked fondly of her Infant, who, she said, was “the quietest creature in the world. You will remember that the object of her last fatal journey was to look after her Daughter who was a Servant at a house in Langdale; and that while she was at the Sale she took unwearied pains about another (namely her eldest by her husband) – Poor Woman! she is now at rest: I have seen one of her Sons playing beside her grave; and all her Children have taken to their new homes, and are chearful and happy. In the night of her anguish could if she could but have had a foresight of the kindness that would be shewn to her Children, what a consolation would it have been to her

! With her many cares and fears for her helpless Family she must, at that time, have mingled some bitter self-reproaches for her boldness in venturing over the Mountains: for they had asked two of the Inhabitants of the Vale to accompany them, who refused to go by that way on account of the bad weather, and she laughed at them for being cowardly. It is now said that her Husband was always fond of doing things that nobody else liked to venture upon, though

he was not strong, and had lost one eye by an accident. She was healthy and active, one of the freshest Women of her years that I ever noticed, and walked with an uncommonly vigorous step. She was forty-five years of age at her Death. Her Husband’s Daughters speak of their Mother-in-law

with great respect: she always, whenever they went to their Father’s house, strove to make it as comfortable to them as she could; and never suffered her own Children to treat them unbecomingly. One of the young Women, who has long been a Servant in respectable Families in the neighbourhood, told us with tears in her eyes, that once, not very long ago, she went to Blentern Gill, not intending to stay all night, and when she took up her Cloak to go away her Mother said to her, “What you cannot stop in such a poor House!” The Daughter after this had not the heart to go away

, and laid aside her Cloak. Another time when the chearful Creature was pressing her to stay longer she said to her, “What Aggy, to be sure we have no tea; but we have very good tea-leaves.” By the bye, those tea-leaves came

from our house: one of the little Girls, our own Sally or another, used to come to fetch them_ two long miles!_I well recollect (it is now five or six years ago) how we then were struck with the pretty simple manners of these little-ones. I have spoken much of the interest which we take in the younger Children of George Green, and I may add that the same constitutional tenderness appears even in a much more marked degree in the elder part of the old Man’s

Family: we have observed in them many proofs of tender and even delicate sensibility as well as of strong and deep feeling_ so much respect for every thing that had belonged to the Deceased_ the few cloaths, the furniture, and the old Family Dwelling. In no situation of life did I ever witness marks of more profound distress than appeared in them immediately after the death of their Father and Mother; for they

called her Mother

. The eldest Son, on returning to his own house at Ambleside, after having been at Grasmere on the day when it was first known that they were lost, was unable to lift the latch of his own door, and fainted on the threshold, and might have perished also if his Wife had not happened to hear

him; for it was a bitter cold

night. I may say with the Pedlar in the “Recluse” __ __“I feel The story linger in my heart, my memory “Clings to these is poor people and I fear I poor woman and her family poor Woman & her Family

^ and I fear I

have spun out of my narrative to a tedious length. I cannot give you the same feelings that I have of

them as neighbours and fellow-inhabitants of this Vale; therefore what is in my mind a full and living picture will be to you but a feeble sketch. You cannot, however, but take part in my earnest prayer that the Children may grow up, as they have begun, in innocence, and virtue

, and that the awful end of their Parent may hereafter be remembered by them in such a manner as to implant in their hearts a reverence and sorrow for them that

may purify their thoughts and make them wiser and better. There is, at least, this consolation, that the Father and Mother have been preserved by their untimely end from that dependence which they dreaded. The Children are likely to be better

instructed in reading and writing, and may acquire knowledge which their Parents’ poverty would have kept them out of the way of attaining: and perhaps, after the land had been sold the happy chearfulness of George and Sarah Green might have forsaken them, and their latter days have been tedious and melancholy.

Dorothy Wordsworth

Grasmere May 4th 1808.

Page 1st_“Blentern Gill“ _Probably Blind Tarn Gill; as there is ^ a swamp

upon the mountain a swamp

out of which the little stream runs. This swamp is shaped like a Tarn and might (if it were worth while) with very little trouble be formed into a small Lake or Tarn.

Page 38_ “She went to Ambleside with butter” I myself met her and desired that

she would leave one pound (of the four which she had in her Basket)

at our house. Those four Pounds of Butter must have been the produce of at least, a fortnights’ careful savings, as the cow gave very little milk at that time. She had not left a morsel at home for their own use, a striking proof of her resolute

self-denial. I have said that they never had any luxuries. My account of the stock of provisions in the house at the time of her Death is literally true. If I were to enumerate all the things

that were wanting even to the ordinary supply of a very

poor house what

a long list it would be! There was no sugar in the house_ no salt.

I ought to have mentioned that George Green’s debts, save the Mortgage on his Estate, were very small and few in number. The household goods sold for their full worth, perhaps more_The Cupboard of which I have mentioned was bought for fourteen shillings and sixpence_ an oaken Chest for twenty four shillings, and their only Feather Bed for three pounds. The Cow sold for but twenty four shillings, and I believe that was its full value. These articles which I have mentioned were the most valuable of their moveable possessions. We purchased the poor Woman’s Churn & milking Can for which we gave eight shillings and sixpence.

An affecting circumstance is related of Sarah Green’s natural Daughter, with whom she parted on the Saturday evening

, after having drunk tea with her Mistress. The Girl did not hear of the melancholy event till Monday Evening, and she was with difficulty kept from going herself over the Mountains, though night was coming on. In her distraction she thought that she surely could find them. I do not speak of this as denoting any extraordinary sensibility; for I believe

most young persons in the like dreadful situation would have felt in

in the same manner_ and perhaps old ones too_for the circumstance reminds me of Mary Watson, then 73 years of age, who when her Son was drowned in the lake six years ago, walked up and down upon the shore entreating that she might be suffered to go in one of the Boats for though others could not find him_ she said “Do let me go I am sure I can spy him!” I never

shall forget the agony on her face_ without a tear. She looked eagerly towards the Island near the Shore of which her Son had been lost, and wringing her hands, said, while I was standing close to her, “I was fifty years old when I bore him, & he never gave me any

sorrow till now.” The death of this young Man, William Watson, caused universal regret in the Vale of Grasmere. He was drowned on a fine summer’s Sunday afternoon having gone out in a Boat with some Companions to bathe. His Body was not found till the following morning though the spot where he had sunk was exactly known. All nightboats were on the water with lights, and it was a very

dismal sight from our windows. He could not swim & had got into one of the well-springs of the lake, which are always very deep.

The end of poor Mary Watson herself was more tragical than that of the young man. ^ A few years ago She was murdered in her own cottage by a poor maniac, her own son, with whom she had lived fearlessly though every one in the vale had apprehensions for her_ The estate at her death fell to her grandson_ He had been sent to Liverpool to learn a trade, came home a dashing fellow, [illegible word] all his property took to dishonest practices, & is now under sentence of transportation.