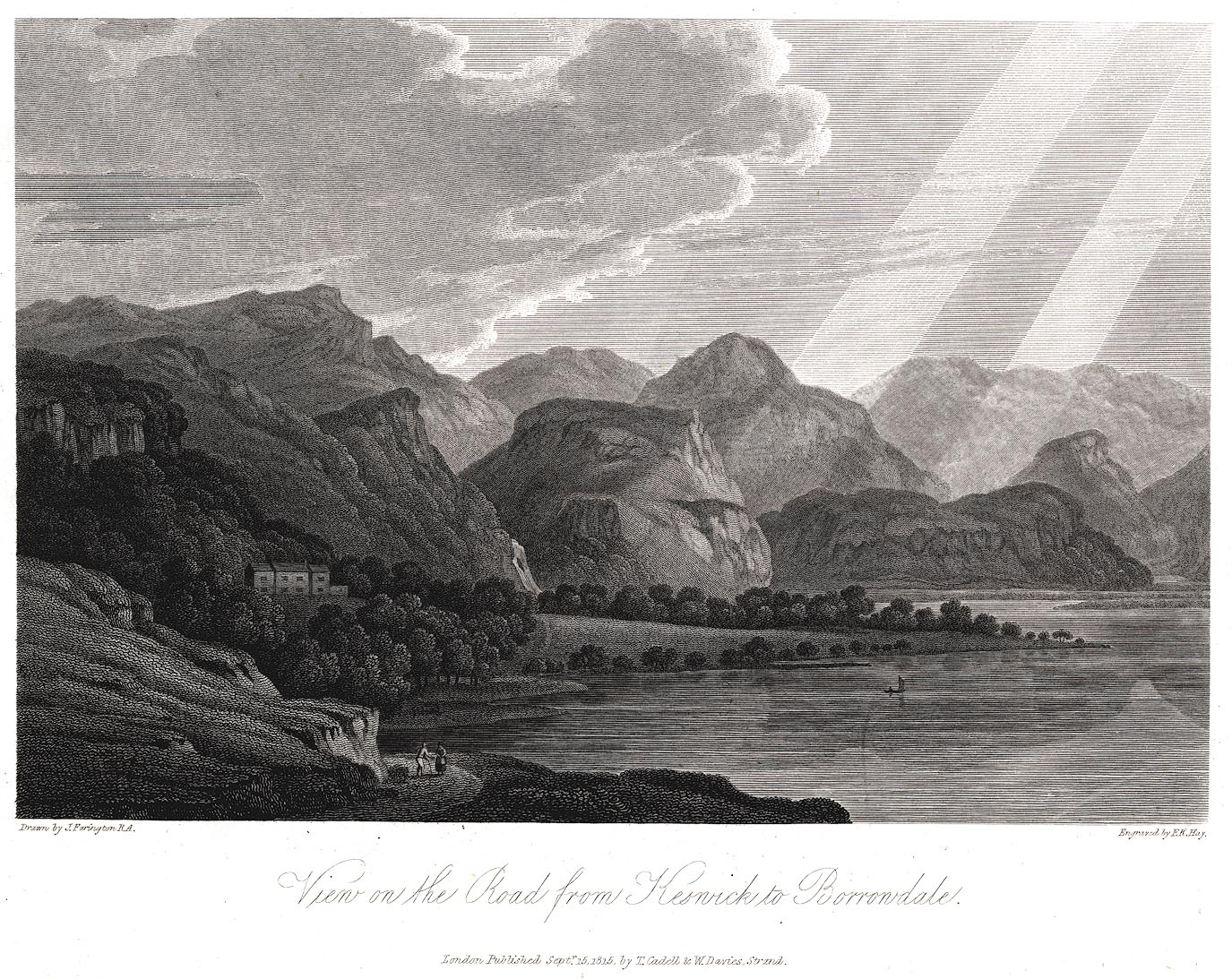

Sir George and Lady Beaumont spent a few days with us lately, and I accompanied them to Keswick. Mr. and Mrs. Wilberforce and their family happened to be at Keswick at the same time, and we all dined together in the romantic Vale of Borrowdale, at the house of a female friend, Miss Barker, an unmarried lady, who, bewitched with the charms of the rocks, and streams, and mountains of that secluded spot, has there built herself a house,

and, though she is admirably fitted for society, and has as much enjoyment when surrounded by friends as any one can have, her chearfulness has never flagged, though she has lived more than the year round alone in Borrowdale, at six miles distance from Keswick, with bad roads between.

You will guess that she has resources within herself; such indeed she has. She is a painter and labours hard in depicting the beauties of her favourite vale; she is also fond of music and of reading; and has a reflecting mind: besides (though before she lived in Borrowdale she was no great walker) she is become an active climber of the hills, and I must tell you of a feat that she and I performed on Wednesday the 7th of this month. I remained in Borrowdale after Sir George and Lady Beaumont and the Wilberforces were gone, and Miss Barker proposed

that the next day she and I should go to Seathwaite beyond the black lead mines

at the head of Borrowdale, and thence up a mountain called at the top Ash Course, which we suppose may be a corruption of Esk Hawes, as it is a settling between the mountains over which the people are accustomed to pass between Eskdale and Borrowdale; and such settlings are generally called by the name of “the Hawes”—as Grisedale Hawes, Buttermere Hawes—from the German word Hals (neck).

At the top of Ash Course Miss Barker had promised I should see a magnificent prospect; but we had some miles to travel to the foot of the mountain,

and accordingly went thither in a cart—Miss Barker, her maid, and myself.

We departed before nine o’clock. The sun shone; the sky was clear and blue; and light and shade fell in masses upon the mountains; the fields below glittered with the dew, where the beams of the sun could reach them; and every little stream tumbling down the hills seemed to add to the chearfulness of the scene.

We left our cart at Seathwaite

and proceeded, with a man to carry our provisions, and a kind neighbour of Miss Barker’s, a statesman and shepherd of the vale, as our companion and Guide.

We found ourselves at the top of Ash Course without a weary limb, having had the fresh air of autumn to help us up by its invigorating power, and the sweet warmth of the unclouded sun to tempt us to sit and rest by the way. From the top of Ash Course we beheld a prospect which would indeed have amply repaid me

for a toilsome journey, if such it had been; and a sense of thankfulness for the continuance of that vigour of body, which enabled me to climb the high mountain, as in the days of my youth, inspiring me with fresh chearfulness, added a delight, a charm to the contemplation of the magnificent scenes before me which I cannot describe. Still less can I tell you the glories of what we saw.

Three views, each distinct in its kind, we saw at once: the vale of Borrowdale, of Keswick, of Bassenthwaite—Skiddaw, Saddleback, Helvellyn, numerous other mountains, and, still beyond, the Solway Frith,

and the Mountains of Scotland.

Nearer to us on the other side, and below us, were the Langdale Pikes—their own Vale below them, Windermere—and, far beyond, after a long long distance, Ingleborough in Yorkshire. But how shall I speak of the peculiar deliciousness of the third prospect! At this time that was most favoured by sunshine and shade. The green Vale of Esk—deep and green, with its glittering serpent stream was below us; and on we looked to the mountains near the sea—Black Comb and others—and still beyond, to the sea itself in dazzling brightness.

Turning round we saw the mountains of Wasdale in tumult; and Great Gavel, though the middle of the mountain was to us as its base, looked very grand.

We had attained the object of our journey; but our ambition mounted higher. We saw the summit of Scaw Fell, as it seemed, very near to us: we were indeed, three parts up that mountain; and thither we determined to go. We found the distance greater than it had appeared to us; but our courage did not fail; however, when we came nearer we perceived that, in order to attain that summit, we must make a great dip,

and that the ascent afterwards would be exceedingly steep and difficult, so that we might have been benighted if we had attempted it; therefore, unwillingly, we gave it up, and resolved, instead, to ascend another point of the same mountain, called the Pikes, and which, I have since found, the measurers of mountains estimate as higher than the larger summit which bears the name of Scaw Fell,

and where the Stone Man is built, which we, at the time, considered as the point of highest honour.

—The Sun had never once been overshadowed by a cloud during the whole of our progress from the centre of Borrowdale; at the summit of the Pike there was not a breath of air to stir even the papers which we spread out containing our food. There we ate our dinner in summer warmth; and the stillness seemed to be not of this world. — We paused, and kept silence to listen, and not a sound of any kind was to be heard. — We were far above the reach of the cataracts of Scaw Fell; and not an insect was there to hum the air. The vales before described lay in view; and, side by side with Eskdale, we now saw the sister Vale of Donnerdale terminated by the Duddon Sands. But the majesty of the mountains below and close to us, is not to be conceived. We now beheld the whole mass of Great Gavel from its base—the Den of Wasdale at our feet, the gulph immeasurable—Grassmire

and the other mountains of Crummock—Ennerdale and its mountains; and the sea beyond.

While we were looking round after dinner our guide said to us that we must not linger long, for we should have a storm. We looked in vain to espy the traces of it; for mountains, vales, and sea were all touched with the clear light of the sun. “It is there,” he said, pointing to the sea beyond Whitehaven; and, sure enough, we there perceived a light cloud, or mist, unnoticeable but by a shepherd, accustomed to watch all mountain bodings.

We gazed around again and yet again, fearful to lose the remembrance of what lay before us in that lofty solitude; and then prepared to depart. Meanwhile the air changed to cold, and we saw the tiny vapour swelled into mighty masses of cloud which came boiling over the mountains. Great Gavel, Helvellyn, and Skiddaw were wrapped in storm; yet Langdale, and the mountains in that quarter were all bright with sunshine. Soon the storm reached us; we sheltered under a crag;

and, almost as rapidly as it had come, it passed away, and left us free to observe the goings-on of storm and sunshine in other quarters. Langdale had now its share, and the Pikes were decorated by two splendid rainbows; Skiddaw also had its own rainbows, but we were truly glad to see them and the clouds disappear from that mountain, as we knew that Mr. and Mrs. Wilberforce and their family (if they kept the intention which they had formed when they parted the night before)

must certainly be upon Skiddaw at that very time—and so it was. They were there, and had much more rain than we had; we, indeed, were hardly at all wetted; and before we found ourselves again upon that part of the mountain called Ash Course every cloud had vanished from every summit.

Do not think we here gave up our spirit of enterprise. No! I had heard much of the grandeur of the view of Wasdale from Stye Head, the point from which Wasdale is first seen in coming by the road from Borrowdale; but though I had been in Wasdale I had never entered the dale by that road, and had often lamented that I had not seen what was so much talked of by travellers. Down to that pass (for we were yet far above it) we bent our course by the side of Ruddle Gill,

a very deep red chasm in the mountains, which begins at a spring—that spring forms a stream, which must, at times, be a mighty torrent, as is evident from the channel which it has wrought out thence by Sprinkling Tarn to Stye head;

and there we sate and looked down into Wasdale. We were now upon Great Gavel which rose high above us. Opposite was Scaw Fell, and we heard the roaring of the stream, from one of the ravines of that mountain, which, though the bending of Wasdale Head lay between us and Scaw Fell, we could look into, as it were; and the depth of the ravine appeared tremendous; it was black, and the crags were awful.

We now proceeded homewards by Stye head Tarn along the road into Borrowdale.

Before we reached Seathwaite

a few stars had appeared, and we travelled home in our cart by moonlight.

I ought to have described the last part of our ascent to Scaw Fell Pike. There, not a blade of grass was to be seen—hardly a cushion of moss, and that was parched and brown; and only growing rarely between the huge blocks and stones which cover the summit and lie in heaps all round to a great distance, like skeletons or bones of the earth not wanted at the creation, and there left to be covered with never-dying lichens, which the clouds and dews nourish; and adorn with colours of the most vivid and exquisite beauty, and endless in variety.

No gems or flowers can surpass in colouring the beauty of some of these masses of stone, which no human eye beholds, except the shepherd is led thither by chance or the traveller by curiosity; and how seldom must this happen! The other eminence

is that which is visited by the adventurous traveller, and the shepherd has no temptation to go thither in quest of his sheep; for on the Pike there is no food to tempt them.

We certainly were singularly fortunate in the day; for when we were seated on the summit our Guide, turning his eyes thoughtfully round, said to us, “I do not know that in my whole life I was ever at any season of the year so high up on the mountains on so calm a day.” Afterwards, you know, we had the storm which exhibited to us the grandeur of earth and heaven commingled, yet without terror; for we knew that the storm would pass away; for so our prophetic Guide assured us. I forgot to tell you that I espied a ship upon the glittering sea while we were looking over Esk dale. “Is it a ship?” replied the Guide. “A ship! yes it can be nothing else, don’t you see the shape of it?” Miss Barker interposed, “It is a ship,

of that I am certain—I cannot be mistaken, I am so accustomed to the appearance of ships at sea.” The Guide dropped the argument; but a minute was scarcely gone when he quietly said, “Now look at your ship, it is now a horse.” So indeed it was, with a gallant neck and head. We laughed heartily, and I hope when I am again inclined to positiveness I may remember the ship and the horse upon the glittering sea; and the calm confidence, yet submission of our wise Man of the Mountains, who certainly had more knowledge of clouds than we, whatever might be our knowledge of ships.

—To add to our uncommon performances on this day Miss Barker and I each wrote a letter from the top of the Pike to our far distant friend in South Wales—Sara Hutchinson.

I believe that you are not much acquainted with the Scenery of this Country, except in the Neighbourhood of Grasmere, your duties when you were a resident here, having confined you so much to that one Vale; I hope, however, that my long Story will not be very dull; and even I am not without a further hope, that it may awaken in you a desire to spend a long holiday among the Mountains, and explore their recesses.