I: Contexts

A. Return to the Lakes

B. Walking in the Lakes

C. Writing for the Journals

D. Publication and Reception History of the Journals

II: Textual and Editorial Issues

I. Contexts

In this section, we present the entirety of Dorothy Wordsworth’s first Grasmere journal notebook, DCMS 20. This notebook includes entries for 172 days, from 14 May to 22 December 1800, as well as other miscellaneous material Dorothy copied into the pages. The contents of this single notebook are reproduced through diplomatic transcription, meaning that we record as closely as possible the appearance of the text in the original manuscript. Thus, we preserve all of Dorothy’s original spellings and abbreviations and her marks of revision (corrections, cancellations, substitutions) as well as, where possible, other nonlinguistic marks (such as lines she draws between some journal entries), in addition to her line and page breaks. There are multiple reasons for keeping editorial intervention to a minimum. By copying Dorothy’s words and punctuation as they appear on the page, we make her compositional processes more available for interpretation—processes that are often obscured in regularized edited versions of the journal. For example, her use of contractions, abbreviations, and ampersands suggests that she wrote in haste. For similar reasons, we include all of her journal entries rather than editorial selections. By reviewing each entry, it is possible to follow her daily routines as she recorded them, over a six-month period, without focusing on exceptional entries or events. The preservation of line breaks reminds readers of the diplomatic transcription of the small size of the notebook Dorothy used and the short nature of the entries themselves. In sum, this straightforward presentation supports understanding of the material practices and structures within which Dorothy wrote all four notebooks of her now-famous Grasmere journals.

A. Return to the Lakes

Dorothy and William Wordsworth were born (in 1771 and 1770, respectively) in Cockermouth, Cumberland (now Cumbria), about 25 miles northwest of Grasmere. They and their three brothers were separated after the death of their mother in 1778: Dorothy was sent to live with her mother’s cousin in Halifax, West Yorkshire (and later with other relatives), while William was sent with his brother Richard to Hawkshead Grammar School, six miles due south of Grasmere (see fig. 3). William and Dorothy did not see each other again for nine years. They were together briefly in 1787, before William went to Cambridge, and ultimately, they lived together in various residences from 1795 onward, first in Racedown, Dorsetshire, and then in Alfoxden, Somerset, southwest of Bristol. On 17 December 1799 (after a cold winter spent in Goslar, Germany), brother and sister moved to Town End, Grasmere, adopting the home now known as Dove Cottage. They would live in Grasmere and the nearby village of Rydal (see fig. 2) for the rest of their lives. The first surviving journal of their time after returning to live in the Lakes, Dorothy’s first Grasmere journal, was begun on 14 May 1800, in a very small notebook (at 15 x 9.5 cm, it is only slightly larger than an iPhone 8), now known as DCMS 20.

The entries in this journal notebook therefore offer the first glimpses into the siblings’ lives after returning to the Lake District, covering the second half of their first year in Grasmere and tracing Dorothy’s activities as they set up their own household and began, for the first time, to live on their own terms. It was an important period for the Wordsworths, a moment that combined a sense of homecoming with experiences of dislocation and itinerancy. At least in this first year, they were not quite locals, though they were not quite tourists, either. Upon moving to Grasmere, Dorothy and William began the practical labor of creating a home for themselves, as they improved their cottage and garden; made new friendships, particularly with two families resident nearby, the Simpsons and the Lloyds; nourished old intimacies, especially with the Coleridges and the Hutchinsons; reacquainted themselves with Lakeland ways; and walked everywhere, having no other means of transportation and being devoted to pedestrianism as a form of recreation and exploration. The journal also reports on an essential period of their shared literary life, as William composed poetry for the second volume of the second edition of Lyrical Ballads (1800) and as brother and sister prepared the volume for the press.

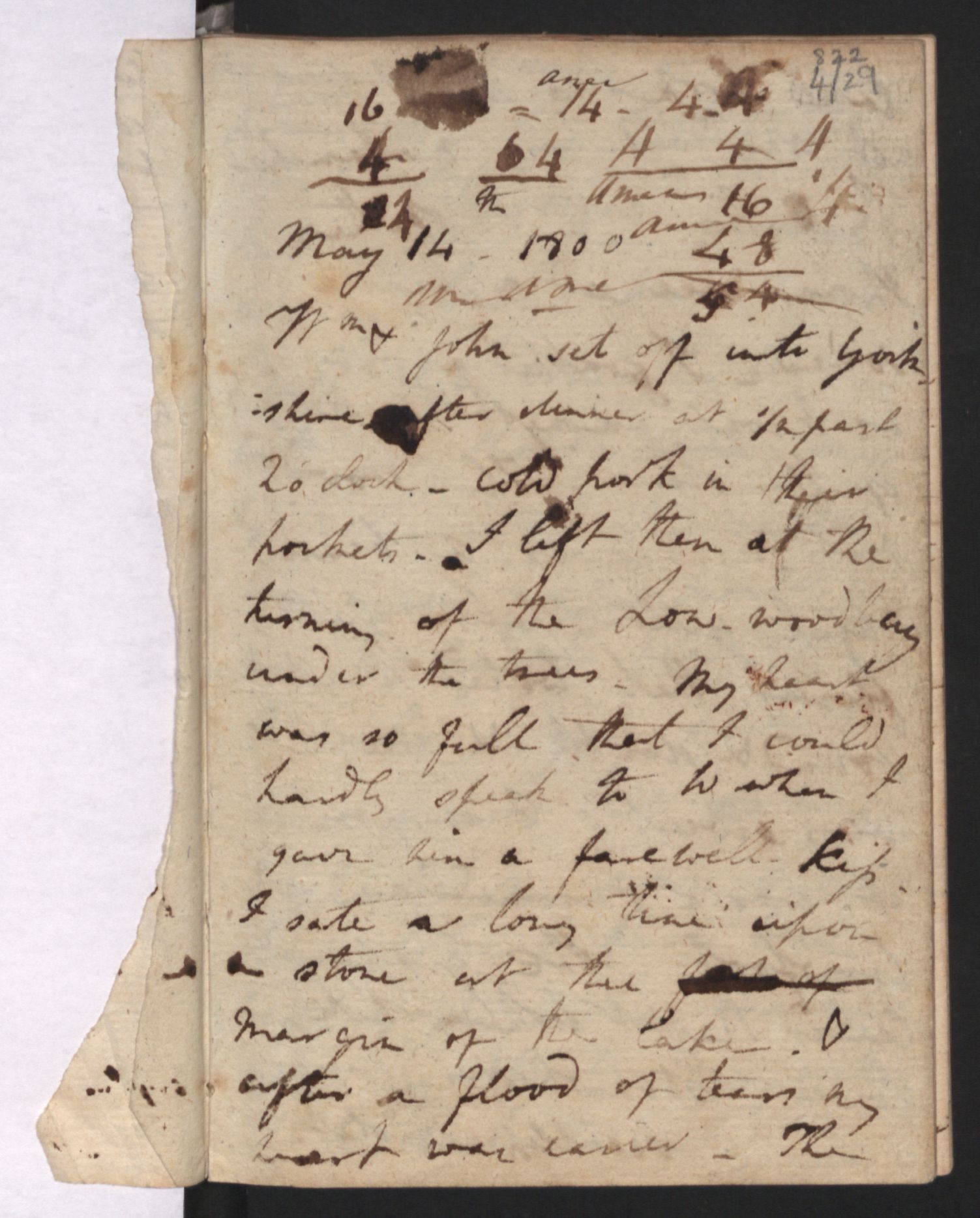

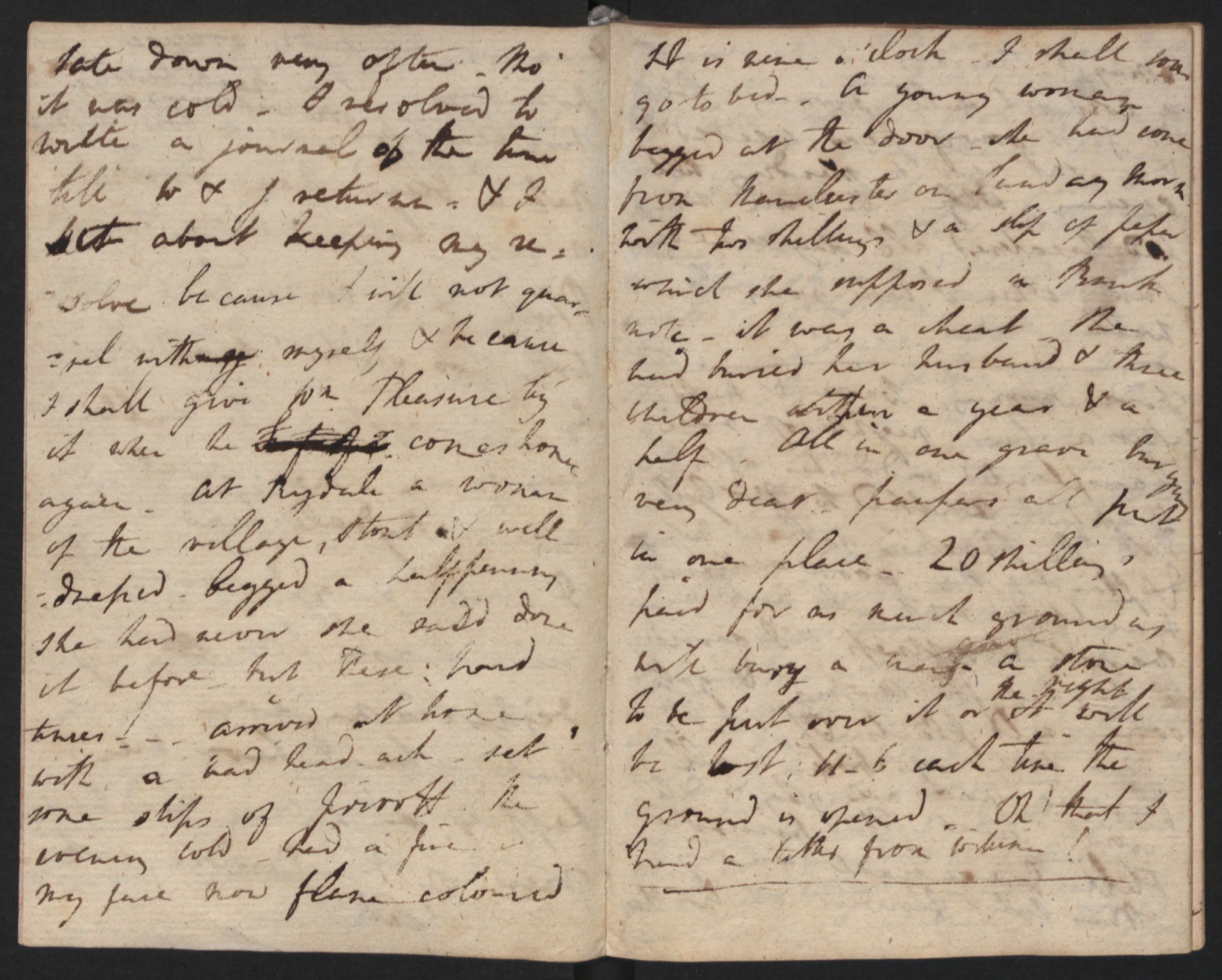

The opening entry in the journal (see fig. 1 for its first page and fig. 2 for pages 4 and 5) is dramatic. In it, Dorothy takes up her pen after the departure of her two brothers, John and William, to visit Mary, Sara, and Tom Hutchinson in their new home in Yorkshire. John, a sailor, had come to live with Dorothy and William in January 1800, after an eight-year separation. William and Dorothy knew the Hutchinsons from Penrith, where Dorothy had gone to live with her maternal grandparents as a 16-year-old. William met the Hutchinsons during school holidays; and he would later marry Mary Hutchinson, in October 1802. All of this context informs our reading of this first entry, which begins with an emotional intensity that is not often repeated. Dorothy finds herself overwhelmed upon saying goodbye to William (“My heart was so full that I could hardly speak to W when I gave him a farewell kiss”); she describes the “flood of tears” that follows and ends the entry with a wish for a letter from her brother (“Oh! that I had a letter from William!”), even though he has only just left. The entry is also remarkable for its length (at 450 words, it is the longest entry that does not involve Dorothy trying to catch up on multiple days) and because, in it, Dorothy describes herself in the present moment of journal writing (“It is nine o’clock, I shall soon go to bed.”). Normally, her journal is retrospective, but in key instances Dorothy writes to the moment.

Figure 1. The first page of Dorothy’s journal entries in DCMS 20. Some of the stubs from the six excised pages at the beginning of the notebook are visible, as are figures scribbled at the top of this page, demonstrating previous uses of the notebook. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

In this entry, Dorothy reflects, directly for the first and only time in the surviving journals, on her purpose for keeping one:

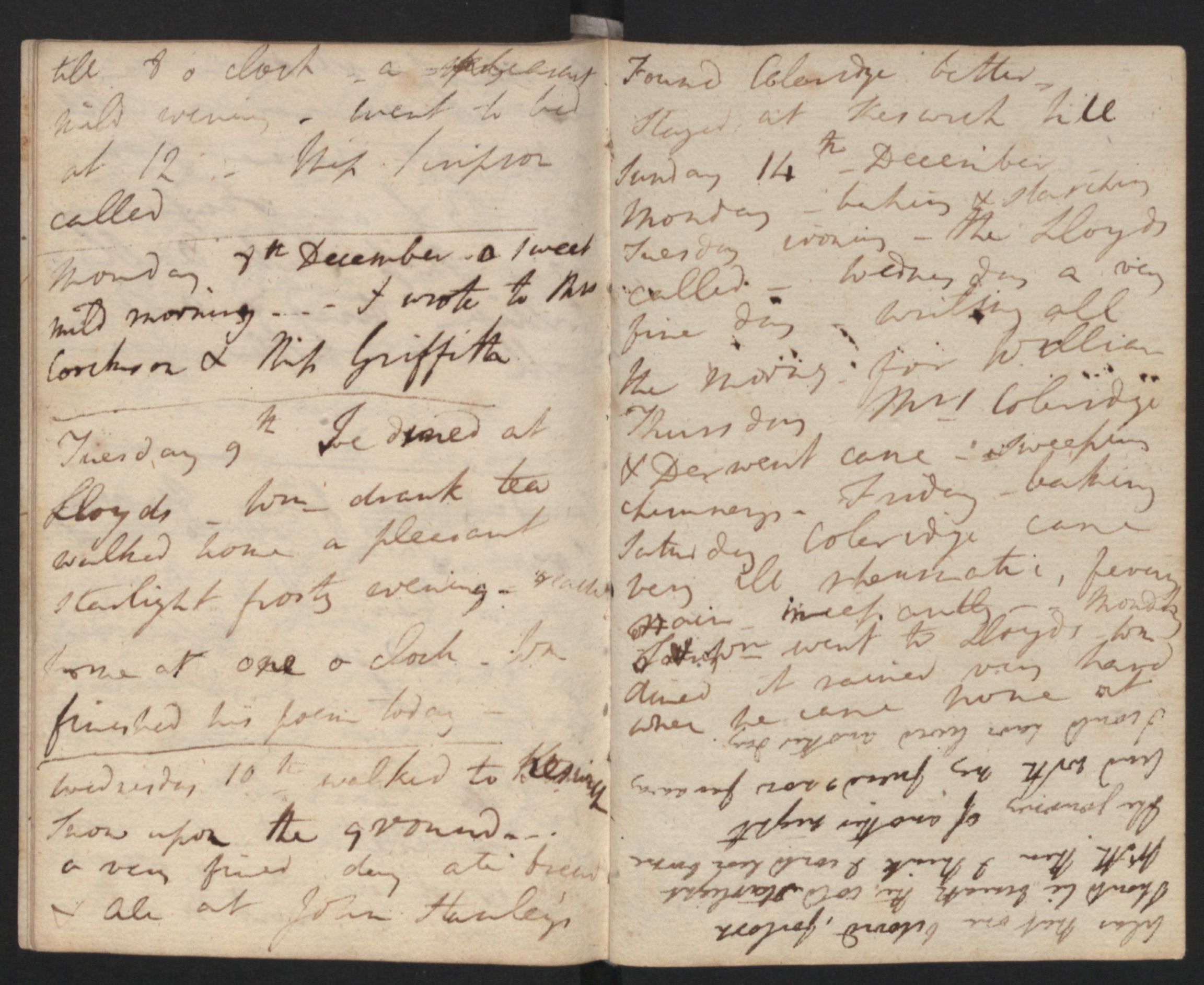

To be sure, she would discover additional uses for the journal over time (just as she had prior uses, as is evidenced in the sums found at the top of fig. 1), but here she frames her resolution to keep it primarily as a means of consoling herself for the grief she feels at the departure of her brothers (“because I will not quarrel with myself”) and as a gift for William upon his return, presumably because it will allow him to share in her daily activities, thoughts, and encounters. The speed with which Dorothy wrote this and most of her other entries is apparent in pages 4 and 5 of her first journal entry (fig. 2). Notice, for instance, her use of abbreviations (W and Wm for William, J for John); in the cancellation of “my,” possibly because it was written too close to the previous word, followed by her rewriting “myself”; and in the deleted and undecipherable word in the middle of page 4. The minuteness of the notebook is also apparent in the very short lines (most have only five to seven words) and in the formation of letters, which though legible are often far from neat.

Figure 2. The fourth and fifth pages of the journal (DCMS 20), showing the notebook open. A ruled line at the end of page 5 indicates how Dorothy usually denotes a break between days. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

Within this first entry, we see how Dorothy’s stated aims coalesce. The act of recording her daily activities offers her solace for her loneliness and allows her to reflect on the productive nature of her days, spent working in the house and garden, reading and writing, visiting with friends, and walking. These activities follow the daily rhythms of life: the chores necessary to run a household, such as washing and mending, as well as those tasks she seems to have taken special pleasure in, such as gathering plants and flowers for her garden. At the end of the first entry, for example, Dorothy reports, “Arrived at home with a bad head-ach – set some slips of privett. The evening cold – had a fire – my face now flame-coloured.” This entry offers a foretaste of the descriptions to come, as she enumerates her daily household chores, all undertaken with a bad headache on a cold May day, after a long and emotionally draining walk. Throughout this notebook, we learn that Dorothy had help with some chores, as she mentions her neighbors from the cottage across the road, John Fisher; his wife, Aggy (Agnes); and his sister Molly (Mary) Fisher. Pamela Woof notes that Molly was paid two shillings a week “to clean, light fires, wash dishes, prepare vegetables, do the weekly small clothes wash, and the 5-weekly ‘great wash.’”

Still, Dorothy had “a good deal” to do (in her own oft-repeated phrase)—ironing, baking, weeding—work that was physically demanding and time-consuming but that also represented acceptable forms of labor for a middle-class woman. The kitchen garden was an important source of food, such as peas and turnips, and it is evident that much effort was needed to grow and harvest these crops, as it was more generally to manage a home at the beginning of the nineteenth century, in one of the wettest parts of England, with minimal help from servants. She also engaged in shoemaking, wallpapering, and mattress making, with one mattress being sent to the Coleridges in Keswick. Dorothy took delight and pride in her pleasure garden, and she transplanted the mosses, plants, and flowers that she gathered on her walks or bought from others. When William returned on 7 June, they stayed up until 4:00 a.m. “so he had an opportunity of seeing [their] improvements” when the sun came up, and she expressed satisfaction two days later when a party in “a coronetted Landau [a luxury carriage bearing an insignia of the nobility] . . . (evidently tourists) turned an eye of interest upon [their] little garden & cottage.”

B. Walking in the Lakes

Dorothy’s encounter with tourists traveling by landau contrasts strongly with her own pedestrianism. The Wordsworths had no horse or carriage in their early Grasmere days and got around on foot. Indeed, perhaps most striking to the modern reader of DCMS 20 is the centrality of walking to Dorothy’s daily life, an activity that brought her into close contact with a landscape she loved, with friends and family (with and to whom she often walked), and with the local farmers and shepherds, beggars, and itinerant laborers who also traversed the public roads and footpaths. Indeed, walking emerges as an organizing feature of her (and her brother’s) daily life. She repeatedly speaks about going out for “[her] walk,” suggesting that it is the walk itself—the physical activity and the opportunity it allows for experiencing her natural surroundings—that serves as the prime motivator for the activity. She rambles through almost all weather, in all seasons, in rain and snow, by moon and starlight, often not returning home until late in the evening. Dorothy was proud of her skill and endurance as a walker. On 18 May, she notes, “I was overtaken by 2 Cumberland people on the other side of Rydale who complimented me upon my walking.” In most entries, Dorothy takes care to describe all of these activities: whether and where she has walked, her household chores, her engagement in sociable activities, and her participation in intellectual and literary work such as reading, copying, writing letters, and, of course, keeping her journal. As the record of an indefatigable pedestrian and a young, single woman interested in the lives and livelihood of others of all ages and social classes, the journal provides its readers with a tour of, informal and unplotted as it is, as well as with commentary on the Lake District’s topography and ecology, and on the life—social, economic, intellectual, creative—of those who live there.

Within the lengthy first entry for 14 May 1800, Dorothy records the walk she takes (after parting with her brothers at the shores of Lake Windermere), including the route she took and her observations along the way. She describes three encounters with individuals as she walks along the public roads: with a blind man driving bulls, with a poor woman from Rydal who begs a half penny, and with a young woman from Manchester who has buried three children and a husband in a pauper’s grave. Walking thus affords Dorothy opportunities for encountering both nature and human nature, and these experiences weave throughout the journal. (Some of them, famously, reappear in William’s poems.) The Rydal woman tells Dorothy that she has never begged before but has been forced to do so because of these “hard times.” The representation of poor men, women, and children, many of whom are homeless and itinerant and forced to beg, whom she meets on her walks and at her door (Dove Cottage was then on the main road, so it was a usual place for those passing through to stop and beg for money or food), attest to the economic dislocations of industrialization and war affecting England at the start of the new century.

Dorothy’s record of and response to the speech, appearance, and actions of these distressed people form an important aspect of her journal. She often reflects on the residents of the vale and how they too are adversely affected by the “hard times.” On 18 May, she quotes her neighbor, John Fisher, who expresses concern “about the alteration in the times,” observing “that in a short time there would be only two ranks of people, the very rich & the very poor, for those who have small estates says he are forced to sell, & all the land goes into one hand.” Several years later, she would address the dire circumstances of small landowners in A Narrative concerning George & Sarah Green of the Parish of Grasmere addressed to a Friend (1808). In her journal entries and elsewhere, we find Dorothy expressing her awareness of and sympathy for the suffering of those around her, as well as her desire to voice their concerns. Indeed, her walking could itself be seen as an act of solidarity with the poor.

Rarely is there an entry in this notebook that does not mention walking. Even when she does not walk, an explanation is usually given for why it has not been possible to do so (the reasons are illness, visitors, or severe weather). Of the 172 days recorded in the journal, Dorothy reports walking on 125, or 73 percent of the total. On 37 of these days, she reports walking two or three times. Some of these walks are left unspecified, such as on 23 November, when we are simply told, “Sarah & I walked after dinner.” However, on many if not most days, it is possible to have a much more precise sense of where she goes. Many of Dorothy’s walks are solitary rambles, but, as noted previously, few days go by without Dorothy visiting or being visited by her friends.

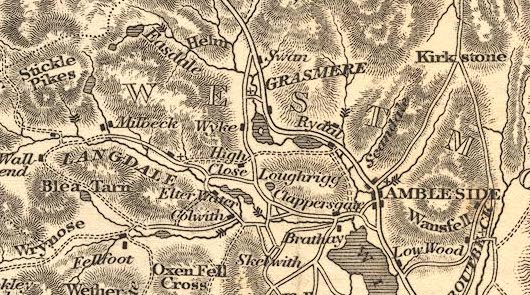

The 1818 map detailed in figure 3, with Grasmere in the near center (and Dove Cottage marked by the rectangle on the road to east of the lake), enables us to better visualize her daily walks, which moved in every direction from her home. One frequent destination was the town of Ambleside, to the south, where mail was delivered and picked up, a distance of about four miles each way. Often, she describes taking the route to Ambleside via Clappersgate. In November 1800, Charles Lloyd, his wife, Mary, his sister Priscilla, and their children moved to Old Brathay, southwest of Ambleside (denoted as “Brathay” on the map), and Dorothy visited them frequently. Clappersgate and Brathay are at the head of Lake Windermere, and it was just south of there, at Low Wood on the eastern shore, that Dorothy parted from William and John as reported in her first journal entry.

Figure 3. Detail from New Map of the District of the Lakes, in Westmorland, Cumberland, and Lancashire, scale about 4 miles to 1 inch, by Jonathan Otley, engraved by J. and G. Menzies, Edinburgh. The map dates from 1817 to 1818. This copy appears in Otley’s A Concise Description of the English Lakes, 5th ed. (Keswick, 1834). (Courtesy: SFU Library, Special Collections and Rare Books)

More westerly is Langdale, the neighboring vale, under the mountains known as the Langdale Pikes. Dorothy reports walking to Langdale on three occasions (16 and 23 June and 7 September): on 16 June she mentions visiting Collath (Colwith) and Skelleth (Skelwith), also visible on the map, and on 23 June she describes seeing Elterwater. She “peeps” into Langdale valley, by climbing around Loughrigg, one of the fells to the south of Grasmere, another two times (30 August and 4 December). To the south and east and closer to home are the neighboring village of Rydal and lake of the same name; and there are also the hills behind Dove Cottage, where Dorothy acquires mosses and plants.

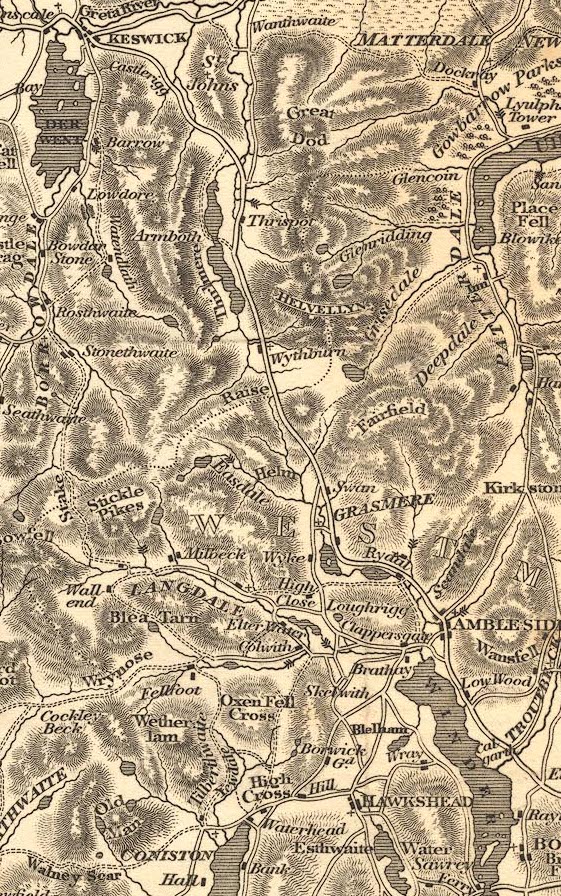

Figure 4, from the same map, takes a wider view to include the area north of Grasmere. In July 1800, Samuel Taylor Coleridge had moved to Keswick, to be nearer to the Wordsworths, his new home at Greta Hall being about 13 miles northeast of Grasmere (along what was known as the Keswick Road, which passed over Dunmail Raise, denoted as “Raise” on the map but spelled as “Rays” by Dorothy). Dorothy walked to Keswick at least three times in the six-month period described in this notebook, in August, November, and finally in December, when her journal entry mentions “snow upon the ground.” On 17 November 1800, she records the time it took for her to walk from Dove Cottage to Keswick for this second trip of the year: “Set off at 5 minutes past 10, & arrived at ½ past 2.” Thus, she covers about three miles per hour, walking uphill much of the way. Much closer to Grasmere but along the same road is the village of Wythburn, a common turning-around point for Dorothy when she accompanies William on the first part of his journeys to Keswick. Dorothy also frequently walks to Wythburn, the home of Miss Elizabeth Jane Simpson and her father, the Reverend Joseph Simpson, vicar of the village’s small church.

Elizabeth was near in age to Dorothy (Dorothy was 29, Elizabeth about 33, in 1800), and the distance between their homes was about 1.5 miles. To the northwest, even closer to home, is Easedale valley, often referred to by the Wordsworths as the “Black Quarter”—a favorite place for their walks; one can also see “Helm [Crag]” on the map, the iconic local fell that looks over Grasmere and Easedale, mentioned frequently in the journal along with other surrounding hills.

Figure 4. Second detail from Otley’s New Map of the District of the Lakes, in Westmorland, Cumberland, and Lancashire.

To some extent, Dorothy’s walking habits depend on who is at Dove Cottage with her. After William’s return from his visit to Penrith, her routine changes slightly; she describes less wandering and more fishing on the lake. When she has company, such as during the extended, 3½-week visit with the Coleridges in July or Coleridge’s visit alone in December, she stops writing in her journal, so we learn less about her walking during those periods (see figure 6). When Coleridge comes, Dorothy appears to be excluded from some longer and more arduous walks undertaken by the men—for instance, Coleridge, brother John, and William climb Helvellyn (England’s third-highest mountain), Seat Sandal, and the path to Stickle Tarn (Langdale) without her. All three destinations may be seen in figure 4 (Seat Sandal is just below Grisedale Tarn, and Stickle Tarn is due east of Stickle Pikes). It is not clear why Dorothy did not accompany the men on these 1800 walks. She would not be left out for long. By late 1801, she had attempted Fairfield and reached the summit of Helvellyn. We know from A Narrative concerning George & Sarah Green that by 1808 she had been to Stickle Tarn. In short, Dorothy would make these ascents (and many others) in the years to come.

Examining and closely reading a single notebook allows us to understand the centrality of walking to Dorothy Wordsworth. Walking was important for her physical and mental health. Certainly, it invested her with a strong sense of independence and personal worth. Many of Dorothy’s later travel narratives also describe her mode of travel as chiefly pedestrian, reflecting the profound importance that walking had for her writing. Furthermore, Dorothy’s inability to walk later in life, when beset by illness, became the subject of one her most celebrated poems, “Thoughts on my sickbed” (see Section 7 of this edition).

C. Writing for the Journals

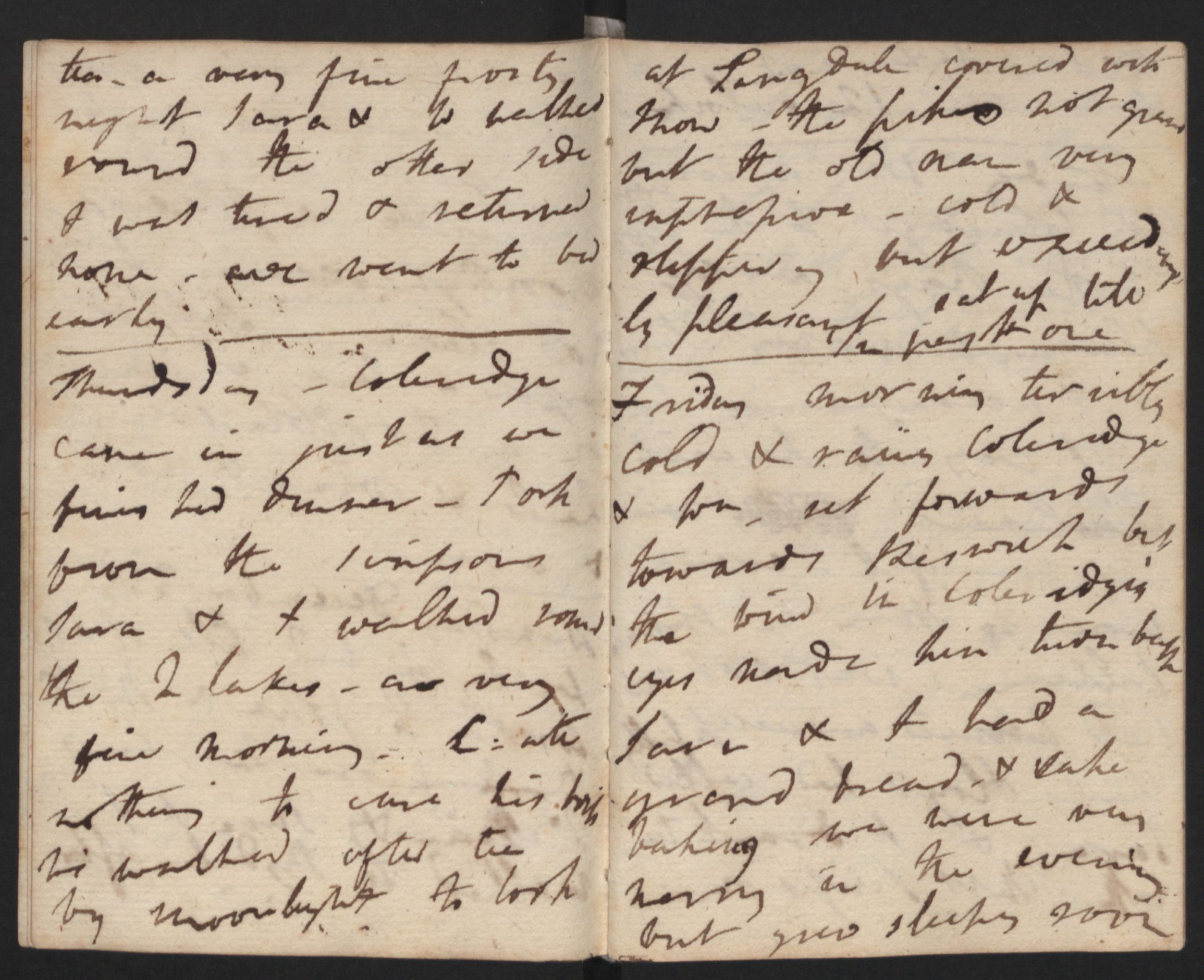

Like most diarists, Dorothy sometimes gets behind, and she writes at highly variable levels of detail. Sometimes she composes retrospectively, and at other times she writes to the moment. In the first entry, as we have seen, she writes in the present, and also on 3 September: “– writing my journal now at 8 o clock.” On 19 October, we seem to catch her writing in installments within a single entry: “We are not to dine till 4 o clock ––– Dined at ½ past 5.” Additionally, there are many indications, both direct and indirect, that Dorothy did not consistently write her entries on the day she describes. In an undated entry after 13 September, she notes, “Here I have long neglected my Journal” and inserts a compensatory entry covering the period from 19 to 30 September. An earlier example appears between 25 June and 26 July. Beneath the entry for 25 June, Dorothy reports that the Coleridges arrived on Sunday, 29 June and stayed for over three weeks, departing on Thursday, 24 July (Dorothy mistakes this date as 23 July). In other words, we have a gap of five days. Moreover, in this catch-up entry, Dorothy provides an extremely truncated account of the Coleridges’ visit. All we learn about this 26-day period (Sunday, June 29 to Thursday, July 24) is that on the Friday before her friends’ departure, the group took tea on the island (in Grasmere); that on the Sunday before they had tea in Bainriggs with the Simpsons, Dorothy accompanied Sara Coleridge to Wythburn; and that the weather was hot. We see a similar brevity at play when Coleridge visits in December (there is a gap between 4 and 15 December; see fig. 6) and when Dorothy travels to Keswick, between 9–16 August and 10–14 December. Sometimes, we conclude, she was just too busy to write.

The Grasmere Journals (the edited and published version of the four Grasmere journal notebooks) have long been read for the way they illuminate the literary labors pursued by, and often shared between, brother and sister. Within the pages of DCMS 20, Dorothy regularly mentions the time she spends reading (sometimes out of doors), writing letters, writing new verse from dictation or copying poetry (such as on 17 December, when she is “Writing all the morning for William”), and of course composing the journal entries themselves. At times, we see such activities overlapping, as when Dorothy copies unpublished stanzas drafted for “Complaint of the Forsaken Indian Woman,” a poem first published in Lyrical Ballads (1798), at the end of the notebook. The journal documents a shared life and shared work.

A careful reading of DCMS 20 also enables us to piece together how Dorothy’s journal entries might have been shared with her brother and how William often took inspiration and even phrases from Dorothy’s journals for use in his poems. On 10 June 1800, just a few days after William’s return home on the 7th, Dorothy includes a long narrative recollecting her encounter with a tall beggar woman and her family from more than two weeks prior. In this case, Dorothy reaches back to record a past event, possibly because after William returned home and Dorothy had told him about it, he asked her to describe it in her journal, their common memory device. In a journal entry from 13 March 1802, we find a precise description of how William returned to this 1800 entry nearly two years later: ‘William finished Alice Fell, & then he wrote the poem of the Beggar woman, taken from a Woman whom I had seen in May–(now nearly 2 years ago) when John & he were at Gallow Hill – – I sate with him at Intervals all the morning, took down his stanzas, &c – . . . . After tea I read to William that account of the little Boys belonging to the tall woman & an unlucky thing it was for he could not escape from those very words, & so he could not write the poem, he left it unfinished & went tired to Bed.'

Also within DCMS 20 we find Dorothy’s lengthy description of a leech gatherer (in an entry for 3 October 1800), which was later used to shape “Resolution and Independence,” drafted between 4 May and 4 July 1802. Perhaps one of the reasons for the careful preservation of this (and other notebooks) is that these uses of the journal entries could be delayed by many years. In some cases, however, the uptake was more immediate: on 11 October 1800, Dorothy describes walking to an abandoned sheepfold in Greenhead Ghyll (the mountain stream that runs to the northeast of the Swan in fig. 3), capturing thoughts and images central to William’s poem “Michael,” which is already being drafted at the time.

Dorothy’s entry of 13 March 1802, discussing William’s vexed attempt to write a poem about the tall beggar woman, suggests that William could feel stimulated but also trapped by Dorothy’s words. It is not known whether the “very words” she uses confine him because he feels obligated not to use them or because—as seems more likely—they dominate his mind, seem impossible to surpass, or do not fit the meter or mode of poetic composition he is attempting. Dorothy seems sympathetic to the writer’s block she has induced (“unlucky thing it was”), though perhaps she takes some pleasure in knowing her words have an impact.

The journal’s descriptions of collaboration, whether smooth or frustrated, raise ethical questions about William’s use of Dorothy’s writing. Such questions have long been a source of interest and concern to feminist scholars who, since the 1980s, have raised claims that William appropriated Dorothy’s work and stifled her creativity, preventing her from becoming “more than half a poet.”

As Patricia Comitini has noted, most “scholarship has focused primarily on [Dorothy’s] failure to realize herself, develop her talent, or establish her own home,” and William’s uncredited use of her writing is often blamed for this.

Ultimately, however, Dorothy’s fate was tied to that of her brother, and his ability to produce marketable poems was indispensable to the family economy. Lucy Newlyn has written eloquently about the siblings’ relationship, understanding that their literary, affective, and economic lives were inevitably intertwined.

It should also be remembered that Dorothy’s economic dependency, as a single woman without property, meant that, practically speaking, she was unable to assert intellectual property in her “very words.”

D. Publication and Reception History of the Journals

It is unknown the extent to which Dorothy’s journal notebooks may have been read by others besides William during the period in which they were being written and subsequently during the remaining 55 years that she lived. We do know that William’s nephew, Christopher Wordsworth, learned of their existence and, in his 1851 Memoirs of William Wordsworth, included over 50 pages from the four Grasmere journal notebooks and Dorothy’s unpublished Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland. According to Mary Ellen Bellanca, the “avowed purpose for excerpting her texts [was] to furnish contexts for the poems,”

and Christopher directly stated that the “materials” like Dorothy’s journals and letters were to be considered “subordinate and ministerial to the Poems, and illustrative of them.”

Nevertheless, as Bellanca explains, many of Christopher’s selections “bear little relation to the poetry or even significant incidents” but were included for their intrinsic merit, and in particular as a means of presenting Dorothy “in effect, as a nature writer.”

Here we find a blueprint for the reception of Dorothy’s writing that to a large extent continues today, in which the Grasmere Journals are understood to be central to her reputation, their value conceived as depending on their descriptions of natural scenery and the context they provide for her brother’s life and poems.

Dorothy’s Grasmere-period journals were first presented to the public in a more complete form than the 1851 Memoirs allowed in William Knight’s Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth of 1897. In his introduction, he notes, albeit with some concern, that “many sentences in the Journal present a curious resemblance to words and phrases which occur in the poems.”

His edition offers special praise for these journals (“To many readers this will be by far the most interesting section of all Dorothy Wordsworth’s writings”) and describes their importance in terms nearly identical to those articulated by Christopher Wordsworth: ‘[The journal] not only contains exquisite descriptions of Grasmere and its district—a most felicitous record of the changes of the seasons and the progress of the year, details as flower and tree, bird and beast, mountain and lake—but it casts a flood of light on the circumstances under which her brother’s poems were composed.

’ Knight enhances this “flood of light” by including footnotes referencing passages in the journal that are echoed in William’s poems, a practice that was continued by her next editor, Ernest de Sélincourt, in 1941.

Fortunately, De Selincourt restored many of the passages Knight saw fit to censor in his edition: chiefly, Knight cut Dorothy’s descriptions of laborious housework, bodily functions, and physical illnesses, as well as her commentary about some members of the community (such as drunken priests and battered wives), which he presumably thought were indelicate to bring before his Victorian readers.

The Grasmere Journals were first initiated into the canon of Romantic literature for the reasons identified by Christopher Wordsworth and William Knight. Brief selections from the journals were the first writing by a woman of the Romantic period to be included in the Norton Anthology of English Literature (in the third edition of 1974), chiefly because they could be used to illuminate William’s poetry.

Notwithstanding significant shifts in how Dorothy’s writing is understood today, nearly 50 years after her first appearance in the Norton, student anthologies continue to emphasize entries that speak to her brother’s poetry, illuminate their shared domestic and emotional life, or (in keeping with the vision of Romanticism as inspired nature writing) foreground Dorothy’s perspicacious observations on her surroundings. For example, the 2000 (7th) edition of the Norton Anthology of English Literature includes only four entries from this first notebook, all of which directly relate to William and his poetry:

- 14 May 1800 (the first entry);

- 3 October 1800 (on the leech gatherer);

- 11 October 1800 (on the sheepfold); and

- 12 October 1800 (which includes descriptions of William composing and Dorothy copying poems and a description of autumnal foliage).

The second edition of the Broadview Anthology of Literature (2006) includes the same first three entries (14 May, 3 and 11 October 1800), and many similar examples might be cited. These anthologizing practices arguably distort the content of the journals, selected because they illuminate William’s creative processes and surroundings. One of our chief aims in representing this first notebook in its entirety (as opposed to making selections from all four Grasmere journal notebooks) has been to focus attention on the richness and diversity of Dorothy’s writing about her life in Grasmere and also to provoke us to understand that while her brother and his poetry were important elements of her life, they were not centrally or exclusively what the journal was about.

Additionally, many print sources ignore the materiality of the originals and the obvious facts that the entries were handwritten, seemingly quickly, in very small notebooks, often many days after the scenes and events described. Selections such as we find in modern anthologies often provide a false impression of the journal entries as carefully wrought vignettes, products of a reflective, sedate life. This edition counters these impressions by reproducing, as precisely as possibly, Dorothy’s words in a diplomatic transcription. In addition, facsimiles of several notebook pages have been provided to help the reader to understand the appearance and dimensions of the notebook, the entry system Dorothy used, and the handwriting within it. By these means, we can trace how Dorothy missed or misdated days, made strikethroughs and emendations, and generally wrote in haste, in moments snatched at the end of what appear to have been very full and tiring days. We can observe Dorothy including references to individuals and places without providing explanation or context, as it was unnecessary for her to do so given her imagined (and actual) audience of her brother. The next section provides more detail about the material nature of the notebook and our edition of it.

II. Textual and Editorial Issues

Unlike the writings by Dorothy included in most other sections of this edition, no one, including Dorothy, recopied the first Grasmere journal notebook. It exists in a single manuscript, DCMS 20. As we have seen, Dorothy was prompted to begin the journal because of the departure of her brothers on a trip to Yorkshire.

Three other notebooks (DCMS 25, 10 October 1801 to 14 February 1802; DCMS 19, 14 February to 2 May 1802; and DCMS 31, 4 May 1802 to 16 January 1803) make up the remainder of what are now called the Grasmere Journals, though there is a gap between the first notebook and the second. The last entry in DCMS 20 is dated 22 December 1800, and it ends midsentence. In another notebook, now missing, Dorothy likely continued this sentence; and she continued that journal in the next surviving Grasmere notebook (DCMS 25), which begins at 10 October 1801, more than nine months after DCMS 20 abruptly ends. Dorothy would continue to write journals, across multiple notebooks, for most of her life. We include selections from the Rydal notebooks in this edition.

As mentioned previously, DCMS 20 is small, measuring just 15 x 9.5 cm, with mottled brown paper covers. It was not unused when Dorothy came to it in May 1800. Remaining stubs of cut-out pages have discernible writing on them, as do the endpapers. As Pamela Woof explains, the stray figures, accounts (see fig. 1), lists, and German words indicate that the notebook had been used during the Wordsworths’ visit to Germany in 1798–1799.

The notebook as we have it now begins in one direction with the first journal entry; however, before that, it had apparently been used the other way round. From the other end, following the five cut-out pages, Dorothy copied down four epitaphs from her visit to Durham in the early summer of 1799.

The epigraphs are followed by five unpublished stanzas of William’s “Complaint of the Forsaken Indian Woman,” a poem first published in Lyrical Ballads (1798). These verses end halfway down a page, with the final journal entries for December 1800 meeting them but being written with the book rotated 180 degrees (see fig. 5). Transcriptions of the epitaphs and William’s poem are included in our edition to demonstrate the heterogeneous nature of the notebook’s contents. They also remind us of the thrift involved in writing within the Wordsworths’ household; as a partially used notebook, with many pages remaining, it was available for reuse. Paper was an expensive commodity during the period, and making the most of a small notebook was another way to practice economy. As a notebook, moreover, DCMS 20 could be easily transported: we know Dorothy had it in Germany, and it is also possible she brought the notebook with her when she went to visit the Coleridges in Keswick, though if she did, she used it sparingly.

Figure 5. The last page of DCMS 20, shown to the left, with the final journal entry, to the right, including lines of William’s Complaint of a Forsaken Indian Woman. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

Dorothy left no room, in the top or bottom or side margins, or between the lines, for additions, once again demonstrating thrift in using all available space (see fig. 2.5) and suggesting no intention to revise the journal entries. She did on occasion cancel a word or two, and in those cases where a deleted word (or two or three) cannot be made out, it is noted (as “[illegible deleted word]”) in the transcription. Many of the changes were made in the first instance of writing, as a word was crossed out and immediately replaced in the same line. Dorothy does appear to have returned to the manuscript after the entries had been made, however, and made some changes, particularly to correct dates, which she had frequently mistaken.

Figure 6. Entries for Wednesday and Thursday, 3 and 4 December, and Friday, 15 December, in DCMS 20. The entries do not register the gap of 11 days during Coleridge’s visit. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

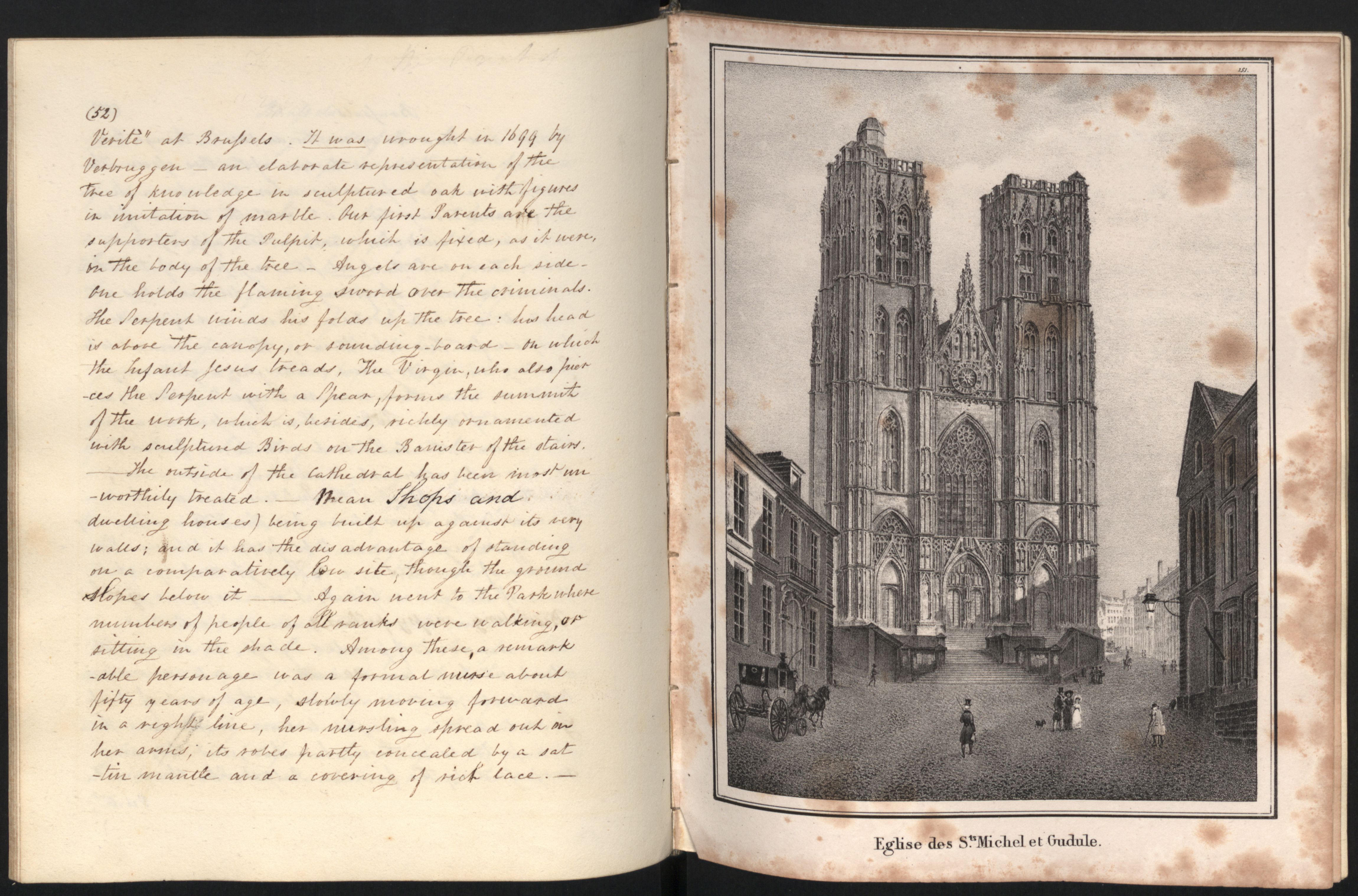

The handwriting throughout the notebook is legible but variable in size and far from tidy. It is quite different from the careful, even hand we see on display in her fair copies (such as the hand that appears in her Journal of a Tour of the Continent, DCMS 90—fig. 7) but more like the writing of her informal letters. Her punctuation is erratic. Indeed, often there is no punctuation at all, and when there is, her dashes, periods, and commas are often indistinguishable. We have not edited her writing to include additional punctuation, and we have tried to reproduce her marks as they appear, though doing so often presents a challenge (as in marks appearing in unexpected or indeterminate places or the many canceled words that are impossible to decipher). In addition to her handwriting and mistakes in dating, the lack of punctuation reinforces the conclusion that Dorothy usually wrote quickly. In keeping with the journal form, she dates her entries (though again, often erroneously and irregularly) and uses ruled lines to signify breaks between them. Discernible changes in the ink and handwriting between the entries are rare.

Figure 7. DCMS 90, 52, Journal of a Tour on the Continent. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

Readers interested in the remaining three journal notebooks are urged to consult Pamela Woof’s Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Grasmere and Alfoxden Journals (2002).