Dorothy’s Forgotten Diaries

Despite Dorothy Wordsworth’s having long ago joined the pantheon of English diarists, her most sustained effort in the genre, the fifteen compact notebooks from 1824–35 generally identified as the Rydal Journals (RJ), remains largely unpublished and virtually unknown outside specialized academic circles. While several of the more striking passages from these journals have been referenced in the occasional biography or scholarly article, only one short segment—a three-week stretch chronicling her 1828 trip to the Isle of Man—has appeared in its entirety.

Accordingly, this concluding section of Dorothy Wordsworth’s Lake District marks an important first step toward rectifying this problem, as it features complete transcriptions of the first and last volumes (Notebooks 1 and 15) of what proved to be the last great endeavor of Dorothy’s writing career.

Paradoxically, one of Dorothy’s foremost champions, the early twentieth-century Oxford don Ernest De Sélincourt, is perhaps most culpable for consigning the RJ to obscurity. For in both his landmark study of her life (1933) and his two-volume edition of her journals (1941), De Sélincourt categorically dismissed the RJ as “eleven shabby little notebooks,” calling them “wholly capricious” in design and displaying “little of the character of the Alfoxden or Grasmere Journals.”

To justify how, in a collection putatively featuring all of Dorothy’s journals, he included just a tiny fraction of the RJ, he somewhat feebly asserted that the Isle of Man tour is “the only portion written in consecutive style, as a journal rather than a mere diary.”

While assertions like these have undoubtedly suppressed interest in the RJ, numerous researchers and enthusiasts have nonetheless made pilgrimages to Grasmere to study the original notebooks at the Wordsworth Trust. In the 1970s Carl Ketcham transcribed roughly 20% of the RJ and then summarized his findings in a lengthy article published in The Wordsworth Circle in 1978.

Where he, like many Wordsworthians of his generation, turned to Dorothy’s journals primarily for insights into the life and works of her famous brother, subsequent scholars have firmly reinstalled Dorothy at the center of the RJ narrative. In an important 2015 article on “Dorothy Wordsworth and Old Age,” for instance, Pamela Woof offered what was at the time the most thorough engagement with these later notebooks since Ketcham’s essay. And, in 2021, a pair of writers based three radically different books on the RJ: a historical novel on Dorothy’s final years (Kathleen Winter’s Undersong), a poetry collection on themes of ageing and illness (Polly Atkin’s Much with Body), and an alternative biography incorporating perspectives from disability studies (Atkin’s Recovering Dorothy).

That, in order to write about the journals, each of these researchers had to independently copy out those portions that pertained to their interests underscores the need for a reliable and readily accessible transcription of all fifteen volumes of the RJ. While such an undertaking is beyond the scope of this edition, we are excited to make available for the first time fully annotated and contextualized transcriptions of Notebooks 1 and 15. These bookend volumes of the RJ cover dramatically different life stages, the one a period of robust health and the other of increasing infirmity. Yet they share both a setting (Rydal Mount and its environs) and an abiding emphasis on Dorothy’s love for the people and landscapes of her native region.

Notebook 1 spans December 1824 through December 1825, capturing the daily routines of an unusually vibrant 53-year-old who clearly relished a new phase with fewer domestic responsibilities, relative financial security, and a large circle of friends within walking distance of home. Notebook 15, by contrast, chronicles a comparatively dispiriting six-month period of late 1834 and early 1835, when, having survived several recent brushes with death, Dorothy found her experience narrowed to her memories and what she could see or hear from her upstairs bedroom at Rydal Mount.

The Text of the Rydal Journals

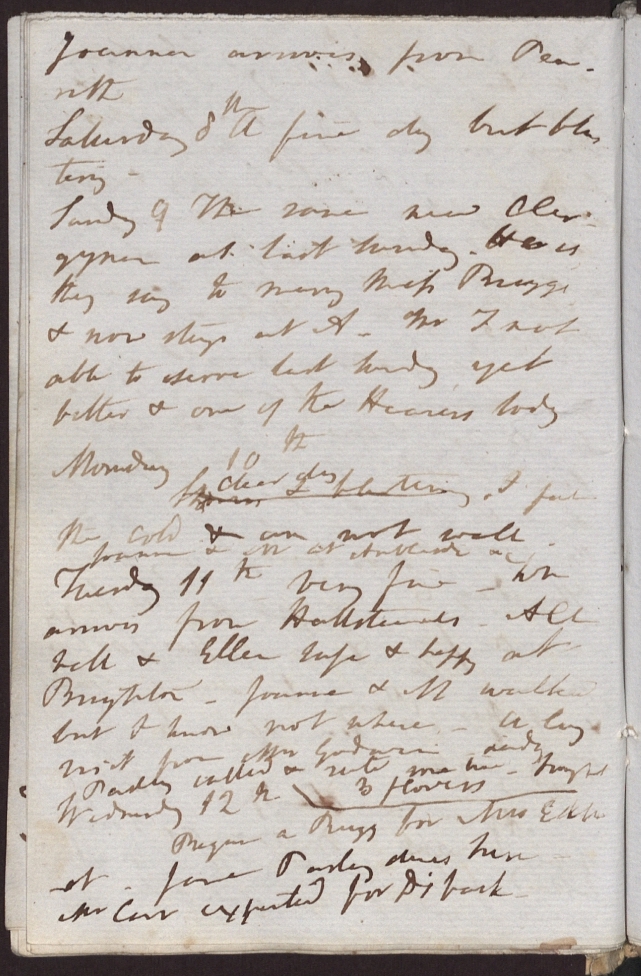

The typical RJ entry consists of three or four succinct, allusive, and fragmentary descriptions written in the slapdash hand that Dorothy often called “my scrawl.” While full of compelling observations and vibrant descriptions, the RJ are considerably more prone than the GJ to lapsing into bare-bones accounts of the weather, the day’s events, and the health of Dorothy’s housemates. This “sparser” style of the later journals has prompted Lucy Newlyn to conjecture that their “main purpose was to serve as a rudimentary mnemonic device” or perhaps as a “mood-diary.”

For his part, Ketcham discerns a subtle artistry in Dorothy’s “customary brevity,” remarking that the finest entries in the RJ combine “a vivid, staccato impressionism with the awareness of underlying unity.“

In keeping with her former practice, Dorothy typically composed several entries in one sitting rather than writing in her journal every night, and she continued to have no compunctions about using the same notebook as a journal, commonplace book, and expense ledger.

Yet, whereas the GJ was explicitly written for her brother William and a few close friends and relations, the RJ seem to have been intended solely for Dorothy’s own benefit. Alternations and emendations in these journals consistently appear in the same shade of ink and quality of pen as the original entry, suggesting that Dorothy almost invariably corrected her prose as she wrote rather than in some later round of dedicated revision. In consequence, this section varies from other parts of this edition in only noting those textual variants or irregularities that might offer fresh perspectives into Dorothy’s writing process. Above all, our priority has been to provide clean and accurate transcriptions that faithfully preserve Dorothy’s final wording, spelling, and punctuation.

Figure 1. Page from Notebook 15 (covering 8–12 November 1834) showing the quality of handwriting and types of revisions typically found in the RJ.

After countless passes through the original manuscripts, we have become sufficiently familiar with Dorothy’s handwriting, diction, and orthography to now be able to offer confident transcriptions of over 95% of the text. Where our transcription remains tentative, we enclose the elusive word or phrase in editorial brackets and add a question mark (e.g., [night?]). If unable or unwilling to hazard a tentative transcription, we use an empty set of editorial brackets ([ ]) to mark each illegible word. Dorothy’s idiosyncratic punctuation poses a different set of challenges, as she routinely omits apostrophes in possessives (e.g., “Marys book”), treats line breaks as a substitute for end punctuation, and does little to distinguish her short dashes from her commas and periods. While careful to retain her punctuation, we have provided clarifying punctuation marks, always placing them inside editorial brackets (e.g., Mary[’]s book), as needed.

Since even a clean transcription of the RJ can be opaque without some knowledge of the people, places, and events being described, we preface both notebooks with a brief introduction and an extensive biographical index covering individuals who appear most frequently therein. And within the text of the journals, we supply scores of hypertext annotations in hopes of helping readers have an even more engaging experience with Dorothy’s remarkable accounts of life in Rydal in the 1820s and 1830s.