I. Contexts

On 19 March 1808, husband and wife, George and Sarah Green, died attempting to cross Langdale Fell on their way home during a storm. They lived at the far end of Easedale, about two miles northwest of the Wordsworths, who were living in Dove Cottage, Town End, Grasmere, at the time and had employed one of the Greens’ daughters, Sally, as a maid. The Greens’ deaths orphaned eight children under the age of 16 and six under age 11, as well as six grown children by previous marriages.

George Green was 65, and Sarah, considerably younger at 43, had recently given birth to a baby girl.

The loss of the parents threw “the whole vale,” in Dorothy Wordsworth’s words, into “the greatest consternation.”

A. “Laying Schemes” to Help the Orphans

Nine days after the tragedy, Dorothy reported to her friend Catherine Clarkson that the Wordsworths had immediately been “employed in laying schemes to prevent the children from falling into the hands of persons who may use them unkindly.”

The specific fear was that the young Greens would suffer the usual fate of orphans, being boarded out by the parish to foster families paid a mere two shillings per week per child. Accordingly, the Wordsworths began to solicit donations, and a brief account of the events was written by William and circulated to those who might be willing to contribute (see William Wordsworth on the Greens).

It seems that the Wordsworths were tireless in their efforts, as William, in a letter to Francis Wrangham dated 17 April 1808, apologizes for the “dim transcript made by a multiplying writer, we having had occasion to make so many copies.”

A letter from William to Coleridge written precisely one month after the tragedy, on 19 April 1808, included a copy of a short poem he had written entitled “Elegiac Stanzas composed in the Churchyard of Grasmere, Westmorland, a few days after the Internment there of a Man and his Wife, Inhabitants of the Vale, who were lost upon the neighbouring Mountains, on the night of the nineteenth of March last” (see William Wordsworth on the Greens).

William urged Coleridge, who was then in London delivering a series of lectures, to “turn these verses to any profit for the poor Orphans in any way, either by reciting, circulating in manuscript or publishing them.” William also explained, “As soon as she has leisure Dorothy means to draw up a minute detail of all that she knows concerning the lives and characters of the Husband and Wife, and everything relating to their melancholy end, and its effect upon the Inhabitants of this Vale; a story that will be rich both in pleasure and profit.” Dorothy, in fact, had begun drafting her own record at roughly this time, as evidenced by her noting near the beginning of her account, “It was a month yesterday since the sad event happened.”

The end of the “Narrative” is signed and dated 4 May 1808, suggesting that Dorothy completed it over a period of two weeks.

The success of the Wordsworths’ efforts in securing funds is immediately apparent upon perusal of the subscription book they kept to record donations pledged and received. By the middle of May 1808—just two months after the tragedy—more than £300 had been raised, and by September 1808 almost 300 donors had pledged nearly £500. Individual pledges varied, as we would expect, largely according to the means of the donor, ranging from the 10 guineas given by both the Bishop of Llandaff and Lord Muncaster to offerings of mere sixpences by local laboring people and servants, many of whom could probably ill afford even these small sums.

Somewhat surprisingly, so far as the records show, the Wordsworths made no direct monetary contribution themselves. This was probably owing to their own straitened financial circumstances in 1808 or rationalized in terms of their deciding to retain Sally Green after the tragedy instead of letting her go, which had been their plan. The Wordsworths’ belief that the charity bestowed upon the Greens had, in some way, to be circumscribed is readily apparent in their decision to cap at £500 the funds raised for the orphans in order not to raise the children above (or at least significantly above) their prior station.

This led to significant friction with Coleridge, who questioned both the belief that the subscription should be capped and the Wordsworths’ decision to sell the entire contents of the Greens’ cottage. Other hints of worry over possible unintended consequences of assisting the family occur in the “Narrative.” Dorothy, for instance, notes the initial concerns of some genteel women who housed the children before their placement in new homes. Fears had been expressed that “wayward desires” in the children might be raised “by the luxuries among which they had lived for the last three weeks.” While Dorothy expresses her relief (and that of the other women) “that [their] fears that this might happen were ill-grounded,” the articulation of this worry is in itself revealing.

The Wordsworths were far from unassisted in supervising the collection of funds and the placement and upbringing of the Green children. The rector of Grasmere, the Reverend Thomas Jackson, agreed to act as trustee, and George Mackereth, the parish clerk, was appointed official collector. Six local women—Mrs. Watson (the wife of the Bishop of Llandaff), Mrs. Lloyd (wife of author Charles Lloyd), Mrs. King and Mrs. North (both recent settlers in the neighborhood), a Miss Knot, and William’s wife, Mary—were appointed to superintend the collection of subscriptions, administer the funds collected, and oversee the care of the children in their new homes. For the next 21 years, until the youngest Green children were able to support themselves, the trustees distributed the funds to the families who had taken in the younger orphaned children, deservedly earning Ernest de Sélincourt’s praise as “a model of a simple act of charity wisely conceived and scrupulously administered.”

Surviving receipts in the Wordsworth Trust archives from the women-led effort (see fig. 1) to finance the children’s schooling, medical care, and clothing allow historians to piece together a vivid portrait of the care of these children. Dorothy’s “Narrative” in particular demonstrates how the work of charity and caregiving was largely a female endeavor.

For the most part, these women worked harmoniously in the service of the children. Susan Levin has described Dorothy’s story as “an affirmation of a certain mode of social assistance” and a “positive description of a community in which experience and relation of that experience almost conflate.”

For Susan Wolfson, Dorothy’s general “social sensibility” throughout her prose and poetic works, including the “Narrative,” differentiates her writing from William’s “more solitary poetics.”

Nevertheless, in the “Narrative,” Dorothy cannot help criticizing one Mrs North, who “cannot do a charitable action without the pleasure of being busy.” As this strikethrough suggests, Dorothy censors herself, deleting her bitter complaints and canceling her antagonist’s name. Elsewhere in the manuscript she writes, “I will not blemish a narrative of events so moving, which have brought forward so many kind and good feelings, by entering into the cabals and heart-burnings of Mrs North.” Throughout DCMS 64, Mrs. North’s name is completely erased, revealing that Dorothy was sufficiently concerned about the circulation of the “Narrative” to accentuate discretion as well as an impression of local solidarity.

B. Dorothy as Social Historian

The “Narrative” is a remarkable work of local history, one that utilizes Dorothy’s talents as a precise and compassionate recorder of speech and events. Both a keen observer of and a participant in this crisis, she brings the perspectives of both an outsider and an insider: an outsider in that the Greens, as poor farmers, belonged to a different class and moved in different social circles; and an insider in that, as an inhabitant of Grasmere Vale, she possessed a deep understanding of the Greens’ way of life and had a firsthand perspective on the aftermath of the parents’ untimely deaths.

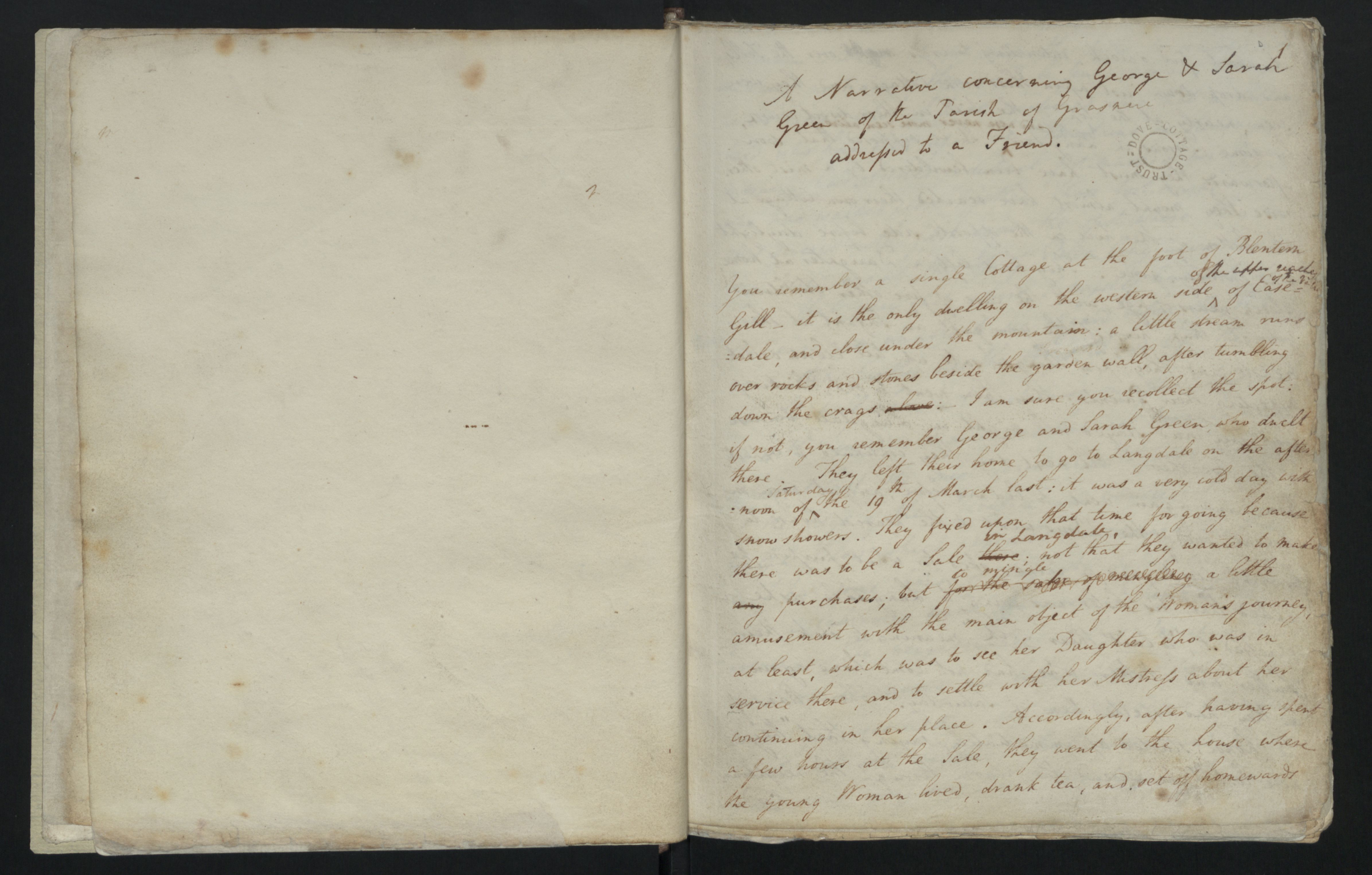

Figure 2. First page of Dorothy’s “A Narrative concerning George & Sarah Green of the Parish of Grasmere addressed to a Friend” in DCMS 64. (Courtesy: Wordsworth Trust)

Dorothy’s insider status is apparent in her direct addresses to her confidential readers, namely those members of her social circle she expected would read her account in manuscript. The full title of the “Narrative” includes “addressed to a friend,”

and its opening line—“You remember a single Cottage at the foot of Blentern Gill”—is one of many nods to a knowing audience familiar with Grasmere and its environs (see fig. 1). While implicitly directed toward a broader, if still localized, readership, the more specific addressee of the “Narrative” appears to have been Dorothy’s good friend Catherine Clarkson. The Clarksons urged Dorothy to publish the “Narrative,” and a complete manuscript copy of the text remains in the Clarkson papers at the British Library.

Throughout the “Narrative,” Dorothy draws her anticipated readers into the story, inviting them directly to feel compassion for the Greens (“You will wonder how they lived at all and indeed I can scarcely tell you”), to participate in the unfolding of events (“It would not be easy to give you an idea of the suspense and trouble in every face before the bodies were found”), and to identify with the charitable actions of those who came to the aid of the orphans (“You will not wonder, after what I have said, that we have been anxious to preserve these Orphans”). In this way, Dorothy assumes sympathetic readers, though at moments she acknowledges a gap between her own feelings and those of readers like the Clarksons who lived outside the Grasmere community: “I cannot give you the same feelings that I have of them as neighbours and fellow-inhabitants of this Vale; therefore what is in my mind a full and living picture will be to you but a feeble sketch.”

Dorothy’s “Narrative” also assumes a readership familiar with and concerned about the fate of small landowners like the Greens who, despite their tireless labor, could barely subsist on their land. She describes the Greens as being ‘the poorest People in the Vale, though they had a small estate of their own, and a Cow. This morsel of Land, now deeply mortgaged had been in the possession of the Family for generations, and they were loth to part with it: consequently, they had never had any assistance from the Parish.’ Dorothy offers many examples of their extreme poverty—how George Green, age 65, had to do odd jobs for neighbors and dig peat from his own land; how the children were hired out to work for local families; how, after their parents’ deaths, the orphans were found with no money, little food, and apparently on the edge of starvation: ‘They must very soon have parted with their Land if they had lived; for their means were reduced by little and little till scarcely anything but the Land was left. The Cow was grown old; and they had not money to buy another; they had sold their horse; and were in the habit of carrying any trifles that they could spare out of house or stable to barter for potatoes or meal. Luxuries they had none—they never made tea, and when the Neighbours went to look after the Children they found nothing in the house but two boiling potatoes, a very little meal, a little bread, and three or four legs of lean dried mutton.’

In such descriptions, Dorothy revisits an archetype that had figured in her journals and her brother’s poetry— “Michael: A Pastoral Poem” being the best example of the story of a small landowner (or statesman, as they were called) at risk of losing his land. Michael is forced to make a heartbreaking decision between selling his land and sending his son, Luke, to work in the city. Ultimately choosing the latter proves both a terrible and futile decision, terrible because Luke becomes dissipated and never returns home, and futile because after his parents’ deaths “the estate / Was sold, and went into a stranger’s hands”;

thus, both Luke and the land are lost. In a journal entry for 18 May 1800, Dorothy records a conversation with her neighbor, John Fisher, who similarly describes the extinction of the class of small landowners: “He talked much about the alteration in the times, & observed that in a short time there would be only two ranks of people, the very rich & the very poor, for those who have small estates says he are forced to sell, & all the land goes into one hand.”

For Dorothy and her audience, the Greens were similarly situated and equally tragic: they represented the passing away of a “pastoral” life (to use William’s subtitle), one that seemed increasingly under threat. It may be that drawing the plight of these families to public notice was “the work” that Thomas Clarkson had in mind in urging Dorothy to publish the narrative; a request that prompted her well-known reply to Catherine Clarkson, on 9 December 1810, discussed in detail below.

How much did the Wordsworths know about the Greens’ poverty prior to their deaths, and were they willfully blind to it? In a 2003 essay, “The Wordsworths, the Greens, and the Limits of Sympathy,” I explored the social commentary in the “Narrative,” in particular Dorothy’s representation of the Greens’ poverty and the nature and circumstances of the subscription raised for the children. Two of the main claims advanced in the essay relate to Dorothy’s representation and treatment of the poor. Although Dorothy insists on a number of occasions that she and her family were unaware of the Greens’ extreme deprivation— “Alas!,” she writes at one point, “we gained our knowledge [of their extreme poverty] since their death”—the “Narrative” also betrays a sense of personal and collective guilt over having, perhaps willfully, ignored so many warning signs. The Wordsworths possibly felt culpable, having had one of the older girls, Sally Green, in their service at the time of the tragedy. They knew, as Dorothy notes in the text, that “one of the little Girls, our own Sally or another, used to come to fetch [our used tea leaves] two long miles!” Just before the tragedy, the Wordsworths had insisted that the Greens purchase Sally two new shifts, or smocks, to fit her out for service in their house, an expense Dorothy subsequently realized must have caused great hardship.

In attending the shop in Ambleside to see if the cloth for these shifts had been paid for after the deaths of George and Sarah Green, and finding that it had, Dorothy reports that many members of the local community had considered the Greens “rather ‘too Stiff,’ unwilling to receive favours but the ‘keenest Payers’, always in a hurry to pay when they had money.” These remarks suggest the impossible situation that families like the Greens found themselves in: paying their debts subjected them to being called prideful; yet no doubt they would have been subject to worse insults if they had not paid. In an age when accepting charity was considered a sign of weakness, one can see how the Greens were in a hopeless predicament. Dorothy is therefore at pains to demonstrate the Greens’ worthiness, an effort to meet the standard that had been set for the deserving poor (one that is also found in William’s short narrative used to raise funds for the orphans; see William Wordsworth on the Greens). In William’s narrative, compassion for the children is “more deeply felt,” and “a general desire that more than ordinary exertions should be made” prevails because of the parents’ “frugality and industry” and “even cheerful endurance of extreme poverty.” In Dorothy’s account, she seems less willing to describe the Greens’ suffering as evidence of moral strength, perhaps reflecting her own conflicted views about the treatment of the poor generally, and about her family’s treatment of the Greens specifically. Indeed, in the most significant set of deletions in the “Narrative,” she cancels several lines that embody this understanding of the Greens as willingly suffering the burden of poverty: ‘… I must say that the general feelings have been purely kind and benevolent, arising from compassion for the forlorn condition of the Orphans and from a respectful regard for the memory of their Parents who with unexampled chearfulness, patience and self-denial, had supported themselves and their Family in extreme poverty; and have left in them a living testimony of their own virtuous conduct: for the Children’s manners (I again repeat it) are of one innocent, [illegible deleted word] and affectionate in a remarkable degree, so that each of them has already made Friends of [illegible deleted word]. (30)’ These cancellations may suggest her inner conflict over such conceptions of the poor.

As noted previously, Dorothy writes the “Narrative” as a local historian, describing a village and way of life in which she is embedded and about which she can be neither objective nor disinterested. She documents the mourning of an entire community. Not only does she relate her own knowledge of the Greens prior to the tragedy as well as that of others who knew them, but she also describes the affecting scenes of the children’s grief upon learning the fate of their parents and their struggles in settling into strange new homes. Much of the “Narrative” consists of what Dorothy describes as the “fireside talk in our Cottages”; it is in such domestic settings, she writes, that one hears “the inner histories of Families, their lesser and greater cares, their peculiar habits, and ways of life [that] are recorded in the breasts of their Fellow-inhabitants of the Vale.” In recording this “fireside talk,” Dorothy becomes the voice of the community, situating herself within a fellowship that not only rallies behind the orphans but also implicitly questions whether the village could have done more to help the family before the parents’ death. Dorothy’s “Narrative” evokes the shared locality in which they live: Easedale, where the Greens made their home and the Wordsworths frequently rambled; the nearby fells upon which the Greens met their fate; the local homes into which the orphans are taken, temporarily and permanently. Dorothy is also very much present throughout the “Narrative” as a character who experiences and expresses the sympathy on which the story turns. In reflecting on the place where the Greens were lost, she recalls her own experience “at the top of Blea Crag above Easedale Tarn, that very spot where I myself had sate down <three> six years ago, unable to see a yard before me, or to go a step further over the Crags.” Anyone, she suggests, might have shared the Greens’ fate, as a mountain-walker like Dorothy had special cause to know.

Dorothy’s sympathetic connection to the Greens must also have been related to her own status as an orphan: Dorothy and William (and their three brothers Richard, John, and Christopher) were, like the Green children, bereft of their parents at young ages: their mother died in 1778 and their father in 1783. Dorothy and William, again like the Greens, were sent to different relatives after the deaths of their parents, not seeing each other for nine years. By 1808, Dorothy had been reunited with her brother for a decade, yet she must have keenly understood the pain felt by the Green siblings, many of whom were separated though most of them, happily, remained in the same vale. Only the eldest boy, George (age 10), was placed with a relative, a half-brother in Ambleside; the rest of the younger Green children joined new families. Since, as Dorothy notes, “It had been declared with one voice by the people of the Parish, men and women, that the Infant and her [11-year-old] Sister Jane should not be parted,” they were together placed with a childless couple. The two youngest boys, William (age four) and Thomas (age three), both still “in petticoats,” were kept together in the home of a family with grown children. John (age seven) was taken in by John Fleming, a sheep farmer who had been a friend of his father. In contrast to Dorothy’s own experience as an orphan, being sent to a distant home in Halifax, West Yorkshire (and later to others, some welcoming and some less so), the Green children were all kept close to their native vale and placed with families that seemed genuinely devoted to them. As Dorothy concluded, “The general feelings have been purely kind and benevolent, arising from compassion for the forlorn condition of the Orphans and from a respectful regard for the memory of their Parents.”

C. Circulating the “Narrative” (after Funds Had Been Raised)

As detailed in the section, II. Textual and Editorial Issues, long after funds had been raised in aid of the Green children, Dorothy’s “Narrative” was read and copied by family members and friends, and from very early on, she was urged to publish it. Dorothy’s response to Catherine Clarkson’s encouragement came in a letter dated 9 December 1810. It is worth quoting in full, as her famous refusal—“I should detest the idea of setting myself up as an Author”— is often taken out of context and misconstrued: ‘My dear Friend I cannot express what pain I feel in refusing to grant any request of yours, and above all one in which dear Mr Clarkson joins so earnestly, but indeed I cannot have that narrative published. My reasons are entirely disconnected with myself, much as I should detest the idea of setting myself up as an Author. I should not object on that score as if it had been an invention of my own it might have been published without a name, and nobody would have thought of me. But on account of the Family of the Greens I cannot consent. Their story was only represented to the world in that narrative which was drawn up for the collecting of the subscription, so far as might tend to produce the end desired, but by publishing this narrative of mine I should bring the children forward to notice as Individuals, and we know not what injurious effect this might have upon them. Besides it appears to me that the events are too recent to be published in delicacy to others as well as to the children. I should be the more hurt at having to return such an answer to your request, if I could believe that the story would be of that service to the work which Mr Clarkson imagines. I cannot believe that it would do much for it. Thirty or forty years hence when the Characters of the children are formed and they can be no longer objects of curiosity, if it should be thought that any service would be done, it is my present wish that it should then be published whether I am alive or dead.

Dorothy’s sensitivity to the children’s privacy trumps even the request of her dear friends, the Clarksons, and seems driven by concern that the orphaned children might be harmed, their story sensationalized.

Over thirty years after the deaths of George and Sarah Green, in 1839, Thomas De Quincey, a well-known author who had moved into Dove Cottage after the Wordsworths relocated, revisited the episode in his essay Recollections of Grasmere, which was first published as the September 1839 installment of his Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine series, “Sketches of Life and Manners; from the Autobiography of an English Opium Eater.”

De Quincey recollects that, after returning from a visit to the Lakes to Oxford in 1808, he received a letter from Dorothy “asking for any subscriptions [he] might succeed in obtaining, amongst [his] college friends, in aid of the funds then raising in behalf of an orphan family, who had become such by an affecting tragedy that had occurred within a few weeks from [his] visit to Grasmere.”

Alluding to Dorothy’s as-yet-unpublished “Narrative,” he describes how “Miss Wordsworth’s simple but fervid memoir not being within my reach at this moment, I must trust to my own recollections and my own impressions to retrace the story.”

De Quincey proceeds with a lengthy, embellished account filled with details of both the Greens’ death on the fells and of the children’s patient suffering that are not included in Dorothy’s account. It is not clear how he came by these details, though he did move to Grasmere in 1809, so it is possible he heard them from witnesses. Nevertheless, De Quincey transforms the narrative into melodrama. He describes how the Greens had been strongly warned against returning home via Langdale Fell, a point never mentioned in Dorothy’s account, and comments: “After this they were seen no more. They had disappeared into the cloud of death.” He also invents the mounting fears of the soon-to-be-orphaned Green children, imagining how “Every sound, every echo amongst the hills, was listened to for five hours, from seven to twelve.” Further adding a gothic flair to the tale, he writes, “Some time in the course of the evening—but it was late, and after midnight—the moon arose, and shed a torrent of light upon the Langdale fells, which had already, long before, witnessed in darkness the death of their parents.”

Dorothy, in contrast, describes the children patiently waiting, reasonably assuming their parents had stayed overnight in Langdale due to the weather. Whereas Dorothy’s account evidences a deep communal and human connection to the Greens, De Quincey’s treats this family catastrophe as an occasion for overwrought storytelling. At one point, in fact, he confesses to having entertained a party of American visitors “by conducting them through Grasmere into the little inner chamber of Easedale, and there, within sight of the solitary cottage, Blentarn Ghyll, telling them the story of the Greens.”

In other words, albeit decades later, her once-intimate friend De Quincey exploited the Greens’ fate much in the way Dorothy feared.

Dorothy’s account thus remains the most reliable account of this Lakeland tragedy, providing extensive details about the lives of the Green family before the death of the parents, the events surrounding their deaths, and the community’s response. In addition to being the most informative, it is the least romanticized of the records, and also the most poignant.

II. Textual and Editorial Issues

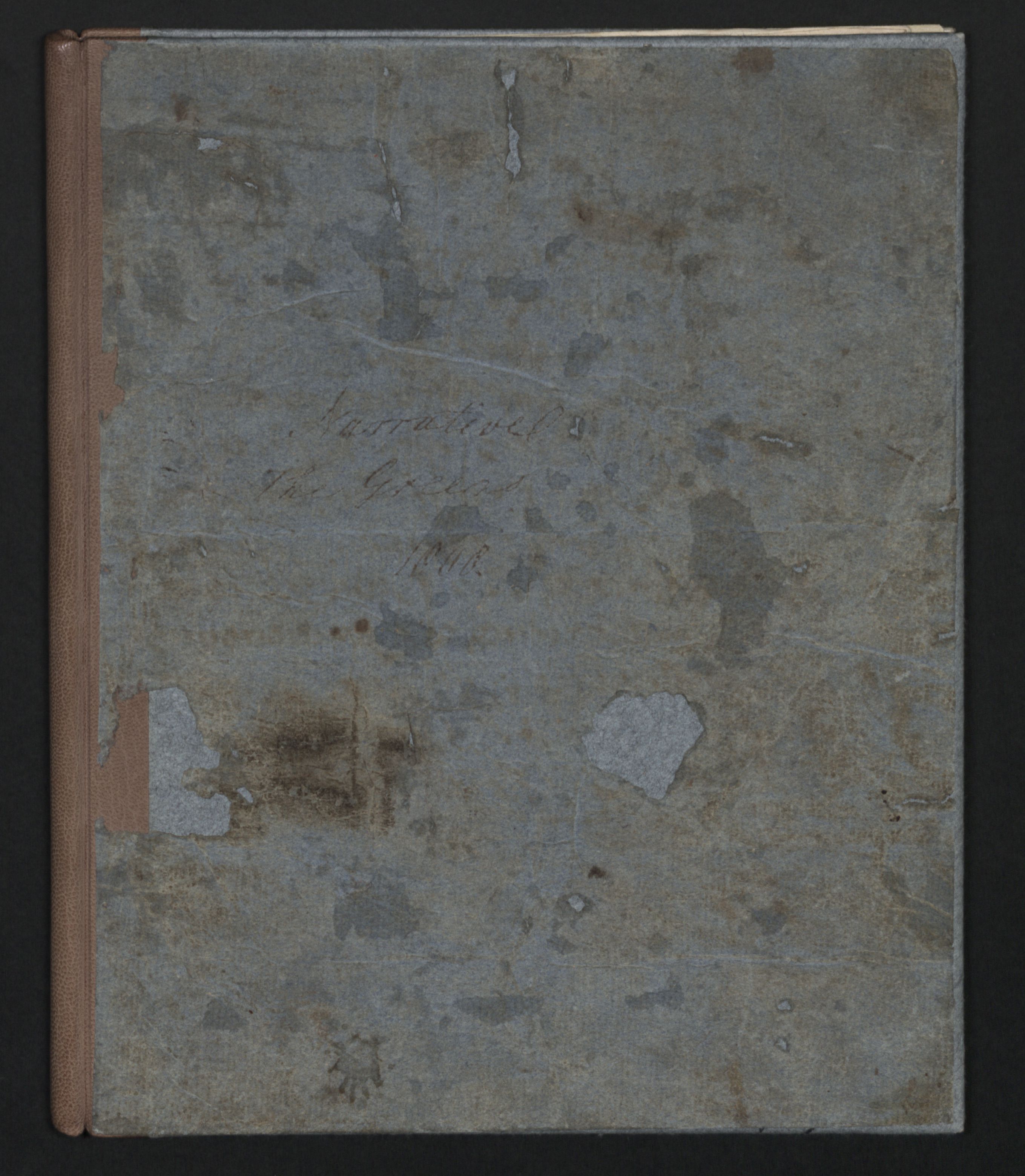

The diplomatic transcription of the “Narrative” that follows is taken from DCMS 64, a blue, paperbound notebook in the collections of the Wordsworth Trust. Written on the cover of the notebook, in Dorothy’s hand, is the short title “Narrative. The Greens 1808.” (see fig. 3). The notebook begins with a prefatory note by William, dated 11 May 1808, explaining that the narrative was “drawn up” by Dorothy at his request (fig. 1 in Diplomatic Transcription of the Greens Narrative (DCMS 64)). William adds that he “entreated that she would give a minute detail of all the particulars which had come within her notice,” as a full report would better answer “the end for which the account was written . . . viz. that of leaving behind a record of human sympathies, and moral sentiments, either as they were called forth or brought to remembrance” by the tragic deaths of George and Sarah Green in March. On the first page of the “Narrative,” Dorothy provides the full title as “A Narrative concerning George & Sarah Green of the Parish of Grasmere addressed to a Friend.” (see fig. 2). The notebook contains thirty leaves, and the page size varies slightly, averaging approximately 240mm x 190mm (h x w). The notebook appears to have been made by a stationer, as the paper board cover is original (fig. 2).

Figure 3. DCMS 64. Dorothy has written “Narrative the Greens. 1808” on the blue board cover. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

Dorothy’s “Narrative” fills the entire rest of the notebook now catalogued as DCMS 64. She paginated it from page 2 to the end of the “Narrative” on page 43. After a few blank leaves following the end of the main text, she added four pages of notes. As may be seen in figure 2, a representative page, the copy is largely fair, suggesting that she was probably working from a previous draft, but there are considerable revisions throughout. In our digital edition, the text is presented as a diplomatic transcription that respects as much as possible the text and layout of the original (including line, paragraph, and page breaks).

Dorothy’s handwritten revisions within DCMS 64 may be divided into three main categories:

- Those she seemingly made while drafting the original or shortly thereafter. All of these changes are minor and reflect immediate second thoughts.

- Those made in ink at a somewhat later date. Chiefly, these are cancellations of lines or passages like the aforementioned complaints about Mrs. North. She also cancels William and Mary’s names in one place, substituting “my brother and sister.” In another, she replaces “William” with “my brother.” Further, she softens some descriptions of the Greens that might have been perceived as negative. These revisions and cancels are often made with a noticeably darker ink.

- Those made in pencil, possibly later still. For the most part, these revisions are insubstantial, making minor corrections or simply recopying the same words (a practice seen in Dorothy’s other manuscripts). She does, however, add one substantial note in pencil, the final one, which recounts the tragic death of the villager Mary Watson (see note to page 38).

In total, there are five known manuscripts of the “Narrative.” Three are autograph copies, two of which are complete (DCMS 64 and British Library Add MS 41267) and one incomplete (DCMS 51). The remaining two (DCMS 167 and WLMSH/2/5) are transcriptions made by other hands, as described in the following paragraphs. All copies except the British Library autograph are held by the Wordsworth Trust. We have selected DCMS 64 as our copy-text because it is Dorothy’s personal copy, the one to which she returned to reread and make revisions. The handwriting is fair, with most of the revisions and cancels having been added later, as can be determined by the differences in ink and by the nature of the revisions, most of which appear to have been made to mask the identity of some of the individuals involved, for reasons of tact or clarity. (Such changes were typical of Dorothy, especially when she contemplated publishing her manuscript materials or sharing them with new audiences.) Dorothy also added notes to the end of the “Narrative” that relate to events that took place many years after 1808. If there had been a preceding draft, it has not survived.

The British Library (BL) copy (Add MS 41267), part of the Clarkson Papers collection, is almost entirely fair, written in a neat hand with very few revisions. Like DCMS 64, it is dated 4 May 1808, but it seems unlikely that Dorothy completed this copy on the same day as she did DCMS 64, meaning she likely just reproduced the date from DCMS 64. As the BL catalogue entry notes, Catherine Clarkson is probably the “friend” mentioned in the title and the original dedicatee of the narrative. At the end of a letter dated 9 February 1812, Clarkson writes to Dorothy, “Don’t forget your promise of giving me a copy of your Narrative in your own hand-writing.”

Clarkson had certainly read a copy of the “Narrative” earlier, as is evidenced by her letter of 9 December 1810 urging Dorothy to publish it, but perhaps she never had her own copy prior to 1812. The paper in the BL manuscript of the “Narrative” is watermarked 1808; however, this tells us only that the text was copied sometime after 1808—Dorothy might have had the paper for some time. So, it seems likely that the BL manuscript was made after Clarkson’s 1812 request, on paper from 1808, or that Dorothy simply sent Clarkson a copy she had made earlier. Some, but not all, of the revisions to DCMS 64 are duplicated in the BL manuscript, suggesting either that some revisions to the notebook were added after the BL copy had been made or that Dorothy did not wish to retain some of the revisions in the copy.

The only surviving autograph version of the “Narrative” besides DCMS 64 and the BL copy is an excerpt in DCMS 51, a miscellany in which Dorothy copied various poems and narratives. After including William’s inscription and four pages of the “Narrative,” it ends mid-sentence in a paragraph found in the middle of page 5 of DCMS 64. Like the BL copy, the DCMS 51 version appears to have postdated DCMS 64. It includes only one small correction, made on the first page in the course of copying. It does not include any of what appear to be the later revisions to DCMS 64.

Our edition notes any textual discrepancies between the two complete surviving autograph versions (DCMS 64 and the BL/Clarkson copy). Assuming that DCMS 64 was Dorothy’s copytext for the BL version, she made minor revisions in the process of transcribing.

One of the two complete contemporaneous copies of the “Narrative” in other hands, DCMS 167, was, according to a note at its end, “transcribed by Miss Fletcher now Lady Richardson.” Mary, Lady Richardson (1802–1880) lived in Easedale for several years. Her mother, Mrs. Mary Fletcher (1770–1858) had visited the Lakes on several occasions and in 1839, with the help of William Wordsworth, had purchased, with her husband, Lancrigg Farm in Easedale. Her youngest daughter, Mary, who transcribed the “Narrative,” lived at the farm with her parents until her marriage in 1847. It is likely that her interest in the Greens’ story came about because the family’s residence was near the cottage where the Greens had lived (and which remains there today). As the Fletchers did not move to Easedale until 1839, the “Narrative” was likely not copied until some time later, suggesting ongoing interest in the story. The other copy, WLMSH/2/5, was transcribed by Mary Wordsworth’s sister Sara Hutchinson. The year in which this transcript was made is not known.

The number of extant copies demonstrates the significance the “Narrative” held for the Wordsworths and their social circle, as a document meant to record an important incident in the life of the village but also to travel widely. In 1839, De Quincey reports his understanding that the “Narrative” “went into the hands of the royal family; at any rate, the august ladies of that house (all or some of them) were amongst the many subscribers to the orphan children.”

The highest number of complete manuscript copies of a work by Dorothy that survives is five, for the Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland, A.D, 1803. However, the “Narrative” is a close second with four complete manuscripts and one partial copy. In contrast, Dorothy’s Journal of a Tour of the Continent, 1820 survives in only a single copy, as is the case with her Grasmere journal notebooks, which were evidently not meant to be shared outside of the household.

A November 1850 letter from Mary Wordsworth to her sister-in-law Mary Monkhouse Hutchinson establishes that the “Narrative” was still being circulated and copied four decades after its composition. Midway through this letter, the then-80-year-old Mary Wordsworth asks whether Monkhouse’s daughters, Elizabeth and Sarah, had “ever beg[u]n to copy the Green’s Narrative and if so what they did with it.” Apparently, Fanny Wordsworth, wife of William Jr., had recently reported, “Eliz. was about it when she was at Carlisle, and Sarah talked of doing it at the Cooksons.” Since, as Mary Wordsworth explains, the Green “family have applied again for it,” her recently deceased husband’s long-time clerk, John Carter, “is ready to make them a Copy, if he hears one is not in forwardness.”

The copy eventually sent to the Greens, the present whereabouts of which are unknown, was passed down from John Green—a seven-year-old at the time of his parents’ death—to his granddaughter, who wrote about her possession of it in a letter to the Wordsworths’ descendants.

Dorothy would have been highly gratified to have known of the Greens’ fondness for her “Narrative,” for she had always believed that those who had personal knowledge of the subjects of her writing would be most appreciative of it. This philosophy of writing was one of the reasons she published so little of what she wrote and sometimes struggled to revise her work (like the Scotch tour) to ready it for a wider, public audience. As she told Catherine Clarkson, she supported the publication of the “Narrative” after the Green children were grown and out of danger of exploitation, and so would probably have approved of Ernest de Sélincourt publishing the first print edition of the “Narrative” in 1936. Though much more time had passed than the “thirty or forty years” Dorothy had asked for it to remain private, she had no objections, as noted previously, to its publication, provided that “it should be thought that any service would be done.”

William, in his prefatory inscription to the “Narrative,” makes explicit what this service is: “that of leaving behind a record of human sympathies, and moral sentiments, either as they were called forth or brought to remembrance, by a distressful event.”