II. Textual and Editorial Issues

A. Manuscript Witnesses and Related Primary Sources

B. Editorial Principles

C. Dorothy’s Account vs. William’s Guide to the Lakes

D. Post-Guide Editions of the Text

I. Contexts

A. Overview

This section of our edition features Dorothy Wordsworth’s account of climbing Scafell Pike,

England’s highest mountain, in 1818. A revised and abbreviated version of the text appeared under her brother William’s name in his Description of the Scenery of the Lakes in the North of England (1822), the first stand-alone edition of the work, now commonly known as Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes (figs. 5.1 and 5.2).

Since subsequent editions of William’s Guide continued to present her description of the ascent as his, Dorothy’s authorship was not broadly acknowledged until 1941 when Ernest de Sélincourt included the full text in his important edition of her journals.

In the Guide, William introduced Dorothy’s narrative as an “extract from a letter to a Friend.”

While this attribution was technically accurate, as Dorothy did send the account in a letter to their mutual friend, the Reverend William Johnson, William never mentioned that the source was his sister’s letter, leaving readers to assume that he was its author. Later writers of travel books, drawing on the Guide, enthusiastically quoted Dorothy’s language as if it were William’s and supposed that he had made the climb. For over a century, then, devotees of the poet intent on emulating his ascent remained unaware that it was, in fact, Dorothy’s footsteps that they were retracing.

Figure 1. Title page from William Wordsworth’s Description of the Scenery of the Lakes in the North of England. (Courtesy: Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library)

Figure 2. Selection from the book’s table of contents, "Ascent to the Top of Scawfell." (Courtesy: Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library)

Dorothy’s description of her ascent, which De Sélincourt called “Excursion up Scawfell Pike,” is remarkable for at least two related reasons. First, it is a landmark in the history of British mountaineering—one of the earliest reports of a recreational climb of Scafell Pike (3,209 ft., or 978 m) and the first by a woman.

Second, it captures an aspect of Dorothy’s life that has sometimes been overlooked. Dorothy Wordsworth was a prodigious walker—this fact is well known—but her pioneering achievements as a mountaineer have insufficiently shaped the public’s memory of her.

“Excursion” helps us reimagine Dorothy on the fells, representing one of her most dramatic walks in the vibrant prose for which she is famous.

Of course, recovering Dorothy’s place in mountaineering history requires bringing her “Excursion” out of the shadow of her brother’s writing. One admirer subtly pointed this out in 1855, the year of Dorothy’s death. In a letter to the editor of the Kendal Mercury, venerable mountain guide Jonathan Otley hinted that there was more to tell about the now-famous Scafell Pike adventure: “The story of the ascent of Scawfell, in Wordsworth’s Guide, said in some former editions to be extracted from a letter to a friend; and in the last edition from a letter by a friend, is well told, and is good as far as it goes; but it might have been improved by a prefatory introduction, and extended by an appendix.”

Our introduction and editorial apparatus should perform the record-expanding services that Otley imagined, restoring a historic experience and its documentation to the rightful owner: Dorothy Wordsworth.

B. Background Story

On Wednesday, 7 October 1818, Dorothy Wordsworth (age 46) and her friend Mary Barker (age 44) climbed Scafell Pike, the highest mountain in England. They were joined by a shepherd-guide (John Allison, Barker’s neighbor), a porter, and Barker’s maid (Agnes)—none of whom were named in Dorothy’s account of the adventure.

They walked an ambitious nine-mile loop that took the better part of a day: Dorothy reports setting out in the morning and finishing as the first stars appeared over Borrowdale.

For Dorothy, this hike was the culmination of a season spent among brilliant associates. Her old acquaintance William Wilberforce, the statesman and abolitionist, had arrived in the Lake District with his family in late August 1818 and spent most of September at Rydal to be near the Wordsworths. Sir George and Lady Beaumont, dear friends and prominent art patrons, also visited Rydal in September.

In early October, the Wilberforces decamped to nearby Keswick, where Dorothy and the Beaumonts soon joined them. (William Wordsworth, meanwhile, was occupied with political business).

Learning of this gathering in Keswick, Mary Barker invited the whole group to dine at her new home in Rosthwaite, Borrowdale, six miles to the south (fig. 5.3).

Figure 3. The Scafell Hotel in scenic Rosthwaite, Borrowdale, originally the home of Mary Barker. It has long been a launching point for walks in the mountains. (Photo: Paul Westover, October 2018)

A writer, artist, and music teacher, Mary Barker had lived next door to the Robert Southey family in Keswick between 1812 and 1817. She soon became intimate with the larger “Lake Poet” circle, and in 1814, Dorothy described her to Catherine Clarkson as the epitome of “Generosity, Frankness, Sincerity, and perfect disinterestedness.”

Dorothy also mentioned her friend’s “warm temper” and “disdain [for concealing] her opinions.” Barker was passionate, funny, and independent.

Though impractical,

relatively isolated, and built alongside a flood-prone branch of the River Derwent, Mary Barker’s new home was nonetheless ideal for hosting friends who shared her taste for mountain scenery.

Dorothy went there on the morning of 5 October, possibly to help with preparations for the dinner. Then, on 6 October, the Wilberforce entourage and the Beaumonts made their way into Borrowdale “with store of provisions,” while Barker “provided vegetables, etc.”

In a period famous for its “immortal” dinners, this was a gathering worthy of remembrance.

In the course of conversation, the Wilberforces expressed their intent to ride up Skiddaw (3,054 ft., 931 m), the far-famed mountain overlooking Keswick, on the following morning, and the Beaumonts pledged to accompany them. Wilberforce would be revisiting an ascent he made years earlier while touring the Lakes as a young man. Accordingly, most of the visitors returned to Keswick for the night, looking forward to their outing, but Dorothy stayed at Rosthwaite. She and her host settled on their own hiking plan. Thus, as Dorothy reports, she and Mary Barker summited Scafell Pike on the same day their friends explored Skiddaw, 14 miles to the north. The Skiddaw excursion was less ambitious than the Scafell Pike ascent; still, as Wilberforce was in his late 50s and the Beaumonts in their 60s, none of them in perfect health, we should admire the spirit of this group as well—not least because they got a good wetting in the rain.

Meanwhile, from high in the mountains above Borrowdale, Dorothy and Mary, enjoying comparatively mild weather themselves, saw rainbows over Skiddaw and felt grateful that the weather had eventually cleared for their friends.

Dorothy and Mary Barker did not at first aim to climb Scafell Pike—their original goal was to ascend Esk Hause (2,490 ft.), a high pass that on a clear day would afford excellent views of the surrounding peaks and valleys. Barker, of late “an active climber of the hills,” had recently been to Esk Hause and was eager to share the “magnificent prospect.”

However, when the friends arrived at the pass, they decided to press on. As Dorothy reports, their “spirit of enterprise” did not fail, and they climbed where, so far as we can tell, few other recreational walkers had been.

Because it was a fine day, they could see for miles in every direction. Heart-stopping views like this were relatively uncommon in an age unfamiliar with air travel and satellite imagery. However, Dorothy characteristically noticed close-range features as well as the vast panorama. She observed, for instance, that the rocks were “covered with never-dying lichens . . . adorn[ed] with colours of the most vivid and exquisite beauty.” She also observed the extreme silence of the summit, having had the sound of mountain streams in her ears for much of the ascent.

Despite her emphasis on accurate description, Dorothy explored the limits of her perceptions. Looking out from the mountain to the sea (over 12 miles away), she supposed she saw a ship. “Is it a ship?” her smiling guide asked. Barker quickly supported Dorothy’s conclusion: “A ship, yes, it can be nothing else.” However, a moment later, the “ship” had become a horse, for in fact the friends had been watching a cloud. Dorothy enjoyed this joke on herself, resolving to remember it when she was “again inclined to positiveness.” Like many great Romantic texts, Dorothy’s “Excursion” reminds us that what we see depends to some extent on prior experience, perspective, and imagination.

Reading Dorothy’s account, one gets the impression that she was pleased with herself, and rightly so. She remarks upon the “continuance of that vigour of body, which enabled me to climb the high mountain, as in the days of my youth” and reports that she and Barker each dashed off a triumphant letter to Sara Hutchinson

from the summit. (It is remarkable to think of them carrying pens, paper, and ink, if not also something to write on—no wonder they secured the help of a porter!) A week later, Dorothy wrote briefly about the experience to her old friend Jane Marshall,

and a week after that she composed the longer, more circumstantial letter to William Johnson that forms (indirectly, as explained in our textual and editorial section) the basis of our edited text, speaking of the “feat” she and Barker had performed and aptly calling it an “uncommon performance.” Then, before mailing the letter, she copied it into one of her notebooks for preservation. She and her companion had broken with social convention and done something worth remembering and sharing. Part of their enjoyment, clearly, was writing about it.

C. Afterlives: Dorothy’s Mark on the Mountains

When Dorothy Wordsworth climbed Scafell Pike, this mountain—which had been proven to be England’s highest peak by Joseph Banks’s Trigonometrical Survey in 1790

—was not yet on the beaten tourist trail. While highland walking had increased in popularity in recent years, the vast majority of Lake District pedestrians tended to stick to well-established routes around the central valleys.

Maps of the mountains included limited detail, and those enterprising tourists who did explore them generally depended on local guides. In subsequent decades, of course, mountain walks became common practice and guidebook staples. Scafell Pike in particular became a rite of passage for Lakeland peak-baggers. Dorothy and her friends played a part in bringing about this shift, though relatively few people knew this.

The perennial challenge in studies of Dorothy Wordsworth has been her tendency to disappear, a propensity abetted by William’s habit of absorbing her work and by models of literary history that have undervalued the kinds of writing she did and the methods she used to share it. Readers often locate her influence indirectly, in poems of William’s that rework her journal entries, in letters that reveal her collaboration, and so forth, but except on occasions when William mentions her directly or includes her verses in his collections, it is often difficult to say, “There it is—there’s Dorothy’s mark.”

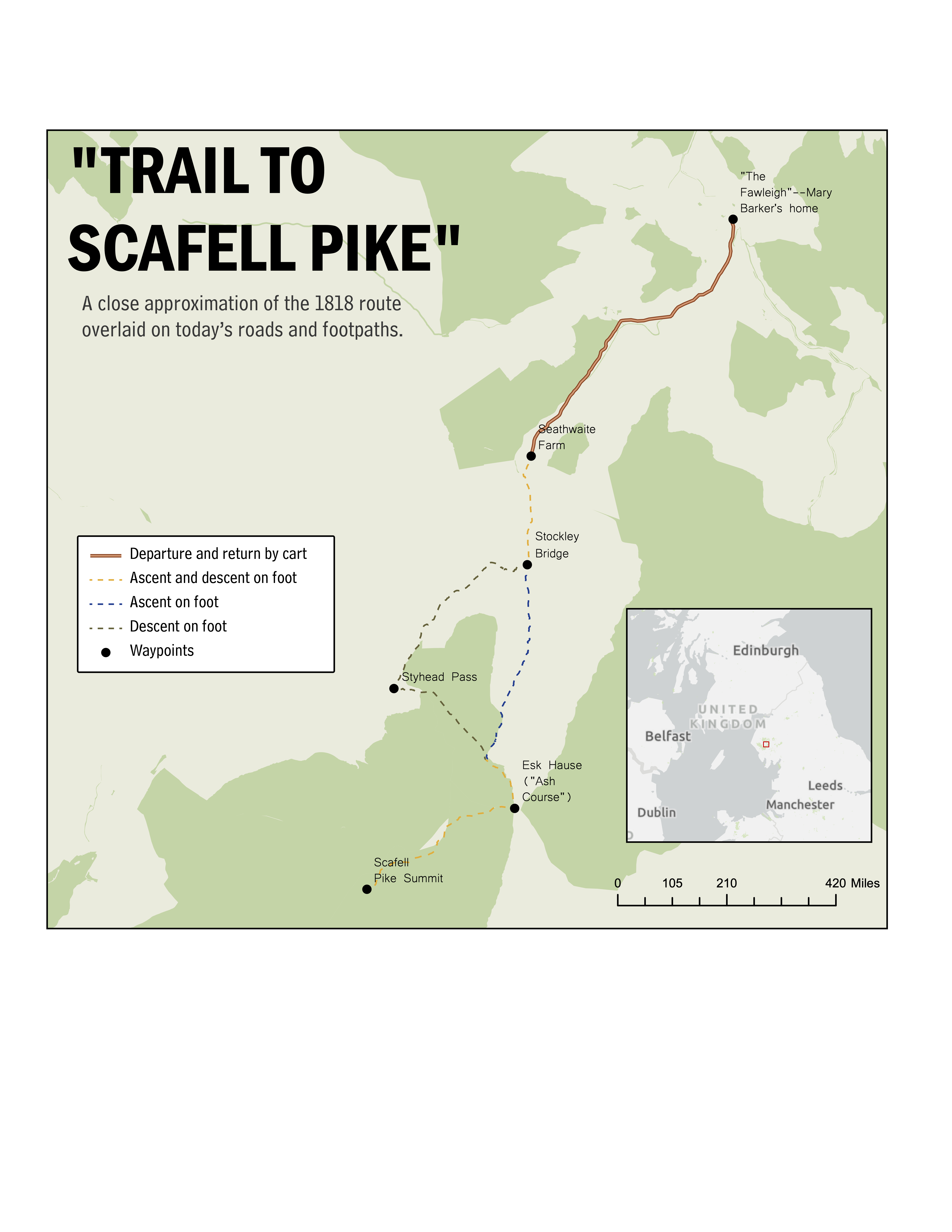

Yet Dorothy’s mark is visible on England’s highest mountain, where walkers have unwittingly followed her footsteps for two centuries now. Almost literally, you find those footsteps inscribed on the landscape in the form of trails (fig. 5.4). To be sure, many aspects of trail-making are determined by practical factors unrelated to literary history, but Dorothy’s Scafell Pike route has endured partly because of her writing’s intersection with the nineteenth century’s multiplication of maps and guidebooks.

Figure 4. The route taken by Dorothy Wordsworth, Mary Barker, and their companions on 7 October 1818, ascending from Seathwaite via Grains Gill and returning by way of Sty Head. This loop remains easily traceable on maps today. (Created by Paul Westover and Teresa Gomez, Brigham Young University)

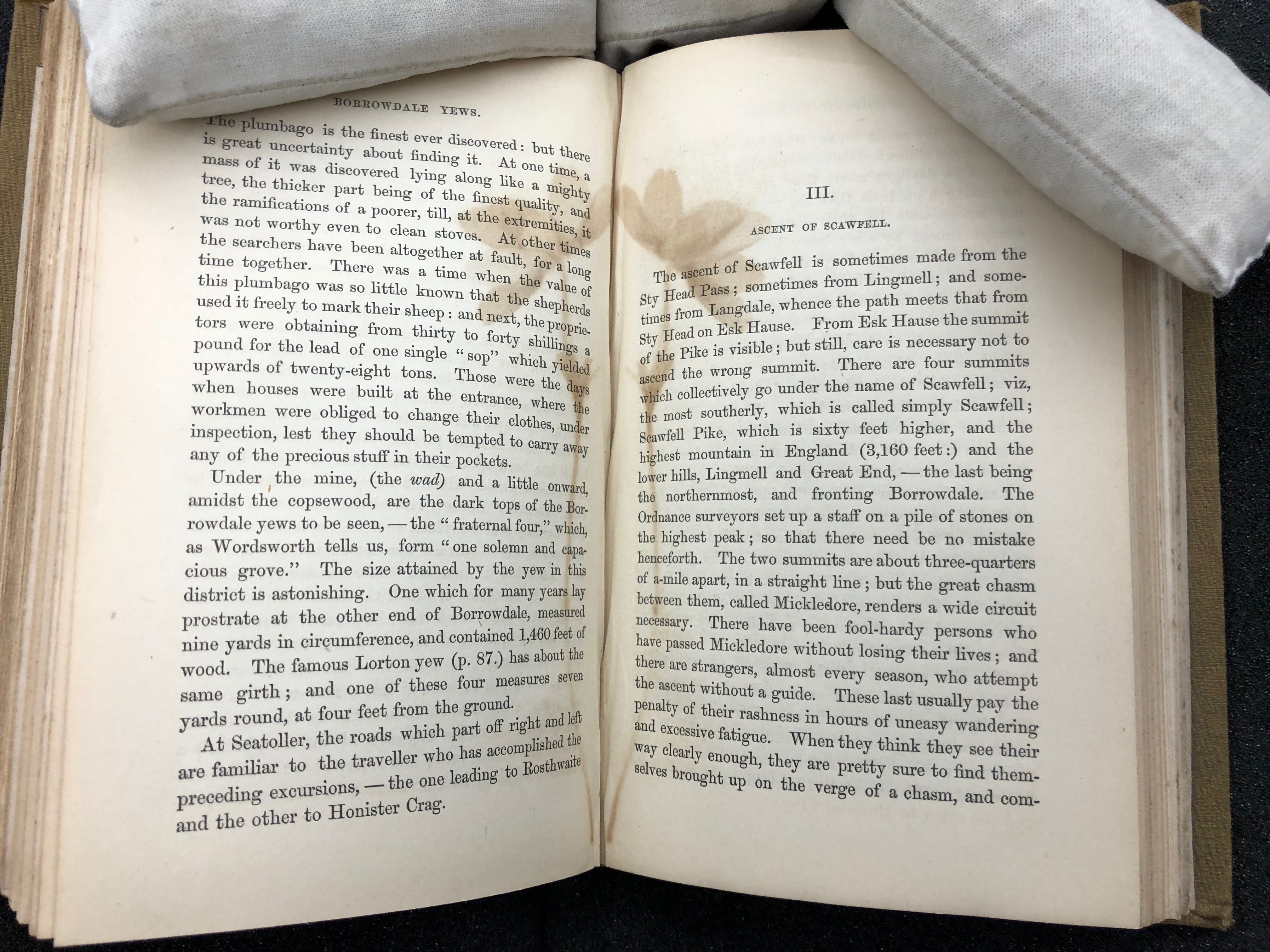

Dorothy observed of Scafell Pike’s rocky summit, “No gems or flowers can surpass in colouring the beauty of some of these masses of stone which no human eye beholds except the shepherd led thither by chance or traveler by curiosity; and how seldom this must happen!”—seldom because, as she noted, sheep would find little in the rocks to eat, and because recreational fell-walking there was still in its early days. However, once Dorothy’s letter found its way into William’s Guide, a transformative process began. By incorporating Dorothy’s ascent narrative (not far removed in genre from accounts that would later appear in Alfred Wainwright’s books and on trekking websites), the Guide made it a permanent part of the tourist literature and encouraged readers to imagine and undertake their own mountain ascents.

Just as importantly, William’s Guide provided material that would be recycled by other travel writers. Numerous Lakeland guidebooks of the Victorian era, including Harriet Martineau’s famous Complete Guide (fig.5.5), lingered on the Guide’s description of climbing Scafell hike. Normally, writers attributed the description to William, if they attributed it at all, but in doing so they enshrined Dorothy’s descriptive language and itinerary.

Figure 5. The Scafell Pike section of Martineau’s Complete Guide to the English Lakes (1855 pocket edition), which quotes extensively from Dorothy’s account by way of William’s. Note the imprint from a pressed flower, which suggests that this was once a favorite section of the volume’s owner. On the following page, Martineau writes, “As far as what is seen from [the peak], the best service to the stranger is still to copy portions of that ‘Letter to a friend’ which Mr. Wordsworth published many years ago, and which is the best account we have of the greatest mountain excursion in England” (138). (Courtesy: Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library)

The transmission process continued across many decades, as Dorothy’s (unacknowledged) observations were reprinted, quoted, and remembered by authors of various publications. Their influence reverberated even as far as Wainwright, the patron saint of latter-day Lakeland fell-walkers, who offered his own endorsement of Dorothy’s path in 1960: “Of the many routes of approach to Scafell Pike,” he wrote, “this, from Borrowdale via Esk Hause, is the finest.”

A few pages earlier, he specifically recommended the loop Dorothy and her friends followed—ascent via Grains Gill, descent via Sty Head. He might have done this coincidentally, but probably not; he knew Wordsworth’s Guide.

Hardwicke Rawnsley, writing in Literary Associations of the English Lakes (1894), captured both the reach and the essential irony of the reception history of Dorothy’s “Excursion.” Having quoted approvingly from the Scafell Pike section of the Guide and smiled over its observation (by then quaint) that few travelers summit that mountain, he concluded, “It may well be that never shall we witness such storm-grandeur as it was Wordsworth’s lot to witness when, having climbed hither on a still autumn day, he was bade by his shepherd guide not to linger, for a storm was coming.”

Of course, William Wordsworth never did witness that storm-grandeur—in fact, he never climbed Scafell Pike at all, so far as records can tell. Rawnsley, like many others, assumed that he had, and his aim was to emphasize that modern pilgrims might stand where the poet had stood. After all, as Rawnsley said, “the wanderer up Borrowdale and the mountains in its vicinity” will always “move” in “the company of chosen spirits.” But which spirits? In the minds of many, the company has always worn trousers, but we hope our edition helps readers correctly imagine skirts and bonnets in the party.

The 2018 bicentennial of Dorothy’s Scafell Pike adventure offered a unique occasion to promote awareness of the “Excursion” and its place in history. A cluster of commemorative projects, including an award-nominated exhibition at the Wordsworth Museum in Grasmere, This Girl Did: Dorothy Wordsworth and Women Mountaineers; a series of related lectures, magazine articles, and interviews; reenactments of the Scafell Pike and Skiddaw ascents; and a documentary film, combined to make this text more visible than perhaps it has ever been.

This digital edition further aids in this effort, not only by celebrating Dorothy’s descriptive prose but also by providing illustrations that will help readers visualize the route she and Mary Barker took on 7 October 1818. In particular, we recommend visiting our Story Map, a multimodal reconstruction of that day, complete with a 3D map, photographs, and videos. We trust that these resources help restore “Excursion up Scawfell Pike” to the honorable place it deserves in the canon of Dorothy’s writings—and in the tradition of ascent narratives generally.

A. Manuscript Witnesses and Related Primary Sources

Although De Sélincourt categorized Dorothy’s Scafell Pike account with her journals, it is not a diary entry per se. This genre question deserves consideration, for some of the text’s character depends on its material forms, its circulation, and its audiences.

In conception, Dorothy’s account emerged from a cluster of letters—including, we presume, the lost one she wrote to Sara Hutchinson on top of the mountain. The earliest surviving record of her ascent is her letter to Jane Marshall, dated 14 October 1818, which reads like a seed draft for the expanded report she would pen a week later. Dorothy expresses continued admiration for William Wilberforce (“There never lived on earth, I am sure, a man of sweeter temper”) and recaps the lively 6 October dinner at Rosthwaite. “The next day,” she continues, “which was one of the finest of the year, I ascended Scaw Fell from Seathwaite with Miss Barker—and never before did I behold so sublime a mountain prospect.” Grateful for the weather they enjoyed, she reports, “Our Guide, who is a Shepherd of Borrowdale, turning his eyes thoughtfully round when we were on the pinnacle of Scaw Fell, said ‘I do not know that ever in the whole course of my life, I was at any season so high upon the mountains on so calm a day.’ There was not a breath of wind to stir the very papers which we spread out with our food, when we ate our dinners on that commanding eminence.” Some of this language would reappear almost verbatim in Dorothy’s final treatment of the subject.

The experience of climbing the mountain obviously remained vivid in Dorothy’s mind. Eager to share it at length, she wrote on 21 October to the Reverend William Johnson, former curate and schoolmaster in Grasmere (1811–1812), who had since taken up an important teaching post in London. The original of her letter has been lost. Fortunately, two copies survive, and these are our manuscript authorities for “Excursion up Scawfell Pike.”

The most complete extant manuscript is Dorothy’s own backup copy: as noted previously, she transcribed her letter to Johnson into a hand-sewn notebook, which is now catalogued as Dove Cottage Manuscript (DCMS) 51 (fig. 5.6). Similar to DCMS 120, which preserves Dorothy’s poetry, DCMS 51 collects literary efforts that she valued. “Excursion up Scawfell Pike” is its final item (fig. 5.7). It features both Dorothy’s edits in ink and various pencil marks, possibly by William, which move the text in the direction of his Guide.

Besides the obvious merit of being written in Dorothy’s own hand, this manuscript also includes two important notes at the bottom of the last page: “October 21st 1818” (confirming the composition date of the Johnson letter) and “Went up Scaw Fell on Wednesday the 7th October-1818.”

Figure 6. The cover of DCMS 51, the notebook that contains Dorothy’s copy of the Johnson letter. The cover inscription reads “Dorothy/Wordsworth/Rydal Mount.

Figure 7. The beginning of Dorothy’s “Scawfell” account in DCMS 51

The second surviving manuscript, described hereafter as the Kenyon Transcript, is written in an attractive, unknown hand on paper watermarked 1817 (fig. 5.8). At once a letter in its own right (addressed to “Miss Hutchinson” in Wales) but otherwise businesslike, with no conventional gestures of greeting or conclusion, it is actually an incomplete copy of Dorothy’s letter to Johnson. It is dated “October, 1818” and bracketed entirely within quotation marks. It begins, “I must inform you of a feat that Miss Barker and I performed on Wednesday the 7th of this month.” In short, it omits material that takes up more than a page of Dorothy’s notebook version, including her introduction of Mary Barker and her description of the dinner at Barker’s home. As Simon Bainbridge summarizes, it “edits out the first part of the original letter to focus on the ascent narrative.”

Figure 8. The first page of the Kenyon Transcript, written in an unknown hand. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

While DCMS 51 is longer and arguably more authoritative than the Kenyon Transcript, much of its final page has been torn out and lost (fig. 5.9). Therefore, at least for the closing section of Dorothy’s account, the Kenyon Transcript is essential.

Figure 9. The final two pages of DCMS 51. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

Furthermore, the Kenyon Transcript may match the original Johnson letter more closely than the DCMS 51 copy in some respects. We suggest this because DCMS 51 shows edits for style and economy that the Kenyon Transcript does not include. Derived directly from the Johnson letter (or from yet another copy that has not survived), the Kenyon Transcript likely retains many original readings, despite errors in copying. Additionally, the transcript includes a final paragraph that Dorothy omits in DCMS 51: “I believe that you are not much acquainted with the Scenery of this Country, except in the Neighbourhood of Grasmere, your duties when you were a resident here, having confined you so much to that one Vale; I hope, however, that my long Story will not be very dull; and even I am not without a further hope, that it may awaken in you a desire to spend a long holiday among the Mountains, and explore their recesses.” No doubt this invitation was part of the original letter to Johnson, but Dorothy saw no reason to copy it for her own records.

The Kenyon Transcript complicates the view that Dorothy’s text was never published except as part of William’s Guide to the Lakes. True, “Excursion up Scawfell Pike” was never printed as Dorothy’s during her lifetime, but it seems to have enjoyed a lively public (or at least semipublic) existence in handwritten forms, moving among family, friends, and associates.

Dorothy did write for an audience. By revealing some of her circuits of communication, the Kenyon Transcript helps us guess at the significance of “Excursion” for both its writer and her friends and admirers. For more on the Kenyon Transcript, please see the appendix to our diplomatic transcription.

In addition to the missing Johnson letter, the lost letters Dorothy and Mary Barker wrote to Sara Hutchinson from Scafell Pike would surely round out our understanding of 7 October 1818. Did these summit posts recall another famous “Scawfell letter,” written to the same Sara by Samuel Taylor Coleridge 16 years before on the neighboring peak?

We can only speculate, but it is not hard to imagine Dorothy recalling Coleridge’s exploit. Her “gift for drawing into the present all the wealth of past memories” surely applies to this text as it does to others.

If the missing on-the-spot letters ever surface, we may have more details to enrich our story and help us better understand why the Kenyon Transcript was mailed to “Miss Hutchinson.”

B. Editorial Principles

Our annotated and illustrated reading text is based primarily on DCMS 51, with minor emendations indicated in notes and the shift to the Kenyon Transcript (where DCMS 51 is torn) clearly indicated. Our emendations reflect the fact that certain conventions that today’s readers take for granted were not fully standardized in the early nineteenth century. Like other editors of Romantic-era writing, we have tried to balance reading convenience with preserving our text’s historical character.

Insofar as possible, we preserve Dorothy’s paragraphing, though her indentations vary and her intentions can be hard to discern. Dorothy’s underlined words are set in italics. Her ampersands are converted to and, and her occasional abbreviations are expanded—for example, “Sir G. and & Lady B.” to “Sir George and Lady Beaumont.” Capitalization is largely standardized, though we retain some instances in which Dorothy seems to capitalize common nouns for emphasis. We also retain Dorothy’s spelling.

Admittedly, any regularization may obscure important ambiguities or idiosyncrasies in the text. Some readers may wish to consult the original manuscripts to study Dorothy’s frequent and varied uses of dashes, as such marks either disappear in our reading text or appear uniformly as em dashes. Others may simply crave more antiquarian flavor. Fortunately, our digital edition will include page images of the two manuscript sources as well as diplomatic transcriptions, allowing readers to make their own judgments. In today’s “versioning” culture of editing, made convenient by technology, readers can generate their own ideal texts.

C. Dorothy’s Account vs. William’s Guide to the Lakes

Though based on DCMS 51, the version of “Excursion” that appears in William’s 1822 Guide simplifies Dorothy’s textual chronology and removes all dates, as if aiming to make the account timeless. It introduces various minor revisions.

However, the most obvious difference between Dorothy’s manuscript and the adaptation is the latter’s reduced length. William’s version includes approximately 1,205 words, whereas Dorothy’s original runs over 2,500. Unsurprisingly, Dorothy’s text is richer. The Guide’s main editorial tendency is to make Dorothy’s narrative less personal. In the manuscript, Dorothy begins by recording the visits of the Beaumonts and Wilberforces and by introducing Mary Barker—that is, by assembling her cast of characters. All of this social context disappears in the Guide. Thus, when the Guide reports, “Having left Rossthwaite [sic] in Borrowdale . . . we ascended,” readers have little sense of who “we” might be. In Dorothy’s manuscript, readers find friendship, personality, wonder, and humor, all shaping an expedition organized by two intrepid women. In William’s abridgment, readers mainly encounter landscape visions that might be comparable with those afforded by the Alps.

After reading William’s version, one knows nothing of the occasion that prompted the mountain walk and finds no sign that any women were involved.

What might Dorothy’s feelings have been about supplying this text for William’s Guide? We have a few key facts to consider. First, Dorothy was part of the project from the start. Back at the time of Select Views (1810), the first version of what became the Guide, William asked Dorothy to finish some of the writing when the work became “irksome” to him.

Meanwhile, Dorothy opined that William might repurpose Select Views, create his own guide to the Lake District, and find the product more lucrative than his “higher [poetic] labours.”

William eventually took her advice by including Select Views material in his 1820 River Duddon volume. This experiment resulted in encouraging sales and reviews, so issuing a stand-alone guidebook seemed like a logical next step. However, for this purpose, William likely sensed that his text needed some padding out.

Happily, he had promising material on hand in the form of Dorothy’s notebook and its copy of the Scafell Pike letter. Dorothy was fond of this autobiographical piece, which she had bound with other specimens of her best work (DCMS 51). She was probably willing—perhaps even pleased—to see it in print, even if it would appear in truncated form. Perhaps William transformed it for his own ends, but we should keep in mind the likelihood that Dorothy wanted him to use it and even preferred that he remove personal details about her and her friends. Indeed, she may have assisted with the edits.

The Guide was an important effort in favor of the family economy, and Dorothy supported this endeavor as she had so many others.

Readers must decide for themselves about the ethics of William’s borrowing, an issue that has been addressed repeatedly in studies of the Wordsworths but perhaps not sufficiently with respect to “Excursion up Scawfell Pike.” This instance of appropriation seems unique in scale and significance, as William tacitly takes credit not only for Dorothy’s writing but also for her physical accomplishment. Might it not have been a simple matter for William to describe the account as “an extract from my sister’s letter to a friend”? Nonetheless, we have no evidence that Dorothy objected to his editorial sleight of hand. Lucy Newlyn’s observation, offered in a different context, may apply in this situation: “Dorothy’s preference was always for an anonymous role in their collaboration, but this need not be read as a sign that she believed herself inferior. . . . Her labour was not alienated, and she knew her gifts to be greatly valued.”

In any case, the Guide’s incorporation of Dorothy’s Scafell Pike ascent must have been thought a success by all concerned. The 1822 Guide sold well, and then, in the 1823 edition, another gem from Dorothy’s notebook (DCMS 51) was added: her account of an 1805 walking tour around Ullswater. This meant that Dorothy’s presence in the Guide grew as the project evolved. We do not know precisely how many words she contributed in 1810 or 1820,

but in 1822, she generated at least 1,200 words out of the total 29,800 (about 4 percent), and in 1823, at least 4,446 words of 35,300 (13 percent). The placement of her offerings was also important, since her two “excursions” became the final, climactic section of the book.

D. Post-Guide Editions of the Text

For over a century, the survival of Dorothy’s “Excursion” in print depended on the popularity of William’s Guide. William Angus Knight did not include it in his 1897 edition of Dorothy’s journals or his 1907 Letters of the Wordsworth Family. Consequently, as noted previously, its full public introduction had to wait for the appearance of De Sélincourt’s 1941 Journals (vol. 1).

De Sélincourt’s edition, with its brief but valuable introduction, remained the standard for years.

In 1970, the text appeared in the revised Oxford Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth (vol. 3, Middle Years II, 1812–1820). This resource correctly reframed the text as a letter ( “D. W. to William Johnson” ); however, some information it provided was misleading. The editors of that volume, Mary Moorman and Alan G. Hill, cited as their manuscript authority “WL transcript [possibly in John Carter’s hand].”

Either that document has been lost or, more likely, the editors meant to describe what our edition calls the Kenyon Transcript, which is definitely not in John Carter’s hand. Moreover, the editors did not faithfully follow that source. Instead, they largely adopted De Sélincourt’s text from Journals, though they did add one sentence, Dorothy’s final invitation to come explore the mountains.

A few years later, W. J. B. Owen and Jane Worthington Smyser provided a more reliable and thoroughly annotated version of the Scafell Pike “Excursion” as an appendix to The Prose Works of William Wordsworth, vol. 2 (1974), aiming to illuminate the origins of the Guide to the Lakes. Unfortunately, Prose Works is out of print, expensive to purchase on the used market, and available mainly in research libraries. It remains an essential source for scholars aiming to trace textual variants; however, it is neither easily obtained nor especially friendly for the general reader, and it places Dorothy Wordsworth in a secondary role.

“Excursion up Scawfell Pike” was occasionally mentioned in scholarship of the 1980s and 90s; for instance, Susan M. Levin discussed it in her Dorothy Wordsworth and Romanticism (1987). Surprisingly, however, Levin chose to omit it from her own anthology, Dorothy Wordsworth, A Longman Cultural Edition (2009). Susan Wolfson chose in 1999 to include most of Dorothy’s “Excursion” in The Longman Anthology of British Literature, making the text available to student readers for the first time.

A few respected critics have discussed the text more recently. Still, it seems safe to say that the text remains an underappreciated part of Dorothy’s oeuvre. We trust that this digital edition makes “Excursion up Scawfell Pike” available to a broader audience while also providing a vital and up-to-date resource to scholars.