Editor’s note: This illustrated, annotated reading text aims to bring Dorothy’s narrative to life in its biographical, historical, and geographical contexts. The text is based on the “Coleorton Manuscript,” a copy Dorothy is presumed to have made for Lady Margaret Beaumont. Important variants from the other surviving manuscript (relatively few) are supplied in the notes, and accurate dates are provided for Dorothy’s undated or misdated entries. See the section introduction for more on the two manuscripts.

[Page 1]

a mountainous ramble

by D Wordsworth

sister to the poet

November 1805

[Day 1; Wednesday, November 6]

William and Mary returned from Parkhouse by the Patterdale road along with Mr. and Mrs. Clarkson, having made a delightful excursion of three days.

They had engaged that William and I should go to Mr. Luff’s on Wednesday or Thursday if the weather continued favorable.

It was not very promising on Wednesday; but, having been fine for so long a time, we thought that there would not be an entire change all at once, therefore on a damp and gloomy morning we set forward, William on foot, and I upon the pony

with William’s great coat slung over the saddle crutch and a wallet containing our bundle of “needments.”

As we went along the mists gathered upon the vallies, and it even rained all the way to the head of Patterdale; but there was never a drop upon my habit larger than the smallest pearls upon a Lady’s ring. The trees of the larger Island upon Rydale Lake were of the most gorgeous colours, the whole Island reflected in the water, as I remember once in particular to have seen it with dear [Page 2] Coleridge,

when either he or William observed that the rocky shore spotted and streaked with purplish brown heath and its image in the water together were like an immense catterpillar, such as when we were children we used to call Woolly Boys,

from their hairy coats. I had been a little cowardly when we left home, fearing that heavy rains might detain us at Patterdale; but as the mists thickened our enjoyments encreased, and my hopes grew bolder; and when we were at the top of Kirkstone

(though we could not see fifty yards before us) we were as happy Travellers as ever paced side by side on a holiday ramble. At such a time and in such a place every scattered stone the size of one’s head becomes a companion: there is a fragment of an old wall at the top of Kirkstone, which, magnified yet obscured as it was by the mist, was scarcely less interesting to us when we cast our eyes upon it than the view of a noble monument of ancient grandeur has been – yet this same pile of stones we had never before observed. When we had descended considerably the fields of Hartsop below Brotherswater were first seen, like a Lake coloured by the reflection of yellow clouds, I [Page 3] mistook them for the water; but soon after we saw the Lake itself gleaming faintly with a grey steelly brightness; then appeared the brown oaks, and the birches of splendid colour, and, when we came still nearer to the valley, the cottages under their tufts of trees and the old Hall of Hartsop with its long irregular front and elegant chimneys.

We had eaten our dinner under the shelter of a Sheep-fold by the bridge at the foot of the mountain, having tethered the pony at the entrance, where it stood without one impatient beating of a foot. I could not but love it for its meekness, and indeed I thought we were selfish to enjoy our meal so heartily while his poor jaws were tethered by the curb bridle. We reached Mr. Luff’s about two hours before tea-time.

Thursday Nov 8th [Day 2; November 7]

Incessant rain till eleven o’clock, when it became fair, and William and I walked to Blowick. Luff joined us by the way. The wind was strong and drove the clouds forward along the side of the hill above our heads; four or five goats were bounding among the rocks; the sheep moved about more quietly or cowered in their sheltering places – the two storm-stiffened [Page 4] black Yew Trees on the crag above Luff’s house were striking objects, close under or seen through the flying mists. I do not know what to say of Blowick; for to attempt to describe the place would be absurd when you for whom I write have been there, or may go thither as soon as you like.

When we stood upon the naked Crag upon the Common, overlooking its woods & bush-besprinkled fields,

the Lake, Clouds, and Mists were all in motion to the sound of sweeping winds – the Church and Cottages of Patterdale scarcely visible from the brightness of the thin mist. Looking backwards toward the Foot of the Water the scene less visionary. Place Fell steady and bold as a lion – the whole Lake driving down like a great river – waves dancing round the small Islands. We walked to the house; the Owner was salving

sheep in the barn – an appearance of poverty and decay every where; he asked us if we wanted to purchase the estate. We could not but stop frequently both in going and returning to look at the exquisite beauty of the woods opposite.

The general colour of the trees was dark brown, rather that of ripe hazel nuts; but towards [Page 5] the water there were yet beds of green, and, in some of the hollow places in the highest part of the woods, the trees were of a yellow colour, and, through the glittering light, they looked like masses of clouds, as you see them gathered together in the West, and tinged with the golden light of the sun. After dinner we walked with Mrs. Luff up the Vale; I had never had an idea of the extent and width of it in passing thro’ along the road on the other side. We walked along the Path which leads from house to house; two or three times it took us through some of those copses or groves that cover every little hillock in the middle of the lower part of the Vale, making an intricate and beautiful intermixture of lawn and woodland. We left William to prolong his walk, and when he came into the house he told us that he had pitched upon the spot where he should like to build a house better than in any other he had ever yet seen.

Mrs. Luff went with him by moonlight to view it. The Vale looked as if it were filled with white light when the moon had climbed up to the middle of the sky; but long before we could see her face, while all the eastern hills were in black shade, those on the opposite side were almost as bright as snow. Mrs. Luff’s large white Dog lay in the moonshine upon the round knoll under the old yew tree, a beautiful and romantic image – the dark [Page 6] Tree with its dark shadow, and the elegant creature as fair as a Spirit.

Friday Nov 9th [Day 3; November 8]

It rained till near ten o’clock; but a little after that time, it being likely for a tolerably fine day, we packed up bread and cold meat, and with Luff’s servant to help to row, set forward in the Boat. As we proceeded the day grew finer – clouds and sunny gleams on the mountains. In a grand Bay under Place Fell we saw three Fishermen with a Boat dragging a net, and rowed up to them. They had just brought the net ashore, and hundreds of fish were leaping in their prison. They were all of one kind, what are called Skellies.

After we had left them the Fishermen continued their work, a picturesque group under the lofty and bare crags; the whole scene was very grand; a raven croaking on the mountain above our heads.

– Landed at Sanwick [Sandwick]– the man took the Boat home, and we pursued our journey towards the village along a beautiful summer path, at first through a copse by the Lake side, then through green fields – The Village and Brook very pretty, shut out from mountains and Lakes – it reminded me of Somersetshire

– Passed by Harry Hebson’s house – I longed to go in for the sake of former times. William went up one side [Page 7] of the Vale, and we the other, and he joined us after having crossed the one-arched bridge above the Church – a beautiful view of the church with its “bare ring of mossy wall” and single Yew Tree.

At the last house in the Vale we were kindly greeted by the Master, who was sitting at the door salving sheep – he invited us to go in and see a room lately built by Mr. Hazel

for his accommodation at the yearly chace of red Deer in his Forests at the head of these Dales; the room is fitted up in the sportsman’s style, with a single cupboard for bottles and glasses &c. some strong chairs, and a large dining table; and ornamented with the horns of the stags caught at these Hunts for many years back, with the length of the last race they ran recorded under each. We ate our dinner here; the good woman treated us with excellent butter and new oat bread, and, after drinking some of Mr. Hazel’s strong Ale we were well prepared to face the mountain, which we began to climb almost immediately. Martindale divides itself into two dales at the head. In one of these (that to the left) there is no house to be seen, nor any building but a cattle shed on the side of a hill which is sprinkled over with wood, evidently the remains of a Forest, formerly a very extensive one. At the bottom of the other Valley is the house of which I have spoken, and beyond the enclosures of this man’s [Page 8] Farm there are no other – A few old trees remain, relicks of the Forest, a little stream passes in serpentine windings through the uncultivated valley, where many Cattle were feeding – the Cattle of this country are generally white or light-coloured; but those were mostly dark brown or black, which made the scene resemble many parts of Scotland.

When we sate on the hillside, though we were well contented with the quiet every-day sounds, the lowing of cattle, bleating of sheep, and the very gentle murmuring of the valley stream, yet we could not but think what a grand effect the sound of the Bugle Horn would have among these mountains. It is still heard once a year at the Chace I have spoken of, a day of festivity for all the Inhabitants of this District except the poor Deer, the most ancient of them all. The ascent, even to the top of the mountain, is very easy.

When we had accomplished it we had some exceedingly fine mountain views, some of the mountains being resplendent with sunshine, others partly hidden by clouds. Ulswater was of a dazzling brightness bordered by black hills – the Plain beyond Penrith smooth and bright, (or rather gleamy) as the sea or sea Sands. Looked into Boar Dale above Sanwick, deep and bare, a stream winding down it. After having walked a considerable way on the tops of the hills, came in view of Glenriddin and the [Page 9] mountains above Grisdale. Luff then took us aside, before we had begun to descend, to a small Ruin which was formerly a Chapel or place of worship where the Inhabitants of Martindale and Patterdale were accustomed to meet on Sabbath days.

There are now no traces by which you could discover that the Building had been different from a common sheep-fold; the loose stones, and the few which yet remain piled up are the same as those which lie about on the mountain; but the shape of the building, being oblong, is not that of a common sheep-fold, and it stands East and West. Whether it was ever consecrated ground or not I know not; but the place may be kept holy in the memory of some now living in Patterdale; for it was the means of preserving the life of a poor old man last summer who, having gone up the mountain to gather peats, had been overtaken by a storm, and could not find his way down again. He happened to be near the remains of the old Chapel, and, in a corner of it, he contrived, by laying turf and ling

and stones from one wall to the other, to make a shelter from the wind, and there he lay all night. The Woman who had sent him on his errand began to grow uneasy towards [Page 10] night and the neighbours went out to seek him. At that time the old Man had housed himself in his nest, and he heard the voices of the men; but could not make them hear, the wind being so loud, and he was afraid to leave the spot least he should not be able to find it again, so he remained there all night, and they returned to their homes giving him up for lost; but the next morning the same persons discovered him huddled up in the sheltered nook. He was, at first, stupefied and unable to move; but after he had eaten and drunk, and recollected himself a little, he walked down the mountain, and did not afterwards seem to have suffered.

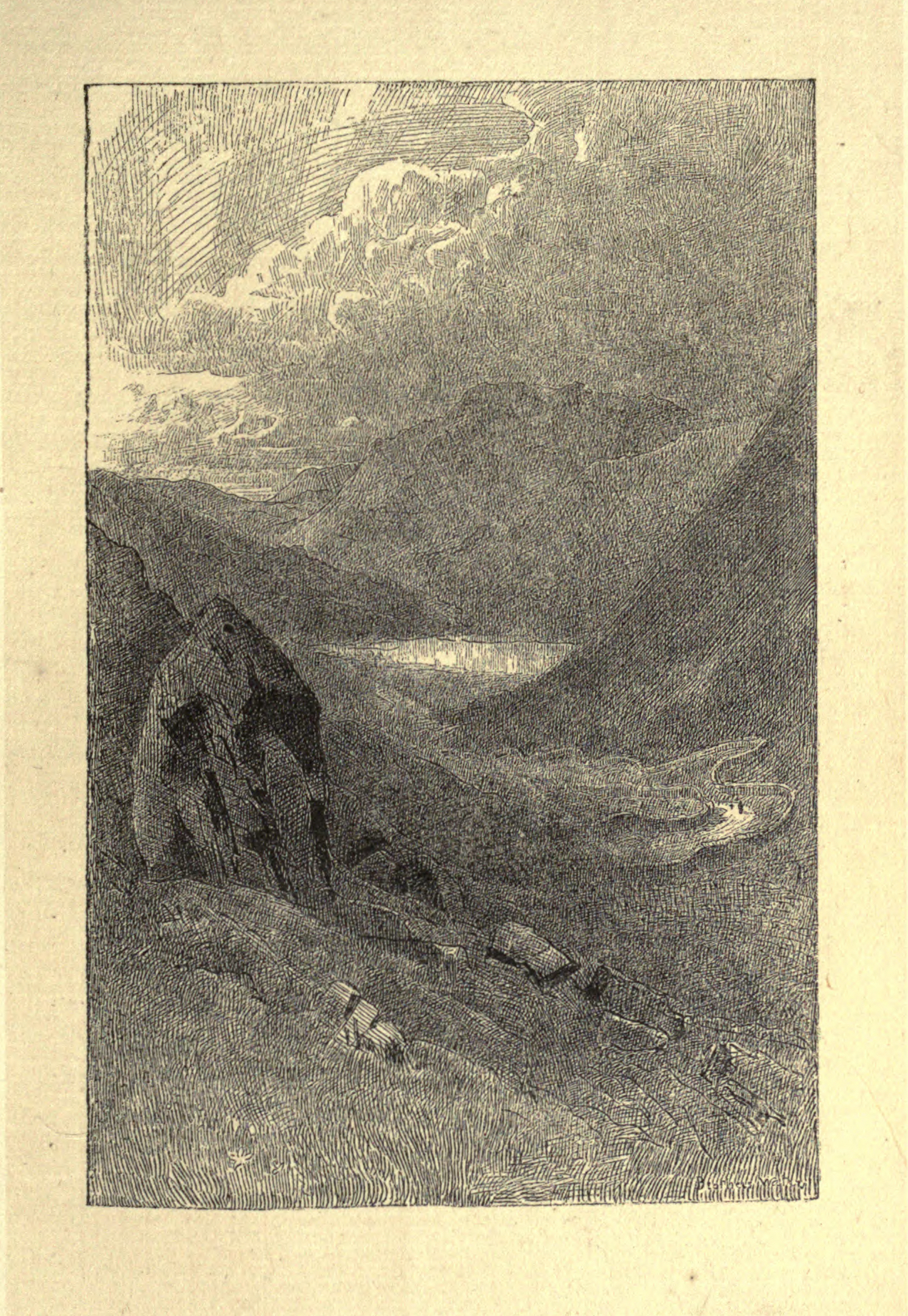

As we descend, the Vale of Patterdale appears very simple and grand with its two heads, Deep-dale, and Brotherswater or Hartsop. It is remarkable that two pairs of Brothers should have been drowned in that Lake. There is a tradition, at least, that it took its name from two who were drowned there many years ago, and it is a fact that two others did meet that melancholy fate about twenty years since. It was upon a New-year’s Day. Their Mother had sent them to thresh some corn, and they, probably thinking it hard to be so tasked when all others were keeping holiday, stole out to slide upon the ice and were both drowned. A Neighbour [Page 11] who had seen them fall through the ice, though not near enough to be certain, guessed who they were, and went to the mother to inquire after her sons. She replied that they were in the Barn threshing, “Nay,” said the Man, [“]they are not there, I am sure, and it is not likely today.” The Woman went with him to the Barn and the Boys were gone: he was then confirmed, and told her that he believed that they were drowned. It is said that they were found locked in each other’s arms. I was exceedingly tired when we reached home, owing to the steepness and roughness of the peat track by which we descended. I lay down on the Sofa in Mrs. Luff’s parlour and was asleep in three minutes———. A fine moonlight night – a thick fog in the middle of the Vale, which disheartened William about the situation of his house. Supped on some of the Fish caught by the Fishermen at the foot of Place Fell. We thought them excellent.

Saturday Nov 10th [Day 4; November 9]

A beautiful morning. When we were at breakfast we heard suddenly the tidings of Lord Nelson’s death, and the Victory of Trafalgar.

Went to the Inn to make further inquiries

– I was shocked to hear that there had been great [Page 12] rejoicings at Penrith. Returned by William’s rock and grove, and were so much pleased with the spot that William determined to buy it if possible, therefore we prepared to set off to Park House that William might apply to Thomas Wilkinson

to negotiate for him with the owner. We went down that side of the Lake opposite to Stybarrow Crag. I dismounted, and we sate some time under the same rock as before, above Blowick. Owing to the brightness of the sunshine the Church and other buildings were even more concealed from us than by the mists the other day. It had been a sharp frost in the night, and the grass and trees were yet wet. We observed the lemon-coloured leaves of the birches in the wood below, as the wind turned them to the sun, sparkle, or rather flash, like diamonds. The day continued unclouded to the end. We had a delightful ride and walk, for it was both to both of us. We led the horse under Place Fell, &, though I mostly rode when the way was good, William sometimes mounted to rest himself. Called at Eusemere

– Went by Bower Bank, intending to ford the Emont at the Mill; but the pony would not carry us both, so, after many attempts, I rode over myself and a Girl followed me on another horse to take back the pony to William. Very cold [Page 13] before we reached Park House. Derwent

ran to meet us. Sate in the kitchen till the parlour fire was lighted, and then enjoyed a comfortable dish of tea. After tea William went to Thomas Wilkinson’s and to Brougham.

Monday, November 12th [Day 6, November 11]

The morning being fine, we resolved to go to Lowther,

and accordingly Sara Hutchinson

mounted her Brother’s horse, I the pony, and William and Miss Green set out on foot; but she had not walked long before she took a seat behind Sara. Crossed the Ford at Yanworth ——— Found Thomas Wilkinson at work in one of his fields; he chearfully laid down the spade and walked by our side with William. We left our horses at the Mill below Brougham, and walked through the woods till we came to the Quarry, where the road ends, the very place which has been the Boundary of some of the happiest of the walks of my youth. The sun did not shine when we were there; and it was mid-day, therefore if it had shone, the light could not have been the same; yet so vividly did I call to mind those walks that when I was in the wood I almost seemed to see the same rich light of evening upon the trees which I had seen in those happy hours. My heart [Page 14] was full; and I could not but grieve that any strangers were with us.

At this time the Path was scarcely traceable by the eye, all the ground being covered with withered leaves, which I was very sorry for, William having spoken of the beauty of it with so much delight after he had been at Lowther in the summer. Scrambled along under the Quarry; then came to Thomas Wilkinson’s new path. We spent three delightful hours by the River side and in the woods. Called at Richard Bowman’s.

We had a pleasant ride home; Sara and I stopped at Red Hills while William went over the Ford to Thomas Wilkinson’s. The House untidy and uncomfortable – a little Girl never ceased rocking the Baby in the cradle. We asked if it would not sleep without rocking, and the Mother said “No, for she was used to it” – Reached Park House at ten o’clock – Joanna

had waited dinner and tea for us.

Tuesday, November 13th[Day 7, November 12]

A very wet morning – no hope of being able to return home. William read in a Book lent him by Thomas Wilkinson. I read Castle Rackrent.

The day cleared at one o’clock and after dinner, at a little before three we set forward. The pony was bogged in Tom’s field, & I was obliged to dismount – Went over Soulby Fell. Before we reached Ulswater the [Page 15] sun shone, and only a few scattered clouds remained on the hills except at the tops of the very highest – the Lake perfectly calm – We had a delightful journey. At the beginning of the first Park William got upon the pony, and, betwixt a walk and a run, I kept pace with him while he trotted to the next gate; then I mounted again. We were joined by two Travellers; like ourselves, with one white horse between them. We went on in company till we came near to Patterdale, trotting most of the time. The Trees in Gowborough Park were very beautiful, the hawthorns leafless – their round heads covered with rich red berries, and adorned with arches of green brambles, and eglantine hung with glossy hips – Many birches yet tricked out in full foliage of bright yellow – Oaks brown or leafless – the smooth branches of the ashes bare – most of the alders green as in spring. I think I have more pleasure in looking at deer than any other animals, perhaps chiefly from their living in a more natural state. At the end of Gowborough Park, a large Troop of them were moving slowly, or standing still, among the fern. I was grieved when our companions startled them with a whistle, disturbing a beautiful image of grave simplicity and thoughtful enjoyment; for I could have fancied that even they were partaking with me a sensation of the solemnity of the closing day. [Page 16] The sun had been set some time, though we could only just perceive that the daylight was partly gone, and the Lake was more brilliant than before. I dismounted again at Stybarrow Crag,

and William rode till we came almost to Glenriddin. Found the Luffs at tea in the kitchen. After tea set out again; Luff accompanied me on foot and William continued to ride till we came to the foot of Brothers-water. – A delightful evening – the Seven Stars close to the hill tops in Patterdale – all the stars seemed brighter than usual. The steeps were reflected in Brothers-water, and above the Lake appeared like enormous black perpendicular walls. The torrents of Kirkstone had been swoln by the rains, and filled the mountain Pass with their roaring, which added greatly to the solemnity of our walk – the stars in succession took their stations on the mountain tops. Behind us, when we had climbed very high we saw one light in the Vale at a great distance, like a large star, a solitary one, in the gloomy region – all the cheerfulness of the scene was in the sky above us. Found Mary & the children in bed – no fire – luckily William was warm with walking, and I not cold, having wrapped myself up most carefully, & the night being mild.