On Christmas Day of 2021, admirers of Dorothy Wordsworth (1771–1855) around the world celebrated the sestercentennial of a writer who, after long years in her elder brother’s shadow, has at last gained an independent reputation. Dorothy (fig. 1) is now widely known as one of nineteenth-century England’s most perspicacious nature writers and keen-eyed chroniclers of the everyday. There has never been a better time to study her life and work, as besides an ever-growing body of biographical and critical studies, recent decades have seen the arrival of several important print collections of her writings, including the first-ever classroom anthology of her “greatest hits” as a diarist, travel writer, and poet.

And, thanks to Google Books and other digital libraries, anyone with an internet connection can now freely access scans of the late Victorian editions that first introduced Dorothy’s (nearly) complete works to a broad readership.

Figure 1. Silhouette of Dorothy Wordsworth, ca. 1806, one of only three known likenesses of her (Courtesy: Wordsworth Trust)

Even in the wake of such advances, Dorothy Wordsworth’s Lake District represents a major step forward for both the general availability and scholarly study of her remarkable journals, poems, and travel writings. While more a topical anthology than complete works edition, this Romantic Circles Electronic Edition offers by far the most extensively annotated and meticulously transcribed collection of Dorothy’s texts to date. Its central thematic focus is the deep connection, at once aesthetic, affective, and spiritual, that this most observant of writers felt with the people and scenery of her native Lake District. Yet, even while concentrated on a single region, this edition might also be taken as a general introduction to Dorothy’s writings, as it samples widely from her output in a range of genres and across all phases of her adult life, featuring both well-known works like her Grasmere journal notebooks and others that have either never before been published or never appeared in a reliable edition. Several texts, moreover, appear in multiple versions, and all are introduced with critical essays and headnotes explaining their composition, reception, and biographical and historical contexts.

To cater to specialized scholars and general readers alike, we have divided our prefatory material into two parts. This introduction reviews the pertinent aspects of Dorothy’s life, our rationale for focusing on her Lakeland writings, and the edition’s contents. A separate essay on our “Editorial Philosophy and Guidelines” situates this project within the history of editing women writers in general and Dorothy Wordsworth in particular, articulates the advantages of publishing such an edition in an open-access digital format, and summarizes our editorial practices and principles of selection.

A Life in the Lakes

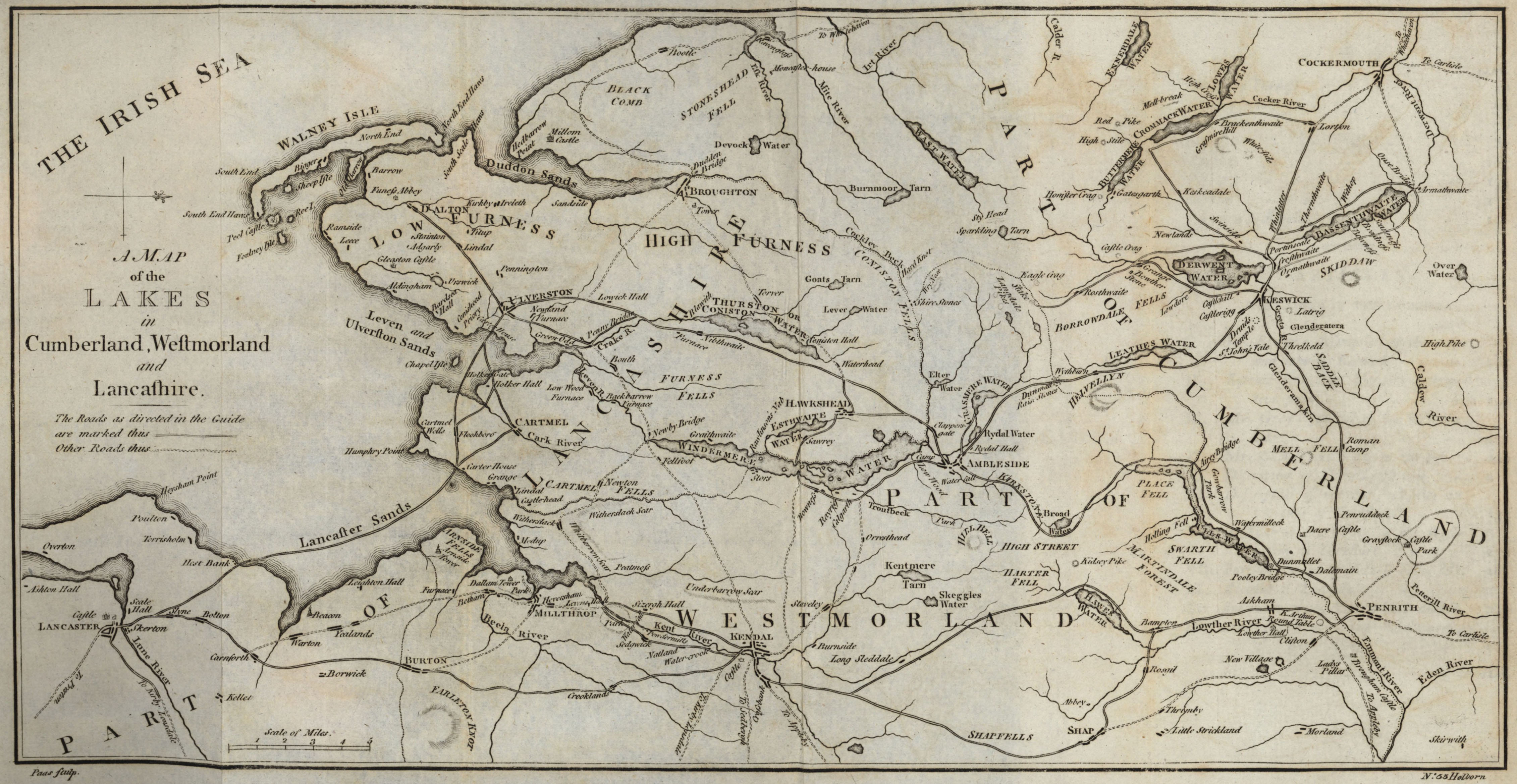

The third of John and Ann Wordsworth’s five eventual children, and their only daughter, Dorothy Wordsworth was born on 25 December 1771 in Cockermouth, Cumberland, a town in the northwest corner of the English Lake District (fig. 2). After six happy years with her parents and brothers, she suddenly found her comfortable childhood upended by her mother’s passing in early 1778. While her brothers would remain in the Lakes, staying with relatives when not attending Hawkshead Grammar School, Dorothy would largely be exiled from the region for over two decades, spending most of her formative years with relatives in Halifax, Yorkshire (1778–1787) and Forncett, Norfolk (1788–1794). An 18-month stay with her maternal grandparents in Penrith in 1787–1788 did little to ease her sense of displacement, though it did rekindle her love for the region’s beauty and yield lifelong friendships, especially with her future sister-in-law, Mary Hutchinson.

Figure 2. Pullout Map of the Lakes (with north on the right and west on the top) from Thomas West’s A Guide to the Lakes, in Cumberland, Westmorland, and Lancashire, 5th ed. (London: W. Richardson, 1793). Cockermouth is in the upper right corner and Ambleside, Rydal Water, and Grasmere are slightly right of center.

For good reason, then, virtually every biographer has stressed the joy and relief Dorothy felt in her mid-to-late 20s upon reconnecting with her siblings and returning to her native Cumbria. What is generally considered the happiest period of her life began in 1795, when she and William, the brother 20 months her senior to whom she had always felt especially close, were finally able to live under the same roof. Four years later, after sojourns in the south of England and in Germany, they and their younger brother John began planning to establish a permanent home in the Lakes. While touring the Lake District with Samuel Taylor Coleridge in November 1799, William reported to Dorothy that “C[oleridge] was much struck with Grasmere and its neighbourhood and I have much to say to you[;] you will think my plan a mad one, but I have thought of building a house there by the Lake side. John would give me £40 to buy the ground, and for £250 I am sure I could build one as good as we can wish.”

This vision clearly outpaced their finances, as William and Dorothy were tight on funds and John was just launching his career as a merchant sailor. Nevertheless, the siblings were so taken with the prospect of making a home together in Grasmere that by the year’s end William and Dorothy had taken a lease on the home now known as Dove Cottage and John had promised to join them on his next shore leave.

Lucy Newlyn recently observed that, “returning to the Lake District to reclaim their regional identity and reestablish their family, the Wordsworths found themselves at one remove from their childhood origins—neither insiders nor quite outsiders in Grasmere.”

Yet any such dual consciousness was likely felt more acutely by Dorothy than her brothers, as, unlike them, she had not spent her formative years attending school just south of Grasmere in Hawkshead. Accordingly, her distinctive position as an insider-outsider in the Central Lakes frequently shows through in earlier selections in this edition (especially the first journal notebook), which display a deep curiosity about the area’s society, topography, and plant and animal species and speak in the voice of one making the transition from tourist to longtime resident.

While William and Dorothy would never build the dream house they began imagining in 1799, their other wish, to establish a permanent home in the area, was fulfilled entirely. Dove Cottage served as their cramped but cherished abode from December 1799 through May 1808, a period when the siblings composed many of their most iconic works and were joined first by Mary Hutchinson, whom William married in October 1802, and then by the couple’s first three children. Famously, these were years of “plain living and high thinking,”

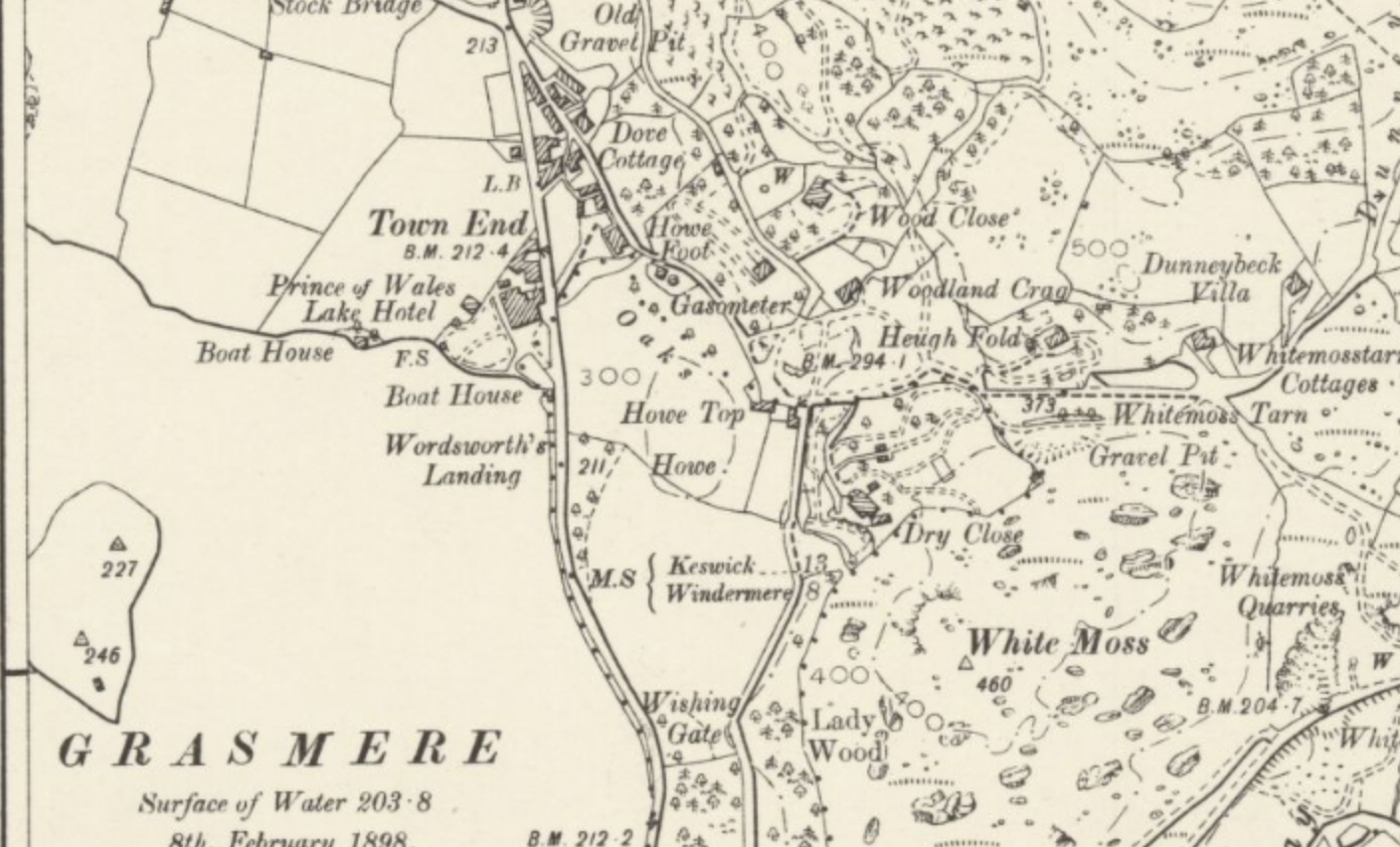

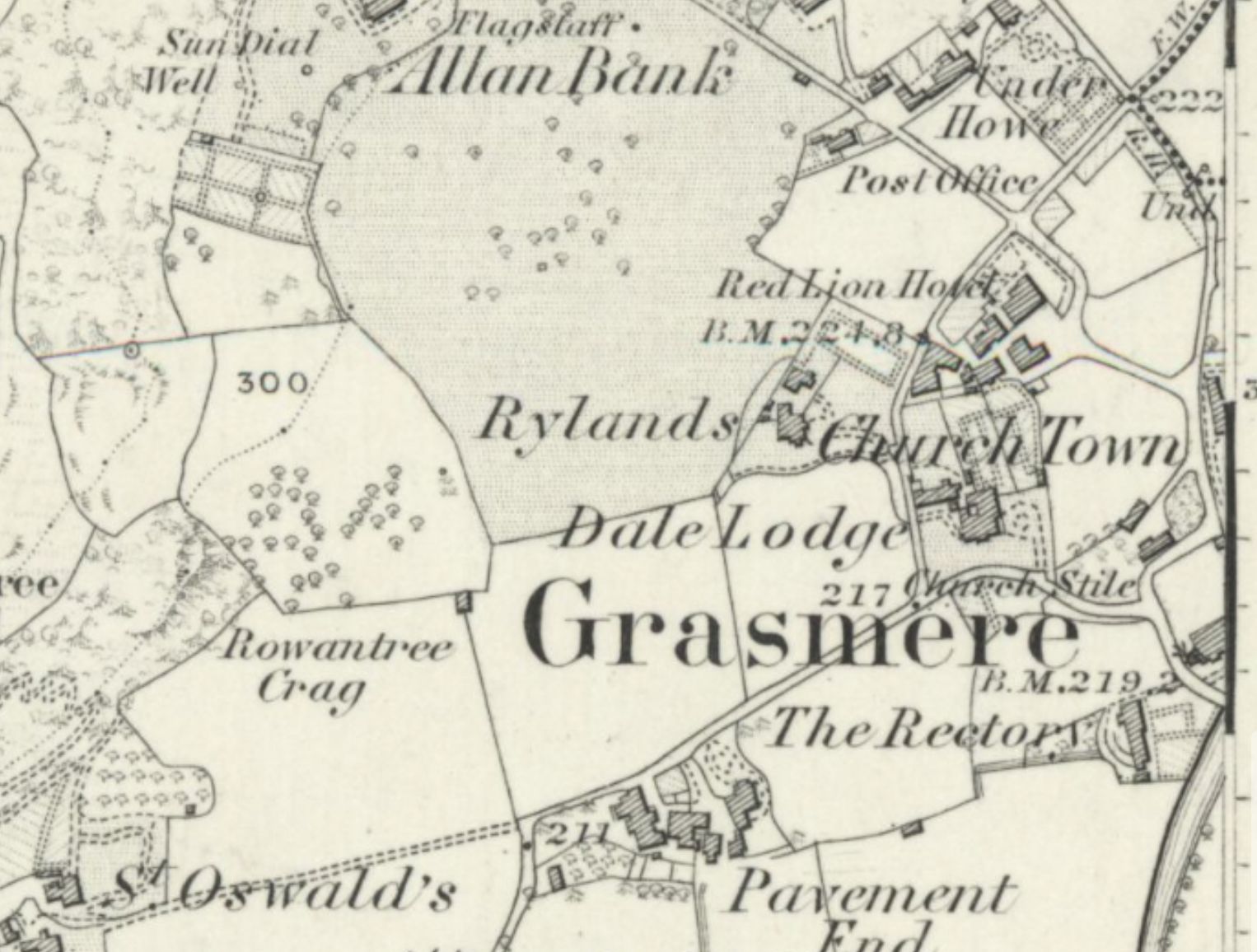

blending domestic work, literary collaboration, and outdoor pursuits. Having outgrown Dove Cottage, the family spent three years at Allan Bank in Grasmere, where William and Mary’s two youngest children were born, followed by two years in the village rectory (figures 3–4). Then, in May 1813, after William secured a government post that significantly eased the family’s money worries, they moved two miles east of Grasmere to Rydal Mount, the spacious and comfortable home in which William, Mary, and Dorothy would reside until their respective deaths in the 1850s.

Figure 3. View of Grasmere from the 1897 Ordinance Survey of England and Wales, showing the Wordsworths’ three homes: Dove Cottage (top center of Fig. 3), Allan Bank (top center of Fig. 4), and The Rectory (bottom right of Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Allan Bank and the Rectory

The Wordsworths’ Grasmere period is rightly celebrated in the annals of British literature. But if, as traditional accounts suggest, William’s peak years as a poet were behind him by 1813, the family’s first two decades at Rydal Mount saw Dorothy reach new heights both in her literary creativity and output. There she composed most of her poems and reworked for potential publication journals she kept on the Continent in 1820 and in Scotland in 1822. At Rydal she also returned to keeping a daily journal, ultimately filling 15 notebooks, known collectively as the Rydal Journals, between 1824 and 1835. Two of these notebooks, the first and last, appear in their entirety for the first time in this edition.

Into her late fifties, Dorothy remained remarkably vigorous both in mind and body, frequently remarking that she felt even more energetic than in her twenties. But, as chronicled in the latter half of the Rydal Journals, her health gradually but irreparably declined after she became severely ill in early 1829. By the end of 1835 chronic pain, a lack of stamina, and intermittent dementia effectively ended her writing career, and she would spend her final two decades confined to the house and grounds of Rydal Mount. After her passing on 25 January 1855, she was buried in the Grasmere churchyard alongside her brother William and numerous beloved friends and family members.

Imagining “Dorothy Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes”

Considering that in his later years William was widely seen as England’s greatest living bard and that he would eventually replace Byron as the face of British Romanticism, it was perhaps inevitable that his sister’s life and works would first be valued primarily for whatever insights they afforded into his writings. And, while just how willingly Dorothy played the handmaiden to William’s genius remains hotly contested, her letters and journals suggest she would have had few qualms about going down in literary history as her brother’s unwavering assistant and occasional collaborator.

Moreover, it is abundantly clear from the trove of unpublished journals, travelogues, stories, poems, and commonplace books she left behind that she wrote primarily for herself or close family and friends.

At the same time, as this collection repeatedly demonstrates, many of Dorothy’s literary efforts had a more public-facing and professional intent than has generally been acknowledged. Her longtime friend Thomas De Quincey, for one, attested to both her distinctive genius and bona fides as public author when he maintained in 1839, “Miss Wordsworth would have merited a separate notice in any biographical dictionary of our times, had there even been no William Wordsworth in existence.”

Seconding De Quincey’s assessment, this edition shines the spotlight solely on Dorothy, showcasing her gifts in a variety of literary forms and her distinctive perspectives on the people and places of the English Lakes.

The initial spark for this project can be traced to an earlier Romantic Circles collaboration, the scholarly edition of William Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes that Nicholas Mason and Paul Westover, in collaboration with students and colleagues at Brigham Young University (BYU), published in 2015 and revised and expanded in 2020. While investigating the textual history of the five distinct editions of William’s Guide, we were routinely struck by his sister’s crucial, if largely unacknowledged, contributions. This led us to ponder what a “Guide to the Lakes” written entirely by Dorothy might look like, a question we soon took up with Michelle Levy of Simon Fraser University (SFU), a fellow Romanticist who had worked extensively with Dorothy’s manuscripts in researching her articles and books on women’s writing, manuscript culture, and family authorship.

As we three began seriously considering how we might reverse engineer such a “guidebook” from Dorothy’s writings on the Lakes, we turned to Jeff Cowton, the longtime curator at the Wordsworth Trust, and several BYU and SFU students who had worked with the Wordsworths’ manuscripts while interning or studying in Grasmere. The result has been a collaborative process of over seven years, in which the three lead editors have worked with the Wordsworth Trust and student researchers to study, transcribe, and contextualize Dorothy’s works. Although, in their final forms, the critical apparatus and texts to follow were primarily authored or edited by an experienced scholar—with Michelle Levy leading out on the Grasmere Journal excerpts, the Greens narrative, and the poems; Paul Westover on the Ullswater and Scafell Pike excursions; and Nicholas Mason on the Rydal Journals—every part of this edition has been deeply collaborative.

In the early stages of this project, we informally called it “Dorothy Wordsworth’s Guide to the Lakes.” But, not wanting to confuse readers or perpetuate the image of Dorothy invariably following in her older brother’s footsteps, we eventually settled on the less allusive “Dorothy Wordsworth’s Lake District.” Whatever its liabilities, however, our working title still encapsulates our vision of gathering and showcasing Dorothy’s vivid portraits of this famously picturesque region, which ultimately became Lake District National Park (1951) and a UNESCO World Heritage Site (2017). Strictly speaking, apart from the substantial sections she supplied for William’s Guide, Dorothy never composed guidebook material as such.

In fact, in an amusing 1803 letter to her friend Catherine Clarkson, she ranted, “I think journals of Tours except as far as one is interested in the travellers are very uninteresting. Wretched, wretched writing!”

It’s all the more ironic, then, that travel writing—along with the notes, letters, and diary entries inspired by walks closer to home—would become central to her creative output and legacy. Works based on her experiences as a traveler or short-term resident include her journals from Alfoxden and Germany (both 1798), her Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland (1803–1806), her Journal of a Tour on the Continent (1820), her second tour of Scotland (1822), and large segments of the Rydal Journals written on the road. While these texts encompass various literary traditions—nature diary, weather journal, travelogue, commonplace book, and so forth—they cohere as records of things observed and felt by a writer who, left to her own devices, would often walk over a dozen miles a day. Even when at home in Cumbria and drawing on daily experience, Dorothy might say, as Thoreau would years later, that she had “traveled a good deal” in the Lake District.

Tellingly, we are not the first to note that both William and Dorothy serve as “guides” to the Lakes. Eric Sutherland Robertson, for instance, asked in his 1911 book Wordsworthshire, “Who wrote the noblest Guide to the Lakes—William or Dorothy? Let the reader study every page of the [Grasmere] Journal and of the other work before attempting to decide.”

As Robertson implies, while the brother’s poetry has undoubtedly shaped our perceptions of the Lake District, it has become equally impossible for the well-read traveler to imagine “Wordsworth Country” without considering Dorothy’s writing.

Edition’s Contents

Our edition aims to bolster Dorothy’s growing reputation as one of the great chroniclers of this, or any, British region’s history and geography, people and customs, and flora and fauna. Accordingly, when selecting its contents, we typically excluded works that are set in or focused upon areas outside the Lakes (for instance, her tours of Scotland and the Continent and several sections of her Rydal Journals). Even then, however, there were more than enough texts to choose from for an edition of this scope, which forced us to leave several brilliant descriptions of the region on the cutting-room floor. Dorothy’s letters alone, for instance, with their recurring effusions on the joys of rambling throughout Westmorland fells and dales, could easily supply enough content for a substantial anthology of Lakeland writing.

Each section of this edition features a separate critical and editorial introduction and extensive illustrations and contextual materials, including manuscript facsimiles, maps, photographs, and biographical indices. Together, these resources offer a rich, multimodal vision of Dorothy Wordsworth’s writing life and the Lake District home she loved. The texts we ultimately selected can be grouped as follows:

1. The first Grasmere journal notebook (1800, DCMS 20).

While Dorothy’s entries from her early years at Dove Cottage are already the most familiar of her writings, the first of her four Grasmere journal notebooks is reintroduced here in an unfamiliar format. Specifically, we offer a diplomatic transcription of this first notebook, presenting it in its raw manuscript form to highlight both its material context and the complexity of Dorothy’s writing practices. This notebook covers the seven months between 14 May and 22 December 1800, offering an intimate portrait of Westmorland life at the moment when the Wordsworths returned to the area for good. It also captures Dorothy’s love for walking, all but inviting us along on her daily rambles through the Lakes.

2. “A Narrative Concerning George & Sarah Green, of the Parish of Grasmere, addressed to a Friend” (1808, DCMS 64).

In this moving account, written to raise money for children orphaned by a tragic accident, Dorothy offers a chapter of local history. Widely circulated in manuscript, her chronicle of poverty, grief, and community relief efforts highlights the informal social contract binding together people of all classes in the valleys of the Central Lakes. This public-facing text also complicates our understanding of Dorothy’s motives for writing, conceptions of audience, and views about publication.

3. “Excursion on the Banks of Ullswater” (1805) and “Excursion up Scawfell Pike” (1818).

Abridged versions of Dorothy’s accounts of excursions she made with friends to different parts of the Lake District were among her earliest published writings, appearing (albeit without acknowledgment of her authorship) in the 1822 and 1823 editions of her brother’s Guide to the Lakes. Showcasing Dorothy’s gifts for nature writing and her indefatigability as a Lakeland fell-walker and mountaineer, these important texts represent Dorothy’s most direct contributions to Lake District travel literature. While long available in print, they have never before been annotated, illustrated, or contextualized as thoroughly as they are here. This edition also details the accounts’ complex textual histories and brings Dorothy’s adventures to life with a pair of interactive maps.

4. Poems from the Commonplace Book (1805–1835?, DCMS 120).

Though Dorothy was self-effacing about her poetic abilities, verse became an important genre for her, especially in later years. This is evidenced by what the Wordsworth Trust labels her Commonplace Book (DCMS 120), which, along with miscellaneous extracts and quotations, includes copies of most of her known poems. Many of these poems, moreover, appear in multiple versions, thereby displaying how serious she was about reworking and recopying them. Besides offering a diplomatic transcription of all of the verse in DCMS 120, whether complete poems or fragments, this section also includes an introductory essay on what we can learn from Dorothy’s poetry manuscripts and multiple “Tables of Contents” modelling different sequences in which the poems might be studied.

5. Notebooks 1 and 15 of the Rydal Journals (1824–1825, 1834–1835, DCMS 104.1 and 118.5).

Despite the renown of Dorothy’s earlier journals, most of the 15 notebooks recording her daily life between 1824 and 1835 remain unpublished. This edition’s annotated texts of the first and last volumes of her Rydal Journals therefore represent a watershed of sorts in offering a wealth of new perspectives on Dorothy’s daily life in late middle age. Both notebooks included here reflect an abiding affinity for the scenery and inhabitants of the Lakes; but, whereas Notebook 1 captures a period marked by boundless energy, Notebook 15 finds her confined to a sickbed, reminiscing over past excursions and taking in whatever sights and sounds she can from her upstairs room at Rydal Mount.