I: Contexts for “Ullswater Excursion”

A. Composition and Reception

B. Occasion of Dorothy’s Narrative

II: Textual and Editorial Issues

A. Manuscripts

B. Dorothy’s Account vs. William’s Guide to the Lakes

C. Published Versions

D. Editorial Principles

A. Composition and Reception

On 6 November 1805, just as mild weather gave way to autumn rain, Dorothy and William Wordsworth set out to see their friends Charles and Letitia Luff in Patterdale, 12 miles northeast of Grasmere on the southern tip of Ullswater.

They planned for only a short visit but ended up spending a week exploring what Dorothy called the “wonderful country” around England’s second-largest lake.

Her account of this tour, “Excursion on the Banks of Ullswater” (hereafter “Ullswater Excursion”), presents her observations and experiences in genial prose. Since many of the landmarks she mentions remain today, much of what she saw appears in our interactive map and the photographic illustrations accompanying our annotated reading text.

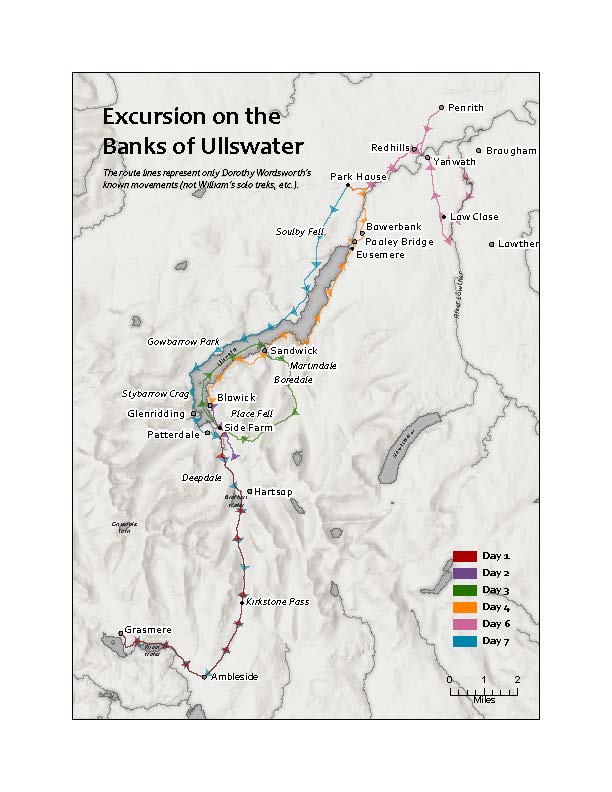

Dorothy’s Ullswater tour was essentially a counterclockwise circuit of the lake punctuated by side excursions. Afterward, she summarized her itinerary for her friend Catherine Clarkson: “William and I spent three days at Luff’s and three at Park house.

We went the Wednesday after you left us—walked with Thomas Wilkinson through the Lowther woods—a marvelously beautiful walk. . . . We rode to Park House under Stybarrow Crag, and the day before we were also in Martindale with the Luffs—crossing over the mountain back to Patterdale.”

If we add that the siblings crossed the Kirkstone Pass (1,489 ft.—the Lake District’s highest road) to reach the Luffs’ and that six days later they marched down Ullswater’s long western shore and traversed Kirkstone again, we can imagine something like the trip’s full circle (see fig. 3.1).

Figure 1. Route of the Ullswater tour—a counterclockwise circuit with side expeditions on days 3 and 6.

“Ullswater Excursion” is among the projects Susan Levin has described as “narratives in which Dorothy Wordsworth represents herself as the woman who goes out to seek experience in the company of family and friends.”

It belongs to the Dove Cottage period, when Dorothy also produced her Grasmere Journals (1800–1803) and Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland, A.D. 1803. In fact, “Ullswater Excursion” was composed at roughly the same time as Recollections,

and, though shorter, it belongs to the same genre, the reconstructed travel journal.

As Ernest de Sélincourt explained, her Scottish journal was “written at leisure after her return, while the events recorded were still vivid in her memory, and when she could see the whole tour in something of artistic perspective”; the same seems to be true of the Ullswater text.

While Dorothy included some details from the trip in a letter she wrote on the trip’s second day, she apparently waited until after her return to Grasmere to draft the full narrative.

Why she wrote this account, and for whom, is not altogether clear. As the Grasmere Journals (1800–1803) demonstrate, personal and shared memories routinely jostled together in her notebooks, and she often recorded experiences as potential sources for her own future writing or for William’s. In “Ullswater Excursion,” she records joyful moments with her brother, yet she clearly has an external audience in mind. She remarks in her report on day 2, “To attempt to describe the place would be absurd when you for whom I write have been there, or may go thither as soon as you like.” Thus, her first intended reader (or readers) must have lived in or near the Lake District or had the means to visit easily. She might have said, as she later did concerning her Scottish tour, “I wrote my journal, or rather recollections for the sake of my Friends who it seemed ought to have been with us, but were confined at home by other duties.”

At this point, seemingly, she had no thoughts of print publication.

In 1941, De Sélincourt speculated that Dorothy wrote “Ullswater Excursion” for Lady Margaret Beaumont, citing William’s 1823 explanation that it “was written for one acquainted with the general features of the country.”

In light of the letters Dorothy sent to Lady Beaumont during and just after the Ullswater tour, she was likely the one of whom William spoke (see section appendix) . Although the two women had yet to meet in person, they had been carrying on a warm correspondence.

Perhaps Lady Beaumont, enthused by Dorothy’s letters, had asked for a longer, more circumstantial account of her adventure. She and her husband, Sir George, were generous patrons as well as friends to the Wordsworths, so Dorothy was understandably eager to please them. “Ullswater Excursion” might, then, be read as a reciprocal gift offered in a spirit of gratitude.

As detailed more fully in Section II, two manuscript versions of “Ullswater Excursion” survive. The first, preserved in one of Dorothy’s notebooks, is slightly longer and somewhat messier, while the second—a fair copy likely prepared for Lady Beaumont—removes some details while offering clarifications and stylistic adjustments. Regrettably, we know little about the manuscripts’ use or possible circulation. Our primary clues about their reception are the simple facts already related: one copy was carefully preserved by the Beaumonts, and the other, retained by Dorothy herself, remained significant in Wordsworth family memory. William thought highly enough of it to make it part of his Lakeland guidebook, and, years later, nephew Christopher mentioned it in his 1851 Memoirs of William Wordsworth, acknowledging the authorship of his aunt.

Dorothy composed “Ullswater Excursion” at a time distinguished by creative accomplishment but also by personal and family worries. She left a good deal unsaid. For instance, when she reports that “Derwent ran to meet us,” informed readers should picture a five-year-old who has not seen his father for almost two years, eager to embrace some of the most important adults in his life. The missing father, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, appears by name at only one point, yet his perplexing absence hangs in the air. Then, to acknowledge another powerful absence, when Dorothy describes coming in view of “the mountains above Grisedale,” ostensibly making the plainest sort of topographical reference, she unavoidably has in mind her beloved brother John—Captain John Wordsworth, who died in a shipwreck in February. It was near Grisedale Tarn that she and William parted with him after his last visit to Grasmere, bidding farewell as he rushed down the Ullswater side of the mountains, full of hope about his coming voyage on the Earl of Abergavenny. It was there, too, that William had found a vent for his feelings in early June, composing an elegy through tears.

As Dorothy exclaimed in her 9 June letter to Lady Beaumont, “Oh! My dear Friend, you will not wonder that we love that place.”

Similarly, when in “Ullswater Excursion” she recounts the tale of two local brothers drowning (thus explaining the name of “Brothers Water”), it seems unimaginable that she isn’t also reflecting on the recent drowning of her own brother. And might she not also think of him when she describes learning about the death of Admiral Nelson at Trafalgar?

Indeed, with all of these interweaving stories in mind, Dorothy’s “Ullswater Excursion,” for all its frankness, actually seems reticent. Most of its emotional iceberg remains underwater. Then again, Dorothy apparently had no need to explain such personal contexts to her first readers. Perhaps an implicit understanding of circumstances was part of what she had in mind when she wrote to Lady Beaumont on 29 November, “To make [our daily goings-on and my own peculiar feelings] interesting love must be in your heart.”

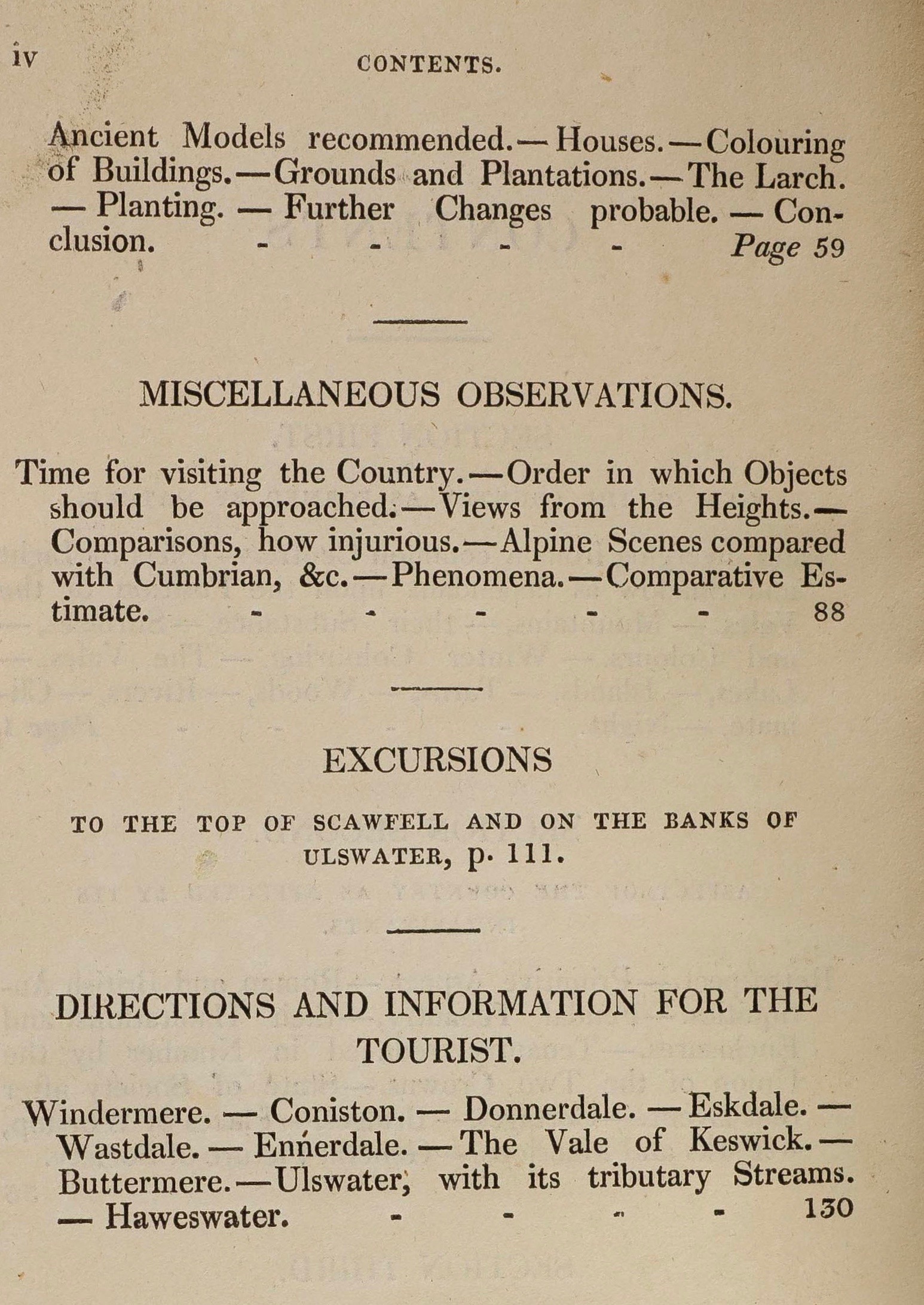

Because Dorothy’s original readers (in manuscript) must have been relatively few, the reception of the Ullswater text becomes easier to follow once it finds its way into print. Both of Dorothy’s “excursions”— “Excursion up Scawfell Pike” (1818) and “Excursion on the Banks of Ullswater” (1805)—have been widely admired since they first appeared, respectively, in the third (1822) and fourth (1823) editions of William’s Guide to the Lakes. Though written some 13 years apart, these texts were forever linked by being placed alongside each other (and similarly transformed) in all editions or reprintings of the Guide from 1823 forward (see fig. 3.2).

Figure 2. Table of contents for William Wordsworth’s Description of the Scenery of the Lakes in the North of England, 4th ed. (London: Longman, 1823), highlighting the climactic “Excursions” section. This new division, based on material written by Dorothy Wordsworth, provides the de facto conclusion of the book, followed only by the brief and utilitarian Directions and Information for the Tourist. (Courtesy: Brigham Young University, Harold B. Lee Library)

Whether quoting from them or reproducing them in full, Victorian travel books consistently attributed both excursions to William, largely as a result of his never publicly acknowledging Dorothy’s authorship.

At the 1883 gathering of the Wordsworth Society, Stopford Brooke attempted to support his argument about William’s propensity for “falling into the modes of poetry [even] in the midst of his prose” by quoting several remarkable passages from the Guide actually written by Dorothy.

This pattern of misattribution continued through the 1988 Penguin Classics edition of William’s Selected Prose, where these excursions were once again anthologized as by the famous poet rather than his sister.

B. Occasion of Dorothy’s Narrative

On one level, the Wordsworth siblings’ journey to Ullswater was a house-hunting trip. Fond as they were of Dove Cottage, it was becoming too small for the growing family and its regular house guests, especially in the wintertime, when everyone spent more time indoors. In November 1805, William and Mary had two children under the age of three and were expecting their third.

Moreover, they longed to become homeowners, as evidenced in numerous letters from this period contemplating possible locations and building projects. An early highlight of the trip to Ullswater, then, was inspecting Broad How, an attractive lot for sale near the Luffs’ home in Patterdale. Almost immediately, as Dorothy’s account chronicles, they began imagining a dream home there, and to that end William visited their friend Thomas Wilkinson to ask for help negotiating the purchase of this property.

Ultimately, with the help of Lord Lowther, William did purchase it in 1806. He held on to this plot for nearly 30 years but never did remodel the old home that stood there or build a new one.

To alleviate the crowding problem in Grasmere, the Wordsworths spent the winter of 1806–1807 at Coleorton as guests of the Beaumonts, and in 1808 they moved from Dove Cottage to Allan Bank.

“Ullswater Excursion” also records the Wordsworths taking strength from their extended network of friends and family, including the Hutchinsons at Park House and Captain John Wordsworth at Brougham Hall. (Captain Wordsworth was the kinsman who mentored their late brother in his sailor’s trade.) Yet, while never concealing that their trip was as much about domestic affairs and business as pleasure, Dorothy used the material at hand to create a first-rate piece of travel writing. She was fond of Ullswater because, as she told Lady Beaumont, it had not yet been spoiled by “fancy builders” and was “full of visions of things . . . that might have employed our fancy happily for hours, if they had not in the next moment been replaced by others as beautiful.”

And, like many of the age’s best travel narratives, Dorothy’s recounts experiencing a distinctive region chiefly on foot. Nature walks were of course among the Wordsworth siblings’ favorite pastimes, and, true to form, Dorothy managed to cover some 75 miles in six days, with only occasional breaks riding her pony (a recent gift from her oldest brother, Richard) or cruising in the Luffs’ rowboat. As Dorothy would afterward quip, her stamina left both herself and her brother “boast[ing] of [her] wonderful strength.”

If anything, Dorothy’s delight in the journey increased as it became more ambitious. Though confessedly reluctant to embark from Grasmere on a “damp and gloomy morning,” she reported that “as the mists thickened” over Kirkstone Pass, “[their] enjoyments increased.” On subsequent days—usually with William and sometimes also with their friends—she explored the lake’s southeastern shore, hiked over the mountains from Martindale to Patterdale, wandered through the Lowther Woods and the familiar streets of Penrith, and twice trekked the full length of Ullswater. On the final day alone, she and William walked or rode approximately 23 miles, all after 3:00 p.m. After coming back across Kirkstone by starlight, she and William arrived at Dove Cottage long after Mary and the children had gone to bed.

For Dorothy, this had been a genuine holiday, one reminiscent of tramps undertaken in earlier years, when she and her brother spent much of their lives walking, talking, and planning the future together. It must also have sparked memories of previous Ullswater visits, including their famed encounter with the daffodils beside the lake in 1802, when William was settling his affairs with Annette Vallon and preparing to wed Mary Hutchinson. Grounded, then, in feelings both present and past, “Ullswater Excursion” offers some of Dorothy’s most luminous writing. Over two centuries later, it still lingers in the ear and on the mind’s eye: “At such a time and in such a place every scattered stone the size of one’s head becomes a companion”; “Place-Fell steady and bold as a lion; the whole lake driving onward like a great river”; “We observed the lemon-coloured leaves of the birches . . . as the wind turned them to the sun, sparkle, or rather flash, like diamonds”; “The stars in succession took their stations on the mountain-tops”; “All the cheerfulness of the scene was in the sky.” These passages and others like them await the reader of “Excursion on the Banks of Ullswater,” which this edition presents with thorough annotations and illustrations.

A. Manuscripts

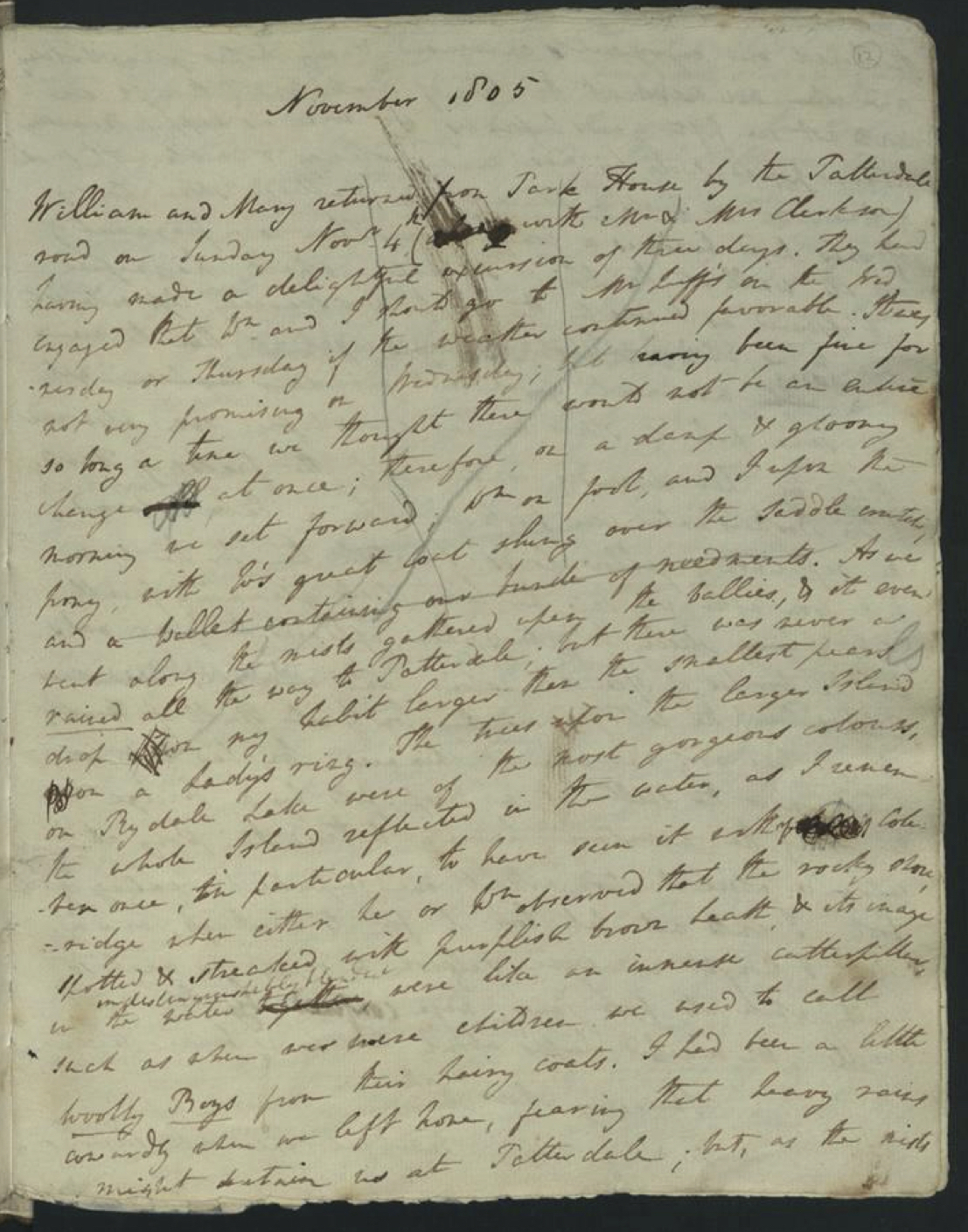

As noted previously, “Excursion on the Banks of Ullswater” survives in two manuscripts. The first, Dove Cottage Manuscript 51 (DCMS 51) is a hand-sewn notebook containing both prose and verse (fig. 3.3). This notebook preserves various materials related to the Ullswater text, including five pages of draft fragments (pp. 1–5) plus two experimental introductions (pp. 18–20) that helped produce the 1823 Guide to the Lakes. Its complete copy of the Ullswater narrative (pp. 21–34) is the earliest known. Like “Excursion up Scawfell Pike,” it shows multiple sets of revisions, some in pen and some (later) in pencil. The base layer is in Dorothy’s hand, while edits appear in her handwriting but possibly also in William’s. We ignore the penciled edits in our apparatus, seeking so far as possible to emphasize Dorothy’s own work rather than trace the evolution of William’s Guide. Still, all of the edits, along with the separate fragments and draft introductions, are arguably important for the reception history of Dorothy’s writing, and readers can see the results of the multistage revision process in our transcription of the 1823 Guide text.

Figure 3. First page of the complete Ullswater Excursion in DCMS 51. (Courtesy: The Wordsworth Trust)

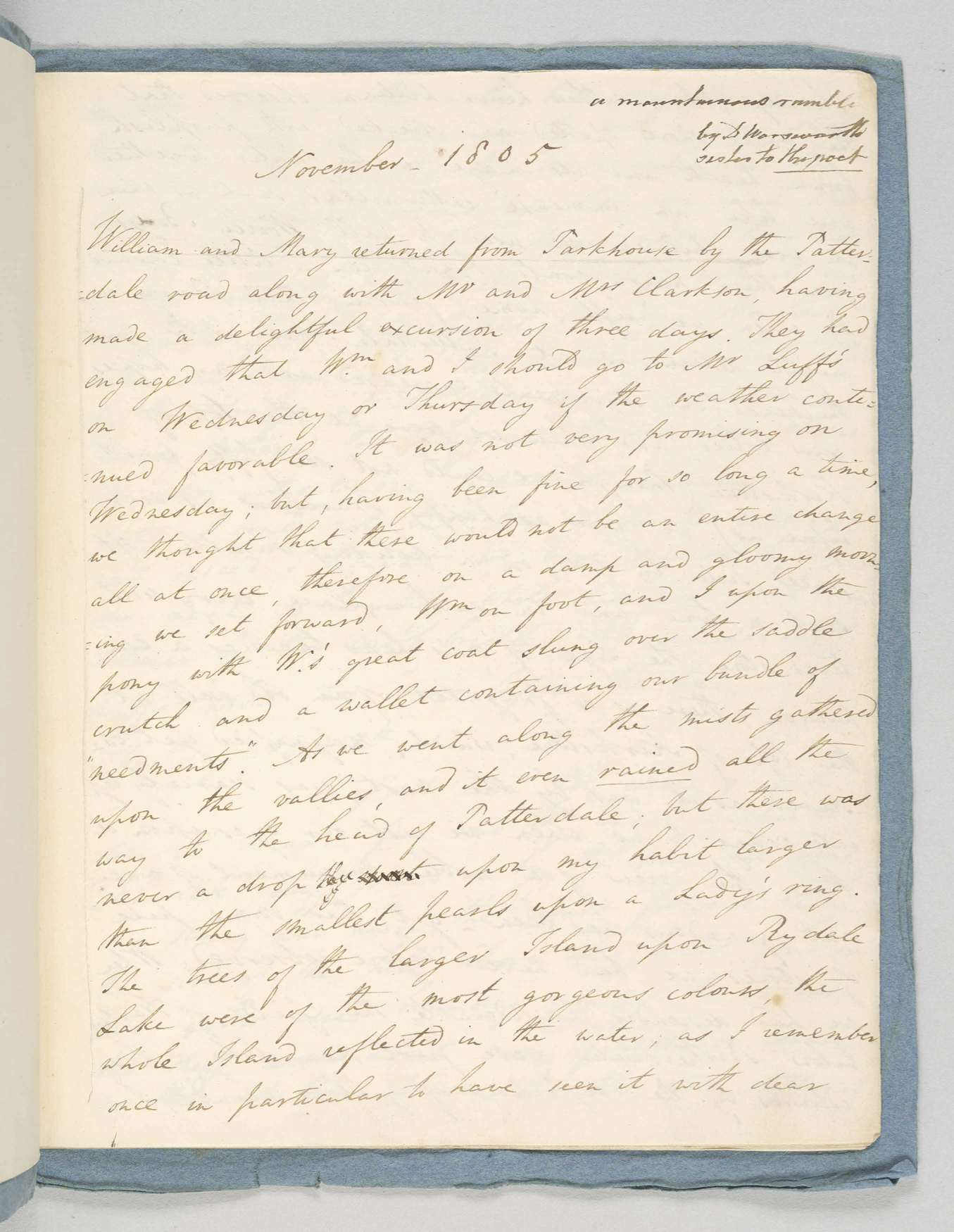

The second manuscript—the basis for our annotated text—played no direct part in the evolution of Wordsworth’s Guide. Now held by the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, this 16-page document (MA 1581) appears in Dorothy’s neatest hand (fig. 3.4).

Editors Owen and Smyser named it the “Coleorton Manuscript,” noting that it appeared among the Morgan Library’s “Coleorton Papers”

and supposing (with De Sélincourt) that it was made for Lady Beaumont, who for much of her life resided at Coleorton Hall in Leicestershire. Added support for their surmise comes from the manuscript itself, which features, at the top of its first page, a descriptive note in another hand: “a mountainous ramble by D Wordsworth sister to the poet.” While it is difficult to draw certain conclusions based on a 10-word sample, this appears to be the handwriting of Lady Beaumont.

In this attractive document, Dorothy edits the DCMS 51 text or a closely related draft for style and accuracy. Notably, she removes her account (from 11 November, day 6) of walking in Penrith at night, seeing old acquaintances, and revisiting familiar haunts. Perhaps she considered this tour of sites linked to her adolescence too private or just uninteresting for her likely readers.

In any case, the Coleorton Manuscript probably best reflects her intentions for a manuscript text to be read outside of the immediate family circle.

Figure 4. First page of the Coleorton Manuscript. (Courtesy: The Morgan Library and Museum)

B. Dorothy’s Account vs. William’s Guide to the Lakes

In William’s Guide, “Ullswater Excursion” gains acceptability for a general audience but loses some of its personality. As De Sélincourt succinctly puts it, “Dorothy wrote a journal of this tour which her brother afterwards recast and appended to his Guide to the Lakes: few readers will prefer his more formal, ‘literary’ version to Dorothy’s.”

To be fair, the Guide version is also memorable, adapted for its purpose and embellished with a few novel passages. Nonetheless, Dorothy’s original is warmer, more detailed, and generally more engaging. This is true not only because of what De Sélincourt calls her “vivid beauty of feeling and expression”

—most of her best descriptive passages do appear in the Guide, even if slightly altered—but also because of the intimacy of her report, which lends it human interest that might actually be out of place in a guidebook.

As in the case of “Excursion Up Scawfell Pike,” the first thing one notices in comparing Dorothy’s manuscript text to the Guide’s adaptation is that the latter is shorter and less personal. All of the individuals are missing: no “dear Coleridge,” no Luffs, no Hutchinsons, no Thomas Wilkinson. Even the pony is gone, and that seems a shame; the poor beast is an important character, if only for what he reveals about Dorothy, whose sympathy toward animals, both wild and domesticated, comes through strongly in the manuscripts.

Overall, then, the social nature of this tour becomes obscured in William’s retelling.

To be sure, William often adopts the first-person plural, as in “We left Grasmere vale,” “We noticed, as we passed,” and “The mists gathered as we went along”—his narrator does not wander lonely as a cloud. Nonetheless, his “we” remain basically anonymous. His formal “We were more than contented, ” describing the travelers’ wet crossing of the Kirkstone Pass, is far less evocative than Dorothy’s report of brother and sister cheerfully advancing through the mist, “as happy Travellers as ever paced side by side on a holiday ramble.” Lamentably, the changes made for the Guide, necessary as they might be to preserve privacy, tend to obscure the core relationship that drives the text: the partnership of the siblings, who must hold even more tightly to each other now that brother John is gone and the “set is . . . broken.”

That close partnership helps explain a blunt fact that frequently troubles today’s readers: William published a substantial work by his sister without acknowledging the fact. Even devoted Victorian Wordsworthians could find this appropriation odd, as did Knight in his 1889 biography of the poet: “[Wordsworth] concluded [the Guide] by incorporating the whole, or nearly the whole, of his sister’s journal, without any indication to the reader of who the real journalist was, or when his work ended, and that of his sister began!”

We feel certain that William did so with her cooperation; “Wordsworth” was the family brand, and Dorothy regularly did what she could to support it, contributing to her own financial security as well as her brother’s reputation.

The result was a substantially coauthored Guide to the Lakes, even if it was not publicly acknowledged as such. With her intimate knowledge of the region, her capacity for wonder, and her gift for descriptive language, Dorothy contributed significantly to the Guide’s success. As Mary Ellen Bellanca properly observes, “These considerations make plain that it is well past time to discard the notion of Dorothy Wordsworth as an unpublished, or only posthumously published, writer.”

That said, to the extent that we base our edited text on manuscript evidence, the posthumously published Dorothy Wordsworth takes precedence in this edition. We offer “Ullswater Excursion” complete with all of its personal, chatty, quotidian, and whimsical elements. By doing so, we privilege Dorothy’s perspective on the Lake District, acknowledge the terms of her appeal to her first readers, and celebrate the qualities that make her travel writing unique.

C. Published Versions

After William’s Guide to the Lakes, the first significant printing of Dorothy’s “Ullswater Excursion” appeared in the 1883 issue of the Transactions of the Wordsworth Society.

At that year’s gathering of the Society, William Knight announced that a copy of “a Mountain Ramble with the Poet, written by his Sister, in the year 1805” had come into his possession.

Though he lacked the requisite time to share the text at the meeting, he included an abridged version of it in the Transactions, explaining that “a curious recast of this Journal-record of his sister was published by Wordsworth in an edition of his Guide to the Lakes.”

Knight’s was the first publication of the narrative under Dorothy’s name, approximately 78 years after its composition.

Knight mentioned the text again in his 1889 biography of William, noting the poet’s incorporation of this “Mountain Ramble” in the Guide and calling it “one of the most curious instances of the literary ‘communism’ between [the siblings].”

Then, in 1897, he included his abridgment in his landmark edition of the Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth as “Journal of a Mountain Ramble by Dorothy and William Wordsworth, November 7th to 13th, 1805.”

Note that Knight’s consistent use of the word ramble suggests that he had discovered the Coleorton Manuscript, which includes that label on its first page (see fig. 3.3).

Knight’s edition remained the established text until 1941, when De Sélincourt included a new version in his own Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth.

He explained, “Professor Knight printed an abbreviated version, [but it] is here given complete from Dorothy’s manuscript.”

In fact, however, De Sélincourt sometimes followed Knight’s text, even while seeming unaware of the Coleorton Manuscript. It is possible that De Sélincourt worked from a third manuscript, now unknown,

but it seems more likely that he drew on DCMS 51 with an eye toward Knight. Instead of retaining Knight’s title (“A Mountain Ramble”), he privileged that used in the Guide to the Lakes, “Excursion on the Banks of Ullswater,” solidifying for twentieth-century readers the formal title we also adopt.

In 1974, Jane Worthington Smyser and W. J. B. Owen undertook the most thorough textual analysis to date of “Ullswater Excursion” in their Prose Works of William Wordsworth volume 2, Appendix IV, pp. 368–78). They detailed all available manuscript material, including the fragments and false-start introductions of DCMS 51, endeavoring to illuminate the textual history of William’s Guide. For tracing textual variants, their work remains indispensable. Unfortunately, Prose Works is available only at high cost or in research libraries. Our electronic edition incorporates many of its findings while adding fresh research, providing manuscript facsimiles and other illustrations, and placing Dorothy Wordsworth in the foreground for a broad audience.

D. Editorial Principles

As noted previously, this edition includes an annotated and illustrated text plus transcriptions of the two surviving manuscripts and the 1823 Guide text, allowing readers to compare. The annotated text is based on the Coleorton Manuscript, but we supply key omitted passages, known from DCMS 51, in the notes. We retain Dorothy’s idiosyncratic spelling and punctuation; therefore, readers should be aware that several place names differ from those found on modern maps (e.g., “Boar Dale” for “Boredale,” “Emont” for “Eamont,” “Glenriddin” for “Glenridding,” “Gowborough” for “Gowbarrow,” “Sanwick” for “Sandwick,” and “Yanworth” for “Yanwath” ). For clarity, we expand abbreviated names—“Wm” to “William,” “Sara H.” to “Sara Hutchinson,” “T. Wilkinson” to “Thomas Wilkinson”—and regularize “Mr.” and “Mrs.” in US style, adding a period and using no superscripts.